A transborder network of households connects individual lives with global trends through domestic work. For migrant women, care and domestic work is often an entry point into the labour market. Yet discrimination and conflicts between policy regimes undermine their rights, dignity, and freedoms. Through transborder cooperation, the G20 can play a paramount role in ensuring decent livelihoods for migrant care and domestic workers. This policy brief outlines policy strategies related to care work, social protection, decent work, synergetic regulatory frameworks, and transnational coordination to guarantee migrant care and domestic rights.

Challenge

Care and domestic work are crucial for our societies, encompassing multiple activities aimed at meeting people’s physical, emotional, and psychological needs throughout their lives (ILO, 2018). Despite the vital nature of care, those who perform it are usually undervalued in terms of recognition and compensation. As women predominantly work in the sector, this situation becomes a gender matter.

Over the years, the internationalisation of care services has created “global care chains” (Hochschild, 2000). These chains involve households recruiting foreign women as caregivers, and these women then transfer their own care needs to other women in their home country. Thus, a transborder network of households connects individual lives with global trends through domestic work (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou et Thomas, 2022).

With limited opportunities in their home country, women move abroad looking for better life prospects. Domestic work, an extension of social reproductive responsibilities (Hennebry, Grass, and Mclaughlin, 2016), is often an entry point into the labour market for them. Working in private settings implies limited oversight and access to protection (Lenard, 2021) and scarce opportunities for collective representation (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou et Thomas, 2022). Job protection laws often grant fewer rights to domestic workers and even fewer to migrants. In addition, formal migration schemes usually restrict migrant care and domestic workers’ (MCDWs) entitlements compared to those enjoyed by citizens and long-term residents in destination countries (Baubock and Ruhs, 2021). Thus, discrimination and conflicts between migration, labour, and care policy regimes undermine MCDWs’ rights, dignity, and freedoms.

The pandemic has exacerbated inequalities, with migrants experiencing a higher incidence of the disease yet lower access to healthcare and vaccines (Ghosh and Chaudhury, 2021; Chan and Kuan, 2020). Mobility restrictions also limited emigration, returning home, and family reunification (Asis, 2020). The socioeconomic conditions of migrants have also severely deteriorated: they experienced higher unemployment, lower access to social protection, and limited state support.

MCDWs have traditionally been more vulnerable and less assisted during crises (Rao et al., 2021). Prospective migrants faced uncertainties regarding their departure as host countries continued to close borders (ILO, 2021). Those who had already migrated experienced multiple vulnerabilities. Mobility restrictions reshaped the residential and domestic spheres, which often became a space of domestic abuse and control. Risks were higher for live-in MCDWs, who increased their workload and dependence upon employers, especially those in sponsorship systems (Rao et al., 2021). Many households could not afford to hire workers anymore, which increased the risks of repatriation. Domestic workers’ special labour regimes (if any) and high informality limited their access to employment protection and COVID relief programs. Furthermore, returned migrants faced stigmatisation and discrimination, as people perceived them as a sanitary threat (Hoagland & Randrianarisoa, 2021; Harjana et al., 2021).

While some home and host countries have made efforts to improve the situation of MCDWs, guaranteeing their rights still proves elusive. Negotiations between independent states with different laws, asymmetric bargaining power, and conflicting interests can pose challenges. Migrants are also often excluded from decision-making and political processes. Overall, global care chains mesh migration, class, gender, labour, and care at a transnational level, requiring coherent multilateral approaches to guarantee rights.

Proposal

To improve livelihoods for MCDWs, governments and other stakeholders must act locally and transnationally by promoting a rights-based approach to managing migration. This perspective implies conceiving migration as a human-centred process that is life-changing for individuals and their families. Given the crucial contribution of MCDWs to both countries of origin and destination, these actions can be a win-win by contributing to both guaranteeing rights and benefiting economies.

The consequences that host and home countries face grant them rights and duties towards migrants. Transborder cooperation can address global systemic concerns, ensure decent livelihoods for MCDWs and advance gender equality. To this end, a new paradigm in which policies put life at their core is necessary. As a crucial forum for multilateral cooperation, the G20 can play a paramount role in this endeavour.

