Young people can be the drivers of inclusive transformation. Nonetheless, with low levels of financial literacy and even lower employment opportunities, they are faced with severe challenges.

Young people and women must be encouraged to seize the opportunities of the digital age and the circular economy to actively participate in the financial sector. A financially aware and inclusive culture, which ensures access to financial products and services at both the local and the international level, must be promoted, leveraging the advantages of digitalisation.

Challenge

Progress towards a significant reduction of Illicit International Financial Flows (IIFF) has been slow, reflecting several factors: e.g. data on financial interlinkages are not apparent from Direct Investment (DI) statistics; a comparison of inward DI data compiled by various Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries has revealed major inconsistencies due to the use of different small DI databases rather than a comprehensive dataset; measuring pass-through funds is complicated and information-intensive; and it is difficult to determine who ultimately owns and controls investments (UBOs), in part because the complex shareholding patterns associated with multinationals cannot easily be disentangled, and because relatively small shareholdings can sometimes translate into significant levels of control. The efforts made to develop a UBO Identification tool kit to assist countries in implementing the method that best suits their legal and policy frameworks, have highlighted how difficult it is to reach an international standard.

The current approach of gathering more and more data and refining the domestic legal arsenals is increasingly costly and time-consuming. It is also difficult to implement. The result is that transparency in IIFF remains an issue, while some de facto UBOs continue to fly under the legal radar and others can use their network of subsidiaries for unethical purposes. A new approach, combining parsimony and effectiveness, is needed.

We propose a “risk-based” approach to identifying possible UBOs. In the same way that a risk-based approach has facilitated the adoption of transparency standards for banks (the Basel Principles), the methodology we propose could constitute the basis for the gradual adoption of an international standard. It is robust and solidly anchored on proven theoretical grounds. The proposed methodology would be cheaper and more efficient than the current practices, and would increase transparency.

Proposal

The advent of FinTech has brought the realisation that both financial education and consumer protection systems are vital elements in the process of social empowerment and financial growth (OECD 2017), yet not enough policy measures have focused on such aspects. Efforts must be made to build a new and better economic scenario in which all individuals are able to participate fully and equally, thus reaching their highest potential (Chamboko and Heitmann 2018).

Financial inclusion is the focal point of extensive international debate because of its ability to foster sustainable economic growth, both at the macro and micro levels, by focusing on the more vulnerable social groups (FIAP 2017). As a matter of fact, at the G20 Summit in China (2016), G20 leaders explicitly recognised the critical importance of financial inclusiveness to “ensure that economic growth serves the needs of everyone and benefits all countries and all people, including in particular women, youth and disadvantaged groups” (FIAP 2017, p. 7).

In 2016, the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI)1 presented the High-Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion which focused on the development of inclusive financial systems and stressed the importance of financial literacy through the promotion of educational programmes (GPFI 201).

The 2017 Financial Inclusion Action Plan further demonstrates how both the GPFI and the G20 have shown explicit interest in taking steps towards a more financially inclusive global society. Notwithstanding, governments must increase their efforts and tailor action plans according to the target audience.

FINANCIAL LITERACY

Financial literacy is a pivotal element in achieving greater gender inclusion, social protection, and a more widespread economic-financial culture. Financial education programmes significantly improve access to services and products, including the mobile financial services that have become increasingly popular in low and middle-income African countries.

