Women around the world face a wide array of economic realities, and live in varied social, cultural and political contexts. But they are also bound by common experiences which shape the ways that women interact with the economy differently from men. Efforts to advance the measurement of women’s economic empowerment must highlight the systemic barriers that women face using standard objective indicators and highlight the economic value of women’s unpaid work. Moreover, it is equally important to measure and account for subjective dimensions of ‘empowerment’ using proxy indicators that can be measured objectively (Buvinic, 2017).

This Policy Brief proposes governance frameworks and mechanisms for measuring women’s economic empowerment going beyond the standard measures of legal and pay equity. It makes recommendations outlining the need to work towards common definitions and targets for WEE, as well as key actions which public and private sector actors can begin to implement immediately to have a positive impact on WEE and build robust monitoring and evaluation systems to track objective and subjective aspects of WEE. In addition, this brief outlines specific areas of measurement of WEE for both public and private sectors, recognizing that countries should measure their level of progress against their own starting points rather than comparing against other countries.

Challenge

MEASURING WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT

Women’s economic empowerment (WEE) is women’s independent ability to participate in, contribute to and make economic decisions which have the potential for economic advancement (Golla et al., 2011; OECD, 2011). With the growing recognition that gender equality promotes economic stability and growth, under the respective 2018 Presidencies of Canada and Argentina, members of the G7 and G20 committed to an increased focus on gender economic equity. This commitment is largely driven by the growing body of evidence that points to WEE boosting economic growth and productivity, enabling greater equality of overall income distribution, supporting higher corporate profits, increasing economic resilience, supporting bank stability and contributing to other development outcomes such as improved health for women and children (IMF 2018). However, as noted by the IMF (2018) there is much work to be done since, “Despite progress, women and men do not have the same opportunities to participate in economic activity, and when women do participate, they do not receive the same recognition, wages, or benefits as men.”

Moreover, based on the World Economic Forum’s estimates, at the current rate of progress it will take 217 years to close the overall global gender gap in female labor force participation and equal economic opportunities.

This brief recognizes that issues of WEE are complex, requiring cultural and contextual sensitivity, and recognition of the fact that women do not constitute a homogenous group and, as a consequence, ‘one size’ economic policies, initiatives and measures do not ‘fit all.’ Moreover, although empowerment itself is transversal across economic, political, social and psychological domains (Fox and Romero, 2016) and is often perceived at the level of the individual, it can and should be measured at the household and community levels as well to capture the ripple effects of WEE (Buvinic, 2017; Scott, 2016). Hence the challenge in defining and measuring the empowerment of women as economic actors is to establish a common framework that works at different levels of analyses, given variations in context.

Challenge 1: Accountability and impact on WEE will look different in different contexts

To advance WEE, multiple stakeholders must assume and be held accountable for impact through measurement and corresponding governance mechanisms. Accountability and impact on WEE will look different for the public and private sectors, for economies with large informal sectors versus those that are predominantly formalized, those that rely on agriculture versus those that are driven by the services or industry. Varied cultural, social and political contexts also make setting goals that enable cross-country comparability a challenge. This brief takes the approach of outlining broad policy areas for major stakeholders (public and private sectors) that should be considered to ensure that WEE is achieved and has the desired impact on labour (wage and salaried employment), farming and entrepreneurship, distribution of unpaid work, and digital and financial equity.

Challenge 2: Paucity and quality of data compromise measurability and accountability

Interventions to improve WEE may be directed at one or a number of the following: direct outcomes such as knowledge, skills or acquiring productive assets; intermediate outcomes such as changes in women’s decision-making roles in their businesses/ farms; or final outcomes such as business income, employment, asset ownership, gender norms, and women’s self-confidence (Buvinic and Furst-Nichols, 2015). Some indicators have more established methodologies than others however.

Much of the focus in measurement of WEE to date has been on economic outcomes rather than the process through which women become economically empowered (Buvinic, 2017). In addition, even for measures that have been widely agreed, data collection to support these measures is low and there are significant gaps on issues such as occupational safety and health (OSH) conditions. As a result, related policy and decision making has been correspondingly weak. Moreover, as the world of work evolves, coverage and measurement issues that already existed may become exacerbated and new gaps in data on women’s economic lives may emerge. Specific data challenges include:

• Data on individuals in informal jobs (both as employees and in selfemployment), which in some developing countries accounts for the majority of employment, is particularly difficult to capture. As women are more likely than men to be in the most vulnerable informal jobs (ILO 2018b), data on this group is crucial to ensure that countries can move towards formalization in a gender-sensitive way.

