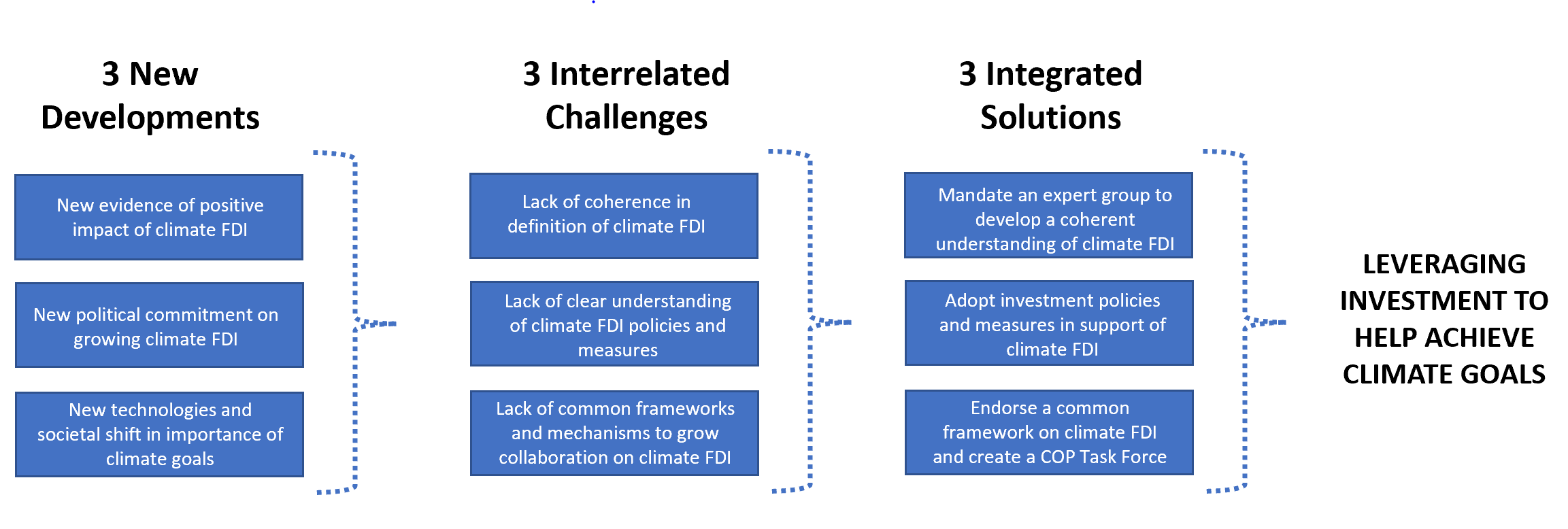

Certain foreign direct investment (FDI) can help achieve environmental goals, known as ‘green FDI’; a subset that can help achieve climate goals is known as ‘climate FDI’. Both governments and firms seek to grow climate FDI, but challenges remain: (1) lack of clear understanding of what constitutes climate FDI; (2) lack of awareness and adoption of specific policies and measures; and (3) lack of common frameworks and mechanisms for collaboration on climate FDI. The policy brief thus suggests: (1) to mandate an expert group to develop a common understanding of climate FDI; (2) to consider adopting 15 specific, targeted policies and measures in support of climate FDI; and (3) to create a COP Task Force on Climate Investment Policy and endorse new frameworks that encourage investors to increase climate FDI.

Challenge

Climate change represents one of the greatest threats the world faces today. The question is, how can foreign direct investment (FDI) help achieve climate action? Answering this question requires understanding the following three interconnected challenges.

First, there is a lack of clear and consistent understanding of what is climate FDI. This is holding back both FDI’s potential to contribute to climate goals as well as cooperation between public and private actors on supporting, and thus growing, climate FDI.

Second, there is a lack of awareness of cutting-edge investment policies and measures that can help incentivize, facilitate, protect, and retain climate FDI. While governments and firms have rallied around the importance of growing climate investments, the pathways and tools to do so are not yet well understood, and thus their uptake has been limited.

