Abstract

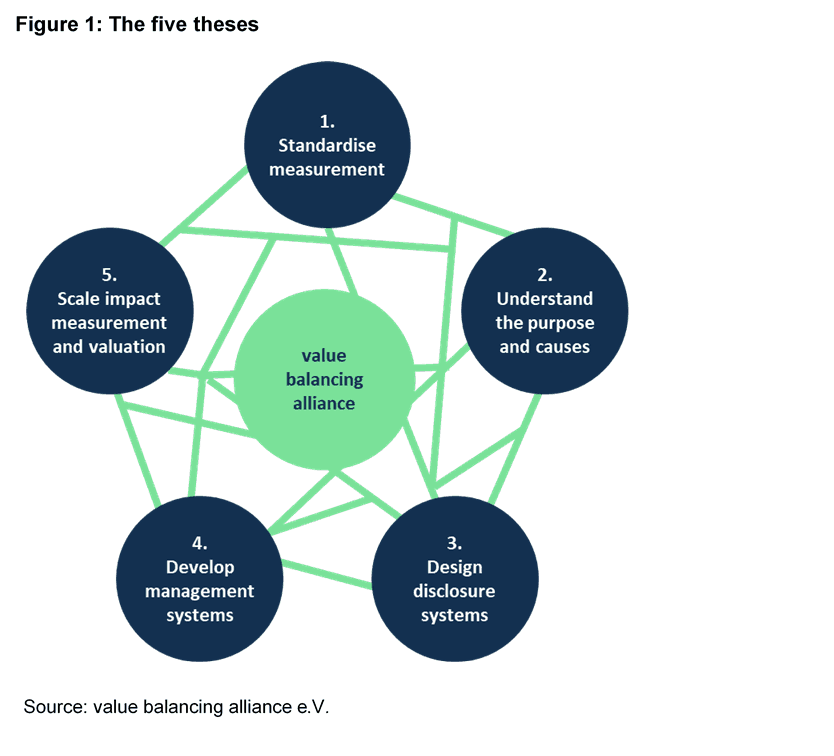

Our article builds a bridge between the global community of policymakers and various actors who are currently involved in crafting new concepts and standards to assess the social and environmental impact of companies. We map the fragmented landscape and show how a cross-sector partnership to balance financial, social, and environmental value can be built. We propose five theses against self-indulgence and for decision-making: standardising measurements, understanding purpose and causes, designing disclosure systems, developing management systems, and scaling impact valuation. We describe one case of a cross-sector partnership that works towards a global measurement and valuation standard for disclosing positive and negative impacts of organisational activity and ultimately provides guidance on how these impacts can be integrated into business steering. Finally, we conclude with recommendations on how policymakers can contribute to this important and urgent global solution.

Introduction

Remarkable parallels can be drawn between the path towards a global low-carbon economy and the time before the Reformation in Europe: the growing demand for company disclosures of various societal and environmental impacts resembles the commercialization of indulgences in the late Middle Ages. Some churches famously traded indulgences by way of high fee payment for partial or full remission of their sins, comparable to debt payments. Subsequently, devote citizens paid exorbitant sums in exchange for certificates resulting in the growth of an extreme form of commercialization that quickly became open to abuse. As a reaction, a professor of theology and a priest, Martin Luther, formulated 95 theses against indulgences. His pamphlet criticised profiteering from these transactions and he allegedly pinned these papers on the portal of a church in a town south of Berlin. This event is believed to mark the beginning of the Reformation and, in turn, a fundamental change in economic and social structures in medieval Europe.1 Today, with social unrest around the world due to climate change and growing inequalities, we would like to set out five theses on how the global policy community can put an end to “sustainable self-indulgences” and move to decision-making that balances financial, environmental, and social value.

Our current landscape and the five theses

Transitions are always confusing: we left the old world order, but we have not yet found a new consensus. While we departed from a traditional world of local risks, we have not yet built the institutions, practices, and norms to tackle global challenges systematically. The confusion in global accounting policy is a symptom of this wider crisis of modernity. Global policy-making is highly fragmented and is lacking a moral discourse to coordinate business strategies, public policies, and civic activities. Recoupling the environment, society, and economy depends on how we understand value creation. Most analysts have framed problems as “externalities” to explain the negative impacts of corporate activity on society and the environment. Today, we observe a shift towards the measurement of impacts.

