Expanding legal migration pathways is often framed as a panacea to curb irregular migration and mitigate the effects of population aging in immigration countries, while also fostering source countries’ economic development and immigrants’ income. Yet, policy initiatives to expand migration have not gained significant momentum, and available migration windows tend to prioritise highly skilled workers leading to a mismatch between legal admission policies and the average profile of irregular migrants. We propose expanding legal pathways for all skill levels by transforming circular migration into innovative schemes that combine vocational training in home countries with work-related migration opportunities for selected trainees.

Challenge

Immigration countries often frame legal migration pathways as a panacea to stem irregular migration and to counter the workforce decrease caused by population aging. The few existing legal migration windows, however, tend to prioritise admitting highly skilled workers leading to a mismatch between legal migration admission policies and the average profile of irregular migrants. In addition, anti-immigration sentiment is becoming widespread in destination countries, and might increase further following the COVID-19 economic downturn. Policymakers thus face a threefold challenge: (i) expanding legal migration pathways, while simultaneously avoiding the backlash of anti-immigration sentiments; (ii) ensuring that legal pathways are effectively accessible for lowand middle-skilled migrants who tend to move irregularly; and (iii) fostering a good match between the demand for and the supply of skills through labour migration channels.

Against this backdrop, circular migration is frequently advocated as an optimum model for legal migration, providing employers with flexible labour while supporting policymakers’ efforts to control borders. Several international organisations and bodies, for instance, appear to have high expectations about circular migration schemes (CMS) and promote them as a “triple win” migration solution providing gains to countries of both origin and destination, as well as to the migrants themselves (Venturini, 2008; Fargues, 2008; Wickramasekara, 2011; Constant et al., 2012; Castles and Ozkul, 2014). Moreover, circular migrants will not put pressure on destination countries’ social infrastructure, and the latter gain from a reduction in social and political costs associated with immigration. Sending countries, on the other hand, allegedly gain from circular migration through remittances, and from enhanced human capital of the newly acquired skills of returning migrants. Finally, individual migrants gain from increased income while working abroad, and international work experience gives them the opportunity to upgrade their skills and develop their human capital.

However, evidence suggests a disparity between the CMS “triple win” expectations and their present realisation (see e.g., Newland et al., 2008; Wickramasekara, 2011; Castles and Ozkul, 2014; Solé et al., 2016). A recent survey of CMS by Rahim et al. (2021) suggests that a central contributing factor to the “expectation-realisation” gap of CMS is the small-scale nature of contemporary schemes.1 Too few people are involved in recent schemes to have a tangible impact at the aggregate level in origin countries, or in filling labour demand in destination countries. Recruitment of low-skilled workers in CMS could, for instance, alleviate unemployment pressure in source countries, but the small size of contemporary schemes limits their potential development impact. As for high-skilled workers, reducing the brain drain is an important alleged win from circular migration but this claim is contradicted by the fact that immigration countries are competing to attract talents, thereby frequently offering high-skilled immigrants permanent residence status. Therefore, there is a need to develop a new kind of CMS that better meets the “triple win” expectations.

Proposal

The challenges described above suggest a need to expand migration pathways in general, with emphasis on upscaling and transforming CMS. Matching the demand for and the supply of skills through labour migration channels necessitates transforming and designing CMS in a way that will ensure a twinning between circular migration and vocational training initiatives for all skill levels. We propose in particular the expansion of innovative CMS that combines vocational training in home countries and work-related migration opportunities for selected trainees. Policymakers can upscale circular migration pathways by building on existing initiatives for training and migration channels designed to admit lowand middle-skilled migrants, the so-called Skill Mobility Partnerships (SMPs). The latter initially developed to cope with the brain drain consequences of skilled migration combine training and skill formation with international mobility in the form of origin-destination country partnership (Clemens, 2015; Barslund et al., 2019). In an SMP, origin and destination countries jointly provide training programmes to origin country citizens in line with the skill demand in both countries. The trainees, or a part of them, get the opportunity to apply for job opportunities in the destination countries, typically in sectors with high labour shortage.

