The current debate on global inequality and social cohesion has also recognized growing differences in living standards between urban and rural areas. This policy brief discusses factors contributing to the urban-rural divide and recommends policies to facilitate the process of catching up. It stresses the megatrends of globalisation and digitalisation in explaining agglomeration in urban areas. Digitalisation and weak connectivity can further exacerbate urban-rural disparities. The policy brief concludes with a set of measures that helps rural areas catch up and contributes to inclusive economic growth. The proposed policies emphasize the need to foster social cohesion in the digital transformation.

Challenge

The recent rise in income inequality has been a key factor in the debate on social cohesion. Consequently, policy makers have been discussing taxation, education, welfare state policy and other areas to keep greater dispersion in people’s incomes at bay. However, the rise in income inequality has perhaps masked a distinct, yet equally worrisome, development: the increasing disparities between urban and rural areas. More than half of the population today lives in urban areas – in 1950, it was only about a third. By 2050, the share will be at two thirds according to figures from the World Bank (2018). Even though there exists no standardised classification defining urban, rural or semi-urban and peri-urban areas (United Nations, 2018), we observe a global tendency of economic activity shifting towards big cities and metropolitan areas – at the expense of rural areas with a much lower population density. This development does not just change the way people live together. It could also exacerbate income inequality. Data by the OECD (2018a) appear to support this view: While income differences between countries have narrowed, differences between regions within countries have dramatically increased.

Importantly, such regional disparities are not confined to emerging economies. Advanced economies also experience a tendency of its population to concentrate on major cities and thriving regions. According to a European Parliament study, one in three regions in Europe will experience a population decline over the 2008-2030 period (Eatock et al., 2017). In Europe, significant demographic shifts within countries created a core-periphery pattern, both in the EU and within member states. Strong population growth can be observed in eastern Ireland, the southern part of the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and in megacities such as Paris and London. Parts of western Germany also seem to have benefited from population growth, as have northern Italy and Scandinavia. At the same time, areas mostly located in central Europe, eastern Germany, southern Italy and northern Spain are projected to lose parts of its population.

As a result, rural areas not only tend to have fewer residents. GDP per capita is also lower than in their urban counterparts. The Eurostat’s 2016 State of European Cities report points out that high-income cities in Europe have generated the highest GDP and employment growth – which stems from cities’ stronger influx of relatively young citizens as well as migrants searching for education and job opportunities. This, in turn, leads to stronger population growth in cities – and economic theory suggests that an expansion of the labour force is one factor driving economic growth besides a surge in the capital stock and productivity. As a consequence, the gap in average incomes between urban and rural areas widens.

