We offer theoretical foundations for the notion of social cohesion, provide empirical evidence for its drivers and impact on policy-relevant targets (such as GDP and well-being) and analyze its trend. We then offer several recommendations on how to foster social cohesion, pertaining to either its “objective” component – e.g. facilitating participation in association and community work, inserting “service-learning” into school curricula, acting for inclusive growth – and its “subjective” component – e.g. encouraging media and civil society to self-regulate to reduce the diffusion of false information, improving tolerance across groups and removing stereotypes over immigrants’ perceived lack of integration in society.

Challenge

Social cohesion is a crucial variable for economic governance. Social cohesion comprises both an “objective” component – i.e. the tendency by individuals to connect with others and participate in political and civic activities – and a subjective component – i.e. the perceptions that others can be trusted and relied upon in case of need. “Others” encompass both other citizens and the government. The beneficial effects of social cohesion are twofold. Social cohesion has a direct positive effect on the quality of institutions, and thus on economic growth. Moreover, feeling included in the society and knowing that one will not be left behind in case of need has a positive effect on individual well-being, both subjective and objective.

There is growing perception that social cohesion is decreasing, particularly in Western developed countries. Social cohesion is thwarted by social divisions triggered by income, ethnicity, political parties, caste, language, gender differences or other demographic variables. Rising levels of inequality and increased immigration undermine social cohesion, if these processes are not properly handled. Existing indicators of social cohesion show relative stability in aggregate, which is reassuring. Nonetheless, some worrying trends emerge analyzing its underlying components, particularly for what concerns acceptance of diversity and trust in governments.

Fostering social cohesion requires dealing with both its objective and subjective components. It involves correcting individual stereotypes over other groups in society, particularly immigrants and racially diverse others, improving tolerance between social and racial groups. These are goals difficult to achieve, because stereotypes and discrimination are rooted into individuals’ basic psychological attitudes, which lead people to categorize and draw distinctions across groups. Fostering social cohesion also calls for removing the spread of factually wrong information by the media, which often feed into divisive stereotypes. This is also a difficult task, because of the possibility of endangering freedom of expression and because individual judgement is often affected by values and stereotypical beliefs. Improving social cohesion also requires facilitating participation in associations and the undertaking of community work and the implementation of policies for inclusive growth. These challenges require a comprehensive and integrated approach. In many cases civil society and bottom-up initiatives should take center stage, while governments take on a subsidiary facilitating role only.

Proposal

1. Notion, drivers and trends

1.1 Conceptualizing social cohesion

Originating from the Latin word ‘cohaerere’ (to stick, to be tied together), social cohesion refers to the sense of community and the solidarity exhibited by people of a society. Building on seminal work by Tönnies (1887) and Durkheim (1897), a cohesive society can be defined as being “characterized by resilient social relations, a positive emotional connectedness between its members and the community and a pronounced focus on the common good” (Bertelsmann Foundation, 2013: 12). The literature identifies two different dimensions of social cohesion:

- Horizontal vertical: The horizontal dimension looks at inter-individual relationships – such as how much trust people put in others, or the willingness to join associations. The vertical dimension focuses on relationship between the individual and a superordinate institution, such as state and government, looking for instance at how much trust citizens put in their governments.

- Subjective (or cognitive) Vs. objective (or behavioral): Social cohesion encompasses both the perceived sense of belonging of a member to her group (subjective dimension), as well as the concrete manifestations of her attachment to (or embeddedness into) the group (behavioural dimension) (Bollen and Hoyle 1990). The perceived intimacy of a relationship is as important for an individual as the “objective” number of relationships that a person holds (Williams and Solano 1983).

The literature also discusses whether some shared values across community members and groups are necessary to define a society as cohesive. Although it is undeniable that all people should at least recognize the rule of law, and recognize the equal dignity of other citizens (see International Panel on Social Progress (IPSP) (2018): Chapter 2), for a society to be said to be fully established and functioning, we believe that it would be problematic to incorporate the component of shared values in the definition of social cohesion. It would be controversial both to identify which set of values is foundational for the society, and to appraise the extent to which such values are shared. We emphasize instead that tolerance and respect toward the values held by different social, racial and ethnic groups is an important constituent of social cohesion. In abstract, one may also do away with the requirement of tolerance (Chan et al., 2005). One could think that a society in which two groups live segregated from each other and one dominant group imposes on the other the respect of its own values is to some extent “cohesive” – in the sense of being cohesive within each sub-group. However, we embrace the view that this type of society should be morally reprimanded in the 21st century, and therefore we also put tolerance as a necessary component of social cohesion (Bertelsmann Foundation, 2013).

Drawing on Bertelsmann (2013) and Chan et al. (2005), the various components of social cohesion are enumerated in Table 1.