Third, there is a lack of coordination and cooperation between public and private actors on stimulating and scaling climate FDI—as well as between governments in different jurisdictions—resulting in below potential climate FDI flows. Standing mechanisms and agreed frameworks are needed to facilitate cooperation and move from piece-meal to generalized efforts.

Reshaping these challenges is the recent war in Ukraine, which has caused an energy price shock that in the short term may cause more investment in fossil fuel-based energy generation, though in the medium term is expected to boost even further investment in renewables. However, the war is also increasing investment in the defence industry, which is generally carbon intensive.

Thankfully, there are three new, interrelated factors that create the opportunity for the G20 to help address these challenges and in so doing both drive and scale climate FDI.

First, there is new evidence that green FDI projects lead to a shift in green behaviour across the parent firm, in subsidiaries and by other domestic businesses through spillovers (Amendolagine et al., 2021; OECD, 2021). This motivates the increase of such investment, specifically the subset geared to climate actions, given its broad benefits beyond the specific investment project.

Second, there is new political commitment to implement the Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) through investment: in the Glasgow Climate Pact, Parties agreed “to further scale up investments in climate action” (UN, 2021); at the same time, leading business launched the First Movers Coalition, committing to buying zero-emission goods and services and building clean supply chains (Brende 2021; Whiting 2021). This momentum has translated into climate FDI project value in 2021 twice the pre-pandemic level of 2019 (UNCTAD, 2022).

Third, there is rapid growth in new technologies that can help achieve climate goals, as well as growth in society’s desire for climate action; however, enabling policies, regulation and investment measures have not kept up with these changes, holding back FDI in support of climate goals (Stephenson et al., 2021). Developing or updating policies, regulations and measures can thus help unlock flows of climate FDI.

Finally, new data are available to guide and prioritize these efforts. The data indicate that globally climate FDI is overwhelmingly concentrated in mitigation versus adaptation (95 percent of projects are in mitigation, only 5 percent in adaptation), with the vast majority in renewables (70 percent of all climate FDI in 2021, mostly in solar and wind)[2], and to a lesser extent in energy efficiency (UNCTAD, 2022). When zooming into developing countries, the share of climate FDI in adaptation grows, but not by much (88 percent of projects are in mitigation, 12 percent in adaptation).[3]

Proposal

The policy brief lays out three proposals to help address these challenges, as summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1: Overview of developments, challenges, and solutions to grow climate FDI

Proposal 1. Mandate an expert group to agree on a definition of climate FDI

The G20 should mandate an expert group to agree on a clear and common understanding of climate FDI.[4] There is currently significant divergence and confusion in the definition, implementation, and support of FDI to achieve climate goals, holding back financing of climate FDI as well as regulatory support (Johnson, 2017; OECD, 2015; UNCTAD 2008, 2010, 2022). Clarity and coherence are necessary for government-to-government, as well as government-to-business, cooperation on growing investment for climate goals.