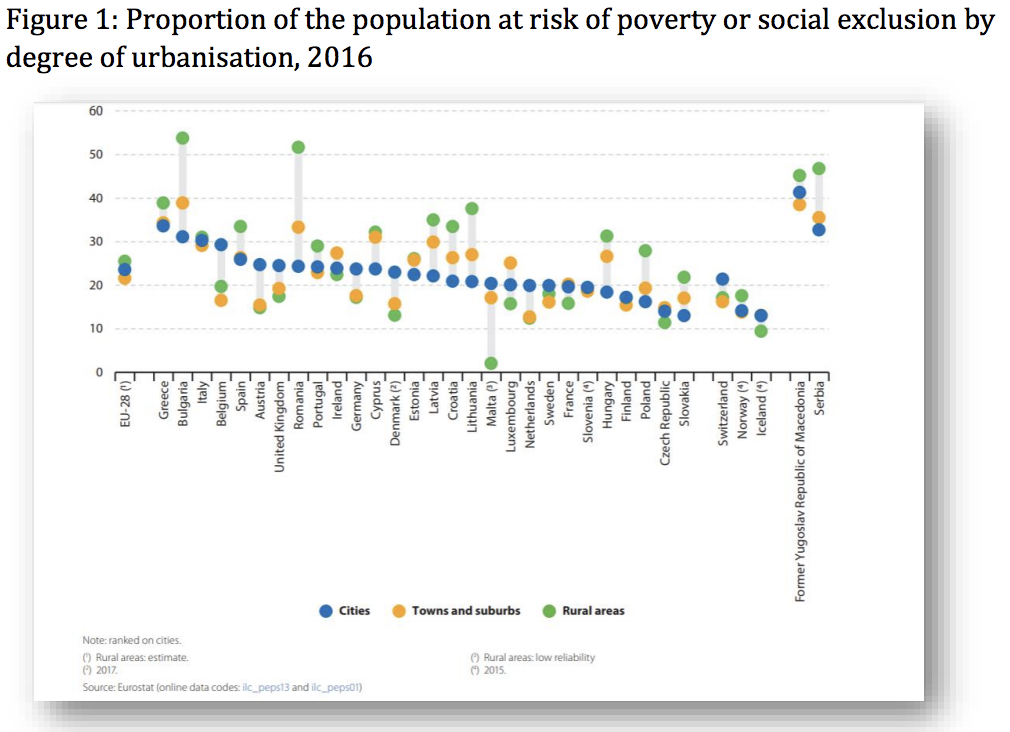

A closer examination reveals that in half of the EU Member States, rural areas feature the highest proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (see Figure 2). In Bulgaria and Romania, more than half of the rural population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016. Similar patterns prevail in Greece, Lithuania, Latvia, Croatia, Spain, Cyprus, Hungary and Italy, where the risk was within the range of 30 to 40 percent (Eurostat, 2018). Data from the Economist (2011) show that these issues are not exclusive to Europe. They exist in other countries, too.

How did regional disparities emerge?

The reasons for increasing regional disparities are manifold and still subject to research. But two factors already stand out, the megatrends of globalisation and digitalisation. Both of these trends have favoured agglomeration in urban areas: fiercer competition due to globalisation has led to greater specialisation of industries, where increased agglomeration exhibits greater returns to firms and larger gains from economies of scale. In addition, urban areas are better connected to hubs in other countries – as globalisation has generally decreased the cost of multilateral trade, it is now even more attractive for firms to locate in better connected urban regions (WTO, 2018). Also, increasingly digitalised business models benefit from agglomeration in urban areas. Digitalisation generally favours high-skilled labour at the expense of low-skilled labour – and the former has increasingly moved to larger cities. Finally, increasing political and social urban-rural cleavages determine elections and have thus become an important factor shaping political behavior and electoral competition.

Agglomeration has also led to a stronger spatial polarisation of economic activity. A study by the McKinsey Global Institute finds that 50 cities account for eight percent of the global population, 21 percent of world GDP, 37 percent of urban high-income households, and 45 percent of headquarters of firms with more than $1 billion in annual revenue (Manyika et al., 2018). The average GDP per capita in these cities is 45 percent higher than that of comparable cities in the same region and income group, and the gap has grown over the past decade. Most of these “superstar” cities are economic hubs, political centres and gateways to trade, finance, data and talent flows. Economies of scale and agglomeration effects allow them to outperform other cities. Similar patterns have been observed in so-called “superstar” firms that are typically prevalent in urban hubs. Pull factors such as superstar cities and firms attract highly educated, young people. Consequently, urban-rural disparities go hand in hand with demographic change, thereby aggravating productivity and employment dynamics.

The evolution of future technologies could exacerbate urban-rural disparities.

An OECD study suggests that in rural areas more jobs are at high risk of automation (OECD, 2018b). Although automation in itself is a source of higher productivity, it forces the labour market into transformation. In some OECD regions, the risk of losing a job due to automation amounts to almost 40 percent (mostly eastern Europe), while it remains as low as four percent, in regions around Oslo for example. Low skilled workers may struggle to find new jobs, while jobs in cities are mostly placed in the tertiary sector, require a better education and tend to be more resilient to automation. Thus, the uneven impact of automation can widen inequality in employment conditions between urban and rural areas.

Moreover, weak digital connectivity could further aggravate the outlook in rural areas. According to Eurostat (2015), for all but three of the EU Member States, people living in rural areas are less likely to make use of the internet on a daily basis. People there are on average less educated and less wealthy, and might face language and cultural barriers preventing them from access to the internet. For many companies, this might not pay off. The World Economic Forum (2014) calculated that each additional 10 percent of internet penetration could lead to a 1.2 percent increase in per capita GDP growth in emerging economies. Without digital infrastructure, rural areas stay behind.

The population in rural areas is also more cut-off from access to public services compared to their urban counterparts. The European Quality of Life Survey 2016 points out that differences between urban and rural areas are most significant for access to public transport: While only eight percent of people living in urban areas report problems in accessing public transport, this is reported by more than half (55 percent) of respondents living in rural areas. Disparities are equally visible when asked about the access to cultural facilities (19 percent versus 58 percent), access to banking facilities (15 percent versus 27 percent) and grocery shops (five percent versus 21 percent). Health is a case in point: as generally more doctors practice in urban and capital regions and/or those that are socio-economically better off, rural, remote or poorer regions face bigger challenges with regard to healthcare provision (OECD, 2016). For these services, access problems generally worsen gradually with rurality: Relatively fewer people live in rural areas and thus demand remains low. However, if rural residents lack basic infrastructure, the prospects of catching up remain low and even potentially productive areas might experience low productivity growth. All of the above factors contribute to an urban-rural divide which can, in turn, shape identity politics. This can currently be observed in advanced economies, but also in emerging ones such as India. To facilitate an inclusive catching up process, well targeted policies are needed.

Proposal

Across countries, laggard regions face the same challenge: digital innovation, growth and productivity cannot compete with that of urban hubs. Thus, policy making should foster economic development in these areas. A number of recommendations are well suited to achieve this goal.