Analogous to CMS, SMPs are expected to be beneficial for all parties involved. Migrants can earn much higher wages in the destination countries; the destination countries benefit from filling skill shortages at a lower training cost in origin countries,2 and a brain gain occurs in origin countries if the number of trainees exceeds the number of those recruited in the destination countries. Most SMPs were designed to fill labour shortages in nursing and the heath care sector. However, the relevance of SMPs stretches to other sectors, for instance, the training provided by Italy to Tunisians and Moldovans to fill skill shortages in the tourism industry. These examples indicate that distinct from international mobility of the highly skilled or international student mobility the focus of SMPs is rather on professional and vocational training relevant for mediumand low-skilled migrants.

Yet, in spite of their potential, more than five years after the launch of the first SMP proposal (Clemens, 2015), SMPs have not been taken up beyond a small-scale pilot or experimental level. The major obstacles that stand against the expansion of SMPs and prevent their adoption at a large scale include:

– The challenge of soliciting public financial support that focuses primarily on origin countries’ “brain-gain” rather than meeting labour shortages in the destination countries. Privately funded SMPs, on the other hand, are costly for prospective migrants and therefore remain limited to a small number of job opportunities in the destination country.

– The challenge of mobilising the private sector and ensuring its active cooperation in SMP initiatives in origin and destination countries (OECD, 2018). Gaining private sector support for SMP programmes is necessary to avoid skill mismatch and ensure the alignment of training with the employers’ labour demand.

– Low or uncertain transferability of migrants’ newly acquired skills in the destination counties, thus limiting their return to and opportunities in the origin country.

– The difficulty of defining and monitoring a training programme that meets the qualifications and quality requirements in the destination country as well as in the country of origin.

We designate circular migration schemes that connect human capital formation and circular skill migration, and generate vocational training opportunities in migration-sending countries, as “circular skill mobility schemes” (CSMS). Transforming CMS into circular skill mobility allows receiving countries to benefit from an increased supply of skilled workers while at the same time reducing irregular migration. Moreover, CSMS will strengthen human capital stocks in sending countries and thus diminish the skill outflow. The twinning of skill formation and CMS will facilitate addressing the aforementioned listed shortcomings of SMP programmes that deterred their implementation at a large scale. First, circular migration schemes provide the regular migration tracks that SMPs need for their expansion. Second, as circular migration implies a return to the country of origin, all trainees eventually contribute to skill accumulation in the sending country. This eliminates an important obstacle to a higher public facilitation of SMPs, in particular the use of development funds. Third, as circular migration implies recurrent periods of international mobility, migrants in the schemes do not have to fall back solely on opportunities in the country of origin to valorise their skills and experience. Fourth, CSMS would not necessarily require making a distinction between two separate training tracks (for the sending and receiving country respectively). This will substantially simplify training quality monitoring since all trainees will basically share the same programme. Thus, CSMS will guarantee having the same training quality for all participants. Finally, the involvement of the private sector as well as the close cooperation and coordination with the governments (in both sending and receiving countries) will facilitate low search and matching costs for the firms and trainees participating in CSMS.

By expanding legal migration pathways and facilitating labour mobility via CSMS, destination countries will reduce the likelihood of irregular migration and weaken employers’ incentives to fill job shortages with undocumented immigrants. By contrast, policies that restrict workers’ mobility backfire, with workers resorting to risky irregular means of migration or overstaying their visas, and employers hiring undocumented immigrants (Zimmermann, 2014). The immigration policies that restricted the circular flow of workers between Mexico and the US in the 1960-70s, for instance, turned undocumented circular immigrants from Mexico into a population of largely undocumented settled immigrants, without significantly reducing the likelihood of a first trip to the US (Massey et al., 2016). After all, the substitution between legal pathways and irregular migration will depend, inter alia, on the scale of legal pathways and the number of visas issued. There is evidence that a large-scale legal channel for migration between Mexico and the US suppressed irregular migration (Clemens and Gough, 2018).