The topic is particularly relevant during the current G20 presidency: Indonesia has one of the largest migrant worker communities, estimated at around nine million people (World Bank, 2017). Half of them are women, usually employed as informal domestic workers. These migrants play a vital role in the Indonesian economy, providing remittances that can improve their families’ wellbeing and build local economies (World Bank, 2017). Yet despite their contribution to development, poor working conditions hinder their access to decent work and affect their wellbeing. Between 2011 and 2016, Indonesian migrant workers suffered more than 200,000 human rights violations (BNP2TKI, 2017), demonstrating the urgency to address the many challenges in the lives of MCDWs.

Prioritising care policies beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

While economies were described as “stalled” during the first phase of the pandemic, the care economy was arguably reaching a peak. Care was crucial to prevent the spread of the disease and address its consequences, becoming a priority for governments globally. Yet there is still a need to advance from implementing ad-hoc and siloed emergency interventions to creating comprehensive care systems.

A holistic transnational care scheme should recognise the value of care, reduce the burden of unpaid work, and redistribute it. This process involves not only the genders but also families, the State, the private sector, and the community. At the same time, such a policy scheme should ensure collective representation for care workers and reward them with adequate compensation and decent labour rights (ILO, 2018).

A comprehensive care scheme should include at least three relevant pillars: granting time to care through gender-sensitive parental leaves, providing quality childcare and long-term care services, and conceding money for families to fulfill their care needs. A necessary complement to these interventions would be the training of care workers; for migrants, it is also pertinent to facilitate skills portability and recognition (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou et Thomas, 2022).

Box 1: The Integrated National Care System (SNIC) of Uruguay

Uruguay’s care scheme represents a positive experience of national comprehensive policies and alliance building (Gammage et al., 2020). Launched in 2015 following a lengthy process of negotiation and consultation, the SNIC has five priorities (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social del Uruguay, 2020):

- Communication: promoting a cultural shift to value the right to care and redistribute care responsibilities more equally.

- Information and knowledge: advancing data collection, monitoring, and evaluation to assess the SNIC’s effectiveness.

- Regulation: establishing a legal framework for policy implementation, ensuring the right to care and decent labour conditions for care workers.

- Training: designing a training strategy for care workers to enhance quality and revalue paid care work.

- Services: expanding care services for early childhood, the elderly, and people with disabilities, including care facilities, family leaves and cash transfers.

By recognising the intrinsic and instrumental values of care work, the State highlighted the role of the SNIC to guarantee rights, promote gender equality, and foster wellbeing. The scheme, considered within Uruguay’s social protection matrix, had a double approach: to foster shared responsibility both within the community and between genders to overcome the sexual division of labour and revalue care work.

Building social protection floors for all, including migrants.

Social protection is a human right that cannot be denied to people based on their labour or migration status. Social protection can also create more inclusive and resilient societies by bringing positive effects for migrants, their families, and the development.

As the pandemic revealed the interdependencies of our mutual wellbeing and magnified our vulnerabilities (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou and Thomas, 2022), governments should advance towards universal social protection, including all migrants throughout the migration cycle. Such an approach should ensure income security, access to healthcare, and the portability of benefits across borders.

Migrants’ access to social protection is often hampered. The main causes include their status, citizenship, residence, employment period, conflicts between social security and migration laws, scarce information, and lack of coordination between home and host countries (ILO, ISSA & ILO-ITC, 2021). Granting access to social protection before, during, and after migration can facilitate the positive experiences of MCDWs in their countries of destination and their return and reintegration into their home countries.

Box 2: Indonesia’s migrant support at the local level

During the last decade, Indonesian local governments and NGOs have played an active role in providing social protection and information for villagers working abroad. Two initiatives stand out: the Village of Care for Migrant Workers (Desa Buruh Migran-Desbumi) and the Productive Migrant Village (Desa Migran Produktif-Desmigratif).