Table 1: Measuring Social Cohesion: A two-by-two framework (based on Chan et al. 2005 and Bertelsmann Foundation, 2013)

| Subjective component | Objective component | |

| Horizontal dimension | General trust in other citizens

Willingness to cooperate and help other citizens

Sense of belonging to the community and identification

Acceptance of diversity | Memberships in associations, trade unions, clubs etc.

Community work, donations

Respect for social rules

|

| Vertical dimension | Trust in institutions

Trust in leaders and public figures

Perception of fairness | Civic and Political participation

|

1.2 Drivers and ramifications of social cohesion

We here summarize the empirical work on the determinants of social cohesion and on its effects on other key variables for policy.

- Racial diversity: The existence of cleavages across ethnic and racial lines is often considered as the main obstacle to social cohesion (Easterly et al. 2006). Such cleavages are based on what the social psychology literature – particularly Social Identity Theory (see Appendix: Box 1) – identifies as a key component of human psychology, i.e. the tendency to categorize people into groups, to identify with one group and to draw comparisons across groups. Racial diversity offers a very strong group demarcation. At the cognitive level, identification of race occurs even faster than identification of gender or age in human brains (Eisenberg et al., 1998).

The seminal work of Alesina and La Ferrara (2002) supports the idea that more diverse communities are associated with lower levels of horizontal (but not vertical) trust, and in willingness to join associations, across US municipalities. Hence, racial diversity can be thought of as lowering social cohesion. They account for this evidence with aversion to diversity. Some subsequent studies replicated this result (Putnam 2007) in the United Kingdom or Canada, while others did not (Nannestad 2008). Interestingly, no correlation between generalized trust and ethnic fractionalization was found at the national level across 20 European countries (Hooghe et al. 2009). Hence, the effect of ethnic diversity may be specific to culture or historical trajectories.

- Economic inequality: Kawachi et al. (1997) demonstrate a generally negative impact of income inequality on horizontal trust. This result may be due to lack of optimism that one will benefit from societal progress (Uslaner 2002). Interestingly, evidence has been provided that immigration has a negative effect on social cohesion only in countries with high levels of economic inequality (Kesler and Bloemraad 2010).

- Education: A positive relationship between education and social cohesion has been empirically confirmed (Helliwell and Putnam 2007). The reason is that creating a mutual identity and facilitating cooperation within the society is one of the main purposes of public education (Heynemann, 2000).

- Historical events: In line with the idea that cultural values may be very persistent over time (Bisin & Verdier 2015), there is also evidence that historical events influence social cohesion in the long term. Nowadays trust is still lower among ethnic groups in Africa which were most affected by slave trade in the past (Nunn & Wantchekon 2011). Likewise, Northern Italian cities with more inclusive political structures in the medieval still possessed higher levels of social capital nearly a thousand years later (Putnam et al. 1993).

Social cohesion has important ramifications on variables that are of clear interest for individuals’ well-being:

- GDP: Social cohesion has been demonstrated to have both a direct positive effect on GDP (Foa 2011), partly caused by the huge economic costs of inter-racial conflict and war, or an indirect effect, through the facilitation of better institutions like the juridical system or freedom of expression (Easterly et al. 2006). Similarly, it has been shown that countries whose GDP was more strongly affected by the economic crises in the 1970s had scarcely cohesive societies (Rodrik 1999).

- Subjective well-being: It has been shown that increased trust has the same impact on life satisfaction as an increase by two-thirds of household income (Helliwell and Wang 2011). A positive relationship between well-being and overall social cohesion has also been established (Delhey, J., & Dragolov, 2016).

- Health: Data from 39 US states indicate that social cohesion fosters mental (Kawachi and Berkman 2001) as well as physical health, even moderating the effect of income equality on increased mortality. It has also been demonstrated that a disinvestment in social capital leads to the rise of mortality rates (Kawachi et al. 1997).