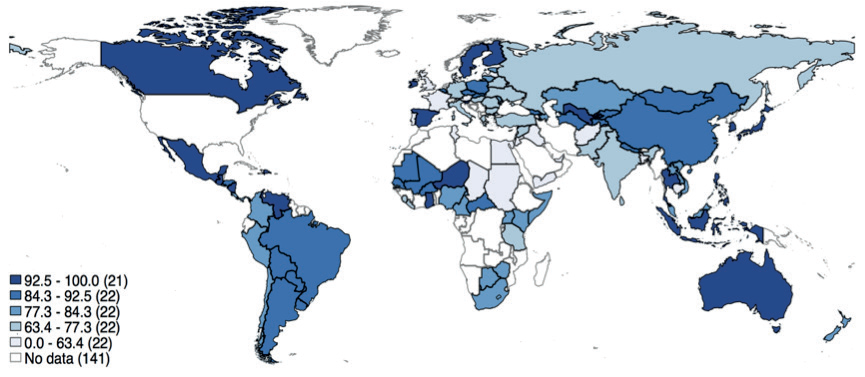

The successful implementation of CSMS, however, will not only require political will but will also depend on (i) the willingness of potential migrants to migrate temporarily (rather than permanently) as well as (ii) the anticipated demand for different skills. With respect to (i), the premise of circular migration is that people have a natural preference for temporary migration. While this claim has been criticised (see e.g., Wickramasekara, 2011), survey information on migration aspirations shows that indeed not all potential migrants would like to migrate permanently (see e.g., Esipova et al., 2011). Using the Gallup World Polls for 112 countries during the period 2009-2012, Rahim et al. (2021) examine the preference of low-skilled respondents (i.e., those who have completed up to primary education) with a desire to migrate for either temporary or permanent migration. The results shown in Figure 1 are compatible with the circular migration conception as prospective migrants have more preference for temporary over permanent migration (the share of low-skilled individuals who prefer to migrate temporarily is over 63 per cent or higher in 87 out of 109 countries for which data were available).

Figure 1: Preference for temporary versus permanent migration by country

Note: Own elaboration based on the Gallup World Poll surveys (waves 2019-2012). The figure shows the estimated share of low-skilled individuals (in per cent) who desire to migrate temporarily among all respondents of the same skill category who expressed a desire to migrate either temporarily or permanently. Low-skilled individuals are those who have completed at most primary education. The sample is restricted to respondents aged 15-50 years.

Yet, with respect to (ii), it might be difficult to accurately forecast how the demand for lowskilled migrant workers is going to evolve in the future as it depends on many factors such as technological progress, natives’ unemployment level and the general macroeconomic situation in the destination and origin countries. However, given population ageing and potential structural labour shortages in the major destination countries, one would expect a rise in the demand for migrant workers. Population ageing is the prominent demographic change that will characterise the 21st century. In their latest projections, the Commission of the European Union forecast a decline in the total EU population of 23 million (5 per cent) by 2070. Labour supply is expected to fall by 16 million people (or 16 per cent) or 0.3 per cent annually (European Commission, 2020). In the paper prepared for the Employment Working Group of the G20 Summit in 2019, the OECD indicated that all G20 countries will be faced with population ageing in the next decades, with the most advanced G20 states at the forefront. At constant labour market participation rates, this would imply an unseen increase in the number of retirees per worker (OECD, 2019).

Further, an increased effort should be undertaken to align the architecture and implementation of the schemes with the Global Compact objectives for orderly migration when designing CSMS. In a recent review of CMS, Rahim et al. (2021) report that most of the surveyed programmes deviate to some degree from the Global Compact for Migration common benchmarks for orderly migration. Such violations are mostly due to employer-tied contracts, lack of social protection and lack of mechanisms to export social security entitlements. These caveats can negatively affect migrant workers’ earnings and the amounts of remittances sent, thereby reducing the aggregate development impact in origin countries. Thus, adopting certain improvements and measures to address these flaws can improve the expected impact of CSMS and make them more acceptable from a liberal point of view. These measures can include, inter alia, aligning CSMS design and implementation with the Global Compact common benchmarks for orderly migration in particular Objective 21 (sustainable reintegration of returnees) and Objective 22 (establishing a mechanism for the portability of social security entitlements) and thereby boosting the expected development impact in origin countries.

Lastly, the G20 in line with its natural initiating and coordinating role is the appropriate forum to review and consider the twinning of skill formation and circular mobility as well as the design of CSMS. Skill shortages and ageing populations are global challenges. Further, for CSMS to expand and reach an operational scale, a global effort and burden sharing is needed. Given that vocational training has a substantial fixed cost component, economies of scale can be obtained by pooling the funds that countries are prepared to allocate. Coordination at a global level is also necessary to avoid free-riding situations where destination countries open their borders to CSMS trainees without contributing to the financing of the schemes. In addition, the G20 is one of the major fora where sending and receiving countries of migration meet. The coordination of the schemes should remain open, swift and flexible, starting from existing CMS and SMPs, as well as schemes to support vocational training in lowand middle-income countries (such as the EU collaboration with Maghreb countries since 2015) (Grand Duché du Luxembourg, 2015). Furthermore, the skill training programmes in the origin countries should be designed based on the skill shortages and demand in both destination and origin countries and consider the legal migration channels to which CSMS connect (such as internships).