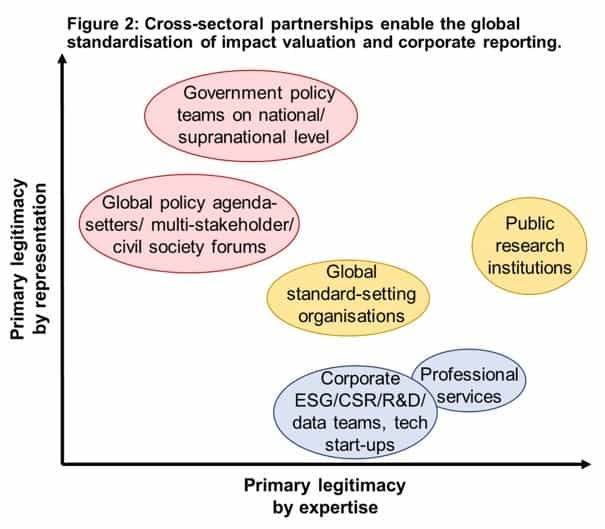

The fundamental question is not only one of technical measurability, but also one of legitimacy. This is a challenge common to all aspects of transnational governance. Which organisation should set global social-environmental measurement, accounting and reporting standards in the absence of a generally recognised holder of legitimacy? The graph below depicts six actors in the global field of impact valuation and corporate reporting. These organisations and groups of people are not yet sufficiently connected, but they have enormous potential to complement each other. Teams and networks across formal organisational boundaries are more difficult to create and maintain, but we believe it is necessary to create legitimacy for social-environmental reporting standards. Legitimacy can be ensured by different means, which include legitimacy by procedure, representation, and expertise.

The current landscape lacks connectivity between those actors whose primary legitimacy is based on representation – national governments, global policy forums – and those whose primary legitimacy emanates from expertise – standard-setters, research institutions, business teams, and professionals. Cross-sector partnerships may be one way to overcome this challenge, but they are hard to develop and maintain. Those types of inter-organisational collaborations connect a variety of actors beyond the traditional boundaries of professions, industries, public-private or hierarchies. They enable collaborations that draw on diverse sources of expertise and build on different types of legitimacy.

“Recoupling the environment, society, and economy depends on how we understand value creation.”

