You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Youtube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

We propose a policy package of low-carbon growth stimulation through a steep increase in sustainable infrastructure, mobilizing sustainable finance, and adoption of carbon pricing to simultaneously achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. [1], [2]

Challenge

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) established the scientific foundation of a global consensus that human made climate change poses a very severe threat to development and inclusive growth in the medium and long term. The G20 countries are responsible for roughly 80 percent of global energy use and CO2 emissions, and are thus heavyweight players in climate policy. There are, however, concerns about the distributional effects of some climate policies in combating climate change, and their potentially adverse impact on development prospects and economic growth. These concerns can be resolved through an integrated policy package incorporating the scaling-up of low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure, sustainable finance and carbon pricing.

Despite the collective ambitions that yielded the landmark Paris Agreement, and despite the enhanced commitments to climate action by individual countries embodied in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the world is still far from achieving a collective plan to keep the global temperature increase to well below 2°C. The world is also at risk of being caught in a cycle of low and uneven growth, and, with it, of failing to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to eliminate poverty and provide a better life for all. Unlocking the impediments to the scaling-up of sustainable infrastructure can help to meet all three challenges by laying the foundations for strong and inclusive growth; by providing access to energy, mobility, education and health; and by accelerating the decarbonization of our economies.

This policy brief proposes a comprehensive approach that links inclusive growth, sustainable development and the climate goals. It builds on a sustainable infrastructure with three key pillars: (i) strengthening and reorientation of investment strategies to exploit the significant opportunities of low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure; (ii) transforming finance to enable and drive change; and (iii) phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and putting a price on carbon to harness the transformative power of the market and stimulate low carbon investment.