1.3 Evolution of social cohesion

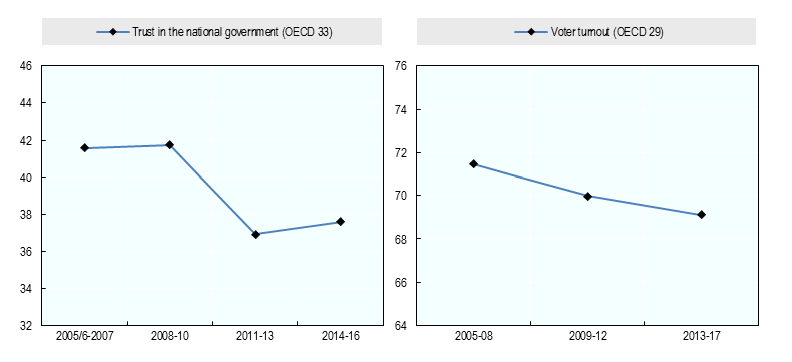

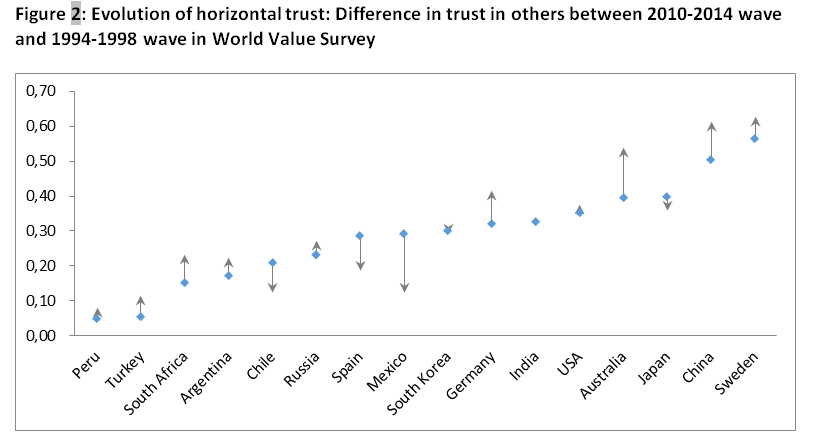

The Social Cohesion Radar of the Bertelsmann Foundation (2013) has measured social cohesion in four waves across 34 OECD countries. The analysis shows broad international differences, with Scandinavian countries being ranked at the top throughout all four waves, Eastern European countries at the bottom, and Central European countries in the middle. Whereas the levels of social cohesion in Canada and US were similar to those in Northern Europe in the 1990s, both countries experienced substantial declines during the last 15 years. Conversely, social cohesion has remained stable – but at low levels – in several Southern European Countries that were severely affected by the Great Depression originated in 2008. This may be due to the stability over time of the objective dimension, particularly association membership. On the contrary, the subjective component experienced a decrease in trust in institutions in many countries (see Figure 1 in the Appendix), and even more markedly, in acceptance of diversity. Germany is a notable case, with acceptance of diversity dropping while the overall indicator of social cohesion has risen. The evolution of World Value Survey indicators of horizontal trust does not show any obvious trend over a time span of about 20 years (see Figure 2). It would show very little variation comparing the wave before and after the 2008 Great Depression (not reported).

It is often claimed that social cohesion is decreasing in our societies because of rising inequalities and the impact of the Great Depression. Although it is difficult to draw generalizations, the analysis of these indicators would tentatively suggest that Western societies are overall more resilient and cohesive than one could think of. This is of course a consequence of the fact that all the different components of the index enter with equal weight in the overall index. In that sense, it is worrying to see a drop in acceptance of diversity and trust in institutions, while it is reassuring that trust in others does not seem to follow the same trend. We also point out that indicators of how much people can expect to be supported and helped by others, especially in a time of crisis, are absent from international social survey. Since this seems to be an important constituent of sense of community and of the perception of solidarity that citizens experience, it seems that a fundamental component of social cohesion cannot be properly measured.

Figure 1: Evolution of trust in national government and voter turnout

Note: For trust in the national government, the OECD average is population-weighted and excludes Iceland and Luxembourg, due to an incomplete time series. For voter turnout, the OECD average has been calculated across four-year periods. This required excluding Austria, Finland, Italy, Luxembourg and Mexico. Chile is also excluded since compulsory voting was dropped in 2012, introducing a break in the series.

Sources: For trust in the national government: OECD calculations based on Gallup World Poll, www.gallup.com/services/170945/world-poll.aspx. For voter turnout: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) (2017), www.idea.int, the register of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal for Costa Rica, and the Federal Statistical Office (FSO) of Switzerland.

2. Recommendations

2. Recommendations

Since social cohesion is based on both an objective and a subjective component, we think it is important that policy-makers engage with both aspects.

2.1 Tackling the “objective” side of social cohesion

The objective aspect of social cohesion refers to individuals’ propensity to interact with others, in particular in joining associations, participating in community work and engaging in political activities such as voting.

Key recommendation 1: Facilitate the constitution and the participation in associations and community work

Although the actual efficacy of participating in association on trust had been put in doubt in macro-level analysis (Knack and Keefer, 1997), micro-level evidence seems concordant in stressing the positive influence of participation in association on social cohesion. In particular, Hurtado & Carter (1997) shows the positive relationship between association involvement and nurturing the sense of belonging to a community, a component of the “horizontal” dimension of social cohesion. Experimental evidence shows that participants in associations show higher pro-social motivations than others, another “horizontal” component of social cohesion (Anderson et al., 2004; Degli Antoni and Grimalda, 2016). Since micro-level evidence permits better than identification than macro-level one, we conclude that participation in association is an important mechanism to foster social cohesion We therefore recommend that governments facilitate both the creation of associations and the likelihood with which people can join. This may take the form of providing fiscal incentives for the constitution of associations, in particular through tax discounts for donations to charities, conceding loans for start-up projects to associations whose goals seem particularly worth of support, providing the general public with information over associations’ activities. By its very nature, individuals’ genuine and autonomous propensity to engage in such activities is needed in order to provide a “social dividend”. Forcing individuals to take part in such activities would most likely lead to no result or even negative results, because making participation in community work compulsory may actually stir anti-social or sabotaging behavior.