• Data on work, pay and working conditions at an individual level, i.e. pay or profit, is also low in developing country contexts.

• The conceptualization of the household has to be de-constructed to better estimate women’s contribution to the economy since current concepts of the household makes women invisible.

• WEE is shaped by both paid and unpaid work, the majority of which is done by women. However, coverage of data on unpaid work is currently low and failure to deal with this issue hampers our understanding of WEE (Scott 2016) at the national and sub-national levels.

• Measurement of access to and ownership of assets, including physical assets like land, as well as notional assets such as financial and digital assets, for men and women separately is also a challenge that must be met.

Challenge 3 Governance Mechanisms and Measurement of Progress:

a. Public Sector Mechanisms and measurements of progress need to take account of the public sector’s role in WEE on three levels: public sector as employer; public sector as shaper and implementer of policy that can enhance or slow WEE; and public sector as compiler of official statistics on WEE and as user of these statistics to define and monitor progress in public policies regarding WEE. As noted by Thomas et al. (2018): “The collection and dissemination of robust and consistent sex-disaggregated economic and social data to inform and support evidence-based policy making poses a significant challenge. Therefore, the integration and implementation of a gender focus on data collection, disaggregation, analysis and publication all demographic, social and economic statistics are critical for designing, implementing and monitoring gender-informed policies”.

b. Private Sector Accountability mechanisms are challenging in the private sector as they must deal with the private sector’s role as employers, i.e. directly influencing WEE, but also in terms of the goods and services they produce and how these directly or indirectly impact WEE, and the data they generate that can be useful to measure and monitor WEE. Access to and sharing of meaningful data on WEE is a key challenge for private sector organizations which the proposals below are designed to address.

Proposal

Proposal 1 Agree a definition and framework of women’s economic empowerment (WEE) to facilitate the setting of clear goals and targets for labor, farming and entrepreneurship, digital and financial equity