Both initiatives place the village at the forefront of efforts to protect migrant workers. Through these programmes, village governments work with local organisations, prospective and former migrant workers, and their families. The institutions provide information on migration options, procedures, and rights. They also handle cases and train people to develop skills and alternative sources of income. The services attempt to protect and prevent migrant workers from relying on inaccurate information from brokers or recruitment agencies.

Moreover, Desbumi and Desmigratif initiatives offer reintegration and empowerment programs for former migrant workers in Indonesia. These activities include skills training and capacity-building workshops. During the pandemic, Desbumi also provided healthcare services and shared its profits with its participants as a form of financial support. These experiences show how local-level initiatives can enhance the capacity of former migrants economically and socially while preventing risks in migration procedures.

Enacting policies to regulate and ensure decent work opportunities for migrant care work, granting access to labour rights and entitlements.

Decent working conditions in the care sector need to be scrutinised through a gender transformative lens. Female care and domestic workers often sustain relationships with their employers amidst unequal power dynamics. The inequalities further manifest among migrants.

Care workers are underrepresented in policy frameworks (Iyer and Chakraborty, 2021). In 2010, only ten percent of the domestic workers’ labour force was fully covered by general labour laws (ILO, 2013). A year later, the ILO launched the Domestic Workers Convention (C189) and Recommendation (R201), which set standards to ensure decent work after a long process of participatory deliberations. Few countries have ratified these instruments; within the G20, only Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Mexico, South Africa and some EU members (Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Malta, Portugal, Sweden and recently Spain). Protection gaps still abound, especially for migrants. MCDWs have restricted access to social security, decent wages, and formal opportunities, while they are more prone to situations of abuse and exploitative working conditions (ILO-OECD, 2018).

G20 countries must ratify ILO Convention 189 and monitor yearly progress. Each member state should then implement legal frameworks that grant domestic workers rights equal to those of other workers. Entitlements such as fair pay, employment protection, job stability, training, skills certification, social security, and rest days, among others, are paramount for decent work. The implementation of these policies requires strengthened law enforcement and inspections.

The G20 should advance a collective agreement that guarantees decent labour standards for migrant workers and monitors compliance. The process should involve multi-stakeholder dialogue between the governments, workers, employers, recruiting agencies, and civil society. The G20 offers an extraordinary space for deliberations, gathering many of the main sending and receiving countries. Negotiations should also envision enhanced social security coordination mechanisms that ensure equality of treatment and social security rights for mobile workers and their families (ILO-OECD, 2018).

Box 3: Fostering social dialogue in Argentina

In 2013, Argentina implemented a special labour regime for domestic workers that equated their rights to other workers in the economy. This scheme implied a substantial step towards greater equality. For the first time, it granted them basic labour rights: a minimum wage, social security, written contracts, holidays, and limits on working hours (Lexartza, Chaves & Carcedo, 2016).

Challenges are still ubiquitous: despite progress, informality reaches 75 percent of all domestic workers with few bridges between labour and migration schemes. Nonetheless, the regime created a space crucial for social dialogue: the National Commission for Domestic Work. This group gathers workers’ associations, employers’ organisations, and the national government to negotiate labour conditions. In its first four years, all stakeholders had described the commission, which created the first institutional sphere including domestic workers, as a positive experience (Pereyra, 2018). Domestic workers have achieved wage improvements and put forth claims about working conditions. Official negotiating tables might open a future chance to discuss the challenges faced by MCDWs.

Creating synergetic regulatory frameworks that ensure equal rights and dignity for migrant care and domestic workers.

Around the world, migration law often prevails over labour law. This situation aggravates in the case of special labour regimes such as those for domestic workers. For this reason, MCDWs with irregular status cannot claim their rights as workers (King-Dejardin, 2019).

Stronger synergies between migration and labour laws can enable better working conditions for MCDWs, bearing in mind the weight of migration in the care sector. To guarantee migrants’ fundamental rights and freedoms regardless of their status, migration regimes need to embrace and underscore human dignity. Schemes should promote formal job opportunities, regulate recruitment processes, guarantee access to justice and dispute settlement, promote family reunification, and ensure access to social protection. In certain countries, sponsorship systems would need revision to achieve this goal (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou & Thomas, 2022; Rao et al., 2021).