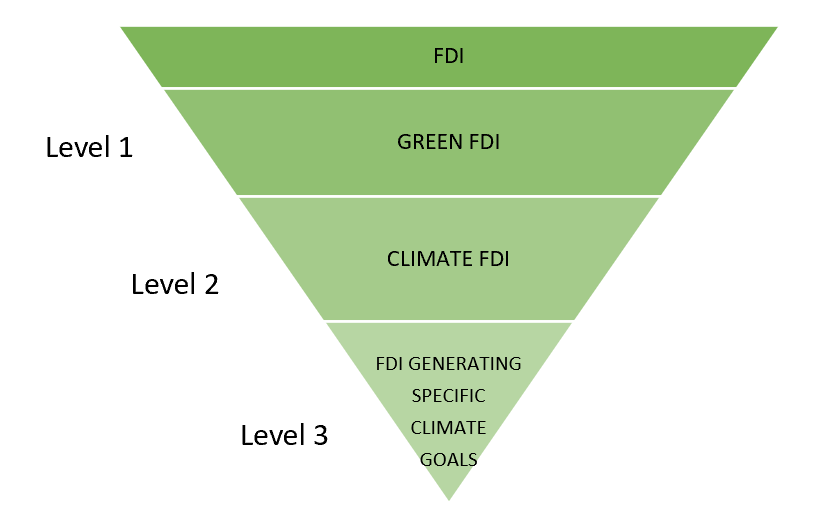

Figure 2: Three-level conceptual framework to understand climate FDI

To help inform and guide this exercise, this policy brief posits a three-level conceptual framework to help understand climate FDI: Within the universe of FDI, certain FDI can help achieve environmental goals, known as green FDI, at level 1 (Golub et al., 2011; Johnson, 2017; Sauvant et al., 2021; UNCTAD, 2016). Within green FDI, a subset of FDI can help climate goals, or climate FDI, at level 2. Within climate FDI, certain FDI can further help achieve specific climate goals, for instance mitigation or adaptation, at level 3 (UNCTAD, 2022).[5]

Importantly, this conceptual framework suggests that climate FDI can be determined on the basis of investment impact, rather than the traditional methodology of defining FDI based on investor motivation (Dunning, 1982). In other words, climate FDI is any investment that leads to measurable improvement in climate conditions in a host economy, regardless of sector or activity.

This is why it is also helpful to think of climate FDI in three conceptual pillars: (1) FDI into sectors that are especially important for the climate (e.g., water management[6]); (2) FDI that helps improve the climate impact of any sector (e.g., automobile manufacturing lowering emissions); and (3) FDI that should exit certain industries (e.g., polluting fossil fuels).[7]

Figure 3. Three pillars of action to grow climate FDI

Source: Abhishek Saurav, Investment Facilitation Commentary Group presentation, 12 April 2022

Proposal 2. Adopt climate FDI policies and measures

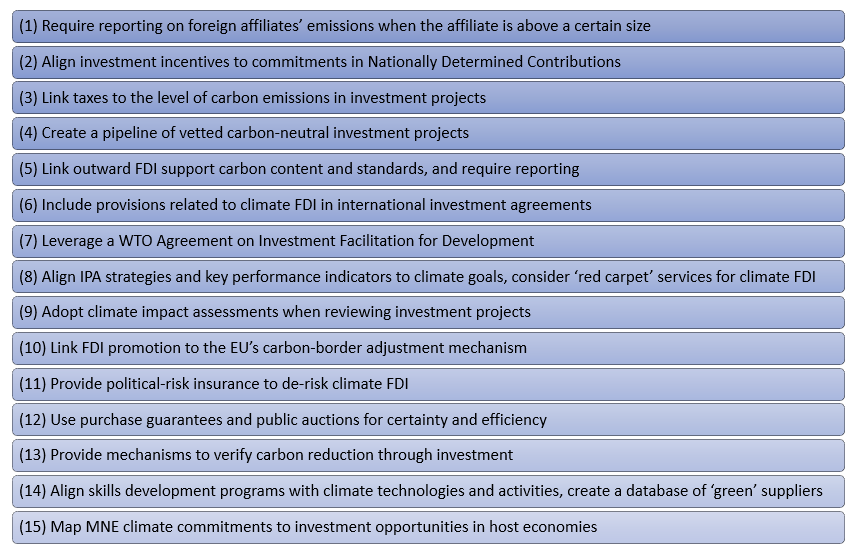

G20 economies should adopt cutting-edge policies and measures to support climate FDI. These are measures specifically designed to attract, facilitate, protect, and retain climate FDI across the investment lifecycle (Sauvant et al., 2021; WBG 2020). What are these cutting-edge policies and measures? Below are 15 suggestions. G20 policymakers can both individually consider adopting them, and also use them to foster common G20 steps to help grow FDI for climate action.

1. Require reporting on foreign affiliates’ emissions when the affiliate is above a certain size

Information on emissions is a sine qua non of effective climate action, with society able to allocate capital according to societal preferences, in this case allocating greater investment to carbon neutral projects. However, such reporting may be too burdensome for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) venturing abroad, in terms of the cost of reporting relative to their human and financial resources, so the requirement should only kick in for firms above a certain size.