Key recommendation 2: Offer educational programs providing students with the opportunity to engage in community work and association membership.

So called service-learning, i.e. the practice of inserting active participation in volunteer associations as a requirement of school curricula, has been implemented in some countries such as the US, though never at an extensive scale. Analyses of its impact are unambiguously positive. Not only does service-learning enhance the probability of future volunteerism (Griffith 2010), but also personal well-being and life satisfaction in the long run (Bowman et al. 2010). It also reduces teenage pregnancy, alcohol consumption and criminal conduct (Allen et al. 1997), while improving educational achievements, political activity and attitudes toward civic participation (Hart et al. 2008). The available evidence clearly indicates that the establishment of such programs would have beneficial effects for both social cohesion and well-being.

Key recommendation 3: Citizen involvement in the implementation of public goods

Another constituent element of social cohesion is rule abidance. Incentivizing social norms compliance “from above” may run the risk of backfiring through so-called crowding-out effects (see Appendix: Box 2). This is the tendency for “intrinsically motivated” people to give up on pro-social behavior when material incentives are set to favor such pro-social behavior. There have been nonetheless a number of initiatives in which public authorities offered support and coordination, rather than monetary incentives, in order to provide public goods. One example is the so-called “Neighbourhood Watch” initiative, whereby citizens of a certain neighborhood are encouraged to take explicit actions to watch over their district of residence, and to exchange information over security issues with other participants in the scheme and, most importantly, with the police. The general assessment of these initiatives is that they are capable of reducing crime activities (Bennett et al., 2006) and increase citizens’ sense of security (Henig, 1984). Furthermore, they provide a valuable exercise in direct democracy by involving citizens not only in the adoption, but in the implementation of public policies. We believe that public authorities may have a beneficial impact on social cohesion by encouraging such activities, without or with very limited use of monetary incentives, and offering coordination among citizens as well as information pooling. A number of public goods could be provided in this way, in activities as broad as improving the respect of traffic laws, cleaning up litter in the park, improving collection and recycling of waste.

Key recommendation 4: Facilitate the opportunities for citizens’ political engagement and improve the institutional reception to bottom-up initiatives

Our underlying assumption is that individuals derive a positive sense of inclusion from actually taking part in democratic activities, particularly voting. Monetary incentives for voters to turn out on elections days will again trigger crowding-out effects. We believe that reducing the costs to access the voting booths are better devices to encourage participation. Increasing the number of polling stations, extending their opening time, fixing voting on festive days rather than during the working week, would have the desired effect of encouraging people to take part.

Political participation is not limited to voting. Supporting a petition, quizzing one’s political representative, taking part in a public debate, at whatever level, are all activities that can increase the sense of inclusion in society. The political psychological literature tells us that having a “voice” – namely, having the opportunity to express one’s opinion over a certain matter – is very important for individuals, often well beyond the instrumental value that this voice might have on final outcomes (Grimalda et al., 2016). Social media have already made possible to express one’s political opinions, as online petitions can mobilize millions of individuals – as we have recently witnessed in the “#Metoo” campaign. We support the spread of these initiatives and we urge governments to respect and pay attention to these campaigns. We advise governments and politicians to establish regular hearings of citizens and to take action to implement the demands emerging from these campaigns.

Key recommendation 5: Comply with a strategy of inclusive growth

In other works of this taskforce we have laid out the foundations of inclusive growth (Boarini et al, 2017). That is a process whereby growth (a) is meant to benefit all economic and social groups in the population, leaving no one behind; (b) considers a comprehensive notion of well-being that is not limited to income but looks at other aspects of objective and subjective well-being, such as in particular individuals’ inclusion in the society. Several variables that are conducive to inclusive growth are also determinants of social cohesion. In particular, reducing economic and social inequality and facilitating the access to education at all levels can improve both inclusive growth and social cohesion.

2.2 Tackling the “subjective” side of social cohesion

Dealing with individuals’ process of opinion formation is a very delicate matter, because the need to sanction the transmission of factually wrong information needs to be balanced with the need to respect individuals’ autonomy in forming their own values and views of the world. Nevertheless, we believe that there is ample space for action even on this front. In Box 3 we clarify in which sense and how an individual may end up having an incorrect vision of reality. We assume that individuals receive imperfect “signals” over the true state of affairs, and that value judgement might affect the interpretations of such signals because of cognitive dissonance. Even if cognitive or judgement errors are inevitable, it is obvious that the more a fact becomes uncontroversial, the higher the probability that the individual will eventually form the correct view on such fact. In the specific case of social cohesion, the more the government acts to foster social cohesion, the more likely it is that the individual will in the end form the correct opinion on how much she can expect from the rest of society. For this reason, we encourage policy-makers to take measures to improve the set of variables that has been identified as relevant determinants of social cohesion.

