Kartu Prakerja is a pioneer of multi-channel and recipient-centric Government-to-Person (G2P) payment in Indonesia, proven to have built economic resilience and driven financial inclusion. The conventional G2P method has encountered several limitations such as insufficient coverage, high complexity, high operational cost, low transparency and accountability, and limited options for the recipients. The Covid-19 pandemic has escalated the urgency to serve people with a high-speed, large-scale, and reliable delivery system. The lessons learned from the design and implementation of Kartu Prakerja’s multi-channel G2P payment can be replicated by other programs to transform social protection.

Challenge

Insufficient coverage of social assistance delivery is the recurring issue with single-channel Government-to-Person payment. The conventional G2P method assigns only one Payment Service Provider (PSP) to serve a large number of recipients. Most single-channel G2P payments deliver cash transfers through bank accounts—which obliges recipients to open a bank account—or post offices. However, government-assigned banks and post offices are not invariably available in all regions. A survey by the National Financial Inclusion Council (DNKI) (2019) shows only 56 percent of Indonesian adults have a bank account, 20 percent live more than 5 km away from a bank, and 5 percent are not aware of the bank’s location. Meanwhile, Pos Indonesia only covers 42 percent of sub-districts or villages nationwide. Thus, the conventional approaches cannot serve extensive recipients nor ensure inclusion with such limited access.

Opening bank accounts and delivering cash assistance via post offices incur complexities and costs. In opening bank accounts PSPs need to collect the recipients’ personal information, assist with password configuration, and distribute passbooks; these cause complexities. PSP’s revenue from disbursing social assistance is below the cost of a bank teller transaction (Joyce et al., 2015). Allocating additional expenses and human resources is inevitable, leading to limited interest and investment in providing adequate service for single-channel G2P payment.

Some of the social assistance benefits may not be fully utilized by the recipients due to high costs and low transparency. The existing intermediaries may also claim fees out of the fund, leading to poor optimization. Time, travel, and opportunity costs also reduce social assistance’s net value, particularly in remote areas (Joyce et al., 2015). Banks and post offices are not open long enough to completely serve the queue. Multiple visits to the bank are required for recipients to complete the paperwork and collect payment. Data discrepancies might also reduce accuracy targeted recipients. Moreover, recipients have to manually check to the bank to find out whether they have received the fund.

Inconveniences in using the only assigned PSP available have led to low financial deepening. The conventional G2P is perceived to be costly, thus discouraging the acceleration of financial inclusion. The single-channel G2P recipients hardly use their bank accounts other than receive aid money. They tend to withdraw all the funds and leave their accounts dormant afterward (TNP2K, 2013). Therefore, it is essential to provide alternative payment methods to improve the recipients’ experience and encourage sustainable usage of the preferred PSP accounts.

The Covid-19 pandemic also drives the urgency to provide a fast, massive, and accurate social assistance disbursement. It requires changes related to data collection and the utilization of digital technology. A new way of G2P payment is necessary to adapt to people’s needs while preventing the spread of Covid-19. Kartu Prakerja has managed to implement multi-channel G2P by providing various channels of distribution, generating overwhelmingly positive responses as millions of recipients across Indonesia link their bank accounts or e-wallets to receive their incentives.

Proposal

We recommend a shift in the government program to multi-channel G2P payment to generate solutions for the challenges in conventional G2P payment. Kartu Prakerja’s multi-channel G2P payment has proven to drive financial inclusion and economic resilience for its recipients. In this section, we will demonstrate Kartu Prakerja’s incentive disbursement mechanism, how it could be replicated by other programs, its advantages and challenges, and its relevance to other countries and the G20 Meeting.