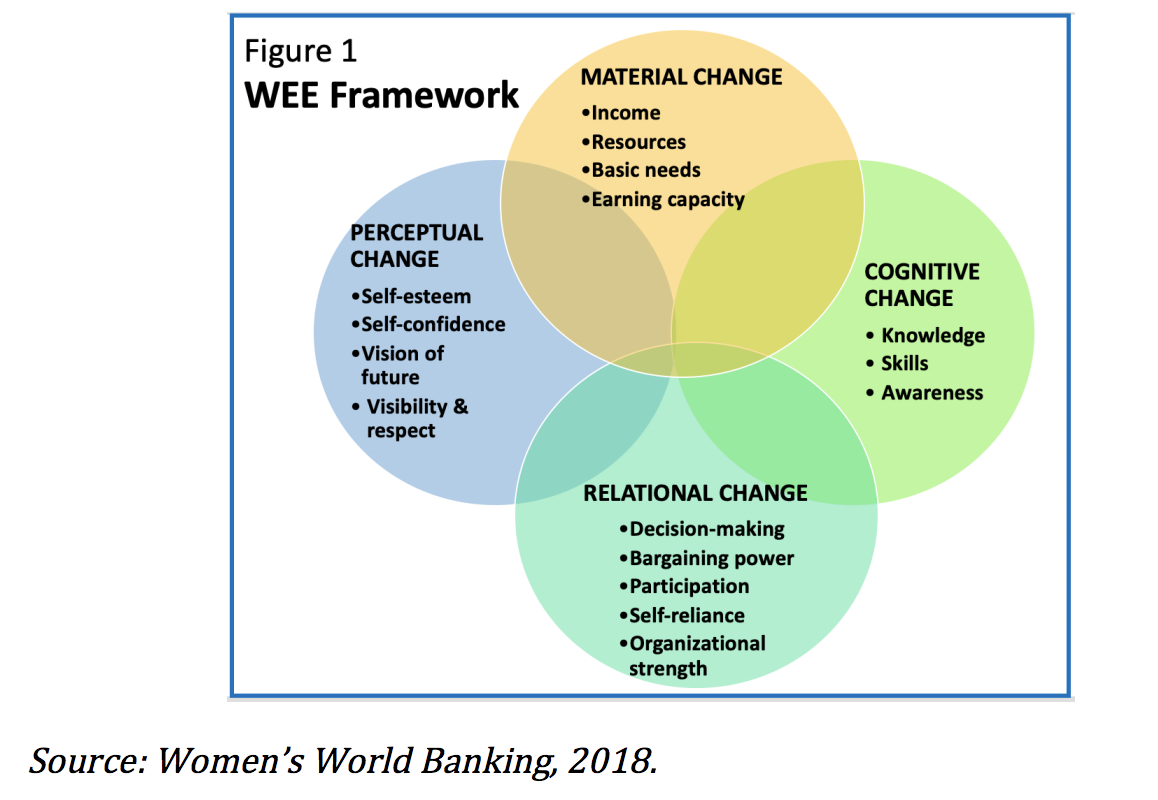

A number of frameworks for and definitions of WEE have been devised, including the framework shown in Figure 1 below. There is general agreement that key areas of focus for the measurement of WEE include (a) women’s economic outcomes, e.g. labour market outcomes; and (b) subjective aspects such as increases in women’s agency. However, a universally adopted definition/ framework has not been arrived at. The first proposal therefore, is for countries to work together to establish a common definition and measurement framework on WEE process and outcomes that will apply across cultures (Scott 2016). This would enable agreement on goals and targets.

Proposal 2 Strengthen the public sector’s direct (policy-making and budgeting) and indirect (data compilation) role in bringing about WEE

Accountability mechanisms to hold public sector actors accountable as employers, policy makers, and statistics compilers, will necessarily involve civil society actors, self-reporting between government arms, and the electorate prioritizing and following activities on WEE.

With regard to the public sector’s policymaking and implementing role, we recommend the following (Thomas, et al, 2018):

• Design and implement policy processes to systematically include a gender focus on the determinants of gender inequities by requiring, implementing, and resourcing impact assessments to assure inclusivity, transparency, consistency and accountability.

• Implement gender budgeting at national and sub-national levels, placing implementation and accountability at the political center of fiscal decision-making on the ministries of finance.

Recognizing that data constitute essential inputs for quality policy design, benchmarking and measuring progress on implementation, and accountability (Thomas, et al, 2018), we recommend that governments take the following steps to improve WEE data availability and quality:

• Provide resources to national statistical systems to close gender data gaps. • Give priority to the following categories of statistical data collection: labor, digital and financial inclusion; measurement of unpaid work; participation in the agricultural and agri-business sectors; and, access to care support and social protection.

• Develop robust reporting and communication mechanisms to share this information with stakeholders for analysis, policy design, impact assessments, monitoring and evaluation, and advocacy.

Supporting gender-based research initiatives such as the work of the Global Women’s Entrepreneurship Policy research group, which examines existing policies on a comparative basis across countries using a gender lens, is also recommended (Henry et al., 2017). Recommendations under proposal 3 below also pertain to the public sector’s role in collecting data from the private sector and as employers in their own right.

Proposal 3 Build robust public-private data sharing mechanisms to enable monitoring and evaluation of key areas of WEE in employment and enterprise and farming.

Employment (wage and salaried). Standardized measures of rank and pay should be mandated for reporting on an annual basis.

• Pay, in particular, should be reported according to a set formula, such as was done by the U.K. government in spring of 2018, in order that differences cannot be hidden and sources of pay inequity are made clear.

• A national survey, similar to the one conducted by the World Economic Forum’s 2010 Corporate Gender Gap Report, should be undertaken to monitor availability of supportive programs, such as mentoring or maternity leave, as well as perceptions of barriers and women’s career progress within firms.

•Public disclosure of board and senior management composition by gender should be mandated.

• Governments should collect data from small and medium firms, not just from large corporations, as the majority of every population is employed by firms with fewer than 250 employees.

• These data will only capture individuals employed in the formal sector however. Individuals in the informal sector or working informally in formal sector jobs and the ‘gig economy’ should be enumerated through improved labour force surveys, in line with new guidance from the ILO (ILO 2018a).

Enterprise and Farming.

• Existing data collection on enterprise should include a gender marker to identify female owned or operated businesses, with a standardized definition so that cross-national comparisons can be made.

• Similarly, female-owned or operated farms should be identified and measured. Equally important is to better measure women’s participation in farming, both subsistence production and cash cropping (UNFAO 2017; ILO 2018a).

• Existing laws barring collection of gender data by banks and other financial sector providers should be lifted where they are in operation, and

• Sex-disaggregated financial data on account ownership and usage, credit levels and interest, savings, insurance, pensions etc. should be reported regularly in an anonymized format to financial regulators in-country and to the IMF Financial Access Survey.