2. Align investment incentives to commitments in Nationally Determined Contributions

Policymakers can align investment incentives—both financial and non-financial—to climate commitments laid out in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). In other words, if an investment is aligned with or helps to achieve those commitments, then it can receive greater support. The beauty of this measure is that the incentives can evolve as NDCs evolve, given a natural evolution in climate context and thus climate priorities within an economy.

3. Link taxes to the level of carbon emissions in investment projects

An additional, complementary, and very practical way to incentivize climate FDI is by linking the rate of taxes to the level of carbon emissions in an investment project: the lower the emissions, the lower the taxes.

4. Create a pipeline of vetted carbon-neutral investment projects

There are mixed views as to whether pipelines of proposed investment projects are taken seriously by investors, given that they need to carry out their own due diligence and financial modelling. However, in markets with imperfect information and perhaps relatively weak institutions, government endorsement of a project can de-risk that project, given that it has received official support. At the same time, an independent consulting firm could vet financial estimates, providing additional information that could facilitate investor interest.

5. Link outward FDI support to carbon content and standards, and require reporting

There can often be a difference in the level of capacity and also standards between home and host economies in terms of climate action, especially when development levels vary. As a result, home governments can play an important role to facilitate outward FDI that is carbon neutral or carbon negative[8] by only providing certain home-country measures in support of outward FDI when that investment is carbon neutral or carbon negative, and when it follows relevant home-country environmental standards. In addition, home governments can also require reporting by their firms on outward FDI carbon content of projects above a certain size, complementary to item (1) above.

6. Include provisions related to climate FDI in international investment agreements

Including climate FDI provisions in international investment agreements (IIAs) can help to protect, promote, facilitate, or otherwise support FDI that helps lower carbon, is carbon-neutral, or is carbon negative. This provides a very clear mechanism to encourage such investment, as it is part of the legal framework, thereby providing both greater clarity and certainty to investors, as well as stipulating consequences and recourse should the provision not be followed.

7. Leverage a WTO Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development

The future WTO Agreement on Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) can act as a key resource to facilitate climate FDI in several ways. First, it can actively facilitate such investment by including provisions that target climate FDI. Second, it can be implemented in a way that focuses on facilitating climate FDI, even if there are no explicit provisions in the text related to climate FDI or if only the preamble mentions the importance of tackling climate change through investment facilitation. Third, the committees and technical assistance that are expected to be part of the Agreement and its implementation can work on experience-sharing and good-practice exchange, as well as capacity building, on facilitating climate FDI.

8. Align IPA strategies and key performance indicators to climate goals, and consider “red carpet” services for climate FDI

As the adage goes, what gets measured gets done, and so including climate goals in the strategies and especially key performance indicators (KPIs) of investment promotion agencies (IPAs) will help orient efforts to delivering climate FDI results. Such KPIs can take the form of greater climate FDI flows, greater number of climate FDI projects, or increased climate FDI commitments by investors. A recent survey focused on OECD economies found that less than 40 percent of IPAs prioritised investments to mitigate climate change, indicating the clear need to include such KPIs (OECD, 2021). Relatedly, IPAs can adopt “red carpet” services for climate FDI, such as faster approvals, dedicated aftercare, etc.

9. Adopt climate impact assessments when reviewing investment projects

Investment authorities are increasingly using environmental impact assessments when determining whether or not to provide approval, support, or incentives, though the use of such assessments needs to continue to grow. Importantly, climate considerations should be part of environmental impact assessments, in other words there should be a climate impact component to the assessment.

10. Link FDI promotion to the EU’s carbon-border adjustment mechanism

The European Union carbon-border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) aims to levy a carbon tax on goods produced outside of the EU based on their carbon content, just as the EU does for goods produced within the EU, with the aim to create equal costs for production based on carbon content. Investment promotion efforts can use CBAM to attract climate FDI by calculating how much savings a specific project could accrue in terms of carbon tax not being levied if the FDI project produces the good at a lower carbon level relative to the good having been produced abroad with a higher carbon content. This savings estimate can be used as a promotion mechanism to engage firms to consider climate FDI projects in the EU, or climate FDI projects outside of the EU where the good or service produced by the investment project is intended for export, at least in part, to the EU market. Down the road, if other jurisdictions also adopt CBAMs, the same logic and action would apply and could be used.