Proposal

1. Strengthening and reorientation of investment strategies

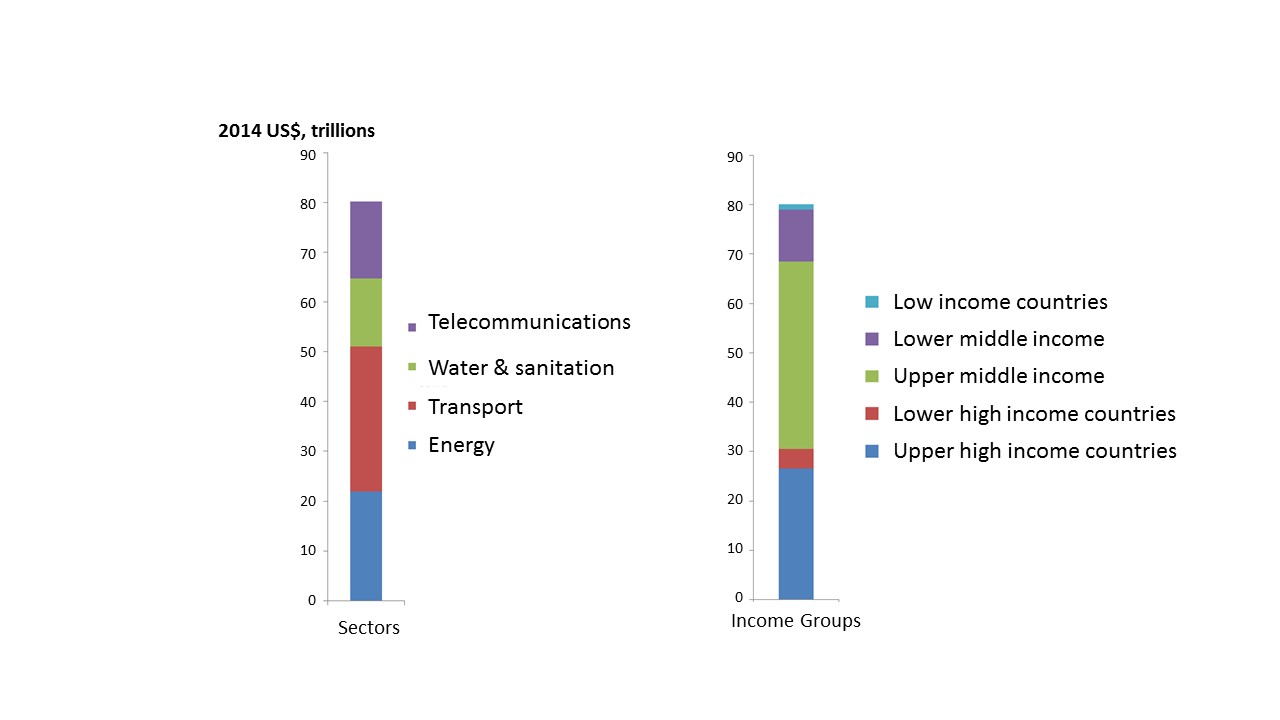

Investment needs for sustainable infrastructure over the next two decades represent a once-in-a-lifetime transition. Rapidly scaling up low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure is key to sustainable development and inclusive economic growth and to meeting the climate goals. The investment required in infrastructure for energy, transport, potable water supply and sanitation, as well as telecommunications over the next 15 years is estimated to be around US$ 80-90 trillion (see Figure 1), which exceeds the value of the entire existing stock. These demands are driven by ageing infrastructure in advanced economies and high demand for new infrastructure in emerging markets and developing countries. New infrastructure demands are growing rapidly because of problems in access to water, sanitation or electricity, rising incomes, and deep structural changes, especially rapid urbanization. Smart infrastructure choices can contribute towards human development in line with environmental targets, whereas making the wrong choices now will result in a lock-in of unsustainable patterns for several decades (see Figure 2 for the example of coal-power plants) and potentially stranded assets[3]