Key recommendation 6: Improve integration of immigrants in society

In many Western countries integration is subject to a “test” of knowledge of the language, culture and institution of the recipient countries. Although we believe that language is important, the effectiveness of such tests has been doubted. We propose alternatives.

One of the possible causes of discrimination is so called statistical discrimination. That is the phenomenon whereby individuals belonging to a certain group are attributed the same characteristics that are believed to hold for the whole group. For instance, if a belief is held that Italians are bad car drivers, then statistical discrimination will hold every Italian citizen as a bad driver. Note that the belief may be true. Most typically, though, the beliefs are unfounded and people belonging to certain groups will be stereotypically discriminated against.

It goes without saying that immigrants in many countries are statistically discriminated against on the basis of stereotypical beliefs that they lack work ethic, or hold too different values from those held by natives in order to be integrated in society. An effective way to break down such beliefs relies once more, we believe, on volunteerism and community work. We envisage immigrants’ participation into voluntary associations involving both natives and immigrants, which perform beneficial activities for the community.

Such type of activities would have many advantages in addition to the public goods they provide. They would permit “transmission” of the relevant social norms from natives to immigrants, let alone language skills. They would contribute to remove natives’ prejudices associated with immigrants’ poor work ethic, or their unwillingness to integrate into the native community. Moreover, they would demonstrate to the native population immigrants’ willingness to contribute to the common good. This proposal shares some similarities with Atkinson (2015)’s advocacy of the state acting as an employer of last resort in activities that have public utility. As such, the involvement in such activities should not be compulsory but accessible on a voluntary basis by both immigrants and associations. Public authorities should nonetheless play a role in encouraging immigrants’ participation explaining their benefits. Associations may receive subsidies to implement these activities, though preferably this should not be the case to remove crowding-out effects. The existence of such activities and their beneficial consequences should be disseminated across citizens.

Key recommendation 7: Improve reciprocal tolerance across different ethnic and social groups

Defining in detail strategies to improve tolerance clearly lies outside the scope of this policy brief. We can only indicate some basic principles. The social psychological literature is divided over so-called conflict and contact theory, which state that mixing racial groups causes either further radicalization (conflict theory), or, on the contrary, the removal of psychological cleavages (contact theory) (see Putnam, 2007, for a review). We do not believe that integration strategies can always be effective in the short-term, hence we are not surprised that conflict theory appears to be dominant in many instances. Nonetheless, we note that the existence of very diverse attitudes toward immigration across geographical regions in a country or across countries – e.g. negative attitudes towards immigrants are concentrated in Eastern Germany within Germany, or in Eastern and Southern Europe within Europe – point to the extreme power that different educational systems can have in shaping attitudes towards immigration. We share Putnam’s (2007) view that a society that is racially and ethnically diverse will enrich its citizens in the long term under many perspectives – not least the economic one. Hence, societies should be prepared to pay the short-term costs of removing segregation barriers in order to reap the long-term benefits of a diverse society.

2.2.2 Facilitating individuals’ formation of autonomous and factually correct opinions on society

Key recommendation 8: Engage in a public dialogue with the media, broadly defined, in order to discard the diffusion of so-called “fake news”

The rapid diffusion of social media has brought to the fore the possibility of so-called “fake news” – the artefactual diffusion of false facts, mainly to shift political or electoral consensus. Finding strategies to intervene on this issue is complicated because of the risk of limiting freedom of expression. In fact, observers have accused governments, such as recently the Indian one, that their intent to crack down on fake news hides the willingness to introduce de facto censorship on media. We believe that even in this case bottom-up solutions coming from civil society are to be preferable to direct bans or impositions emanating from governments. We believe that it is necessary to engage in a national and global dialogue among governments, civil society and the media sector – broadly defined. The government should encourage the media sector to voluntarily subscribe to codes of ethics and codes of conduct aiming to eradicate the phenomenon of false reporting or fake news. This strategy may also rely on auditing and certification by credible authorities independent from the government over the reliability of a certain news source – be it an official media company or a Twitter account. An example of this approach is laid out in the “Journalism Trust Initiative”.[1] Another similar approach would rely on empowering “fact-checking” associations, whose aim is to highlight and disseminate the misreporting of information.

Key recommendation 9: Identify sensitive areas for trust in governments and implement policies to improve consensus

Extensive survey research permits to identify areas of government activities to which public opinion is particularly sensitive. Recent research conducted within the OECD Trustlab project[2] identifies government integrity – meaning, mainly, refraining from bribery and corruption practices – as the characteristic that is of greatest importance to the public of four Western countries. This factor is nearly twice as important as other factors, such as effectiveness and responsiveness to citizens’ demands. This evidence clearly suggests that the one area where governments are expected to come clean to the public is that of perceived corruption.