11. Provide political-risk insurance to de-risk climate FDI

Investors often cite risk as one of the main reasons they are reluctant to undertake FDI in emerging and developing markets. By providing insurance instruments specifically designed to address political risk related to climate FDI, this could help increase investor comfort and interest. This is particularly important for climate FDI given that climate issues have been a highly politicized topic, and so the political risk—for instance when governments change—may be considerable. It is worth noting that individual countries need not provide such political risk-insurance themselves if they are a member of the World Bank Group’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which could be mandated to provide climate FDI-specific political risk insurance.

12. Use purchase guarantees and public auctions for certainty and efficiency

Investors report that a key measure to increase climate FDI are purchase guarantees of clean energy at a certain price, following an investment to generate such clean energy. The same could apply to purchase guarantees of goods or services produced with lower carbon content. In other words, if a certain good is produced with a certain carbon content through an investment, the government (or other actors) could provide a purchase guarantee to purchase the good at a certain price. This creates certainty in the investor’s eyes and thus, once again, de-risks the investment. In addition, public auctions can be used as a mechanism to ensure that tenders for investment in low-carbon activities, especially the provision of utilities, are done efficiently at the least possible cost.

13. Provide mechanisms to verify carbon reduction through investment

Investors report that one of the challenges to growing climate FDI is that the carbon reduction brought about by such investment is not easily measured and therefore credited, either economically or politically. Specialized organizations or firms could help to calculate the carbon abatement of specific investment projects, and help link incentives, approvals, and other policies and measures accordingly.

14. Align skills development programs with climate technology and create a database of “green” suppliers

Investors also report that skills can be a critical determinant regarding investment location decision-making. In addition, when it comes to deciding what kinds of technologies to include in FDI projects, the level of skills available in the host economy will help determine whether the most advanced technologies are selected or not. As a result, host governments should partner with firms and with academic and training institutions to provide skills-development programs that impart climate-related skills to use corresponding technology and perform relevant activities. This can also help create a list of domestic firms that operate in a climate-friendly manner, facilitating FDI that is looking to contract with such suppliers. These suppliers can then be listed in a database that recognizes climate commitments, such as the one Cambodia created named the “Supplier Database with Sustainability Dimensions” or SD2.[9]

15. Map MNE climate commitments to investment opportunities in host economies

A final innovative measure to facilitate climate FDI is to map multinational enterprises’ (MNEs) climate commitments to investment opportunities in host economies, which would help firms achieve and deliver on these commitments. This would contribute to overcoming information gaps and also provide pathways to achieving publicly announced objectives. Both firms and host economies would benefit from helping to “nest” climate commitments and objectives in real-world investment projects, a type of actionable roadmap to deliver climate commitments through investments.

Figure 4: 15 specific, targeted policies and measures to support climate FDI

Further development of IIAs/WTO IFD Agreement

Given the importance of IIAs and the WTO IFD Agreement as instruments to drive and grow climate FDI, the following text provides a template for how to integrate climate FDI into these agreements:

Each Party shall encourage the facilitation of climate foreign direct investment that assists the Parties to become carbon neutral, including by promoting renewable energy, energy efficient investments and appropriate technologies, and taking other measures that help the transition to a carbon-neutral, sustainable, and climate-resilient economy.[10]

It would be important to decide whether the provision should cover all environmental goals or specifically climate goals, and if the latter, carbon neutrality or, even more ambitiously, also support investment that is carbon negative.