1. An Overview of Kartu Prakerja’s Multi-channel G2P Payment

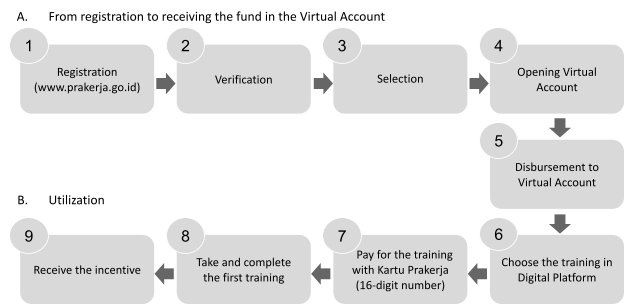

Kartu Prakerja is the first Indonesian government program that combines vocational training and cash transfer with an end-to-end digital implementation.[1] This program aims to improve labor force competency, productivity, competitiveness, and entrepreneurship skills. As the pandemic swept the country, the Government of Indonesia has pushed the program to maintain purchasing power and become a part of social assistance. Until 2021, 11.4 million people have received post-training incentives through the first implementation of multi-channel G2P payment in Indonesia. Every step of the user journey is digitally recorded in real-time, ensuring transparency and precision. Figure 1 illustrates Kartu Prakerja’s user journey (see Appendix 1).

Figure 1. Recipients’ User Journey on Kartu Prakerja Website

Within two years of innovation, Kartu Prakerja has successfully served the incentive disbursement with speed and accuracy. For instance, Kartu Prakerja incorporates Public-Private Partnership (PPP) with e-wallets alongside banks and provides choices of disbursement channels to the recipients. The Program Management Office (PMO) of Kartu Prakerja follows a recipient-centric approach and sets the recipient’s interests as the priority. Beyond the collaborations, Kartu Prakerja also set regulations for its payment partners or payment service providers (PSPs) regarding the account linkage, Know Your Customer (KYC) process, and disbursement (see Appendix 2). In addition, Kartu Prakerja built integrated systems with digital and cloud technology for extensive public service for incentive disbursement. The mechanism comprises at least three essential systems:

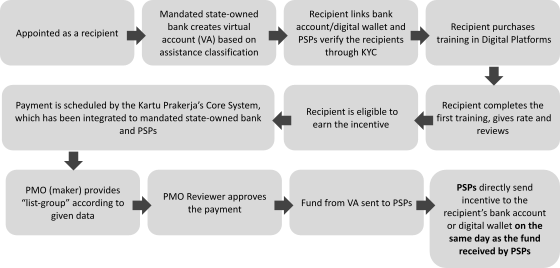

a. Kartu Prakerja’s Core System

Recipients must complete one training to be eligible for the post-training incentive. The core system, built by Kartu Prakerja engineers, collects information about training completion dates. The system will generate the incentive disbursement schedule for each recipient and a “list-group” based on the disbursement date.

b. Mandated State-owned Bank’s Direct System

A state-owned bank mandated to manage the government accounts for Kartu Prakerja has a role in transferring the funds to Kartu Prakerja’s PSPs. After the “list-group” generated from Kartu Prakerja’s core system is submitted to the bank’s system, the bank automatically debits the PMO’s account and credits the fund to the PSPs’ account

c. Payment Service Providers (PSPs) System

After PSPs receive the funds, they directly transfer the incentive to each recipient. The PMO monitors to ensure that PSPs comply with the service level agreement.

Figure 2. Kartu Prakerja’s Disbursement Scheme

Kartu Prakerja’s process optimizes the spending of the state budget. It will deactivate the recipients’ status and virtual account (VA) if they fail to utilize the training assistance within the designated period. All the funds will be returned to the government account and redirected to other applicants. In 2021, Kartu Prakerja acquired appreciation from the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Committee (KPK) as an exemplary government program that has implemented various best practices.

Lessons Learned from Kartu Prakerja’s Multi-channel G2P Payment

Kartu Prakerja is the first social assistance program in Indonesia that provides multiple disbursement options. According to the PMO’s Evaluation Survey (2021), 93 percent of the recipients agree this method is more suitable than cash disbursement. Here are some advantages incorporated into the program.