Thesis 1: Standardizing measurement

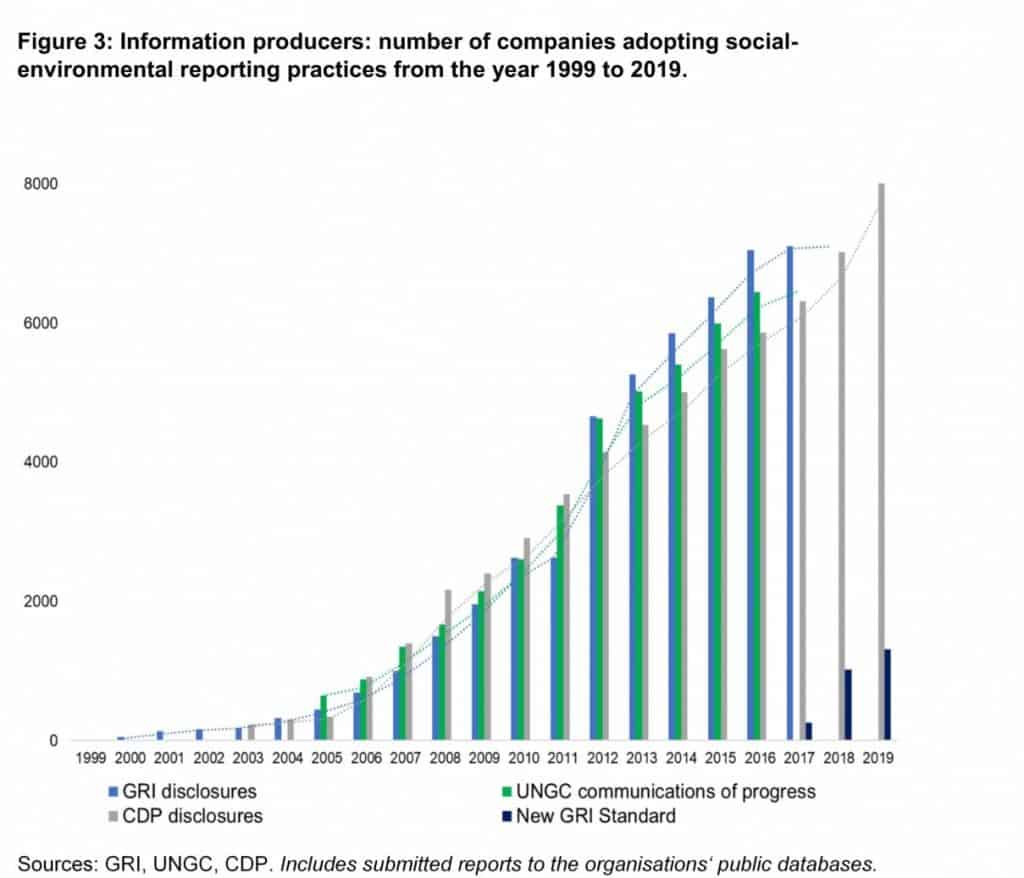

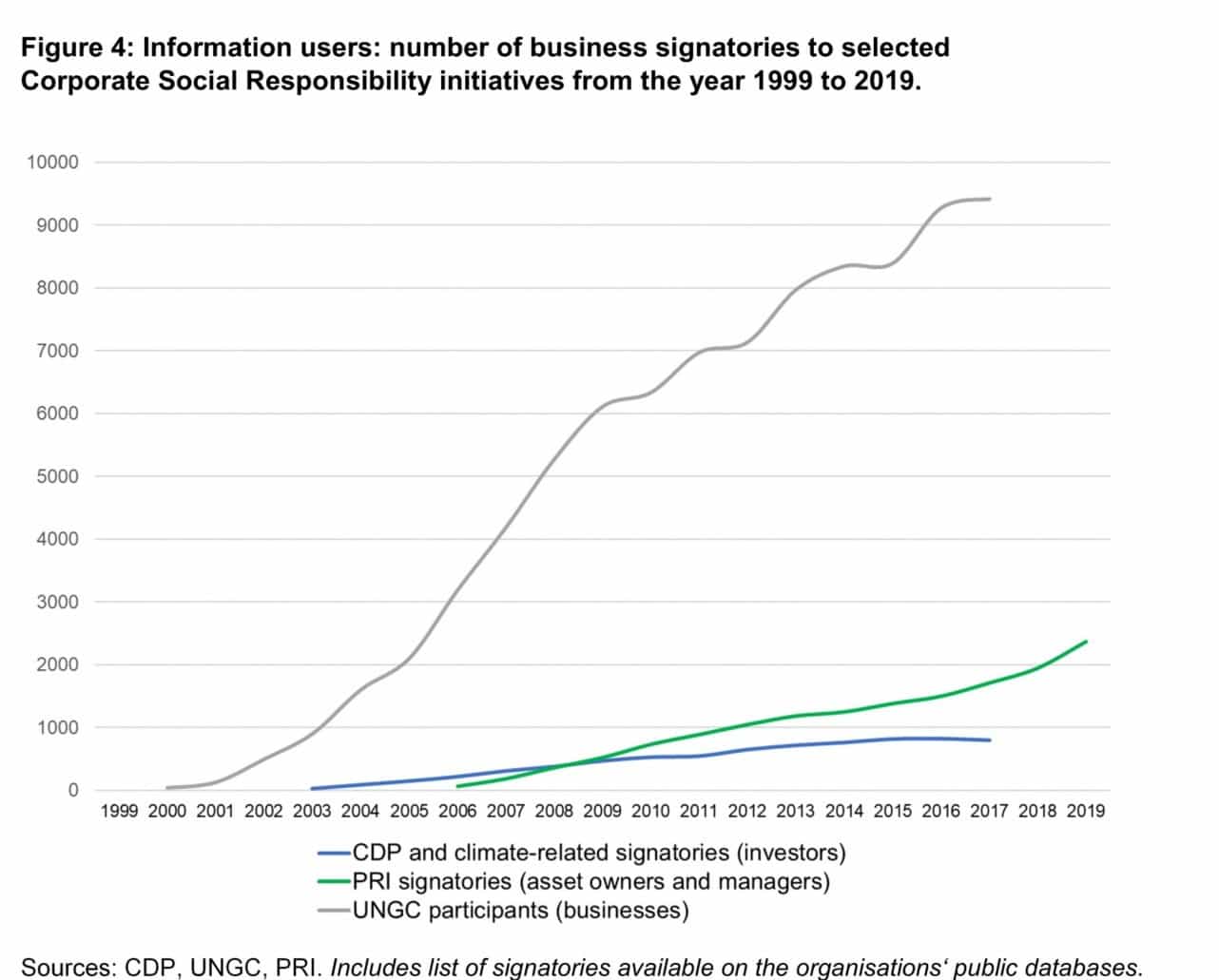

In the last twenty years, social-environmental reporting practices have increased globally. The early years saw moderate adoption reaching 1,000 reporting companies in 2007, followed by a sharp increase between 2007 and 2009 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Overall, the number of companies disclosing social-environmental reports significantly increased over the last two decades from less than a fifty to over 7,000 in the year 2017. We suggest that this trend will continue due to the relaunch of their standards by the pioneering Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the rise of standards by the newer Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) and the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) are thematic disclosures that are integrated into the more comprehensive conceptual frameworks of standard-setters.

However, there are signs of confusion and uncertainty. The ambiguity of the standards means that there is still no “shared language” around metrics that bridge social impact and financial performance for long-term thinking and decision-making. Until now, companies are both valued and managed based on accounting principles codified before the 1970s. The Sustainable Stock Exchanges Initiative with Johannesburg as a leader, the European Directive on Non-Financial Reporting (2014/95/EU) , the Europen Green Deal, the EU Taxonomy, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), and the Impact Management Project (IMP) are important actors who strengthen this necessary movement for standardisation.

Thesis 2: Understanding purpose and causes

We maintain that it is vital to begin with an understanding of the specific purpose of a corporate entity and the positive and negative impact of its organisational activity. Increasing evidence shows a link between high sustainability performance and financial performance. This relation is more prevalent when companies focus on social and environmental factors that are most relevant to their business model, thereby outperforming markets significantly.

Social-environmental reporting, in our view, fails when it is separated from strategy and decision-making. Firms are not producing comparable information, because materiality is essentially a judgment about which audience and perspective is prioritised. Understanding and articulating the purpose of the corporation focuses minds on business steering. Identifying the root causes of positive and negative impact are essential to building a framework that is comparable within and across sectors. An example of understanding cause-effect relations is the integrated report produced by SAP. The global enterprise software company statistically determined how metrics such as carbon emissions and employee engagement impact the operating profit of the company. While this approach allows social-environmental value to link with strategy, the obvious limitation is that each company takes a different approach in determining coefficients.

