We propose to institute a new annual tax of 0.2% on corporations’ stock shares for all publicly listed companies headquartered in G20 countries. As the G20 stock market capitalization is around US$ 90 trillion, the tax would raise approximately US$ 180 billion each year. Because stock ownership is highly concentrated among the rich, this global tax would be progressive. The tax could be paid in-kind by corporations (by issuing new stock) so that the tax does not raise liquidity issues for new and innovative firms, nor does it affect business operations. The tax could be enforced by the securities commissions in each country, which already regulate publicly traded securities.

*Saez: University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, (e-mail: saez@econ.berkeley.edu). Zucman: University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, (e-mail: zucman@berkeley.edu). We thank Tito Boeri, Murray Leibbrandt, and Dennis Snower for helpful discussions and comments. We acknowledge funding from the Berkeley Center for Equitable Growth and the Berkeley Stone Center on Wealth and Income Inequality. This policy brief is based on the longer article Saez and Zucman (2021) forthcoming in Economic Policy.

Challenge

Large multinational companies have been the largest winners of globalization and yet can easily avoid paying corporate taxes by shifting profits to tax havens (e.g., Zucman 2014; Saez and Zucman 2019a; Tørsløv, Wier, and Zucman 2020). This fiscal injustice undermines support for our modern and open global economy. The pandemic has reinforced two of the defining trends of the pre-coronavirus global economy: the rise of business concentration and the upsurge of inequality. Therefore, it is urgent to reconcile globalization with tax justice, and to demonstrate practically that economic integration can go hand in hand with a greater taxation of those who most benefit from this process. The G20 is the ideal level to improve taxation of multinationals because this is easier to achieve through international cooperation and the vast majority of the largest multinationals are headquartered in G20 countries.

While there have been proposals to make the corporate tax system work better, they tend to be highly technical and require complex enforcement infrastructure. They are also hard for the public to understand. Here, we propose a much simpler solution that could resolve the challenge while gathering strong public support. In this policy brief, we propose to institute a new tax on corporations’ stock shares for all publicly listed companies headquartered in G20 countries. Each company would pay 0.2% of the value of its stock in taxes each year. The securities commissions in each G20 country (which already supervise the creation and transactions of equity securities) would be in charge of administering the new tax.

Because stock ownership is highly concentrated among the rich, a tax on the capitalization of listed companies would be highly progressive. As the G20 stock market capitalization is around US$ 90 trillion, or about 90% of the G20 countries’ GDP of US$ 100 trillion, the tax would raise approximately US$ 180 billion each year, approximately 0.18% of the GDP of the G20. This tax is akin to a wealth tax on the market value of corporations, so that the most successful companies pay the most. It would be easy to enforce and difficult to avoid, as publicly traded securities are already highly regulated by the securities commissions of each country. These regulators already charge various (but generally modest) fees on stock issuance and transactions.

Our proposal works best if the largest economies coordinate to adopt the tax jointly. Corporations headquartered in the G20 represent over 90% of global corporate equity market value. Therefore, the G20 would be the ideal institution to negotiate the creation of such a tax and decide how its proceeds should be allocated between member countries. A number of allocation keys can be considered: the proceeds could be allocated among G20 countries or globally (including to non-G20 countries), proportionally to population, to the amount of sales made in each country, to the value of the tangible capital stock, and to a combination of these (and other possible) factors. The tax could also be used to fund global public goods, to address global externalities (most importantly climate change), and to build an international global sovereign fund. Because the tax rate is low (only 0.2%) and G20 countries are in need of tax revenue due to the large increase in public debts due to the COVID crisis, it is conceivable that most or all G20 countries could agree to such a tax in the foreseeable future.

Proposal

A NOVEL WEALTH TAX ON CORPORATIONS’ STOCK VALUES

In the new tax we propose, the securities commission of each country (the agency in charge of regulating publicly traded stocks) would each year levy a tax equal to 0.2% of the market value of each publicly listed corporation at the end of the year. Each corporation could pay the tax in cash or in kind. Payment in kind means that corporations would have the option of paying the tax in the form of corporate shares that the securities commission would then resell on the market. With the option to pay in kind, even liquidity-constrained corporations could pay the tax without affecting their finances or direct business operations. The stakes of existing shareholders would simply be diluted by 0.2%.