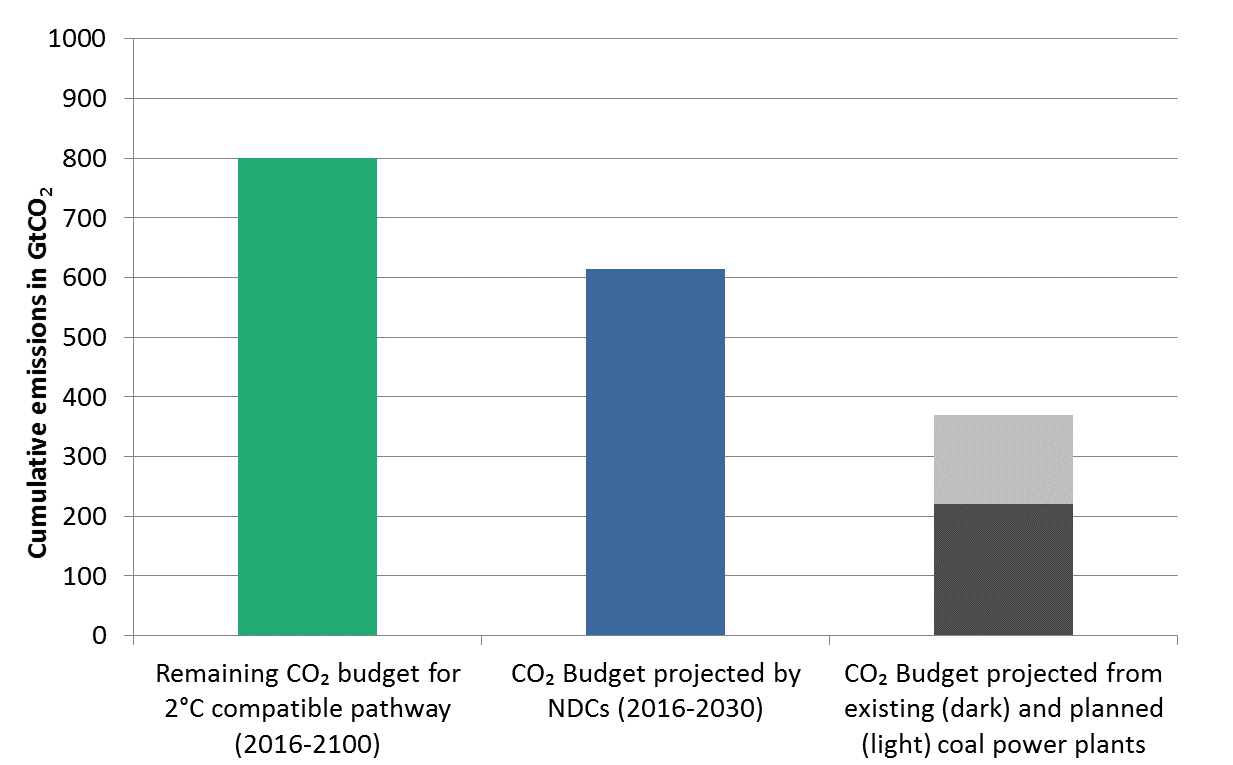

Because of a shrinking global carbon budget, increasing climate risks, and long lived infrastructure assets, the window for making the right choices is narrow. To keep temperature increase to less than 2°C with a ‘likely’ chance, the emission of carbon into the atmosphere needs to be limited to roughly 800 GtCO2. However, the pledged NDCs would consume 75 percent of the total carbon budget by 2030 (see Figure 2). Delay will also increase the cost of future remedial measures and raise the likelihood of catastrophic risks. This underlines the urgency of the problem and the need for stronger action. Building better, smarter and more sustainable infrastructure will allow countries to leverage innovation and continuously strengthen their NDCs in the next decade as required by the Paris Agreement[5]. In addition, making low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure investments today will ensure that decarbonization of the global economy by 2050 remains possible; it avoids locking in high carbon investments and gives policy makers leeway to agree to ambitious targets in the future. In addition, sustainable infrastructure investments can help countries to better prepare for future climate impacts.

Investments in sustainable infrastructure are being held back by an array of impediments that will need to be tackled. Investing in sustainable infrastructure is inherently complex because of externalities (positive and negative) and very long-term horizons. Most countries lack the necessary policy and institutional foundations, including (i) long-term planning capacity (at the national, local and municipal levels) with a focus on sustainability from the outset; (ii) the ability to transform plans into bankable and sustainable projects that internalize positive and negative externalities over the life of the infrastructure; (iii) an enabling environment to attract the private sector including effective Public Private Partnership (PPP) frameworks; (iv) institutional arrangements to underwrite policy and funding risks; (v) overcoming the bias towards incumbent and less sustainable solutions; and (vi) the capacity to plan, build and commission projects efficiently. As a result, there is insufficient infrastructure investment and the investment that is being made is not as smart, resilient and sustainable as it should

- G20 countries should include targets on quantity and quality of sustainable infrastructure consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals and a 2°C compatible pathway within their NDCs, and should recognize infrastructure and investment needs in their long-term climate strategies.

- To support these targets, G20 countries should undertake systematic assessments of current investments and future plans and of the impediments to sustainable infrastructure. Based on these assessments the G20 should set out concrete proposals for national and collective actions to scale up investments and accelerate the shift to low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure.

- The G20 should invite the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) working in cooperation with other international organizations (OECD, IMF, IRENA, IEA and the IEF, and the G20 Infrastructure Hub) and private entities to establish common definitions and standards for sustainable infrastructure that can be used to shape both public and private investments in infrastructure to deliver on a 2°C compatible pathway and the SDGs.

2. Transforming finance to enable and drive change

The scale of investment requirements for sustainable infrastructure calls for a strengthening of finance from all sources and a reorientation towards green and clean infrastructure, because access to long-term and affordable finance is a major barrier to the scaling-up of investments in sustainable infrastructure. Given growing limitations on fiscal space in many countries, stronger efforts are warranted on public resource mobilization including, as discussed below, the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies and adoption of carbon pricing. It will also be necessary to strengthen fiscal capacities at a local level since a large proportion of infrastructure spending will be on urban areas. This will require local governments to access their own sources of revenue and for intergovernmental fiscal relations to give a greater role to cities and local governments.

In order to unlock the capital needed for sustainable infrastructure, policies that leverage the strengths of both the public and private sectors are needed, with the bulk of the financing being generated by the private sector. There are large pools of domestic and global savings that are not currently tapped for green investments. This includes infrastructure. Macroeconomic risks and weaknesses in governance are an impediment to private sector involvement; transforming finance to enable and drive change will require more engagement from the public sector.

The most important impediment to unlocking private sector pools of capital for infrastructure is uncertainty over the reliability of revenues for a given project. Three funding sources can be employed to make sustainable infrastructure projects viable and thereby mobilize private sector green finance: (i) user fees levied on citizens, (ii) availability payments from governments, financed by general or earmarked tax revenues, and (iii) land-value capture levied on project developers. How these funding sources are combined must reflect (i) the ability of users to pay in the short term, (ii) the projected useful life of the infrastructure, and (iii) the timing of spill-over benefits generated by the project. Greater clarity and certainty on how these funding sources will be combined is essential to mobilizing private finance on a large scale.

In addition to contributing to revenue streams to make projects viable, governments themselves may address certain risks. First, governments can reduce regulatory risks through legislative frameworks for carbon pricing, as detailed below, and other regulations to support the achievement of the NDCs. Second, MDBs and public infrastructure banks can provide guarantees for loan tenure risk as well as project-related performance risk for innovative infrastructure solutions. Finally, governments may establish public-private partnerships (PPP) if they prove to provide value for money through strong side-by-side tests to guard against uneconomical PPP arrangements.