First, a multi-channel G2P enables large-scale incentive disbursement with high accuracy, speed, and transparency, which is highly relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic. Several approaches are implemented in the disbursement, including

- A bank/e-wallet account must be under the recipients’ name, guaranteeing the accuracy of target recipients.

- Incentive disbursement is traceable and digitally recorded; increasing accountability for both PSPs and PMO.

- The incentive can be received on the same day the recipient becomes eligible. The total disbursement, schedules, and payment status are available on Kartu Prakerja’s dashboard. Recipients also receive a full amount of incentive without reduction.

Second, through partnerships with some of the largest PSPs in Indonesia, Kartu Prakerja PMO and its partners share the same duties and risks when disbursing the incentive. By using an Application Programming Integration (API) system and KYC procedures, Kartu Prakerja has an integration credential of data exchange. KYC run by the PSPs also shows that the verification process is not only carried out by Kartu Prakerja, but also double-checked by PSPs. This practice provides an advantage to the program since PSPs’ mechanisms are able to detect fraud or other suspicious transactions, complementing Kartu Prakerja’s system.

Third, the program’s payment system provides various PSPs choices, allowing recipients to choose which account is most suitable for their needs. Options provide convenience, autonomy, and rights on how recipients access and utilize their incentives as well as engage in financial services. Bank accounts and e-wallets offer advantages that correspond to the diverse needs of recipients. The 2020-2021 Evaluation Survey shows why recently financially-included recipients prefer bank/e-wallet to receive their incentives. About 87 percent of recipients choose e-wallet for their incentive disbursement channel because they are easier to access via smartphone (47 percent); recipients live far from the bank (22 percent); and opening an e-wallet account does not require a first deposit (10 percent). Around 13 percent of recipients choose a bank account as their disbursement channel since it is perceived to be safer (38 percent); they have closer access to the nearest bank/ATM (37 percent); and they can ask the bank officer for assistance (6 percent).

Fourth, multi-channel G2P eliminates time and costs in single-channel G2P, resulting in recipients getting the most out of their benefits. Intermediary, transportation, time, and other fees, which usually arise when acquiring incentives, are cut down to the minimum since PSPs directly transfer the incentive to the chosen bank or e-wallet. The technology enables Kartu Prakerja to provide training and disburse incentives transparently without requiring personal mobilization during the Covid-19 pandemic. Notification on the dashboard reduces the time and costs of periodically checking the bank account and helps notify recipients when the incentive is received. Recipients possibly cash out their incentives at the nearest access points in their preferred time. Forty-three percent of recipients cash out on the same day as they receive the incentives, and only 5 percent do it after seven days (Evaluation Survey, 2021).

Fifth, multi-channel G2P accelerates financial inclusion and encourages financial deepening. Kartu Prakerja enables financial inclusion for 27 percent of recipients who previously did not have a bank or e-wallet account before joining the program. Around 87 percent of the recently financially-included chose e-wallet as their disbursement channel.

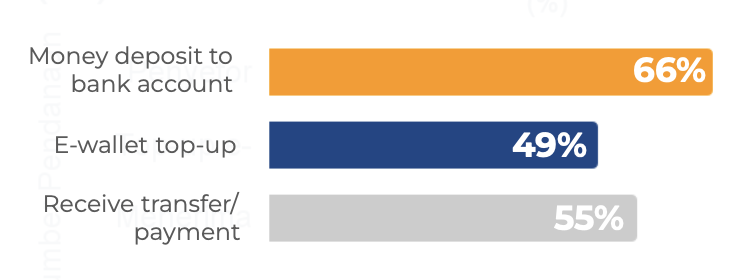

The recently financially-included recipients also experience financial deepening. As much as 29 percent of the recently financially-included recipients use their accounts for personal and business needs. Figure 3 in the following shows financial activities for the general recipients and those who are recently financially-included. Both groups use their own money for further usage of their bank account/e-wallet which activities include: bank account deposit (49 percent), e-wallet top-up (33 percent), and receiving transfers or payments from other people (42 percent). Alatas et al. (2021) evaluated the impact of Kartu Prakerja and found financial deepening of the program recipients, which aligns with the Evaluation Survey’s results. Kartu Prakerja promotes financial inclusion with an increase in e-wallet penetration by 53 percent. Moreover, recipients are 40 percent more likely to purchase online using an e-wallet compared to non-recipients.

