Education in developing countries faces the daunting responsibility of trying to enact realistic policies and strategies, while keeping to the principles and targets of SDG4 and the demands of Results-Based Financing. The education agenda demands ambitious and transformative changes that require significantly more financial resources and many related efforts to achieve learning outcomes. However, there is insufficient knowledge on how to achieve these goals, and we have yet to come up with more effective modalities and mechanisms for aid. This brief presents pitfalls that await these countries and partners and proposes possible policy actions and corresponding measures.

Challenge

Education is expected to play fundamental roles in realizing sustainable development under the transformative and ambitious Agenda 2030. In developing countries, thanks to massive efforts put into universalizing basic education, we have seen encouraging progress in expanding the education system, resulting in higher enrollment rates and better equity in access to education.

Undeniably, more financial resources are needed to meet the challenges called for by SDG4. What is critical now is to transform the manner in which education financing mechanisms work, while being careful to avoid the following pitfalls. Otherwise, additional resources, even if mobilized domestically and externally, will not achieve SDG4 and other SDGs.

Pitfall 1. Political and popular attention has shifted from access to the quality of education, above all learning outcomes, which include knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, as well as employability; while at the same time ensuring equity and inclusiveness. Policies are tasked with addressing them all at once by running multiple tracks of major reform in parallel. This makes it difficult for individual reform measures to take root and institutionalized, endangering the sustainability of their effects.

Pitfall 2. Present discussions on education financing are largely preoccupied with expanding the resource base and increasing resources flowing into education, mobilized by “innovative financing” measures such as taxes, dues, other obligatory charges, impact bonds, debt swaps, and crowdfunding.[1] However there is little evidence to show that more resources lead to inclusive and improved “learning.”

Pitfall 3. In response, the international aid community has made increasing use of the “Results-Based Financing (RBF)” mechanism, under which resources are provided on verification of achievement of pre-determined results.[2] Results are measured by indicators so-called “Disbursement-Linked Indicators (DLIs).” However, in most cases these “results” are intermediate ones, and countries are left with the responsibility of moving from intermediate to final results. Furthermore, stakeholders in developing countries lack crucial knowledge on how to reach these final results.

Pitfall 4. The process associated with RBF includes education planning, analysis of policy issues, factor identification (setting reform agenda and investment priorities), policy appraisal and learning assessment. This process is often driven by the requirements of external development partners, and thus is likely to depend on methods that are developed and brought in by them to aid recipient countries. Though useful, this approach risks the process being unduly influenced by external partners and their expertise, which tends to limit participation of local stakeholders and use of their knowledge. This undermines ownership of the knowledge of local stakeholders.

[1] Burnett and Birmingham (2010) and UNESCO Bangkok (2015)

[2] World Bank (2017)

Proposal

Policy Action 1a. Ensure realistic and feasible policy planning

The focus on learning outcomes is quite justified. When more children complete primary education with unsatisfactory learning, pressure on different levels of education is intensified. Children need to be prepared for school through expanded pre-primary education. Children in primary education must finish more efficiently. Children need to be equipped with the knowledge and skills required for life, before leaving secondary education, which is the end of schooling for the vast majority of youth in developing countries.

Policy issues to make these goals a reality require that remaining issues be tackled: (reaching unserved groups in the population, providing essential school inputs, employing more teachers, for instance) as well as new issues (reorienting the curriculum, improving teaching and learning conditions with innovative means, for instance). Equity and inclusion are not merely issues of access but more pressingly of learning. Obviously, more financial resources need to be mobilized. Adding to the demands, the international community reinforces expectations of the education sector by advocating for the SDGs/SDG4, which link education with other related sectors.

This intensifies the pressure on governments for education to satisfy multiple expectations simultaneously and to crowd the reform agenda with new initiatives. These expectations are transmitted through reform measures, which extend down to the venues where teaching and learning take place, further burdening the implementation capacity of the existing system and its key players. Moreover, the timeframe envisaged for implementation is often too short.

G20 is in a crucial position to advocate and collaborate in country to ensure that the education policy framework accompanying this broad reform agenda is realistic and feasible, particularly from the viewpoint of actors who implement policy. Critical implementation issues include the overall volume of work, timeframe, sequencing, and budget.

A proposed strategy and means for implementation are presented in a subsequent section, as they are related to several policy actions (see Figure 1 below).

Policy Action 1b. Build ownership, and institutionalize new ways to ensure sustainability

Successful implementation of such a complicated education reform agenda requires that it be based on and nurturing a sense of ownership among stakeholders, essentially those who implement it at the field-level. Reforms which add new tasks, involves different ways of thinking and actions, have to build on shared views and vision for change from the very beginning of the reform process. This requires bi-directional communication between the central policy makers and the rest of the system.