Pursuing policy coherence and synergies at the international level can also reap benefits. Dialogue and cooperation between governments, civil society, and workers’ organisations could foster the assessment of transnational consequences of national interventions and prevent undesired effects.

While G20 leaders have committed to continuing dialogue on migration since 2018, concrete actions are needed. Following experiences such as the UN’s Migration Network Hub, the G20 could create a community of practice to ensure labour standards and social security for migrants, including MCDWs. A G20 Global Migration Network (GMN) could strengthen collective action by facilitating dialogue, disseminating best practices and ensuring better coordination among countries, in pursuit of the goals of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

Box 4: Are migration barriers and bans effective for guaranteeing MCDWs’ rights?

In South Asia, many governments have imposed control over women’s mobility and migration as a strategy to protect workers who travel abroad for employment. Such policies involve barriers or bans for women from migrating based on age, skills, motherhood, or guardianship. For instance, India requires an emigration check for all workers with less than ten years of education and nursing professionals emigrating to G20 countries like Indonesia and Saudi Arabia; both groups are mainly women. Nepal, in turn, has banned its citizens from travelling to Gulf countries for jobs as domestic workers.

Evidence of the positive effect of bans on migrants’ working conditions and livelihoods is weak. These measures have been described as “lazy”, as alternatives require an active stakeholder role in bi/multilateral negotiations and coordination (Lenard, 2021). Only exceptionally sending countries have achieved greater bargaining power.

Strict, paternalistic regulations, even when meant to be a diplomatic tool, increase informal migration and risks for women (Shivakoti, Henderson & Withers, 2021). A sizeable proportion of the international migration goes underground, as women use clandestine routes or improper documentation (Deshingkar, 2021). Migration barriers also raise costs for female workers, especially for deprived women. MCDWs then face heightened vulnerabilities, further thwarting their ability to access decent working conditions abroad and bargain for better wages and social security.

The role of the G20 in fostering transnational coordination

The G20 is a unique forum to promote coherent transnational approaches through collective work (Lay et al., 2017). Benefits for migrants, home countries, and host countries can only materialise when all the interests are fairly represented and accommodated in decision-making processes (Baubock & Ruhs, 2021). While not binding, the G20 provides a platform to foster multilateral agreements, commitments, and exchanges. The involvement of multiple stakeholders offers an opportunity to discuss strategies, policies, and transborder consequences of domestic measures (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou & Thomas, 2022; Caro Sachetti et al., 2018).

Migration issues usually entail some kind of power asymmetry, with destination countries holding a stronger bargaining position than countries of origin and migrants. This situation hampers workers from claiming their rights and debilitates the potential of origin countries to protect their citizens abroad. The participation of international organisations in the G20 could facilitate a convening role in discussions that could mitigate this imbalance (Baubock & Ruhs, 2021).

To maintain priorities across G20 leaderships, the role of the troika in defining a shared policy agenda on the topic is vital. The different G20 engagement groups could provide inputs to this end, advancing multi-stakeholder, multi-level alliances and policy proposals.

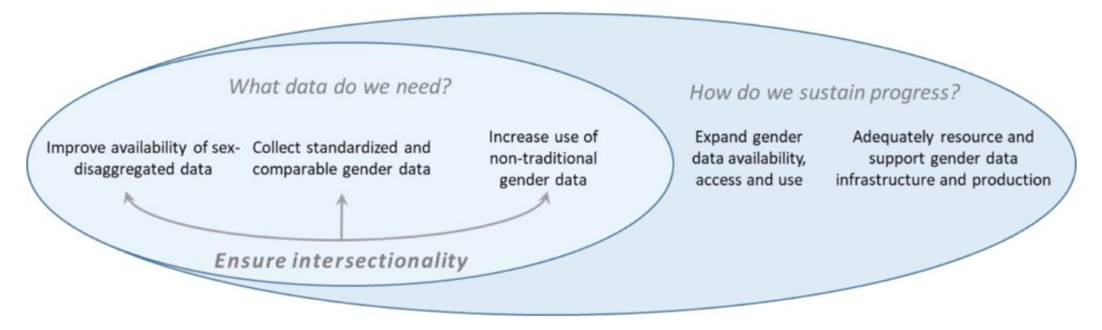

Moreover, gender data gaps (Figure 1) influence global migration governance and women’s livelihoods (IOM, 2021). The absence of shared definitions and the scarcity of reliable data (on migrants’ journeys, demographic background, health status, economic contribution, etc.) foster policy incoherence, insufficient protection, and lack of migrant-sensitive policies.