MDBs and national development banks have a special role in supporting infrastructure in emerging markets and developing countries, from the policies and institutions that can translate promising ideas into real demand, all the way through to finance at a manageable cost of capital and the effective management of risk. The MDBs and national development banks are absolutely vital in the early stages of these projects to get over the policy and institutional issues and the most difficult of the risks. If these stages are well-managed, large private sector funds can come in.

As part of creating markets to finance sustainable infrastructure and scaled-up deployment of innovation, harmonization of the disclosure of climate-related financial risk throughout the financial system will stimulate a shift of global capital and anchor climate resilience in the global financial system (see T20 policy brief on SMEs and innovation[9]). Information asymmetries related to climate risk make it difficult for investors to assess the physical, regulatory and legal risks of climate change. Today, reporting is voluntary and varies across industries and countries. Mandatory climate-related financial disclosure will guard against the risks of tipping points and contribute to financial stability (see T20 policy brief on Green Finance[10]). These must address three levels of climate-related financial disclosure: (i) how investments contribute to climate change, including the emissions from investment portfolios and low carbon investments, (ii) how climate change will affect the resilience of investments including transition risks and physical risks and (iii) what climate scenario and emissions assumptions are used to assess the climate resilience of investments. For example, only 5 percent of the world’s largest 500 institutional investors have policies in place to actively monitor the risk of stranded assets with their investment managers[11].

Finally, sustainable finance must also be congruent with climate finance as committed under the Paris Agreement. Official development assistance and climate finance remain critical especially for low income and vulnerable countries and can be used to catalyze investments in sustainable infrastructure even in middle income countries. It is important therefore that rich countries live up to their commitments including those made under the Paris Agreement.

Generally accepted standards and definitions of “Green Finance”[12] are crucial to attract investors in sustainable infrastructure. Standardization contributes to building comparable capital markets for investment in sustainable infrastructure across borders and to prevent “green washing” (see T20 policy brief on Green Finance[10]). In addition, climate-related financial transparency is needed in all parts of the financial system including banks, capital markets, institutional investors, private equity managers, insurers, public finance institutions and regulation. Today, even for the institutional investors with the most advanced disclosure policies, only 3.4 percent of their assets represent low carbon investments[11]. This needs to rise significantly if sustainable infrastructure investments are to be scaled-up.

Policies implemented to assure financial system stability must also be considered in light of climate risks to the financial system. Financial market regulation may impede green finance through investment limits, capital adequacy, reserve requirements, the valuation of assets and liabilities and limits on foreign investment. These can discourage longer-term investment and cross-border investments in sustainable infrastructure as well as in emerging innovations. The effect of these regulations can be tempered by allowing preferential capital and equity for sustainable investments. Moreover, platforms encouraging the collaboration between the private sector, regulators, central banks and academics to establish consistent frameworks and definitions across sectors and countries would facilitate the move from voluntary to mandatory disclosure.

The information asymmetries that exist for climate-related financial risk also interfere with projects based on innovative solutions to climate change. These may occur in many areas including, for example, transportation, energy efficiency, renewable energy storage, and methane abatement. In order to accelerate the climate and economic spill-over benefits of public investment in innovation, sustainable finance policies must also address the broadening and deepening of markets for investment in low carbon innovation. This can be achieved by disclosure of the positive impact that investments in these projects have on climate-related financial risk[13] (see also T20 policy brief on SMEs and innovation).

Policy proposals for the G20[8]:

- Building on the commitments made at the Hangzhou Summit, the G20 should ask MDBs to set a system-wide target for supporting the scaling up of sustainable infrastructure consistent with the ambitions of the SDGs and the Paris Agreement. In turn, G20 shareholders should commit to provide MDBs with the resources and flexibility needed to raise their collective ambitions.

- The G20 should invite the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to establish a platform to exchange experiences and develop approaches to disclosure on climate-related financial risks (transition, physical and litigation). This platform should be chaired by finance ministries / central banks and involve all relevant stakeholders, including regulators, academia, finance, industry and relevant international institutions. The proposed platform should develop mandatory climate-related financial risk disclosure as well as its corollary, the potential for risk reduction from investment in sustainable infrastructure and in climate-related innovation projects. In addition, the platform should develop model legislation for financial disclosure and the standardization of green finance practices, for both private-sector and state-owned companies consistent with the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals.