Thesis 3: Designing disclosure systems

When designing a disclosure system, it is important to balance specificity and openness simultaneously. The increase in signatories to the CDP, the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), and the UNGC indicate a growing demand for information by investors – asset owners and managers – and corporate leaders. The most common approach is to distinguish three dimensions – economic, environmental, and social – and, then to define key themes that categorise the different metrics. It is important to learn the lessons in the early days of environmental, social and governance (ESG) data, we need to deal with a variety of metrics, inconsistency of data, and different user perspectives. Paradoxically, companies that disclose more information than others suffer extreme variations in external ratings produced by different providers.

“The challenging part is not only to measure negative and positive impacts, but to express them in decision-useful ways.”

Specificity is achieved by focusing on information user cases, e.g. investment or procurement decisions. One indicator of the increasing demand among executives, asset managers, and asset owners are the initiatives they sign up for. The openness of disclosure systems is achieved when the information is accessible to scrutiny by the users. This means that the assumptions behind a certain reported number should be disclosed so that the users of this information can make sense of the data, and readjust it to their needs. Impact valuation would quantify the impacts on society, customers, employees, and the environment. This type of “prefinancial” information is translated into monetary units which, in turn, can be integrated into financial statements.

Thesis 4: Developing management systems

If a company is serious about its purpose, social-environmental information needs to be deeply embedded in corporate governance. Surprisingly, it is unclear who reads sustainability reports which are created in corporate social responsibility, finance departments, or a charitable foundation of the company. The data generated can be used in many ways: quarterly earnings calls, financial statements, and investor briefings. Even Larry Fink, CEO of the world’s largest asset manager Blackrock, has spoken out more strongly in favour of comparable disclosure, especially regarding climate risk.