Appendix

Existing policies

African Union Employment and Social Cohesion Fund

The AU is currently establishing a fund in order to defy unemployment and socioeconomic exclusion, in particular of women and young individuals.

https://au.int/sites/default/files/newsevents/workingdocuments/34086-wd-progress_report_on_the_establishment_of_the_au_employment_and_social_cohesion_fund_english.ppd

ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASSCC) Plan of Action

The ASSCC aspires to foster social cohesion at the communal level through the creation of training centers, a regional identity and a region-wide network of NGOs.

https://asean.org/?static_post=the-asean-socio-cultural-community-ascc-plan-of-action

Council of Europe European Social Cohesion Platform (PECS)

The PECS was established in 2016 with the aim of guaranteeing equal social rights and the respect of human dignity to all citizens of the EU and preventing discrimination of refugees.

https://www.coe.int/en/web/turin-european-social-charter/european-social-cohesion-platform-about

FAO Smart Territories Platform

Created in 2016, the Smart Territories Platform launches different initiatives to promote social cohesion in Latin America and the Caribbean, for instance by supporting family agriculture systems or preventing territorial conflicts.

https://www.fao.org/in-action/territorios-inteligentes/componentes/cohesion-social/metodologias-y-herramientas/es/

Government of Canada Promoting Social Cohesion in Iraq

This project, finished in 2017, provided educational activities for internally displaced Iraqis to improve their negotiation, mediation, project planning and implementation abilities.

https://w05.international.gc.ca/projectbrowser-banqueprojets/project-projet/details/D001622001?Lang=eng

Box 1: Social identity and inter-group psychologySocial Identity Theory (SIT) defines a group by a number of individuals perceiving to belong to the same social category. This-approach posits that individuals seek to obtain positive social identity, which in turn is mainly achieved through advantageous comparisons (positive distinctiveness) between the own group (the ingroup) and relevant outgroups. This process comprises three steps. Categorization involves the assignment of individuals to certain social categories. It is followed by identification through which a person affiliates himself to one or more of these groups. Finally, the comparison itself takes place. Which characteristics make a group a ‘relevant’ outgroup depends e.g. on the cultural context or on situation-specific cues [stimuli] (Tajfel and Turner 1986). A supporter of a football team may compare himself to the fan base of a rival while both clubs are playing against each other. However, the rivaling supporters in most cases will not constitute a relevant outgroup for him while he is at work. This example also illustrates that people usually belong to more than one ingroup. There is broad empirical evidence that at least categorization is a strong automatic process which is difficult to suppress. For instance, participants of an experimental videogame mistakenly shot unarmed African Americans significantly more often than unarmed Whites (Correll et al. 2002). Categorization and, consequently, discrimination based on ethnicity as well as on sex and religion have been shown to take place also in real settings like the labor market (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004, Adida et al. 2010), the rental housing market (Bosch et al. 2010) or different product markets (Riach and Rich 2002). The consequences of this approach are broadly discussed. During a long time, a high attachment to the ingroup was considered a major source of outgroup hostility. Indeed, discrimination may occur when economic inequality and thus competition for scarce resources are high or if intergroup comparisons are based on moral superiority. Furthermore, the depiction of a hostile outgroup can provide a mechanism through which political leaders intent to increase identification with the ingroup. While comparison is frequent, the results of several empirical studies question the assumption that ingroup attachment and outgroup aggression are intrinsically tied. This applies in particular to societies whose members hold multiple roles and therefore belong to various groups (Brewer 1999). However, achieving a complex social identity (also called transcendent identity), that is accepting differences between one´s ingroups, places high demands on the individual. Especially if ingroups share certain characteristics, if they comprise mainly the same members or if one group-membership is much more salient than the others, a transcendent social identity demands elaborated cognitive strategies. These strategies include the tolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty, openness or lowering the need for power. Thus, situations associated with high levels of cognitive load or stress promote lower complexity, whereas a heterogeneous social environment normally fosters self-transcendence. If achieved, a highly complex social identity is likely to increase tolerance towards outgroups in general without reducing ingroup attachment (Roccas and Brewer 2002). |