In addition, the education reform needs to maintain positive and consistent results for the benefits to be realized. For the sustainability of the reform results, each step of the reform process has to be internalized and institutionalized[1]. It is desirable that issues are identified and solutions come from within, to maintain motivation and ownership of the process. Where ideas of the reform and its measures are introduced from the top, or by the pressures from external sources, as is often the case with education in developing countries, we have to be even more sensitive to make sure the reform process is not derailed.

These essentials are well-known for successful reform, but are too frequently overlooked, as education reform works to tackle complicated issues comprehensively.

G20 leaders should collaborate with other partners in mainstreaming measures to respect the ownership and institutionalization of such critical steps in the education reform process.

Policy Action 2a. Use reform measures that fit their purposes

The experts that have estimated the costs of achieving SDG4[2] call for an exponentially more investment in education. The debate goes beyond increasing domestic financing (expanding the tax base) or official development assistance, and proposes establishment of a new financial mechanism for education (such as the International Financing Facility for Education: IFFEd[3]) or using other innovative modes of finance.

Over the past few decades, we have seen the Program-Based Approach (PBA) (which uses budget support) gaining momentum due to its advantages in ownership, harmonization and alignment, which are advocated to enhance the effectiveness of aid[4]. Evaluations show, however, that while this modality has been instrumental in reducing the number of out-of-school children and gender disparities, it has yet to prove its effectiveness in improving learning achievement.[5] Meantime, reviews of projects in the education sector that use conditional cash transfers, another new modality, have shown improved enrollment and attendance, but no positive effects on student learning, or even whether they reach the target population.[6] PBA or commonly used aid modalities are not necessarily a panacea for redressing the current learning crisis.

G20 is expected to stress that increases in financial resources should go hand in hand with an evidence-based and informed choice of reform measures that fit their purposes, with room for adjustments to meet local contexts.

Policy Action 2b. Use resources efficiently by ensuring conditions for success

In addition to meeting the pressing needs for financial and other resources to education, it is equally important to pursue wiser ways for using those resources, as well as to develop capacity of the education system to deliver quality services. We experienced “aid fatigue” during 1980s and 1990s that reduced the amount of aid due to lack of visible and lasting aid results. We have to avoid following the same path. Efficiency in the use of available resources is vital and requires good understanding of conditions for success. Limited resources must be used in such a way to maximize their effects.[7] No simple solution has been found for improving learning outcomes, which makes it all the more important to accumulate practical knowledge on what works and how to realize improvements in learning.

G20 should emphasize the importance that due regard be given to the contexts and conditions under which measures have been implemented successfully elsewhere and to adapting them to current cases.

Policy Action 3a. Pool and share knowledge on pathways from intermediate to final results

Influential trends in favor of RBF risk shifting the responsibility for the remaining and most difficult push to achieve the final results. This is because the agreed “results” that trigger release of external resources to recipient governments are in most cases intermediate ones.[8] Moreover, there are no clear-cut solutions to achieving learning outcomes. This means that neither aid recipient countries nor the international community which support them have ready answers. To face this challenge, the international community emphasizes learning assessments (PISA, TIMSS, SACMEQ, EGRA, or national assessment, for instance) as one approach, hoping they will help verify the effectiveness of policy measures or identify enabling factors, or other systemic factors that show promise for improving learning.[9] We have to remember, however, that a conventional input-output model of education production function has been criticized for not presenting a systematic relationship to learning outcomes.[10]

This points to the need to go beyond identifying enabling factors even if they may provide useful hints for targeting investment (“what” to invest in) and combine them with knowledge on the practical process and methods of improving learning (“how” to achieve results). As an illustration, one approach would be to combine knowledge on what key competencies are required in the 21st century with knowledge on how to equip learners with those competencies and what conditions are required for learners to use them as required.

G20 should call upon the international community at large to recognize that such knowledge on pathways to move from intermediate to final results exist globally and locally, and to lead the work of pooling the knowledge for ready reference, to be adjusted to meet local conditions and to be shared among stakeholders through collaboration among the various players.

Policy Action 3b. Develop more useful “outcome” indicators

Correspondingly, G20 should emphasize in its practice of international education cooperation that developing more useful “outcome” indicators is an urgent task.