We therefore urge G20 members to introduce compulsory financial education programmes in the school curricula to reach a larger pool of students in an effective and rapid manner and intervene from an early age, in line with suggestions by the OECD INFE Guidelines on financial education. Such courses ought to be implemented so that students are able to build a solid financial foundation by developing more secure and money-saving behaviour. A unified financial handbook aimed at providing basic economic and financial knowledge must be provided to all students in all schools. Governments must ensure that the national implementation of compulsory courses in schools is supported by the provision of standardised but constantly updated guidebooks. By using such handbooks as the substructure of their teaching programme, teachers will not have to receive extensive training, thus cutting down on both the costs and time frames. Students will also be able to learn independently, thus benefitting out-of-school pupils. Policymakers and other relevant stakeholders ought to be involved in the process of ameliorating financial literacy within the education sector. This can be done at different stages in the conceptualisation and implementation of financial education programmes. For example, during the design of financial education tools, a blueprint “international” version of a financial handbook that has been found to be effective in most contexts could be used and adapted by local experts in each country to suit local contexts. This will not only ensure compliance with the national financial system but will also result in a product whose design and delivery mechanism are suitable for local populations. By redesigning and localising handbooks according to each country’s necessities, the knowledge delivered will be more relevant and the outcome will have a more positive effect on financial literacy levels. A 2016 project based in Italy, where financial handbooks were delivered to numerous schools, showed that, in addition to promoting teacher training and extending the appreciation of the subject, the provision of practical material also increased young people’s awareness of the issues of conscious money management as well as the importance of acquiring financial skills. When asked, more than 68% of the teachers involved stated that with the use of the financial handbook, teaching was facilitated, and students gained from it (GLT 2016). With a greater spread of financial culture, communities have benefitted from a higher level of financial and social inclusion.

However, it is important to consider the possible challenges of such an approach: implementing school-based financial education courses may not always be possible due to geographical and infrastructural constraints (OECD 2020b). Furthermore, it is important to consider students who are not in school education systems and would therefore be excluded from learning. To deal with such obstacles, we recommend the use of technological tools to deliver out-of-school training programmes. Digital delivery of financial education will also benefit vulnerable groups that may not have access to training opportunities due to geographical barriers. By delivering educational programmes digitally, the attainment of financial inclusion becomes more feasible, given that 67% of the world’s population now has access to technological and digital instruments (Lyons, Kass-Hanna, Liu, Grenlee, and Zeng 2020b). The promotion of digital tools for budgeting, saving and goal trackers, just like educational apps and tutoring websites, is also vital for skills development. Nonetheless, there is a probability that young people will self-select into financial education. To encourage participation to these programmes, effective communication must be used to make financial education more attractive. The use of technological tool, namely social platforms, podcasts, and informative videos would be an efficient way to increase participation. Within the scholastic realm, activities based on simulation of real-life economic scenarios and competitions between students have proved to have a positive effect on the engagement rate. It is important to note that children from low-income backgrounds may not necessarily have access to such materials: both local contexts and age groups must therefore be considered when designing programmes, and use made of locally available/easily accessible materials.

The digitalisation of societies is growing in tandem with the need to deliver financial education digitally. Digital education programmes have the potential to reach broader audiences (OEC, 2021) and therefore allow an all-inclusive global action plan. The G20 must work on the implementation of digitalised and innovative tools that respond to technological evolution in the financial sector (OECD/INFE 2018). It is crucial to provide a tailor-made approach to digital learning activities to engage individuals and entrepreneurs in teaching methods that mirror current technological systems (OECD 2021).

Increased use of mobile phones provides an opportunity for consumers to have greater access to mobile financial services and financial education. In Kenya, for example, innovative services such as MPESA have led to a significant uptake in mobile financial services and reduced transactional costs (Njuguna 2021). A study in Ethiopia found that financial training coupled with frequent reminders via SMS improved financial literacy scores and resulted in increased short-term deposits by owners of micro-businesses (Abebe, Tekle, and Mano 2018). However, low digital skill levels and limited availability of technological tools should be taken into consideration. While national policies aimed at tackling the digital divide should include technological training programmes, they should also address the lack of access to digital tools and associated infrastructures. It is vital to recognise digitalisation as an immediate policy concern. Public-private partnership initiatives offering low-cost technological tools must be encouraged as they are a potential solution to the affordability challenges that limit access to modern instruments and tools. To cater for the technological needs of children from particularly low-income backgrounds, governments could also provide digital devices like cell phones, computers or tablets. In Kenya, the government has a digital literacy programme, Digischool, which aims to improve access to digital technology within schools. As part of this programme, tablets are provided to all pupils in public schools and laptops are allocated to teachers. While the initiative currently covers mainly young children, it could be expanded to include older children and adolescents and the programme could be used as a platform to deliver digital financial lessons. Access to internet connectivity remains a challenge: governments should therefore support and invest in the expansion of ICT-related infrastructures and offer low-cost internet access in conjunction with internet providers.