Box 2: The “crowding out” effectEvery time the government tries to incentivize through monetary means pro-social behavior among individuals, it runs counter to the so-called crowding-out effect. This can be defined as the phenomenon whereby the supply of an altruistic action – such as blood donations – decreases when individuals receive a monetary compensation for it. The first scholar to propose this effect was Richard Titmuss (1970), who claimed that indeed the overall amount of blood donations decreased when monetary compensation was introduced. The theoretical explanation of this phenomenon has to do with what Deci and Ryan (1987) called “intrinsic motivations”. These are motivations that by definition are not instrumental to obtain any reward. Extrinsic motivations are on the contrary oriented to reaping some kind of financial reward. Deci and Ryan (1987) claim that when financial motivations are introduced, then people who are motivated by intrinsic motivations will cease behaving pro-socially, because their behavior can no longer be construed as a purely altruistic act. Benabou and Tirole (2006) developed a theory, in which people aim to keep a certain self-image. If they “choose” an altruistic self-image, then only actions that may be fully construed as being altruistic can contribute to building that social image. Bowles and Polania-Reyes (2012) notices that crowding effect should be assessed through counterfactuals rather than in absolute terms. His point is that, even if we observe that the supply of donated blood does not decrease overall when monetary incentives are introduced, it is possible that at least some individuals decreased their supply. Hence, had crowding out been absent, the overall supply would have been higher. The general conclusion of the empirical evidence on the crowding-out effect is that this is not complete, but sizable. In particular, for every dollar that is spent to incentivize a certain pro-social action, half of it is “crowded out”. This means that incentivizing altruistic actions may be efficient, but not as efficient as one may expect. In a controlled natural experiment in Sweden, Mellström and Johannesson (2008) find crowding out effects to be significant for women but not for men. |

| Box 3: A cognitive model of opinion formation We rely on a model of individual’s opinion formation that is based on the idea that individuals receive “imperfect signals” over facts and the determinants of such facts. Signals are imperfect in the sense that (a) they may lead to ignoring fact F or believe that fact F is not true; (b) wrong inferences are made on the causes of fact F; For example, let us assume that an individual receives from a media channel the following two pieces of information regarding a fact F and its cause: (1) Fact F: “Criminality rates have increased in country X” (2) Cause C of Fact F: “Immigrants are largely responsible for F”. The individual commits a factual error if she believes that fact F is true whereas it is in fact wrong. The individual commits an interpretation error if she believes that the cause of F is C, whereas the true cause is another. We believe that it is important to distinguish between factual errors and interpretation errors, because factual errors are more easily to ascertain than interpretation errors. Causes of facts may be multiple and by their very nature difficult – or even impossible – to pinpoint. Hence, the possibility of errors is much higher with interpretation of facts rather than with facts. In the examples above, though, both F and C are observable and therefore ascertainable.

Signals are imperfect for three reasons: (a) Cognitive dissonance: as illustrated in Festinger’s (1962) seminal theory, individuals strive to avoid discordance between their beliefs, ideas and values on one side, and the facts they observe on the other side; Hence, if either a fact or the interpretation of the fact contrasts with their value and belief system, individuals may ignore this fact; (b) Media manipulation: Facts are either distorted or erroneously reported – as in the case of so-called “fake news”. The censoring by media of important facts is another instance of manipulation. (c) Random error: As in every process of information transmission, a margin of statistical error in the interpretation of facts is unavoidable. |

[1] https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/rsf-trust-initiative

[2] https://www.oecd.org/naec/TRUSTLAB_NAEC_final.pdf

References

- Adida, C. L., Laitin, D. D., & Valfort, M. A. (2010). Identifying barriers to Muslim integration in France. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (52), 22384-22390.

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of public economics, 85 (2), 207-234.

- Allen, J. P., Philliber, S., Herrling, S., & Kuperminc, G. P. (1997). Preventing teen pregnancy and academic failure: Experimental evaluation of a developmentally based approach. Child Development, 68 (4), 729-742.

- Anderson, L. R., Mellor, J. M., & Milyo, J. (2004). Social capital and contributions in a public-goods experiment. American Economic Review, 94(2), 373-376.

- Andreoni, James. (2004). ʺPhilanthropy. L.‐A. Gérard‐Varet, S.‐C. Kolm and J. Mercier Ythier, Handbooks of Giving, Reciprocity and Altruism. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland.

- Atkinson, A. B. (2015). Inequality. Harvard University Press.

- Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American economic review, 96(5), 1652-1678.

- Bennett, T., Holloway, K., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Does neighborhood watch reduce crime? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2(4), 437-458.

- Berger-Schmitt, R. (2002). Considering social cohesion in quality of life assessments: Concept and measurement. Social indicators research, 58 (1-3), 403-428.

- Bertelsmann Foundation (2013). Social Cohesion Radar. Measuring Common Ground. An International Comparison

- Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American economic review, 94 (4), 991-1013.

- Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2011). The economics of cultural transmission and socialization. In: Benhabib, J., Bisin, A., & Jackson M. O. (Eds.). Handbook of social economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Boarini R, Causa O, Fleurbaey M, Grimalda G, Woolard I (2017). Reducing inequalities and strengthening social cohesion through Inclusive Growth: a roadmap for action. G20 Insights. T20 Task Force on Global Inequality and Social Cohesion.

- Bosch, M., Carnero, M. A., & Farre, L. (2010). Information and discrimination in the rental housing market: Evidence from a field experiment. Regional science and urban Economics, 40 (1), 11-19.

- Bowles, S., & Polania-Reyes, S. (2012). Economic incentives and social preferences: substitutes or complements?. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 368-425.