- Fostering the link between Green Finance and carbon pricing: Development Banks and private-sector financial institutions should be encouraged to adopt shadow carbon pricing in internal decision-making as an instrument to help reduce climate-related risk in their investment portfolio. Implicit and explicit carbon pricing should be introduced as an indicator to improve the transparency of green indicators and make “Green Finance” more traceable (see T20 policy brief on Green Finance[10]). G20 governments should also use their leverage to institute shadow carbon pricing throughout MDBs and (semi-)public national banks.

3. Leverage market forces to stem climate change – by setting prices right

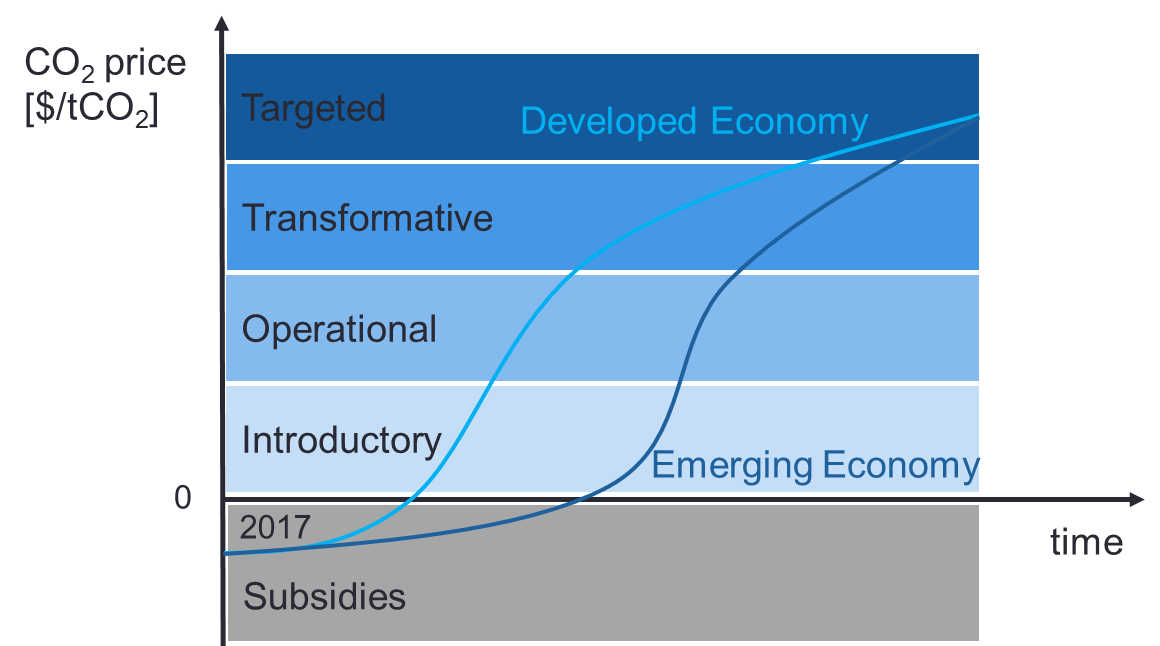

The current price system for carbon favours investment in high-carbon infrastructure for two reasons: (i) fossil fuel subsidies create a perverse incentive for carbon-intensive investments and (ii) there is no price on polluting the atmosphere to steer investments in the right direction. At the global level, every ton of CO2 is subsidized by an average US$ 150 (including negative externalities such as health effects by air pollution)[14] as a consequence of preferential fiscal treatment of carbon industries. By contrast, only 13 percent of global emissions are subject to carbon pricing and the price levels are often low[15]. This incentive structure favours investments in high-carbon infrastructure and disincentivizes low carbon investments. The renaissance of coal, particularly driven by poor but fast growing countries, is one consequence of this perverse incentive structure[16],[17]. A transition towards low-carbon, climate resilient infrastructure requires both the phasing out of inefficient fiscal policies on the one hand and implementing carbon pricing on the other. As a first step, countries can implement carbon pricing schemes at a domestic level, with rising national carbon price plans, depending on whether they are a developed or an emerging economy. They can then converge on a carbon price in the long-term (see Figure 3).