FINANCIAL INCLUSION AND YOUNG PEOPLE

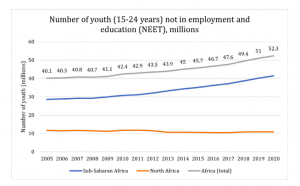

Youth employment remains an important policy concern for many governments in Africa. One in every five young people are NEET (ILO 2020a) (see Appendix A). The youth unemployment rate in Africa was estimated at 10.6% in 2020, although the figure was much higher in North Africa (30%). Within countries, unemployment tends to be more prevalent among rural and poorer groups, compared to more urban and higher income ones. Many youths are also underemployed, working fewer hours or employed in positions that are low paying or where their skills are underutilised. In addition, those who are employed are often found in precarious and informal employment with low incomes and no access to adequate social protection. In Africa, young people are more likely to have informal jobs (23%), to be unemployed (32%) and be dependent on remittances (74%) (OECD 2020a, p. 19). Often, the underlying reason relates to the lack of opportunities rather than the absence of motivation to work.

Reducing unemployment and underemployment requires both demand and supply side interventions. Policies should address supply-side constraints through the elimination of knowledge gaps and support for a skills revolution through public-private partnerships. It is imperative to work directly with individuals in up-skilling and re-skilling initiatives that include career guidance and orientation support. Vocational training must be strengthened to generate more value in the labour market by equipping young people with skills that meet current needs. It is also essential to integrate the needs of the labour market within the educational system to develop skills that meet current and future requirements. Efforts should focus on the attainment of smoother school-to-work transition by developing effective active labour market initiatives for young jobseekers.

Demand-side interventions to improve access to employment opportunities that offer higher income levels and adequate social protection should be supported too. This can be done by supporting sectors that have the potential to significantly improve youth employment, including industries without smokestacks (telecommunications, financial services, and tourism etc.), or by supporting more traditional industries that offer decent jobs. The G20 and African governments should support youth employment sectors and promote equal access to opportunities for all young people. Policymakers should also focus on national strategies and policy implementations that stimulate economic growth, including supporting more conducive business environments that encourage enterprise development by young people. This also involves improving access to low-interest credit from formal financial institutions or government schemes.

To cater for young people transitioning out of the education system into employment, governments should strengthen the provision of apprenticeship and traineeship programmes. However, these programmes can be exclusionary and may not necessarily benefit a large proportion of young people (Mckenzie 2017). Therefore, efforts should be put in place to make these opportunities more accessible to rural and poor youth through the provision of social assistance programmes, including cash transfers tailored to young people to provide income support and cater for basic needs, including food and transport, particularly as they seek better paying and more permanent employment opportunities.

Lack of productive opportunities coupled with inadequate access to financial services results in the financial exclusion of youth. Indeed, nearly half of the world’s young adults are reported to be financially excluded, yet the rate is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa region where only 40% of youth are financially included compared to 84% in high-income countries (OECD 2020a). This in turn contributes to the high levels of poverty and inequality that affect young people.

Studies that have assessed youth entrepreneurship levels have shown that financial literacy remains a challenge for many, including those with tertiary-level education. Higher rates of self-employment are found among those with lower levels of education; financial education levels are also lowest amongst self-employed youth and those running small-and-mediumsized enterprises (SMEs).