- Bowman, N., Brandenberger, J., Lapsley, D., Hill, P., & Quaranto, J. (2010). Serving in College, Flourishing in Adulthood: Does Community Engagement During the College Years Predict Adult Well‐Being? Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 2 (1), 14-34.

- Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of social issues, 55 (3), 429-444.

- Carron, A. V., & Spink, K. S. (1995). The group size-cohesion relationship in minimal groups. Small group research, 26 (1), 86-105.

- Chan, J., To, H. P., & Chan, E. (2006). Reconsidering social cohesion: Developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Social indicators research, 75 (2), 273-302.

- Correll, J., Park, B., Judd, C. M., & Wittenbrink, B. (2002). The police officer’s dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83 (6), 1314.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 53 (6), 1024.

- Degli Antoni, G., & Grimalda, G. (2016). Groups and trust: Experimental evidence on the Olson and Putnam hypotheses. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 61, 38-54.

- Delhey, J., & Dragolov, G. (2016). Happier together. Social cohesion and subjective well‐being in Europe. International Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 163-176.

- Durkheim, E. (1897). Le suicide: Etude de sociologie. Paris: Felix Alcan.

- Easterly, W., Ritzen, J., & Woolcock, M. (2006). Social cohesion, institutions, and growth. Economics & Politics, 18 (2), 103-120.

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (1998). Prosocial development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

- Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.

- Foa, R. (2011). The Economic Rationale for Social Cohesion–The Cross-Country Evidence. OECD International Conference on Social Cohesion and Development citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.230.2442&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Griffith, J. (2010). Community Service Among a Panel of Beginning College Students: Its Prevalence and Relationship to Having Been Required and to Supporting “Capital”. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39 (5), 884-900.

- Grimalda G, Kar A, Proto E (2016). Procedural Fairness in Lotteries Assigning Initial Roles in a Dynamic Setting, Experimental Economics, 19: 819-841. doi: 10.1007/s10683-015-9469-5.

- Hart, D., Matsuba, M. K., & Atkins, R. (2008). The moral and civic effects of learning to serve. In: Nucci, L. P., & Narvaez, D. (Eds.). Handbook of moral and character education. New York: Routledge

- Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2007). Education and social capital. Eastern Economic Journal, 33 (1), 1-19.

- Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2011). Trust and wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1 (1), 42-78.

- Henig, J. R. (1984). Citizens against crime: An assessment of the neighborhood watch program in Washington, DC. Occasional Paper, 2.

- Heyneman, S. P. (2000). From the party/state to multiethnic democracy: Education and social cohesion in Europe and Central Asia. Educational evaluation and policy analysis, 22 (2), 173-191.

- Hooghe, M., Reeskens, T., Stolle, D., & Trappers, A. (2009). Ethnic diversity and generalized trust in Europe: A cross-national multilevel study. Comparative political studies, 42 (2), 198-223.

- Hurtado, S., & Carter, D. F. (1997). Effects of College Transition and Perceptions of the Campus Racial Climate on Latino Students´ Sense of Belonging. Sociology of Education, 70 (4), 324-345.

- International Panel on Social Progress (IPSP) (2018). “Rethinking Society for the Twenty-First Century: Report of the International Panel on Social Progress”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

- Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban health, 78 (3), 458-467.

- Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K., & Prothrow-Stith, D. (1997). Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American journal of public health, 87 (9), 1491-1498.

- Kesler, C., & Bloemraad, I. (2010). Does immigration erode social capital? The conditional effects of immigration-generated diversity on trust, membership, and participation across 19 countries, 1981–2000. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 43 (2), 319-347.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly journal of economics, 112(4), 1251-1288.

- Mellström, Carl, and Magnus Johannesson. “Crowding out in blood donation: was Titmuss right?.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6.4 (2008): 845-863.

- Nannestad, P. (2008). What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 413-436.

- Nunn, N., & Wantchekon, L. (2011). The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. American Economic Review, 101 (7), 3221-52.

- of Social Cohesion. Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann-Foundation.

- Pahl, R. E. (1991). The search for social cohesion: from Durkheim to the European Commission. European Journal of Sociology, 32 (2), 345-360.

- Putnam, R. D. (2007). E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty‐first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian political studies, 30(2), 137-174.

- Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic institutions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Riach, P. A., & Rich, J. (2002). Field experiments of discrimination in the market place. The economic journal, 112 (483), 480-518.

- Roccas, S., & Brewer, M. B. (2002). Social identity complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6 (2), 88-106.

- Rodrik, D. (1999). Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict, and growth collapses. Journal of economic growth, 4 (4), 385-412.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel, S., & Austin, W. G. (Eds.). Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Titmuss, Richard M. (1970). The Gift Relationship. Allen and Unwin.

- Tönnies, F. (1887). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Abhandlung des Communismus und des Socialismus als empirischer Culturformen. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press