Administrative and political barriers to carbon pricing can be turned into opportunities. Carbon pricing is often perceived to lead to regressive distributional effects and hence to place a greater burden on the poor. While such effects are highly country specific, and in some cases carbon pricing might actually be progressive, potential negative effects for the poor can be addressed through complementary policies (see T20 policy brief on distributional effects of climate policies[18]). For example, Indonesia succeeded in compensating poor households while reforming its fossil fuel subsidy schemes. Complementing fossil fuel subsidy phase out and carbon pricing with support for wider public goods such as health, education, clean energy, and public transport has also proven to increase public support[19].

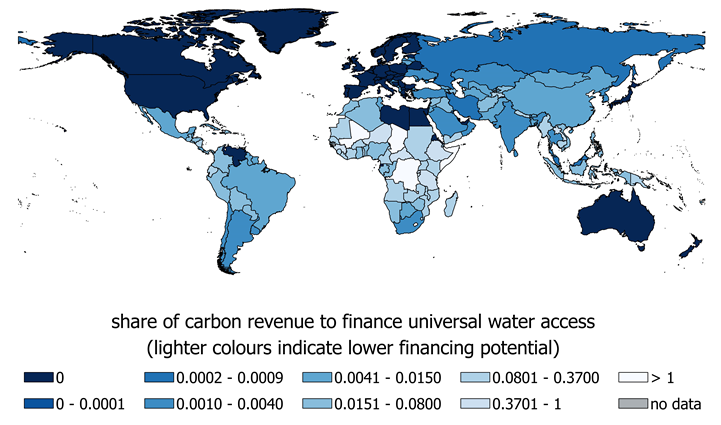

In addition to providing the right incentives for climate change mitigation, getting carbon prices right also generates significant public revenues. These revenues can be used to finance sustainable infrastructure in various ways. First, in most countries, revenues from national carbon pricing schemes, in line with limiting global temperature increase to well below 2°C, would be sufficient to provide universal access to key infrastructure services and thus help to achieve Sustainable Development Goals[21], see Figure 4. Second, carbon pricing may be a lever to increase the economic efficiency of the tax system, especially in economies with large informal sectors, as evading taxes on fossil fuels is less likely than evading sales or income taxes[22]. By substituting income or value added taxes with green fiscal reforms, adverse effects on the poorest members of society can be avoided. Third, carbon pricing revenues can also provide funds for green industrial policies, e.g. to pay emerging firms with climate change solutions for GHG reductions as a bridge to a meaningful price on carbon. Finally, revenues from carbon pricing could serve as a means to ramp up domestic resource mobilization, being one of the main goals stated in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda. Climate finance can play an important role in supporting such national carbon pricing efforts[23].

Policy makers must be equipped with the same quality of information on the low carbon economy as is available for today’s economy. Implementing monitoring systems to track steps towards a low carbon economy will ensure the same quality of economic information that already exists for incumbent fossil-fuel sectors[24]. G20 members must implement long-term low GHG emission and climate-resilient development strategies, in accordance with Article 4 of the Paris Agreement, supplemented by reliable metrics to track progress (see T20 policy brief on establishing an Expert Advisory Commission)[25]. To determine whether developments are in line with stated targets, they should be made subject to regular rounds of peer-review, as is already common practice in numerous international fora.

Policy proposals for the G20[8]:

- Assess the adequacy of carbon prices: The G20 Finance Ministers should commit to a peer review process to assess the adequacy of the current carbon pricing systems to deliver the Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement.

- Phase out fossil fuels subsidies: The G20 have pledged, every year since 2009, to phase out fossil fuel subsidies, but have not set a specific deadline to do so. We suggest that the G20 members should now set 2022 as a target date for eliminating fossil fuel subsidies, including both production and consumption subsidies. This should be accompanied by redirecting the savings towards groups most affected by the reform. In addition, all G20 members should complete their fossil fuel subsidy peer reviews by 2018.

- Develop a carbon pricing roadmap: A permanent platform for cooperation on carbon pricing within the G20 should be established with the aim of (i) developing a roadmap to implement carbon pricing to double the level of emissions covered by carbon pricing mechanisms from current levels of about 17 percent within the G20 to 35 percent by 2020, and doubling it again within the following decade, (ii) agree on a minimum carbon price that should grow over time to become transformative, (iii) underpin bilateral endeavour and mutual peer-review of carbon pricing systems, and (iv) price carbon broadly, while maintaining social equity and increasing access to sustainable infrastructure, to ensure a just transition towards a low-carbon economy.