Take for instance, “the number of teachers who received new in-service training,” used in a real case as one outcome indicator.[11] This assumes that the new in-service training satisfactorily incorporates orientation to the curriculum. It further assumes that those teachers who received the training apply better teaching methods in their respective and more difficult teaching and learning conditions. Input-output actions (curriculum revised, teachers trained) need to be consistently translated along with their embedded concepts (such as student-centered, problem-solving, self-efficacy, etc.) into process actions (teaching and learning practices). Capturing such a complex series of changes in a single “outcome” indicator is an unrealistic challenge, although outcome indicators, once adopted, certainly attract the attention of policy makers sometimes excessively and may thereby unintentionally undermine concerted efforts.

Useful “outcome” indicators for RBF need to be developed and used with other measures so that together they are placed in implementation plans that clearly elucidate actions and considerations to be undertaken concurrently and consistently.

Policy Action 4. Understand the complex reality of the education sector from multiple perspectives

Useful methods have been developed for education planning—analysis of policy issues, identification of solution factors (investment priority), policy appraisal and learning assessment– all of which benefit countries greatly. These methods are mostly crafted outside developing countries, often introduced by international partners who are influenced by certain theories close to them. This can cause the process to be guided by, and to depend on the support by external experts who tend to own most of the knowledge used in the reform process, and who fail to take advantage of valuable opportunities for wider participation, to build the capacity and to ensure ownership of stakeholders.

For instance, education sector planning is guided by parameters (“benchmarks”) which are obtained from cases of countries that have successfully achieved common educational goals.[12] Education sector analysis that justifies international financial support, and that provides a basis for reform agenda setting and clues for solutions is often influenced by external partners. A similar approach is taken to identifying successful models for producing results, as well as for costing the goal framework. However, such approaches may fail to capture other positive or negative consequences of the educational reform agenda, or to respond to the multi-faceted realities behind the issues.

As the educational issues we are tackling become increasingly complex and, therefore, require wider participation of enlarged groups of stakeholders, it is imperative to bring in perspectives beyond conventional analyses.

G20 should gather its voices to highlight the idea that there is great room for using valuable local knowledge and multiple perspectives for analysis, planning and solution of educational problems. Such knowledge and perspectives, used through an inclusive process, will enable us all to understand the complex realities of issues and the entire process of educational development.

Strategy for Implementation

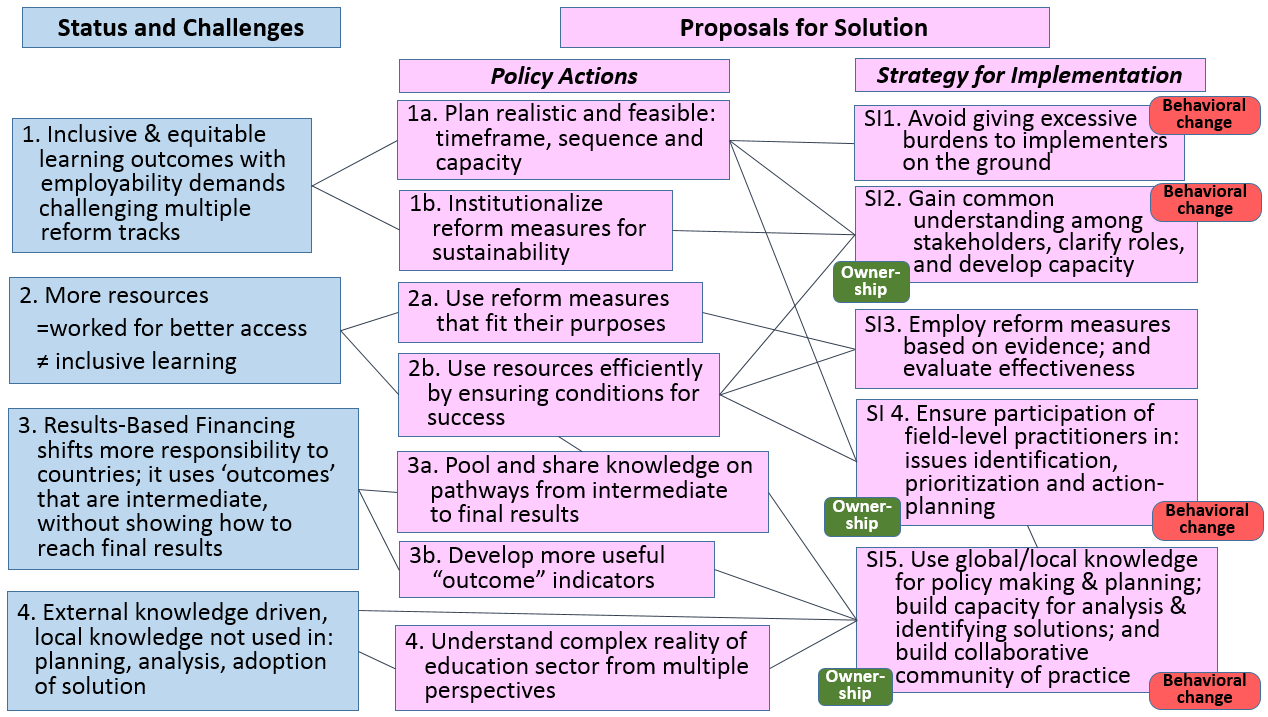

The implementation strategies suggested below do not necessarily correspond to individual challenges and policy actions, but rather need to be considered together as they are closely related to each other, as illustrated by Figure 1.