The stock of publicly traded corporations is an asset class highly amenable to an easy-to-administer wealth tax, because corporate stock is divisible and trades on a market. The very notion of corporate shares is what makes it possible to diversify ownership and also what makes it possible for a government to levy a tax in kind in the form of shares that can immediately be resold for cash. This is in contrast to real estate property, which cannot be as easily divided. Real estate property taxes are ubiquitous for historical reasons, despite the fact that they raise substantial liquidity issues and hence are among the most disliked forms of taxation (Wong 2020). The inclusion of real estate property in the base of European wealth taxes is one of the reasons behind the demise of these taxes, as affluent but illiquid real estate owners could, in some instances, face hardship to pay the tax (Saez and Zucman 2019b). The wealth tax on corporations’ stock that we propose would not suffer from this issue.

Security commissions in each country, such as the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States, already control and regulate the listing, initial public offerings, additional stock issuance, and all transactions of corporate stock on the exchange. Security commissions already charge modest fees for most such activities.1 This implies that it would be very easy to administer and enforce the tax we are proposing within the existing institutional structure.

ECONOMIC EFFECTS

Rate of return on stocks. The tax would reduce the annual rate of return from owning listed corporate equity by 0.2 points. To put this tax in perspective, it is useful to remember that mutual funds charge fees based on asset values. These fees which are not dissimilar to a private tax averaged about 0.5 points in the United States in 2018 (Morningstar 2019), significantly more than the tax we propose.2 A 0.2% tax on the market value of listed equities would make this asset class slightly less attractive to savers relative to fixed-income assets (cash, savings accounts, and bonds), private businesses, and real estate. The tax would capitalize into equity prices, thus reducing the valuation of publicly traded corporate stock relative to other asset classes. For example, in a standard asset pricing model, if the discount rate is 4% per year, a 0.2 percentage point tax in perpetuity reduces the value of an infinitely-lived asset by 0.2 / 4 = 5%. The drop in stock value would hit owners at the time the tax is enacted. Thus, the current owners of existing listed corporations who have tended to fare well during the COVID-19 pandemic would initially bear the burden of this new tax.

Incentives to become publicly listed. The tax would also create an extra cost to becoming a publicly traded corporation, as opposed to remaining private. To counterbalance this distortion, it would be desirable to impose an equivalent tax on the largest private businesses. Large private businesses are also organized indivisible shares and generally have multiple shareholders. Any private business whose share value exceeds, say, US$ 1 billion could be charged a tax corresponding to 0.2% of its value, like for listed companies.

Administering a tax on unlisted companies does not raise insuperable difficulties. First, governments typically collect extensive information on large private businesses for the purpose of administering the corporate income tax, including detailed income statements and generally balance sheets. This information makes it possible for tax authorities to identify large private companies that have a market valuation that is likely to be in excess of US$ 1 billion.

Second, like in the case of public companies, the tax could be made payable in shares that the government could resell, effectively creating the market that currently is missing (Saez and Zucman 2019b). This would ensure that large credit-constrained companies are still able to pay the tax. Private companies could also be given the option to let the government become a notional shareholder (taking a 0.2% extra notional stake each year) and redeem its notional stake upon sale of the business or at the time the business becomes public.

Complementarity with corporate profits tax. In principle, stock market values reflect both the value of the assets owned by the corporation (such as land, buildings, capital equipment, intangibles, and financial assets net of debts) and the future stream of profits that the business is expected to generate. The stock market value is thus not perfectly correlated with current profits, which are the base for existing corporate income taxes. In today’s globalized and fast-moving world, companies can become enormously valuable once they establish market power, even before they start making significant profits. Amazon and Tesla are two recent and striking examples. The wealth tax would make such companies (and hence their fortunate shareholders) start paying taxes sooner. A wealth tax on corporations is a useful tool to make billionaires (and other wealthy shareholders) pay taxes in proportion to their ability to pay and in line with the enormous accumulation of wealth generated by the new global corporate behemoths.