Financial literacy can be instrumental in improving young people’s participation in the labour market and improving financial inclusion. Higher financial literacy has been shown to have many positive effects on young entrepreneurs, including on savings accumulation and access to formal credit, better interest rates as well as business decision-making (Nkundabanyanga et al. 2014; Abubakar 2015, Abebe, Tekle, and Mano 2018). One study in Tanzania found that those who participated in entrepreneurship skills programmes, which included financial literacy, acquired 97% more savings knowledge, and that there was a 16.5% increase in financial decision-making at the household level (Krause, McCarthy, and Chapman 2016). Financial education also enables work preparedness and provides youngsters with the necessary tools to engage in the labour market (Osikena and Ugur 2016). Several studies from across Africa also find a positive effect on the growth of SMEs, with impact on both financial and non-financial aspects (see for example Cherotich, Ayuya, and Sibiko 2019)the exact effect of financial literacy on small-scale enterprise performance has not been fully identified in Ghana, hence the need for the present study. This study examines the effect of financial literacy (awareness, attitude and knowledge.

Evidence suggests that access to financial literacy by young people should be increased to ensure better financial inclusion and performance for their enterprises and improved welfare levels. Financial literacy programmes can also be included as part of the training offered to youth accessing enterprise grants offered by governments or the private sector. Given the expansion of social cash transfers in Africa, including those targeted at young people, there is an opportunity to improve financial literacy levels by delivering financial education to grant beneficiaries. Additionally, financial literacy needs to be coupled with other interventions to ensure maximum positive impact, including access to formal and favourable credit for SMEs.

GENDER INEQUALITIES AND FINANCIAL INCLUSION: FINANCIAL LITERACY, DIGITALISATION, AND THE LABOUR MARKET

Women are disproportionately affected by financial exclusion. Women’s empowerment, especially at the economic level, is critical for both sustainable and economic development as it contributes to the attainment of equal rights. Additionally, it also contributes to higher economic growth rates through increased employment and higher income levels (Larsen, Saugestad, and Løvstad 2019).

Gender inequalities stem from social and structural behaviour: gender-based violence intersects with other forms of oppression and financial exclusion. For this reason, already vulnerable groups of women must receive immediate protection and financial education to prevent them from falling into the vicious cycle of economic violence. Awareness ought to be raised about such phenomena by implementing social programmes and initiatives or through the distribution of informative materials. Programmes could include public services and helpdesks to assist women who are victims of violence.

Collaboration, cooperation, and communal effort is required to eliminate persistent disparities (UNICEF 2020). We must implement policy changes to instil female empowerment from a young age by promoting equal access to financial activities and digital instruments. In Uganda for example, only 41% of women compared to 59% of men, use mobile phones for financial transactions, and the women who use digital channels for financial purposes tend to be younger and better informed than average (Chamboko and Heitmann 2018). Women’s adoption of digital technology should be effectively promoted by the government, by the private sector and by civil society.

Government policies and strategies to increase employment should also respond to gender disparities in the labour market. Women are often excluded from sectors that offer well-paying opportunities and are also less likely to have access to formal and more favourable credit, partly due to a lack of assets to offer as collateral to financial institutions and low levels of financial education. The direct correlation between financial inclusion and socio-economic prosperity further emphasises the need to close gender gaps in labour markets and financial inclusion. One of the underlying reasons we advocate for the provision of support at an early stage is the need to protect adolescent girls and support them to achieve their maximum potential. In various parts of the world, young girls are forced to leave school to participate in household activities and/or are married off early. Skills development is particularly important as it provides women and young girls with an opportunity to participate, even if at a later stage, in both the labour market and the financial system (Africa Gender Index 2020).

MONITORING THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERVENTIONS

Policymakers should also support production of high-quality data to monitor financial literacy, financial exclusion levels, and policy implementation. These themes are not adequately addressed in many large-scale individual or household-level surveys, and their inclusion will generate data essential to policymaking and improving interventions. Collection of such data should also be harmonised to allow comparability within and across countries. Prior to the commencement of financial education programmes, research should be undertaken to assess skills and competencies and to identify gaps. Evaluations should also be carried out to establish impact and findings used to improve programme design and to scale up implementation. The delivery of financial education via technology platforms will facilitate the virtual monitoring of programme uptake and individual progress.

In conclusion, financial literacy, the availability of financial tools, and employment are some of the most important interventions needed to promote agency among the vulnerable, particularly in rural areas of the Global South.