The proposed GMN could improve data collection, availability, integration, and harmonization. Quality, gender-disaggregated data is paramount to accurately diagnose the situation, identify migration drivers, track migrants’ wellbeing across borders, assess intersecting inequalities, and understand the role of countries in global care chains (Caro Sachetti, Díaz Langou & Thomas, 2022). In addition, rigorous research is crucial to spot best practices and offer evidence-based policy proposals.

Figure 1: Five Key Gender Gaps and Challenges in Migration Data

![]()

Source: IOM (2021)

To collect quality data, the G20 should agree on a common framework that establishes common indicators and definitions, integrates data frameworks, and employs information technology. In this process, the four key interrelated elements necessary for strengthening gender data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: A Framework for Strengthening Gender Measures and Data

Source: ILO (2021)

As people are increasingly on the move around the world, it becomes ever more relevant to discuss novel social welfare schemes beyond the nation-state level to guarantee social protection for individuals regardless of their place of residence. The demographic transition and the increasing need for care will likely keep the demand for care and domestic workers high, turning these schemes especially relevant for this population. Multilateral fora such as the G20 provide an opportunity to discuss and reimagine social protection and labour policies at the transnational level. These debates should include considerations for the transfer and portability of welfare benefits across borders. Such efforts could scale up current regional approaches to address challenges in key migration corridors.

To foster social, economic, and gender justice across borders, we cannot overlook the geographic dimensions of care. The policies outlined in this policy brief aim to address the challenges prevailing at the crossroads of care, labour, and migration regimes to guarantee the rights of MCDWs from a human-centred perspective. By advancing in these realms, the G20 can take the global lead in improving livelihoods for all.

References

Asis, Maruja, M.B. (2020). Repatriating Filipino Migrant Workers in the Time of the Pandemic. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Baubock, R., & Ruhs, M. (2021). The Elusive Triple Win: Can temporary labour migration dilemmas be settled through fair representation? Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper No. RSC, 60.

BNP2TKI. (2017). Data Penempatan dan Perlindungan PMI Periode Tahun 2018. Jakarta: BNP2TKI.

Caro Sachetti, F., Díaz Langou G. & Thomas, M. (2022). Migrant care and domestic workers beyond the Covid-19 crisis: a call to action for transnational cooperation. Global Solutions Journal, Issue 8. Berlin: Global Solutions Initiative.

Chan, Lai Gwen & Kuan, Benjamin (2020). Mental health and holistic care of migrant workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Health 10(2): 020332.

Deshingkar, P. (2021). Human smuggling, gender and labour circulation in the Global South. The Routledge Handbook of Smuggling, 326-340.

Gammage, S., et al (2018). The Imperative of Addressing Care Needs for G20 Countries. T20 Policy brief. Gender Economic Equity Taskforce. Buenos Aires: T20 Argentina.

Ghosh, Ambar Kumar & Chaudhury, Anasua Basu Ray (2021). Migrant Workers and the Ethics of Care during a Pandemic, in India’s Migrant Workers and the Pandemic. London: Routledge.

Harjana, N., Januraga, P. P., Indrayathi, P. A., Gesesew, H. A., & Ward, P. R. (2021). Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Repatriated Indonesian Migrant Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in public health, 9, 630295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.630295

Hennebry, J., Grass, W., and Mclaughlin, J. (2016). Women Migrant Workers’ Journey Through the Margins: Labour, Migration and Trafficking. Research Paper. New York: UN Women.

Hennebry, J., KC, H., & Williams, K. (2021). Gender and Migration Data: A Guide for Evidence-based, Gender-responsive Migration Governance. Geneva: IOM.