Recently financially-included recipients

Recipients in general

Figure 3. Financial Activities for Kartu Prakerja’s Recipients

Lastly, an efficient and swift disbursement through multi-channel G2P has proven to assist people not falling into poverty and drive economic resilience. Kartu Prakerja incentive is used for maintaining recipients’ purchasing power. TNP2K and World Bank’s study (2022) found that 69 percent of recipients cashed out the entire incentive, while 31 percent only partially or not at all. Around 43 percent of recipients withdrew their incentives on the same day they received the fund (Evaluation Survey, 2021), while 85 percent only needed 15 minutes or less to cash out their incentives (TNP2K and World Bank, 2022). The incentive withdrawal is utilized to accommodate their basic needs, while monthly incentive contributes to 61 percent of the average household’s food expenses (Evaluation Survey, 2021). Furthermore, Kartu Prakerja helps recipients become entrepreneurs through post-training incentives. As many as 84 percent of recipients stated that they have used their incentives as business capital. Of that figure, 79 percent spent on production materials (Evaluation Survey, 2021).

Challenges of Kartu Prakerja’s Multi-channel G2P Payment

Despite numerous advantages of implementing multi-channel G2P payment, we also encountered some obstacles which include:

- A new and unfamiliar method to people

Although 96.8 percent of recipients could link the bank/e-wallet account, some of them still reported difficulties in linking the account (World Bank, 2022). Of those who failed this step, the majority did not understand the new methods to link their accounts. Recipients also have less understanding of the program context, digital and financial literacy, and access to mobile phones and the internet.

- Limited coverage only to those who can be financially included

The Global Financial Index (World Bank, 2022) indicates that a moderately low percentage of adults are financially literate in Indonesia (51.76 percent). Trust and habit are the main factors behind the usage of financial services. As recipients are required to open a new account or activate it themselves and link it into Kartu Prakerja’s system, some recipients have no access to the banking system.

- The KYC system often hinders the disbursement

KYC is mandatory to ensure the incentive is transferred to the right recipients. The top 5 inquiries and complaints include failure to upgrade and in account linkage, which requires KYC. This results in failure of receiving the incentives.

- Some skeptical views of the new method

Kartu Prakerja’s social media interactions and reports by partners point out that recipients persistently ask when they will receive the incentives despite having all relevant information on their dashboard. This shows that recipients are still skeptical about the incentive disbursement’s transparency.

- The disbursement requires systems to connect payments and PSPs collaboration

In practice, the government must establish an ecosystem regulating the flow of the disbursement system. This practice is challenging in terms of budget, human capital, and leverage of the existing infrastructure (e.g., not all PSPs have the capacity to complement Kartu Prakerja’s system).

Understanding the challenges, Kartu Prakerja continues to provide a wide range of solutions. To do so, the initiatives to move forward are as follows.

| Challenge | Proposed solution |

| A new and unfamiliar method to people | Understanding the program’s context and campaign for a variety of disbursements. The PMO presents a video guidance on linking the banks/wallets account and actively conducts socialization in collaboration with the PSPs Building a reliable contact center and burden-sharing with the PSPs for inquiries and complaints Implementing a recipient-centric mindset with continuous improvement of user interface and experience |

| Limited coverage only to those who can be financially included | Demonstrating socialization on-demand application and seeding new applicants possible to bankable Promote a more digital payment system and interoperability Incentivizing participation with post-training incentives that trigger people to participate in the program |

| The KYC system often hinders the disbursement | Informing the requirement to link bank/e-wallet account in Kartu Prakerja’s dashboard. For instance, ensure that recipients use the same identity and phone number in bank account/e-wallet and Kartu Prakerja’s system Providing notification of bank account or e-wallet linkage status on the dashboard |