There are a number of additional provisions that could be included in IIAs in support of climate goals (Stephenson and Vieira Martins, 2022). For instance:

- The inclusion of carve-outs for climate-related public policies when it comes to Investor-State Dispute Settlement (or exemptions to specific provisions, such as for climate-related public policies from provisions on Indirect Expropriation or Fair and Equitable Treatment)

- The inclusion of Corporate Social Responsibility Clauses mentioning the need for investors to pursue climate goals in their activities (due diligence requirements)

- The inclusion of provisions encouraging the adoption of measures to promote and facilitate climate FDI

For this last point, IIAs could provide examples of measures but mention that these examples are non-exhaustive, given that our understanding and identification of climate FDI measures is still nascent and growing (Stephenson and Vieira Martins, 2022).

Proposal 3. Support new initiatives for investment and climate goals

Proposal 3a. Create a COP Taskforce on Climate Investment Policy

G20 economies should call for a COP Taskforce on Climate Investment Policy, to create a standing mechanism for dialogue and cooperation on climate FDI. This would facilitate collaboration between public and private actors on climate FDI. It would also be complementary to the existing Taskforce on Access to Climate Finance[11], given that finance and investment policy are symbiotically connected: policies help mobilize finance, and the availability of finance helps motivate policy reforms.

Proposal 3b. Endorse the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative and encourage G20 firms to follow the Net Zero Investment Framework

In addition, G20 economies should endorse new approaches that are helping mobilize investors in support of climate goals, including the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative (PAII)[12] and the Net Zero Investment Framework[13], and encourage G20 firms to follow this framework.

The Paris Aligned Investment Initiative (PAII) was established in May 2019 by the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) at the request of asset owner members, it now involves over 110 investors representing $33 trillion in assets. As of March 2021, the initiative has grown into a global collaboration supported by regional investor networks in Asia, North America, Europe, and Australasia.

The Net Zero Investment Framework, published in March 2021, provides a common set of recommended actions, metrics and methodologies through which investors can maximise their contribution to achieving global net zero global emissions by 2050 or sooner.

Figure 5: Net Zero Investment Framework

Conclusion

This policy brief has argued there are very specific and clear actions that would be taken to help grow climate FDI, in other words FDI that helps to achieve climate action.

First, mandate an expert group to align on a common understanding of climate FDI. Second, consider adopting 15 specific, targeted policies and measures in support of climate FDI. And third, create a COP Task Force on Climate Investment Policy and endorse new frameworks that encourage investors to increase climate FDI.

The G20 is the right forum to support scaling climate FDI in these three ways for three reasons.

First, climate is one area where G20 economies agree more action is needed, and especially coordinated action given that climate degradation is a public bad; the recent US-China joint statements and declarations on climate show that this is one area where cooperation is possible even between strategic rivals (State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2021; US Department of State, 2021a and 2021b).

Second, firms carrying out the bulk of FDI are from G20 economies, so helping them grow climate FDI will have a big impact on the world’s climate outcomes.

Third, once G20 economies adopt policies and measures in support of climate FDI, this will be both a signalling and demonstration effect for non-G20 economies to consider similar approaches.

Ultimately this agenda is in the interest of both the G20 and the rest of the world. There is consensus on achieving climate action.

We now need to align investment policy and practice behind this goal.

References

Brende, Børge, “The planet is in peril and business is ready to do its part”, 4 November 2021, World Economic Forum, Road to COP26, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/first-movers-coalition-the-planet-is-in-peril-and-business-is-ready-to-do-its-part/

Amendolagine, Vito, Rasmus Lema, and Roberta Rabellotti. “Green foreign direct investments and the deepening of capabilities for sustainable innovation in multinationals: Insights from renewable energy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 310 (2021): 127381, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652621016000

Dunning, John H. “Explaining the international direct investment position of countries: towards a dynamic or developmental approach.” In International Capital Movements, pp. 84-121. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1982, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-05989-8_4

Golub, S. S., C. Kauffmann and P. Yeres, “Defining and Measuring Green FDI: An Exploratory Review of Existing Work and Evidence”, OECD Working Papers on International Investment, 2011/02, OECD Publishing. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg58j1cvcvk-en