References

- This policy brief is a joint product by all members of the Task Force Climate Policy and Finance (see [2]) and draws on joint discussions at the workshops on 3.12.2016 and 28.02.2017. It is lead-authored by the Co-Chairs Céline Bak, Amar Bhattacharya and Ottmar Edenhofer and by the coordinator of the Task Force Brigitte Knopf. It benefited considerably from input by Jan Steckel, Michael Jakob, Olivier Bois von Kursk, and Gregor Schwerhoff, from MCC.

- Members of the Task Force are (Name, Surname, Institution, Country): Alan S. Alexandroff (Munk School of Global Affairs / University of Toronto, Canada), Venkatachalam Anbumozhi (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), Indonesia), Daniel Argyropoulos ((Agora Energiewende), Germany), Steffen Bauer (German Development Institute (DIE) Germany), Kathrin Berensmann (German Development Institute (DIE) Germany), Ralph Bodle (Ecologic, Germany), Olivier Bois von Kursk (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Kerstin Burghaus (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Will Burns (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada), Ben Caldecott (Oxford Smith School, United Kingdom), Carraro Carlo (International Center for Climate Governance (ICCG), Italy), Elie Chachoua (Climate Action Network-International (CAN), France), Romy Chevallier (South African Institute of International Affairs), South Africa), Neil Craik (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada), Ira Dorband (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Susanne Dräger (CDP, Germany), Susanne Dröge (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Germany), Egenhofer Christian ((CEPS), Belgium), Jasper Eitze (Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Germany), Sam Fankhauser (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, United Kingdom), Manfred Fischedick ((Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie) Germany), Oonagh Fitzgerald (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada), Andrés Flores (Centro Mario Molina, Mexico), Philipp Großkurth ((RWI – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research), Germany), Gerrit Hansen (Germanwatch, Germany), Tom Heller (Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), USA), Ingrid Holmes (E3G, United Kingdom), Yu Hongyuan (Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (SIIS), China), Mike Jakob (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Ye Jiang (SIIS, China), Frank Jotzo (Australian National University, Australia), Kastrop Christian (OECD, Germany), John Kirton (Munk School of Global Affairs / University of Toronto, Canada), Madeline Koch (Munk School of Global Affairs / University of Toronto, Canada), Andreas R. Kraemer (Ecologic Institute; Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Germany), Gabriel Lanfranchi (Center for the Implementation of Public Policies Promoting Equity and Growth (CIPPEC), Argentinia, Le Pere Garth (University of Pretoria, South Africa), Gerd Leipold ((Humboldt-Viadrina Governance Platform; Climate Transparency), Germany), Wonhyuk Lim (KDI School of Public Policy, Korea), Domenico Lombardi (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada), Andreas Löschel (University of Münster, Germany), Melissa Low (National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore), Lawrence MacDonald (World Resources Institute (WRI), USA), Gustavo Martinez (Council for International Relations (CARI), Argentinia), Sylvie Matelly (Istitut des Relations International et Strategique (IRIS), France), Mercedes Mendez Ribas (Center for the Implementation of Public Policies Promoting Equity and Growth (CIPPEC), Argentinia), Nils Meyer-Ohlendorf (Ecologic Institute, Germany), Cao Mingdi (Renmin University of China (RDCY), China), Susanna Mocker (Agora Energiewende, Germany), Leif Moestue (Center for the Implementation of Public Policies Promoting Equity and Growth (CIPPEC), Argentinia), Shingirirai Mutanga (Human Science Research Council (HSRC), South Africa), Hermann Ott (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie (WI), Germany), Jyoti Parikh (Integrated Research and Action for Development (IRADe), India), Anna Pegels (German Development Institute (DIE), Germany), Sonja Peterson (Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), Germany), Kamleshan Pillay (BRICS Research Centre, South Africa), Yang Qingqing (Renmin University of China (RDCY), China), Rainer Quitzow (IASS, Germany) Sybille Röhrkasten (IASS, Germany), Joel Ruet (The Bridge Tank, France), Güven Sak (The Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV), Turkey), Thilo Schäfer (Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Koeln (IW), Germany), Hannah Schindler (Climate Transparency, Germany), Gregor Schwerhoff (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Gaurav Sharma (Observer Research Foundation (ORF), India), Thomas Spencer (Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales (IDDRI), France), Jan Steckel (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC), Germany), Ulf Sverdrup (Norwegian Institute for International Affairs (NUPI), Norway), Sonja Thielges (IASS, Germany), Tian Huifang (CASS-IWEP, China), David Uzoski (International Institute for Sustainable Development, Switzerland), Laurie van der Burg (Overseas Development Institute (ODI), United Kingdom), Eike Velten (Ecologic Institute, Germany), Elena Verdolini (Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei and CMCC, Italy), Ernesto Viglizzo (Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI), Argentina), Ulrich Volz (German Development Institute (DIE), Germany), Olaf Weber (Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Canada), Shelagh Whitley (Overseas Development Institute (ODI), United Kingdom), Peter Wolff (German Development Institute (DIE), Germany)