Would there be a risk of double taxation by imposing both a corporate profits tax and a corporate wealth tax? Because corporate taxes have fallen dramatically in recent decades (e.g., Zucman 2014) and the proposed wealth tax is modest, we are far from a situation where double taxation may be considered an issue. However, if the wealth tax succeeds and its rate is increased (for example to 1%), it would become possible to explore ways to alleviate double taxation. For example, the wealth tax could become a minimum tax that kicks in only if regular profit taxes are below the wealth tax liability. Effectively any wealth tax paid could become a non-refundable tax credit against the corporate profits tax.

Business operations. Because the tax can be paid in kind by issuing new stock, the tax has no direct impact on cash flows. Thus, it would not directly and negatively affect credit-constrained companies. Listed firms always have the option to issue new stock, although struggling firms may not be able to raise much if their stock price is already low. But because the tax is set as a fixed fraction of shares (0.2% in our proposal), the burden for struggling firms with low stock value is modest. Issuing only 0.2% of new shares should have only minimal impact on the stock price given existing volumes of transactions.

REVENUE AND PROGRESSIVITY

Revenue. The revenues generated by the tax we describe depend on the capitalization of the stock market of G20 countries, and how the tax would affect this capitalization. To simplify the exposition, we focus on mechanical revenues applying the 0.2% tax to current stock market capitalizations. As the computation above illustrates, a simple way to factor in behavioral responses is to reduce capitalization (and thus revenues) by 5%.

To start the analysis, it is useful to focus first on the case of the United States which has the largest stock market capitalization in the world and to put market capitalization in the more general context of the evolution of private wealth.

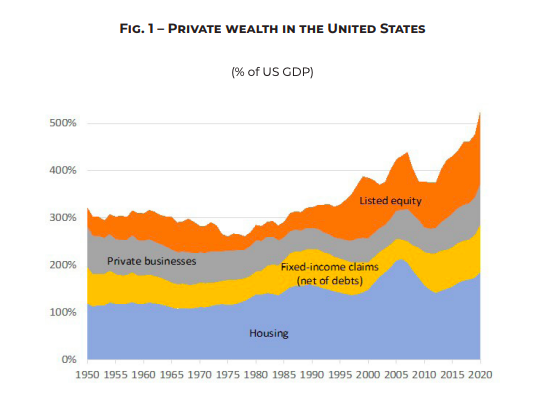

Figure 1 shows the evolution of total private wealth in the United States, expressed as a fraction of GDP. Private wealth is the sum of the wealth of households and the wealth of non-profit institutions serving households. A number of striking patterns are worth noting. First, total private wealth has doubled relative to annual output since 1975. The private wealth to GDP ratio has increased from about 260% in 1975 to close to 530% in 2020. At a basic level, this means that taxing wealth can generate a large and growing amount of revenue relative to the annual flow of income and output. Second, the main driver of this rise has been the increase in the value of listed corporate equities (including equities held indirectly through pension funds). Listed equities have increased from about 30% of GDP in 1975 to more than 150% of GDP in 2020. This asset class alone accounts for almost half of the rise of the private-wealth-to-GDP ratio in the United States. Third, listed equity wealth has increased particularly fast relative to GDP during the coronavirus pandemic, both due to a rise in stock prices and a decline in output. Last, and as a result of this trend, listed equities now account for about 30% of the wealth of US households and non-profits, second only to gross housing wealth (35%).

Since listed equities owned by households and non-profits add up to about 150% of GDP today, the tax we propose would generate at least 0.3% of US GDP in annual revenue (0.2% times 150%). In practice the US equity market capitalization is slightly higher than 150% of GDP, because of intercorporate holdings of listed equities. These equities would be subject to the tax at source, in effect causing a small double tax. In addition, US households own equities in foreign corporations, and foreign investors own part of US listed equities. However, such cross-border equity holdings (to the extent that they involve G20 countries) do not affect revenue from the perspective of the G20 as a whole (but simply which G20 country would collect the revenues). In the case of the United States, net cross-border holdings of listed equities are close to zero (in 2019, foreign portfolio equities owned by the United States were about as large as US portfolio equities owned by non-residents). This means that the revenues that would actually be collected by the SEC would be close to 0.3% of US GDP (about US$ 60 billion).