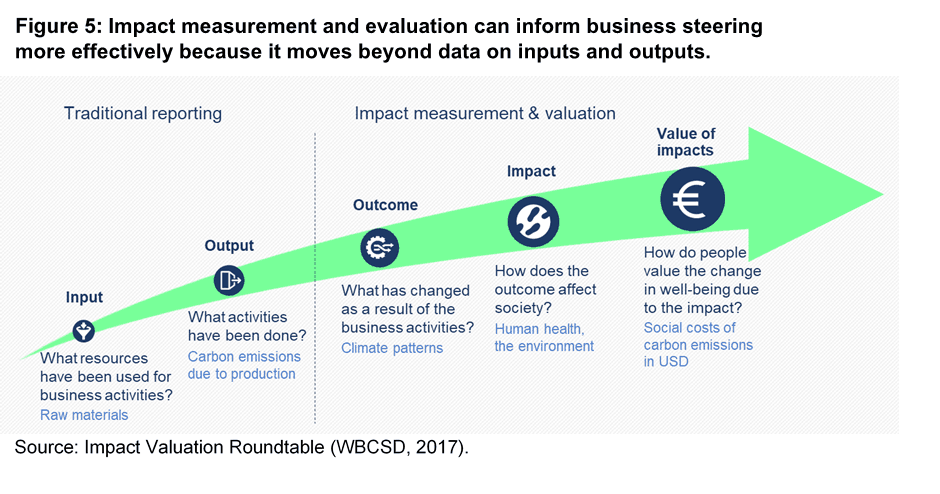

Traditional reporting is concerned with the resources that companies use (e.g. raw materials) and the activities (e.g. emissions from their production facilities). While those are necessary data, they are not sufficient to make informed business decisions about investment or procurement. The next step is to account for the impacts of those organisational activities. The challenging part is not only to measure negative and positive impacts, but also to express them in decision-useful ways. The methodology to do this – impact valuation – shifts the dial from mere reporting on inputs and outputs to evaluating impacts. This requires a monetisable model that links social-environmental metrics to co-efficients and, in turn, expressing impacts in financial terms for business decision-making and steering.