Johnson, Lise, “Green foreign direct investment in developing countries”, United Nations Environment Programme and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, October 2017, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/22280/Green_Invest_Dev_Countries.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit Policies for improving the sustainable development impacts of investment”, Consultation paper for 6th FDI Qualities Policy Network Meeting, 16 November 2021 https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/FDI-Qualities-Policy-Toolkit-Consultation-Paper-2021.pdf

OECD, “Policy Framework for Investment”, 2015, https://www.oecdilibrary.org/content/book/9789264208667-en

Sauvant, Karl P., Matthew Stephenson and Yardenne Kagan, “Green FDI: Encouraging Carbon-Neutral Investment”, Columbia FDI Perspectives, No. 316, 18 October 2021, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3943705

State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China, US issue joint declaration on enhancing climate action”, 11 November 2021, Xinhua, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/internationalexchanges/202111/11/content_WS618d0fe6c6d0df57f98e4d1b.html

Stephenson, Matthew, Iza Lejarraga, Kira Matus, Yacob Mulugetta, Masaru Yarime, and James Zhan, “SusTech Solutions: Enabling New Technologies to Drive Sustainable Development”, T20 Policy Brief, September 2021 https://www.t20italy.org/2021/09/09/sustech-solutions-enabling-new-technologies-to-drive-sustainable-development/

Stephenson, Matthew and Jose Vieira Martins, “Contribution to the OECD Public Consultation on Investment Treaties and Climate Change”, Investment Treaties and Climate Change OECD Public Consultation | January – March 2022, Compilation of Submission, 13 April 2022, pp. 210-213, https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/OECD-investment-treaties-climate-change-consultation-responses.pdf

United Nations, “Glasgow Climate Pact 2021”, Article 47, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2021_L16_adv.pdf

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “World Investment Report 2022: International Tax Reforms and Sustainable Investment”, 2022, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2022_en.pdf

UNCTAD, “Promoting Green FDI: Practices and Lessons from the Field”, IPA Observer No 5, 9 May 2016, https://unctad.org/fr/node/1330

UNCTAD, “World Investment Report 2010: Investing in a low-carbon economy”, 2010, https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2010

UNCTAD, “Creating an Institutional Environment Conducive to Increased Foreign Investment and Sustainable Development – Note by the UNCTAD Secretariat”, 2008, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/620228?ln=en

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis”, Media Note, 17 April 2021, 2021a, https://www.state.gov/u-s-china-joint-statement-addressing-the-climate-crisis/

US Department of State, “U.S.-China Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s”, Media Note, 10 November 2021, 2021b https://www.state.gov/u-s-china-joint-glasgow-declaration-on-enhancing-climate-action-in-the-2020s/

Whiting, Kate, “COP26: What is the First Movers Coalition?”, World Economic Forum, Road to COP26, 4 November 2021, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/first-movers-coalition-john-kerry-net-zero-decarbonization-green-tech/

World Bank Group (WBG), “Catalysing Investment for Green Growth: The Role of Business Environment and Investment Climate Policy in Environmentally Sustainable Private Sector Development”, November 2020, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/35056/Catalyzing-Investment-for-Green-Growth-The-Role-of-Business-Environment-and-Investment-Climate-Policy-in-Environmentally-Sustainable-Private-Sector-Development.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Appendix

Table 1: Proposals for Amending the DSU

| Initiator | Format | Proposed ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | WTO Communication JOB/GC/201 24 September, 2018 | In safeguarding and strengthening the DSM, Canada suggests that the WTO should:

|

| European Union (EU) +Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Switzerland | Ottawa Ministerial Conference 25 October, 2018 | These countries acknowledge that the blocking of the appointment of the AB members is instigated by the concerns raised regarding the functioning of the DSM. Accordingly, discussions to advance ideas to safeguard and strengthen the DSM need to be conducted. Moreover, they acknowledge the need to reinvigorate the WTO’s negotiating function. |

| EU, China, Canada, India, Norway, New Zealand, Switzerland, Australia, Republic of Korea, Iceland, Singapore and Mexico | WTO Communication WT/GC/W/752 26 November, 2018 | These countries acknowledge that concerns have been raised about the functioning of the DSM. They propose to amend certain provisions of the Understanding on Rules and procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (“DSU”):

|

| EU, China and India | WTO Communication WT/GC/W/753 26 November, 2018 | Regarding concerns which have been raised about the functioning of the dispute settlement system, these countries proposed the following ideas:

|

Footnote

1: This is a term first coined by The Economist (2019), referring to a pattern showing the slowing advancement of globalization following the end of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