APPENDIX A

Source: ILO, (2020), World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2020 https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2020/WCMS_734455/lang–en/index.html

APPENDIX B

PERSPECTIVE OF THE YOUTH

During last year’s G20 Summit 2020 in Saudi Arabia, the G20 Young Entrepreneurs’ Alliance, in promoting youth entrepreneurship as a driver of economic renewal, job creation and social change, stressed the importance of and the need to create a new generation of sustainable and inclusive growth (G20 YEA 2020). In a context of focusing all efforts on the so-called new generation, we must place the voices of the young at the centre of all discussions. If a collective organisation of the world’s top young entrepreneurs proposes measures to diversify financing opportunities, urges consideration of educational and skills-building programmes that enable young people to connect and to bolster growth of a sustainable economy, and calls upon the establishment of a standard technology development policy across the G20 (G20 YEA 2020), it becomes clear that we must take action and bring on the collectively desired change. The fact that the Y20 Summit the official youth engagement group of the G20 in Italy will be held for the first time in history further suggests how youth must be the pivotal element of all policy planning agendas. The priority areas of the Y20 Young Ambassadors Society vary from inclusion to sustainability and innovation (YAS 2021). The perspective on which the latter focuses is precisely our point of interest as importance is given to both digitalisation and the future of work. As a matter of fact, in an assessment carried out by the Y20, it emerges how young people in Italy, precisely 43%, considers “jobs and the future of work” as well as “education and culture” to be an important priority and deems innovative solutions to be the best course of action (Y20 2021). Given the list of priorities that will be addressed during the G20 Summit, it is evident that global leaders must respond to the concerns of the younger generations by providing rapid solutions especially with regards to the prosperity of the people and in favour of financial and social inclusion.

NOTES

1 Participating countries were Austria, Bulgaria, Colombia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Georgia, Germany, Hong Kong (China), Hungary, Indonesia, Italy, Korea, Malaysia, Malta, Moldova, Montenegro, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Republic of North Macedonia, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, and Thailand.

2 The Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion was established at the 2010 G20 Summit in Seoul.

3 International Network on Financial Education.

4 The AERC is currently running a research project in collaboration with the INCLUDE Knowledge Platform, the Economic Research Forum, and the Overseas Development Institute that seeks to identify sectors with the highest potential to create jobs for youth. https://includeplatform.net/theme/growth-sectors-for-youth-employment/

REFERENCES

Abebe G., B. Tekle, and Y. Mano, (2018), “Changing Saving and Investment Behaviour: The Impact of Financial Literacy Training and Reminders on Micro-business”, Journal of African Economies, vol. 27, no. 5

Abubakar H.A., (2015), “Entrepreneurship Development and Financial Literacy in Africa”, World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, vol. 11, no. 4

Africa Gender Index Report, (2020), What the 2019 Africa Gender Index tells us about gender equality, and how can it be achieved, African Development Bank Group, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, March.

Barbieri D. et al., (2020), Gender Equality Index 2020, ‘Digitalisation and the Future of Work’, Publications Office of the European Union, European Institute for Gender Equality

Chamboko R. and S.V. Heitmann, (2018), Women and Digital Financial Services in Sub-Saharan Africa: Understanding the Challenges and Harnessing the Opportunities, Field Note 10, MasterCard

Cherotich J., O.I. Ayuya, and K.W. Sibiko, (2019), “Effect of financial knowledge on performance of women farm enterprises in Kenya”, Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 294-311

Demirgüç-Kunt A., K. Leora, S. Dorothe, A. Saniya, and H. Jake, (2018), “The Global Fin dex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution”, Overview booklet, Washington DC, World Bank

FIAP, (2017), G20 Financial Inclusion Action Plan, Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, July https://www.gpfi.org/publications/g20-financial-inclusion-action-plan-fiap-2017

Global Thinking Foundation (GLT), (2016), Glossary Words of Economics and Finance, Social Impact Assessment, Analysis of the gathered data after the second updated version of the Glossary, according to the evaluations received from the target audience and the school network of Giunti Editore, GLT

Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion GPFI, (2016), G20 High Level Principles for Digital Financial Inclusion, G20 China 2016, GPFI https://www.gpfi.org/publications/g20-high-level-principles-digital-financial-inclusion

G20, (2019), G20 Fukuoka Policy Priorities on Aging and Financial Inclusion, G20 Japan 2019 https://www.gpfi.org/publications/g20-fukuoka-policy-priorities-aging-and-financial-inclusion

International Labour Organization (ILO), (2020a), World Employment And Social Outlook: Trends 2020, International Labour Organization, ILO, Geneva https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2020/lang–en/index.htm

International Labour Organization (ILO), (2020b), “Where is youth unemployment highest”, Youth unemployment trends, ILO, Geneva https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/multimedia/maps-and-charts/enhanced/WCMS_600072/lang–en/index.htm

Klapper L., A. Lusardi, and P. Van Oudheusden, (2015), Financial Literacy around the World, Washington DC, Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey

Krause B.L., A.S. McCarthy, and D. Chapman, (2016), “Fuelling financial literacy: estimating the impact of youth entrepreneurship training in Tanzania”, Journal of Development Effectiveness, vol. 8, issue 2

Larsen G., J.E. Saugestad, and H. Løvstad, (2019), Investing in gender equality, CARE Norway, Storebrand Asset Management, PwC Norway, June

Lyons, A.C., J. Kass-Hanna, F. Liu, A.J. Greenlee, and L. Zeng, (2020a), Financial literacy around the world: insights from the Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey

Lyons, A.C., J. Kass-Hanna, F. Liu, A.J. Greenlee, and L. Zeng. (2020b). Building Financial Resilience through Financial and Digital Literacy in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, ADBI Working Paper 1098, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo

McKenzie D., (2017), “How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence”, World Bank Research Observer, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 127-54 doi:10.1093/wbro/lkx001

Nkundabanyanga S.K., D. Kasozi, I. Nalu kenge, and V. Tauringana, (2014), “Lending Terms, Financial Literacy and Formal Credit Accessibility”, International Journal of Social Economics, vol 41, no. 5

Njuguna N., (2021), A Digital Financial Services Revolution in Kenya: The M-Pesa Case Study, African Economic Research Consortium

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (2017), G20/ OECD INFE Report on Adult Financial Literacy in G20 Countries, Paris, OECD https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/G20-OECD-INFE-report-adult-financial-literacy-in-G20-countries.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (2018), Financial Inclusion and Consumer Empowerment in Southeast Asia, OECD & International Network on Financial Education INFE, Paris https://www.oecd.org/finance/Financial-inclusion-and-consumer-empowerment-in-Southeast-Asia.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (2020a), OECD/ INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy, Paris, OECD https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/oecd-infe-2020-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (2020b), Advancing the Digital Financial Inclusion of Youth, Paris, OECD https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/financial-education/advancing-the-digital-financial-inclusion-of-youth.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (2021), Digital Delivery of Financial Education: Design and Practice, Paris, OECD https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/Digital-delivery-of-financial-education-design-and-practice.pdf

Osikena J. and D. Uğur, (2016), Enterprising Africa: What role can financial inclusion play in driving employment-led growth?, The Foreign Policy Centre, UK

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), (2020), Towards an equal future: Reimagining girls’ education through STEM, New York, UNICEF https://www.unicef.org/media/84046/file/Reimagining-girls-education-through-stem-2020.pdf

World Bank, (2018), Financial Inclusion Overview https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview

YAS, (2021), Young Ambassadors Society, G20 Youth Summit, Italy https://www.youngambassadorssociety.it/application2021y20/

YEA, (2020), G20 Young Entrepreneur’s Alliance 2020 Saudi Arabia Summit Communiqué, signed 30 October by the member organizations of the G20 Young Entrepreneurs’ Alliance https://yea20saudi.org

Y20, (2021), A Youth Perspective on the G20 Italy 2021 Agenda, Young Ambassadors Society https://www.youngambassadorssociety.it/youth-g20-agenda/