| Some skeptical views of the new method doubt its transparency | Building public trust and security systems. Kartu Prakerja developed a user-friendly dashboard in which the system records all disbursement data and monitors the compliance to service level agreement to ensure that PSPs immediately transfer the incentive Guaranteeing data privacy and protection to ensure direct transfers to recipients’ accounts |

| Requires a system to connect payments, collaborate PSP System and government programs | Opening the system – every PSP can participate and compete, but still under regulation Enforcing the PSPs in leveraging innovations to improve their systems and services |

4. G20 and Other Countries Relevance

Kartu Prakerja’s incentive disbursement scheme is aligned with the digital transformation issues as the G20 priority. The multi-channel G2P payment of Kartu Prakerja is a prominent example of the government’s digital systems and processes in social assistance disbursement. With Kartu Prakerja’s success story, the collaboration system built by this program can be adopted by other social assistance. In addition to that, Kartu Prakerja spurs digital finance practices and knowledge that improve people’s literacy. The program design enforces people to learn how to use digital technology, creating a positive externality of end-to-end digital implementation.

Kartu Prakerja also complements G2P practices worldwide with its unique program design and interface. This program is not the only one implementing multi-channel G2P payment in the world. India has developed a direct benefit transfer platform that manages multiple schemes and links with the payment and ID systems, enabling seamless payment processing into customer-chosen accounts in 2016. Not long after, Tanzania also launched Tanzania’s Social Action Fund (TASAF), designing a multi-channel payment delivery system for social safety net payments. In 2017, Zambia’s Ministry of Social Affairs launched a pilot payment delivery system across multiple providers with customer choice. Bangladesh’s Access to Information (A2i), an e-government initiative, designed a plug-and-play e-payments system launched in late 2018. However, Kartu Prakerja may still be a role model as no program progressed as fast within three weeks of implementation. The program has also built its core system to manage the incentive disbursement, which is connected to the payment system of the mandated state-owned bank with no human operation.

Conclusion

The multi-channel G2P payment is successfully applied in Indonesia for the first time through Kartu Prakerja. As Covid-19 brought additional challenges in delivering assistance, Kartu Prakerja has effectively tackled the issues and disbursed funds in a fast, large-scale, and accurate way. This policy paper elaborates on how to construct various PSP options with its benefit. It has given the world’s countries a sign to shift their social assistance delivery to this method. Intergovernmental collaboration, private sector incorporation, and support to build integrated systems through digitalization between public services and financial services may still need further action.

References

Financial Services Authority, National Strategy for Financial Inclusion in Indonesia 2021 – 2025, Jakarta, December 2019, https://www.ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/publikasi/Pages/Strategi-Nasional-Literasi-Keuangan-Indonesia-2021-2025.aspx

Jenny C. Aker et al., “Payment Mechanisms and Antipoverty Programs: Evidence from a Mobile Money Cash Transfer Experiment in Niger”, in Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 65, No. 1 (October 2016), p. 1-37

Kartu Prakerja Program Management Office, Evaluation Survey Data 2020, Jakarta, December 2020

Kartu Prakerja Program Management Program, Evaluation Survey Data 2021, Jakarta, December 2021

Michael Joyce (eds), Qualitative Survey and Alternative G2P Payment Channels in Papua and Papua Barat, Jakarta, The National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction, 2015, p. 41-43 (TNP2K Working Paper 26-2015)

National Council of Financial Inclusion (DNKI), Financial Inclusion in Indonesia 2018, Jakarta, 2019, p. 7-12, https://snki.go.id/dnki-703-orang-dewasa-pernah-menggunakan-produk-atau-layanan-keuangan-formal-tetapi-hanya-557-orang-dewasa-memiliki-akun/

Statistics Indonesia, National Labor Force Survey Data August 2019, Jakarta, August 2019