- Röhrkasten, S., Kraemer, R.A., Quitzow, R., Renn, O., Thielges, S. (2016):

An Ambitious Energy Agenda for the G20. Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) - Bhattacharya, A., Meltzer, JP., Oppenheim, J., Qureshi, Z., Stern, N. (2016):

Delivering on Sustainable Infrastructure for Better Development and Better Climate. - Bak, C. (2016), Growth, Innovation and COP 21:

The Case for New Investment In Innovative Infrastructure, Centre for International Governance Innovation - IPCC Climate Change (2014): Synthesis Report, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- Edenhofer, O., Flachsland, C., Kornek, U. (2016): Der Grundriss für ein neues Klimaregime, ifo Schnelldienst, 3/2016, 69. Jahrgang, 11-15

- Our analysis is based on peer-reviewed literature, as given in the references. The recommendations are based on the evidence of this literature, but are personal opinions of the authors.

- Verdolini, E., Ruet, J., Venkatachalam, A., Bak, C. (2017): Low carbon innovative SMEs as an opportunity to promote financial de-risking, T20 Climate Policy and Finance Taskforce (2017)

- Berensmann, K., Volz, U., Alloisio I., Bak, C., Bhattacharya, A., et al. (2017): Fostering sustainable global growth through green finance – what role for the G20?, T20 Task Force on Climate Policy and Finance

- Global Asset 500 Index 2016 (2016): Rating the world’s investors on climate related financial risk, Asset Owners Disclosure Project

- Green Finance can be understood as the financing of investments that provide environmental benefits in the broader context of environmentally sustainable development (G20 Green Finance Study Group). It was brought forward in the G20 context during the Chinese presidency in 2016.

- Bak, C. (2017):

Generating Growth From Innovation for the Low-Carbon Economy: Exploring Safeguards in Finance and Regulation, Centre for International Governance Innovation - Coady, D., Parry, I., Sears, L., Shang, B. (2015):

How Large are Global Energy Subsidies? IMF working paper. - World Bank; Ecofys; Vivid Economics (2016):

State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2016. Washington, DC, - Steckel, JC., Edenhofer O., Jakob M. (2015): Drivers for the renaissance of coal. PNAS 112(29):E3775–E3781.

- Edenhofer, O. (2015): King Coal and the Queen of Subsidies, Science, Vol. 349, Issue 6254, 1286-1287

- Dao Nguyen, T., Edenhofer, O., Grimalda, G., Jakob, M., Klenert, D., Schwerhoff, G., Siegmeier J. (2017): Distributional effects of climate policy, T20 Task Force on Global Inequality and Social Cohesion

- Whitley, S., van der Burg L. (2015):

Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform: From Rhetoric to Reality, New Climate Economy, Working Paper. - Carbon Disclosure Project CDP (2015):

Carbon pricing pathways. Navigating the path to 2°C. - Jakob, M., Chen, C., Fuss, S., Marxen, A., Rao, N., Edenhofer, O. (2016): Using carbon pricing revenues to finance infrastructure access. World Development

- Franks, M., Edenhofer, O., Lessmann, K (2015): Why Finance Ministers Favor Carbon Taxes, Even if They Do Not Take Climate Change into Account, Environmental and Resource Economics.

- Steckel, J.C., M. Jakob, C. Flachsland, U. Kornek, K. Lessmann & O. Edenhofer (2017): From climate finance toward sustainable development finance. WIRE Climate Change Vol 8 Issue 1

- Bak, C. (2015): Growth, Innovation and Trade in Environmental Goods. Centre for International Governance Innovation, CIGI Policy Brief No. 67

- Löschel, A., Großkurth, P., Colombier, M., Criqui., Dexion, S., Furuhata, K., Gethmann, CF., et al. (2017): Establishing an Expert Advisory Commission to assist the G20’s Energy Transformation Processes. T20 Task Force on Climate Policy and Finance.