• Sex-disaggregated digital data on ownership and use of digital communication technologies and on mobile banking should be encouraged and made available on an anonymized basis to monitor digital and financial inclusion.

Mechanisms of accountability in the private sector require strengthening. Often, unless a regulation gives government bodies the ability to mandate information, voluntary or self-reporting mechanisms are used. However, voluntary and self-reporting schemes are not sufficient. In some cases these schemes are used to ward off mandatory reporting and limit oversight. Public private sector collaborations should be pursued to increase access to and mine private sector data for public good WEE purposes.

CONCLUSION

Women’s economic empowerment (WEE) is a complex issue. It is influenced by myriad social, cultural and political factors, and will always be a contextdependent phenomenon. This Policy Brief has outlined the key challenges associated with the measurement of WEE and has offered a number of proposals for its enhancement. However, the success of these proposals is contingent on the following: 1. Acknowledgment and understanding of both the systemic barriers and contextual differences involved in WEE; 2. Concerted efforts to address the data gaps; 3. Application of a gender lens to all areas of economic empowerment, including policies and support initiatives designed to promote same; and 4. Commitment from all stakeholders to play their part in enhancing WEE globally. Finally, meeting the measurement challenge to assess not only the outcomes but the process of WEE as a means to WEE outcomes and a valued end in itself, should also be prioritized.

References

• Buvinic, M. 2017. Measuring Women’s Economic Empowerment: Overview. Available at: https://www.womeneconroadmap.org/sites/default/files/Measures_Ov erview.pdf.

• Buvinic, M. and Furst-Nichols, R. 2015. Measuring women’s economic empowerment: companion to a roadmap for promoting women’s economic empowerment. Available at: https://www.womeneconroadmap.org/sites/default/files/Measuring% 20Womens%20Econ%20Emp_FINAL_06_09_15.pdf

• Fox, L., and Romero, C. 2016. In the mind, the household, or the market? Concepts and measurements of women’s economic empowerment. Available at: https://www.womeneconroadmap.org/sites/default/files/Louise%20Fo x%20-%20Measuring%20subjective%20empowerment%20v3-2.pdf

• Golla, A. et al, 2011. Understanding and Measuring Women’s Economic Empowerment: Definition, Framework and Indicators. Washington, DC: ICRW. Available at: https://www.icrw.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/10/Understanding-measuring-womenseconomic-empowerment.pdf

• Henry, C., Orser, B., Coleman, S., Foss, L. & the Global WEP Research Team. 2017. Women’s Entrepreneurship Policy: A 13 nation cross country comparison. International Journal of Gender & Entrepreneurship, 9(3): 206-228.

• ILO 2018a, Main findings from the ILO LFS Pilot Studies, Available at https://www.ilo.org/stat/Areasofwork/Standards/lfs/WCMS_627815/l ang–en/index.htm

• ILO, 2018b, Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A statistical picture. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/— dgreports/—dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_626831.pdf

• IMF, 2018. Pursuing Women’s Economic Empowerment. Washington, DC: IMF. Also available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/PolicyPapers/Issues/2018/05/31/pp053118pursuing-womens-economic-empowerment

• IMF. Financial Access Survey. Available at https://data.imf.org/?sk=E5DCAB7E-A5CA-4892-A6EA-598B5463A34C.

• Kochhar, K., S. Jain-Chandra, M. Newiak, 2017. Women, Work, and Economic Growth: Leveling the Playing Field. Washington, DC: IMF.

• OECD, 2011. Women’s Economic Empowerment Issues Paper. Paris: OECD. Also available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/PolicyPapers/Issues/2018/05/31/pp053118pursuing-womens-economicempowerment

• Scott,L. 2016. Advisory note on measures: women’s economic empowerment. Available at https://www.doublexeconomy.com/wpcontent/uploads/2018/11/advisory-note-on-measures-final2016.pdf.

• Thomas, M. Novión, C.C. et al. 2018 “Gender mainstreaming: a strategic approach”, (T20 Policy Brief), Global Solutions Journal, 1[2], 155-173.

• UNFAO, 2017. Guidelines for collecting data for sex-disaggregated and gender-specific indicators in national agricultural surveys. Available at: https://gsars.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/GENDERFINAL_Guideline_May2017-Completo-10-1.pdf • World Economic Forum, 2010. The Global Gender Gap Report. Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GenderGap_Report_2010.pdf