If we now generalize these computations to the G20 as a whole, based on World Federation of Exchanges data, we estimate that the G20 stock market capitalization was around US$ 90 trillion in 2019 (about 90% of the G20 countries’ GDP of US$ 100 trillion).3 Thus the tax would have raised approximately US$ 180 billion that year, close to 0.2% of the GDP of the G20. This is a bit less than what we estimate for the United States (0.3% of US GDP) because stock market capitalization is higher than average in the United States: 150% of GDP in the United States vs. around 120% in Japan, 85% in France, and 55% in Germany. Revenues would range from around 0.1% of GDP in a country like Germany to 0.3% of GDP in the United States averaging to about 0.2% of GDP for the G20 as a whole.

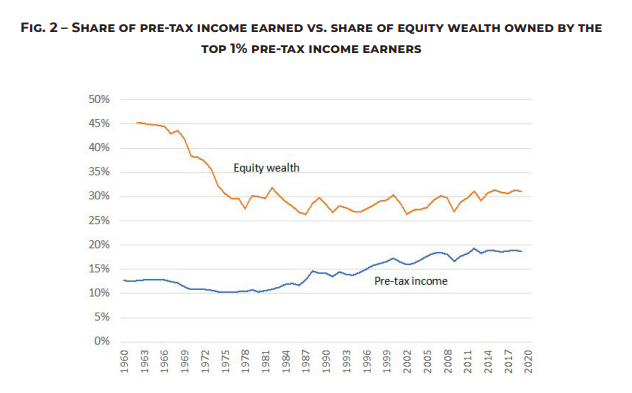

Progressivity. Because stock ownership is highly concentrated among the rich, this global tax would be progressive. To quantify this aspect, Figure 2 focuses on the case of the United States, a country where detailed estimates of the joint distribution of income and equity wealth (including held through pension funds) are available, from the distributional national accounts micro-files of Piketty, Saez and Zucman (2018).

According to these estimates, the top 1% of adults with the highest pre-tax income earned 19% of total pre-tax national income in 2019. They also owned about 30% of all listed equity wealth. Therefore, even a flat tax on listed equity wealth would be progressive. Such a tax would also increase the progressivity of the US tax system, since the top 1% currently pays about 21% of all (federal, plus state and local) taxes in the United States. That is, the current effective tax rate of the top 1% (all taxes included) is only barely higher than the average US tax rate, hence the share of taxes paid by the top 1% (21%) is barely higher than the share of pre-tax income earned by the top 1% (19%) both of which are significantly lower than the share of our new tax that would be paid by the top 1% (about 30%). In other countries where a lower fraction of equity wealth is owned through pension funds, the tax could be even more progressive (similar to the US situation in the 1960s and 1970s, before the rise of pension funds see Figure 2).

HOW COULD G20 COUNTRIES AGREE TO SUCH A TAX?

International agreement. The best way to implement such a tax would be through an international agreement whereby all countries in the G20 would agree to create it simultaneously. Each country would collect taxes on its own companies. Companies listed in multiple stock exchanges (a common occurrence among large multinationals) would be taxed only once. The advantage of an international agreement is that listed companies have no way to escape the tax as they need to be listed somewhere. Even if a tax haven stock exchange develops, as such companies do a large fraction of their business and sales in G20 countries, it is possible for the G20 to impose remedial taxes on companies listed in tax havens. For example, the G20 could require any such company to report the fraction of its global sales made in G20 countries and require a pro-rated payment of the wealth tax. If the company makes 80% of its sales in the G20, it would have to pay a wealth tax of 80% x 0.2% = 0.16% of its stock value.

The simplest way to allocate the proceeds of the tax is for each country to collect taxes on companies listed on its own stock exchanges. For multinational companies, it would make sense to develop apportionment rules to determine which country gets the proceeds. The proceeds could be allocated among G20 countries or globally (including to non-G20 countries), proportionally to population, to the amount of sales made in each country, to the value of the tangible capital stock, and to a combination of these (and other possible) factors. Importantly, the apportionment rule matters for the distribution of taxes but not for the tax burden, so that there is no incentive for companies to game the system. The apportionment rules for multinationals could be negotiated by the G20. It is also conceivable that the proceeds of this tax could be used to fund international organizations or for specific new global initiatives, e.g., to address the issue of climate change.