The G20 should encourage the global community as well as developing country partners to take these strategic actions collaboratively, recognizing their interdependence:

SI1. Realistic and feasible policy planning should carefully consider what additional roles will be created, who will take them on, and who will be asked to accommodate difficult behavioral changes. Policy planning should avoid giving excessive burdens, especially to those who are directly involved with teaching and learning. Invariably, implementation boils down to teachers. Adequate consideration should be given to the sequencing of events.

SI2. It is of paramount importance that stakeholders be identified; that they reach a common understanding of the reform objectives and processes; that their roles be clarified; and they develop the capacity and receive necessary support for implementation (see Box 1).

| Box 1. Institutionalization Matters: The case of Lesson Study in Indonesia[13] Institutionalized reform actions can help bring intermediate outputs to sustained final results, namely, improved teaching and learning in a sustainable manner. Indonesia has successfully fostered the school-based practice of in-service teacher development called lesson study. After jointly discussing classroom challenges, the class is opened to all colleagues and some teachers of other schools. They observe the lesson focusing on learners, and later have reflective discussions to improve teaching and learning. The principal leads this school-wide practice. University researchers who are teacher educators continuously visit schools and provide on-site advisory services. District and provincial education offices have encouraged more schools to practice lesson study, and, seeing its cost-effectiveness and gains in learning, have expanded it to other districts. The initiative began with assistance from JICA, and has continued with the commitment of local stakeholders. The roles of players are clear, mutually stimulating, and objectives are shared. They are centered on collaboration between schools and university, with support of the Ministry of National Education at different levels. What was a small community of practice is now solid and has evolved from the practice in Java with participation of three education universities to the nation as a whole. Eventually a Lesson Study Association of Indonesia was established (2012), which has become a core member of the World Association of Lesson Studies. |

SI3. Reform measures should be employed based on evidence through which their effectiveness is validated. The informed choice of policy measures is made possible when reliable evidence-based information is available on what works for which challenge. Policy borrowing is common on a global scale, and the measures adopted in one country with positive results tend to be employed in other countries. This in turn requires that a systematic evaluation of the intervention has to be embedded in the reform plan of the country concerned.

SI4. Ensuring participation of all stakeholders, primarily field-level practitioners, is indispensable in identifying education policy issues, prioritizing and planning the actions. This will help understanding of complicated realities and conditions for success, and thus make educational plans more realistic and feasible.

SI5. The more complicated and difficult educational challenges are, the more crucial it is that wider groups of stakeholders (including civil society representatives, media and researchers) participate in and contribute to the full cycle of the reform process, with a sense of ownership. This requires building on local and field-level knowledge of policy processes for analyzing issues, gaining insight into and adopting solutions, sequencing events, monitoring and evaluation. Such an approach will help maximize opportunities for building the capacity of stakeholders, and will be instrumental in building a collaborative community of practice. For instance, knowing that a weakness in current practice lies in the monitoring of practices in the field, notably teaching and learning practices that are difficult for indicators to capture suggests that participation of community and NGOs in monitoring teaching and learning might be a good strategy to consider.

Figure1. Transforming Education Financing – Challenges and Proposed Solutions

[1] Gillies (2010) and Verger (2014)

[2] EFA Global Monitoring Report team (2015), Education Commission (2016)

[3] Education Commission (2017)

[4] Riddell and Niño-Zarazúa (2016)

[5] Independent Commission for Aid Impact (2012) and De Kemp, Faust, and Leiderer (2012)

[6] Reimers, DeShano da Silva, and Trevino (2006) and Bauchet, Undurraga, Reyes-Garcia, Behrman, and Dodoy (2018)

[7] Fredriksen (2010)

[8] Yoshidak and Van der Walt (2017)

[9] See, for instance, SABER that The World Bank is leading. https://saber.worldbank.org/index.cfm

[10] Hanushek (2008)

[11] GPE (2015)

[12] UNESCO-IIEP Pôle de Dakar, World Bank, UNICEF and Global Partnership for Education (2014)

[13] Hendayana (2015), Saito, Harun, Kuboki and Tachibana (2006) and Mizuno (2017)