Hidayah, Anis. (2018). “Restoring the rights of Indonesian migrant workers through the Village of the Care (Desbumi) program,” in Indonesia in the New World: Globalisation, Nationalism and Sovereignty, edited by Arianto Patunru, Mari Pangestu, M. Chatib Basri, 225-242. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishaq Institute.

Hoagland, N., & Randrianarisoa, A. (2021). Locked down and left out. Red Cross Red Crescent Global Migration Lab, Australia.

Hochschild, Arlie R. (2000). “Global care chains and emotional surplus value.” In On the Edge: Living with Global Capitalism, edited by Will Hutton and Anthony Giddens, 130–46. London: Jonathan Cape.

Huang, S. & Yeoh, B. (2007). Emotional Labour and Transnational Domestic Work: The Moving Geographies of ‘Maid Abuse’ in Singapore, Mobilities, 2:2, 195-217, DOI: 10.1080/17450100701381557

ILO (2013). Domestic workers across the world: Global and regional statistics and the extent of legal protection. ILO: Geneva.

ILO (2018) Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

ILO. (2021). Supporting Migrant Workers during the Pandemic for a Cohesive and Responsive ASEAN Community. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

ILO. (2021). How to Strengthen Gender Measures and Data in the Covid-19 Era. https://ilostat.ilo.org/how-to-strengthen-gender-measures-and-data-in-the-covid-19-era/

ILO-OECD (2018). Promoting adequate social protection and social security coverage for all workers, including those in non-standard forms of employment. Geneva: ILO. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—inst/documents/publication/wcms_646044.pdf

ILO, ISSA & ITC-ILO (2021). Extending social protection to migrant workers, refugees and their families: a guide for policymakers and practitioners. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—migrant/documents/publication/wcms_826684.pdf

Iyer, S., & Chakraborty, A. (2021). Unpacking women’s associational. Migrants, Mobility and Citizenship in India. Routledge Publication

King-Dejardin, Amelita (2019). The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work. At the Intersection of Care, Migration and Gender. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Kontan Online News (2022, Jan 28). Kemnaker telah bangun 450 desa migran poduktif, ini tujuannya (The Ministry of Manpower has built 450 villages of Desmigratif, here they are the objectives), https://nasional.kontan.co.id/news/kemnaker-telah-bangun-450-desa-migran-produktif-ini-tujuannya, retrieved in 10 April 2022.

Lay, Jann, Clara Brandi, Ram Upendra Das, Richard Klein, Rainer Thiele, and Nancy Alexander (2017). Coherent G20 policies towards the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. G20 Insights.

Lenard, P.T. (2021). Restricting emigration for their protection? Exit controls and the protection of (women) migrant workers, EUI RSC, 2021/62, Migration Policy Centre – https://hdl.handle.net/1814/72061

Lexartza, L.; Chaves, M. J. & Carcedo, A. (2016). Políticas de formalización del trabajo doméstico remunerado en América Latina y el Caribe. Oficina Regional para América Latina y el Caribe, FORLAC. Lima: OIT.

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social del Uruguay (2020). Sistema Nacional Integrado de Cuidados Informe de la Secretaría Nacional de Cuidados. Informe de transición. Montevideo: MIDES

Pereyra, F. (2018). Cuando la expansión de derechos es posible: el diálogo social de las trabajadoras domésticas en Argentina. Serie Documentos de Trabajo 26. Oficina de País de la OIT para la Argentina. Buenos Aires: OIT.

Rao, S., Gammage, S., Arnold, J., & Anderson, E. (2021). Human Mobility, COVID-19, and Policy Responses: The rights and Claims-Making of Migrant Domestic workers. Feminist Economics, 27(1-2), 254–270.

Shivakoti, R., Henderson, S., & Withers, M. (2021). The migration ban policy cycle: a comparative analysis of restrictions on the emigration of women domestic workers. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 1-18.

The World Bank (2017). Indonesia’s Global Workers: Juggling Opportunities and Risks. Jakarta: The World Bank.