NOTES

1 In addition, the disparity between expectations and realisation of the “triple win” potential of CMS also arises from the design of these schemes and the flaws that accompany their implementation (e.g., violation of migrant workers’ rights due to employer-tied contracts, lack of social protection and lack of mechanisms to export social security entitlements).

2 In some case SMPs are implemented in the form of an internship component in the destination country, as in the German dual learning system.

REFERENCES

Barslund, M.; M. Di Salvo; N. Laurentsyeva; L. Lixi; and L. Ludolph (2019), An EU-Africa Partnership Scheme for Human Capital Formation and Skill Mobility, CEPS Project Report

Constant, A.; O. Nottmeyer; and K. Zim merman (2012), “The Economics of Circular Migration”, in IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6940, Bonn, Germany, Institute for the Study of Labor

Castles, S.; and D. Ozkul (2014), “Circular Migration: Triple Win, or a New Label for Temporary Migration”, in Global and Asian Perspectives on International Migration, Springer, Cham, pp. 27-49

Clemens, M. (2015), “Global Skill Partnerships: A Proposal for Technical Training in a Mobile World”, in IZA Journal of Labour Policy, Vol. 4, No. 2

Clemens, M.; and K. Gough (2018), “Can Regular Migration Channels Reduce Irregular Migration”, in Center for Global Development Briefing Notes, February

Esipova, N.; J. Ray; and A. Pugliese (2011), The Many Faces of Global Migration, Gallup World Poll, Gallup and International Organization for Migration Report

European Commission (2020), “The 2021 Ageing Report. Underlying Assumptions and Projections Methodologies”, in European Economy Institutional Papers, No. 141

Fargues, P. (2008), “Circular Migration: Is It Relevant for the South and East of the Mediterranean?”, in Circular Migration Series CARIM Analytic and Synthetic Notes, No. 40

IOM – International Organization for Migration (2018), DTM Middle East and North Africa: North Africa Migrants Profile. DTM Flow Monitoring Survey Results (January 2017 to June 2018), Geneva.

Massey, D. S.; K. A. Pren; and J. Durand (2016), “Why Border Enforcement Backfired”, in American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 121, No. 5, pp. 1557-1600

OECD (2018), “What Would Make Global Skills Partnerships Work in Practice?”, in Migration Policy Debates, No. 15

OECD (2019), Adapting to Demographic Change. Paper prepared for the first meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group under the Japanese G20 Presidency, 25-27 February 2019, Tokyo

Newland, K.; D. Agunias; and A. Terrazas (2008), Learning by Doing: Experiences of Circular Migration, Migration Policy Institute

Lutz, Philipp; and Felix Karstens (2021), “External Borders and Internal Freedoms: How the Refugee Crisis Shaped the Bordering Preferences of European Citizens”, in Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 370-388, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1882541

Rahim, A.; G. Rayp; and I. Ruyssen (2021), “Circular Migration: Triple Win or Renewed Interests of the Destination Countries?” in UNU-CRIS Working Papers

Solé, C.; S. Parella; T. S. Martí; and S. Nita (eds) (2016), Impact of Circular Migration on Human, Political and Civil Rights: A Global Perspective, Vol. 12, Springer

The Expert Council’s Research Unit (SVR Research Unit)/Migration Policy Institute Europe (MPI Europe) (2019), Legal Migration for Work and Training: Mobility Options to Europe for Those Not in Need of Protection, Berlin

Venturini, A. (2008), Circular migration as an employment strategy for Mediterranean countries. CARIM analytic and synthetic notes 2008/39, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Wickramasekara, P. (2011), “Circular Migration: A Triple Win or a Dead End”, in ILO Global Union Research Network (GURN) Discussion Papers, No. 15

Zimmermann, K. F. (2014), Circular Migration, IZA World of Labor