2: The G20 has been reiterating its political support for WTO reforms over the years. The Saudi Arabia Presidency saw the launch of the Riyadh Initiative “on the Future of the WTO, which aims to identify common ground and shared principles for the next 25 years of the WTO” (WTO, 2021b). The G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration (G20, 2021) also emphasizes G20’s continued efforts to play an essential role in providing political support for WTO reform discussions. Indonesia’s Presidency of the G20, therefore, offers a crucial opportunity to take forward this legacy issue and discuss reform measures more concretely to take them to their logical conclusion.

3: Several points in the G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Meeting communiqué of 2020 refer to the G20’s acknowledgement of the need for the WTO reforms and its commitment to facilitate the same (G20, 2020).

4: The Riyadh Initiative on the Future of the WTO in the G20 Saudi Arabia and its reaffirmation in the G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration.

5: We recommend a multidimensional approach so that the concerns of member countries that fall under various levels of development are taken into consideration.

6: Making the MTS more effective through WTO reforms is important to address the challenges of ensuring broad-based recovery from the ongoing crises. While the WTO reform agenda is expected to figure prominently in this year’s G20 meetings, the members of the grouping need to show greater willingness by mobilizing the needed political will to set the direction and scope of the reform process.

- * The authors would like to thank Joachim Monkelbaan, Lead, Climate Trade, World Economic Forum and Jose Vieira Martins, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva (currently on leave from the Brazilian Ministry of the Economy), for research assistance. ↑

- After remaining stagnant in 2019 and 2020, climate FDI in renewables almost doubled in 2021, due to a 42 percent increase in investments in solar and wind energy generation, and a boom in green hydrogen energy. See UNCTAD (2022), p. 36. ↑

- Private climate FDI gravitates to mitigation as adaption investments are often public goods, characterized by steep upfront costs, long investment timelines, lack of a clearly identifiable revenue stream or unattractive risk-return profiles, which means they necessarily rely on public investment (UNCTAD, 2022). ↑

- The aim could, for instance, be to propose a definition for endorsement by the G20 in 2023. It would be important to ensure the expert group considers the perspectives of both developed and developing countries. ↑

- The 2022 World Investment Report states that “Climate change investments are broadly defined as mitigation investments in cleaner and/or more energy-efficient technologies supporting the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and adaptation investments, which are those in critical infrastructure, technologies and activities to improve resilience and help adapt to the consequences of climate change”. See UNCTAD (2022), p. 33. ↑

- Nearly all climate FDI adaptation projects are in water management (UNCTAD, 2022), though the focus of water management will be different in different economies. ↑

- The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Abhishek Saurav, Senior Economist, World Bank Group for this tripartite conceptual approach. ↑

- By ‘carbon negative’ we mean the investment produces a net downturn in the level of carbon in the economy. Another way to capture this idea is ‘climate positive’ but we find the former terminology a little more specific. ↑

- See Council for the Development of Cambodia, “The Suppliers Database with Sustainability Dimensions (SD2)”, https://sd2.cdc.gov.kh/. ↑

- See Sauvant, et al. (2021), with slight adaptation to focus specifically on climate action. ↑

- UK COP 26, “Finance”, https://ukcop26.org/cop26-goals/finance/ ↑

- Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, “Paris Aligned Investment Initiative”, May 2019, https://www.iigcc.org/our-work/paris-aligned-investment-initiative/ ↑

- Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, “Net Zero Investment Framework Implementation Guide”, March 2021, https://www.parisalignedinvestment.org/media/2021/03/PAII-Net-Zero-Investment-Framework_Implementation-Guide.pdf ↑