Statistics Indonesia, National Labor Force Survey Data August 2021, Jakarta, August 2021

The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor, G2P 3.0 A Future For Government Payments, Washington, May 2018, p. 5-19, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/263411528847713133-0160022018/original/12.30pmMay08PensionsChenConceptandEarlyLearnings.pdf

The National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction (TNP2K), Social Assistance Disbursement through Bank Account, Jakarta, January 2013, p. 9, https://www.tnp2k.go.id/images/uploads/downloads/Design%20Study%20of%20PKH%20book%202%20versi%20indo_LB.pdf

Vivi Alatas (eds), Kartu Prakerja Impact Evaluation: Preliminary Findings, Jakarta, The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab South-east Asia, 2021, p. 2, https://public-prakerja.oss-ap-southeast-5.aliyuncs.com/www/ebook-reporting/Ringkasan_Eksekutif_Kajian_Evaluasi_Dampak_Kartu_Prakerja_2021_oleh_J-PAL_SEA_Bahasa_Inggris.pdf

World Bank and TNP2K, Kartu Prakerja: Indonesia’s Digital Transformation and Financial Inclusion Breakthrough, Jakarta, June 2022, https://youtu.be/ljY9IobzanI

World Bank, The Global Financial Inclusion Database 2021, June 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex#sec3

Appendix

- Kartu Prakerja’s user journey:

- With an on-demand application approach, applicants can directly register through the website. Information about batch opening, selection results, and how to join the training courses are all available in the dashboard.

- The verification process involves integrated data from the Director-General of Population and Civil Registration of the Ministry of Home Affairs (Dukcapil) and other relevant ministries/institutions. Kartu Prakerja ensures equality and accessibility for its applicants by not selecting applicants who have received other forms of social assistance and limiting the number of Kartu Prakerja recipients up to 2 family members in a household.

- The randomized selection generates the list of recipients. Applicants will receive the selection result via email, SMS, and a notification in their dashboard.

- Virtual accounts (VA) are activated to keep the training assistance and incentives. Next, each VA is linked to each recipient’s Kartu Prakerja number used to purchase training courses through the digital platforms. After the training completion, the recipients are expected to rate and review their training.

- The recipients will be eligible for a post-training incentive through their PSP account. After receiving the incentives, the recipients are then eligible to fill out three evaluation surveys.

- Kartu Prakerja set regulations for PSPs regarding:

- Linking bank account/e-wallet to Kartu Prakerja’s dashboard

- recipient accounts have to be verified through the e-KYC process or upgraded

- ID number, full name, and phone number registered for the account should match the forms registered with the Kartu Prakerja system.

- One ID number for one account.

- KYC process

- PSPs must verify recipients’ identity based on Dukcapil (checking on ID number and mother’s name at the minimum)

- PSPs must utilize the Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to scan the ID card and verify the information on the card

- PSPs must use the liveness technology that allows them to verify recipients’ faces (checking when they blink, open their mouths, and shake their heads at the minimum)

- PSPs must use the face recognition to verify recipients’ selfies while showing their ID card

- PSPs must have a fraud management system to ensure transaction security

- PSPs must allocate human resources to manage and be responsible for the e-KYC process

- Human resources for the e-KYC process must differ from the group assigned for managing the customer complaint

- PSPs must have a risk management mechanism

- Disbursement

- Incentives are classified as post-training incentive and survey incentive

- Once the fund is received from the mandated state-owned bank, PSPs must immediately transfer the incentive to recipient accounts

- PSPs must comply with the service level agreement

- PSPs must send back the fund to the mandated state-owned bank when they fail to transfer the incentive to the recipients before the designated time

- PSPs must dispose to improve their system if PMO requests an adjustment

- Linking bank account/e-wallet to Kartu Prakerja’s dashboard

- Kartu Prakerja’s assistance is classified as training assistant amounts to 1 million IDR, and the post-training incentive after the recipients accomplish training is 2.4 million IDR in total, disbursed within 4 months, respectively ↑