Why would G20 countries agree to such a tax? Corporate tax rates have declined drastically over the last 40 years, driven down by tax competition (Zucman 2014). Large valuable multinationals are the largest and most visible winners from globalization (and also the biggest beneficiaries of the race to the bottom in corporate taxes). Therefore, there is public demand for higher corporate taxes. The new Biden administration in the United States has indeed proposed to lead negotiations on a significant minimum corporate income tax on multinational corporations. The advantage of the wealth tax relative to the corporate profits tax is that it is easy to administer and very hard for companies to avoid. Our proposal complements current proposals for a minimum corporate income tax, as it would affect companies with high market values but little taxable income, in contrast to the corporate income tax. If the current international negotiation for a significant global minimum corporate income tax succeeds, an international negotiation for a modest wealth tax will be easier to achieve. If the current international negotiation fails, negotiating a more modest wealth tax might be an easier lift.

Notes: This figure shows the evolution of total private wealth in the United States, expressed as a fraction of GDP. Private wealth is the sum of the wealth of households and the wealth of non-profit institutions serving households. “Housing” includes both owner-occupied and tenant-occupied housing and is gross of any debt. “Fixed-income claims (net of debts)” includes all interest-generating assets (including those held through pension funds and insurance companies), net of all debts (mortgage and non-mortgage debt). “Private businesses” includes equity in non-corporate businesses (sole proprietorships and partnerships) and equity in unlisted corporate businesses (including S-corporations and private C-corporations). “Listed equity” includes household and non-profit equity in listed corporations, including equities held through pension plans and insurance companies. Source: Saez and Zucman (2016), updated, based on the Federal Reserve Financial Accounts.

Notes: This figure shows the share of pre-tax national income earned and the share of equity wealth owned by the top 1% highest pre-tax income earners in the United States. Pre-tax national income is income after the operation of the pension system but before taxes and government transfers. Equity wealth includes all corporate equities held directly and indirectly through pension funds and insurance funds, minus equity in S-corporations (which are all privately owned). That is, equity wealth includes listed equity wealth from Figure 1 plus equity in unlisted C-corporations, whose distribution cannot be estimated separately, but which is small on aggregate in recent years (less than 10% of US GDP as opposed to 150% of GDP for listed equities). To rank adults (and compute pre-tax income), income is split equally among married spouses. Source: Piketty, Saez and Zucman (2018), updated in Saez and Zucman (2020).

NOTES

1 Such fees are intended to allow the SEC to recover costs associated with its supervision and regulation of the U.S. securities markets and securities professionals (and hence are not a tax proper).

2 The average fee is 0.48 points on US$ 17 trillion in assets, that is, US$ 90 billion in 2018. This fee is slowly going down (it was about 0.94 points in 2000) as savers slowly learn and turn to low-cost passive index funds that charge only the cost-of-operation (less than 0.1 percentage points of asset value).

3 See also the estimates of stock market capitalization to GDP reported by the World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LCAP.GD.ZS

REFERENCES

Morningstar, (2019), U.S. Fund Fee Study for 2018, Chicago, Morningstar Research https://www.morningstar.com/lp/annualus-fund-fee-study

Piketty T., E. Saez, and G. Zucman, (2018), “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 133, no. 2, p. 553-609

Saez E. and G. Zucman, (2016), “Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 131, no. 2, pp. 519-78

Saez E. and G. Zucman (2019a), The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay, New York, W.W. Norton

Saez E. and G. Zucman, (2019b), Progressive Wealth Taxation, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 437-511

Saez E. and G. Zucman, (2020), Trends in US Income and Wealth Inequality: Revising After the Revisionists, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 27921, October

Saez E. and G. Zucman, (2021 forthcoming), “A Wealth Tax on Corporations’ Stock”, Economic Policy, April

Tørsløv T.R., L.S. Wier, and G. Zucman, (2018), The missing profits of nations, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 24701

Wong F., (2020), Mad as Hell: Property Taxes and Financial Distress, Working Paper, Available at SSRN 3645481

Zucman G., (2014), “Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits”, Journal of economic perspectives, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 121-48