Thesis 5: Scaling impact valuation and corporate reporting standards

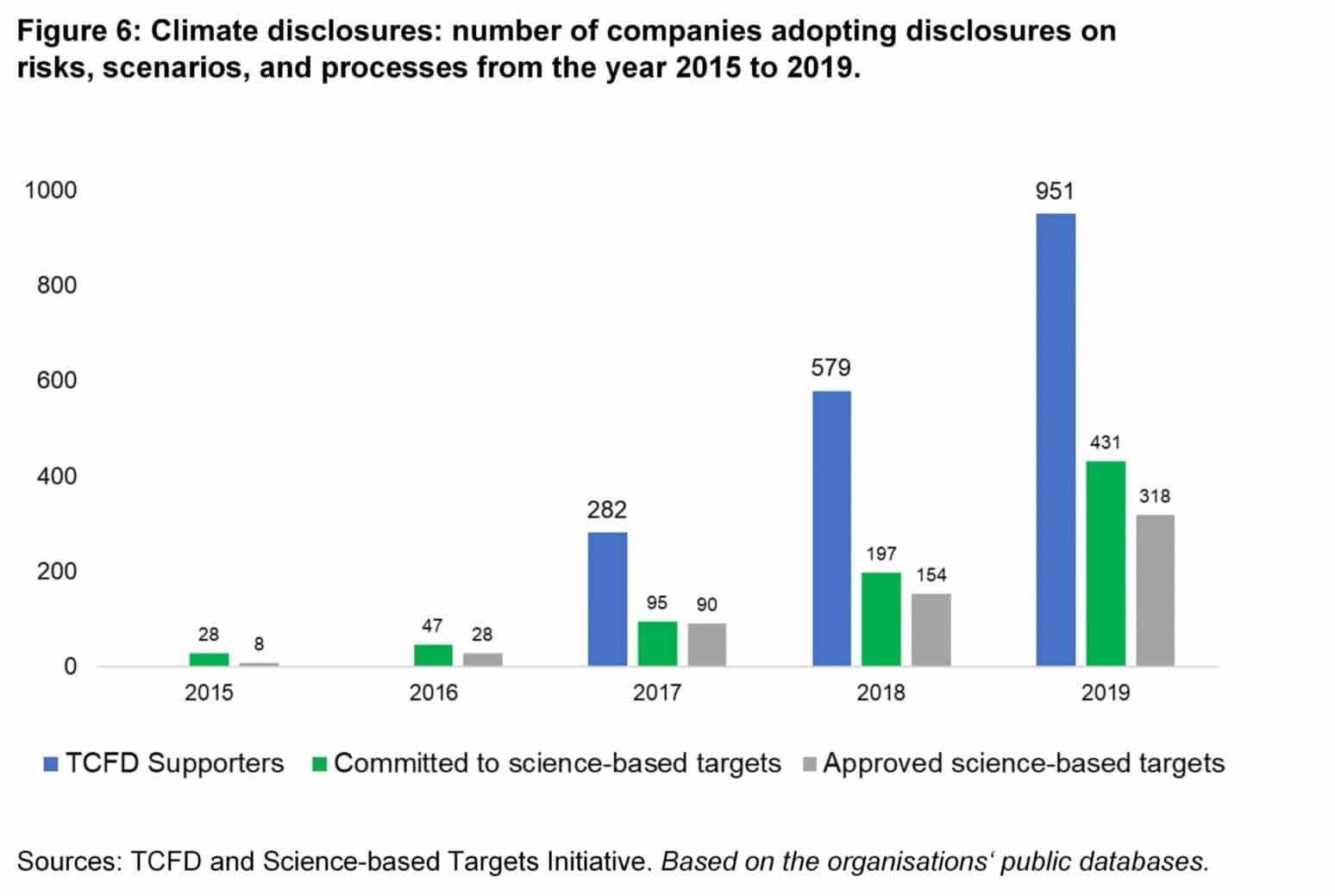

Impact measurement becomes scalable if it is “actionable and cost-effective”. One example of disclosures that scaled very quickly are the Recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). While they are not directly aimed at impact valuation, they show that business steering and corporate reporting are very much intertwined. Within four years, the adoption of TCFD has been almost doubling every year and is expected to significantly grow over 2020.

This scalability is due to three main reasons. First, TCFD are responding to the specific, pressing need to address climate change as a systemic risk for financial markets. Secondly, the disclosures focus on business decision-making in terms of processes, risks, and scenarios. Third, the TCFD is based on a concerted effort between national financial regulators, international organisations, standard-setters, and private initiatives, embedded within the major social-environmental reporting and other initiatives (GRI, SASB, IIRC, CDP, PRI). However, there is a fundamental limitation: without impact valuation and consensus about the measurements, decision-makers are left without clear and comparable ways of evaluating decision options.

The development of impact-weighted financial accounts is a viable approach but it requires legitimacy by expertise and representation to scale up and deep.19 One prime example for a cross-sector partnership is the value balancing alliance (VBA). The VBA was founded in 2019 and represents several large international companies, including BASF SE, Deutsche Bank AG, LafargeHolcim Ltd, Novartis International AG, Robert Bosch GmbH, SAP SE, SK Holdings, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings and Porsche AG. The alliance is supported by the four largest professional services networks – Deloitte, EY, KPMG, PwC – as well as by the OECD and the World Bank as advisors, and academics from leading academic institutions such as the University of Oxford and Harvard University. The alliance will play a key role in developing a green accounting standard for the European Union.

Conclusion: Toward cross-sector partnerships with the G20 for a global standard

In this article, we recalled the risk of self-indulgence in a fragmented landscape where social-environmental reporting is disconnected from decision-making. We formulated five theses against self-indulgence and for decision-making, and pinned them firmly on the global policy agenda. Finally, we make two recommendations to the global policy community: first, setting a global standard must be based on the core principles of value balancing: simplicity, transferability, comprehensiveness and scalability. Second, the global standard-setting process requires legitimacy by representation and expertise which is achieved through cross-sector partnerships. The value balancing alliance is a prime example for a cross-sector partnership that will play a key role in creating a green accounting standard in Europe. We can achieve the SDGs if we create together a global standard for impact measurement and valuation that will allow decision-makers to steer their businesses towards a just transition: environmental protection, low-carbon economy, sustainable economic growth, and social cohesion. There could not be a more appropriate time and place for the renaissance of purposeful business than in the birthplace of modern accounting – Italy in 2021. When it comes to sustainable business steering it is high time to turn the current reporting confusion into a global solution.

This article was written by Dennis West, Céline Bilolo, and Christian Heller for publication in the 2020 Edition of the Global Solutions Journal. The Global Solutions Journals provide a bridge between visions, recommendations and action.

The value balancing alliance was founded in June 2019 and represents large international companies, including BASF, Deutsche Bank, LafargeHolcim, Novartis International, Robert Bosch, SAP, SK Holdings, Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings and Porsche. The alliance is supported by Deloitte, EY, KPMG, PwC, the OECD as a policy advisor and leading academic institutions, such as the University of Oxford.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Solutions Initiative. This article was originally published in the 2020 Edition of the Global Solutions Journal. Download it here.