1. Foster innovation policies in rural areas

Governments should specifically target innovation policy at rural areas. The creation of an ecosystem of innovation in rural areas is particularly useful. First, it should entail cooperation between university and firms to generate innovations that can be used by regional industries. Second, it could foster the creation of a start-up industry in rural areas. Start-ups are very innovative when it comes to digitalisation. Moreover, they attract the young to rural areas, thereby creating a more favourable demographic outlook. At the same time, targeted SME strategies are needed to maintain the backbone of strong and sustainable growth in an economy. All these measures would be aimed at increasing the pace of innovation in rural areas – which would translate into higher productivity and GDP growth in these regions (OECD, 2018c).

Recommendation: G20 member states should enact policies that support innovation and start-up eco-systems in rural areas.

2. Upgrade digital infrastructure and connectivity

Urban-rural disparities become especially evident when it comes to digital infrastructure and connectivity, as rural areas clearly lag behind. Despite the growing importance of cities, governments must not de-prioritise the provision of digital infrastructure in rural areas. Quite the contrary: Policy makers must ensure that digital infrastructure is also available in rural areas – otherwise, businesses and skilled workforce alike will not settle in such regions. G20 member states have committed to tackle the digital divide in the Hangzhou Communiqué. More investment in transportation in (and between) rural and urban areas is needed. Sustainable and affordable means of public transport are as essential as digital connectivity and help strengthen community and business links between urban and rural areas.

Recommendation: G20 countries should commit to increased spending goals for digital infrastructure and connectivity in rural areas.

3. Create opportunities for upskilling

The workforce in rural areas is often cut off from upskilling opportunities needed to be competitive in an increasingly digitalised economy. Many in the workforce are not mobile enough to move to urban areas in order to attain these skills. Moreover, it will economically benefit rural areas if its workforce has attained a higher skill level. Finally, academic research suggests that educational institutions in itself can boost economies in rural areas as they exhibit positive spill-over effects by increasing local demand for goods and services and can attract younger individuals from elsewhere (OECD, 2018c).

Recommendation: G20 countries need to develop and implement strategies to improve the skill-level of the workforce in rural areas.

4. Provide social protection

Economies face structural change that benefits urban areas at the expense of rural areas and exacerbates the gap between the two sets of regions. One example is agriculture, the economic importance of which has declined, and which is sparsely prevalent in urban areas. The workforce in agriculture may receive training useful to other occupations, but for some individuals it may not be feasible and in general, adjustments by the workforce take time. In the meantime, it is paramount that the welfare state supports citizens as the last line of defence. In this context, the welfare state should consider measures like working tax credits and other means to support individuals on low incomes.

Recommendation: G20 member states should commit to a welfare state targeted at those with most difficulty to adjust to structural changes in the economy.

These four measures, along with other conceivable policy responses, can contribute to an economic empowerment of rural areas and more social cohesion. These potential benefits can safeguard the G20 member states from citizens’ disappointment with governments and even the rise of social unrest. Finally, they can all jointly contribute to the goal of inclusive economic growth.

References

1. Eatock, D. et al. (2017). Demographic Outlook for the European Union. European Parliament Research Service (EPRS). Retrieved from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2017/614646/EPRS_IDA(201 7)614646_EN.pdf

2. Eurofound (2017). European Quality of Life Survey 2016: Quality of life, quality of public services, and quality of society. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg. Retrieved from: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/europeanquality-of-life-surveys/european-quality-of-life-survey-2016

3. Eurostat (2015). Statistics on rural areas in the EU. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php/Statistics_on_rural_areas_in_the_EU

4. European Commission, UN Habitat (2016). The State of European Cities Report. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/citiesreport/state_eu_cities2016_en.pdf

5. Gaponomics (2011, March 10). The Economist. Retrieved from: https://amp.economist.com/leaders/2011/03/10/gaponomicsG20 (2016). G20 Leaders’ Communique.

6. G20 Leader’s Communiqué: Hangzhou Summit, 4-5 September. Retrieved from: https://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2016/160905-communique.html

7. Manyika, J., Ramaswamy, S., Bughin, J. et al. (2018). ‘Superstars’: The dynamics of firms, sectors, and cities leading the global economy. McKinsey Global Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and

8. OECD (2018a). OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/reg_cit_glance-2018-en

9. OECD (2018b). Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2018: Preparing for the Future of Work. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305342-en

10. OECD (2018c). Rural Policy 3.0. A framework for rural development. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Rural-3.0-Policy-Note.pdf

11. OECD (2016). Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places, OECD Health Policy Studies. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264239517-en

12. United Nations (2018). The speed of urbanization around the world. Population Facts. No. 2018/1. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/Po pFacts_2018-1.pdf

13. World Bank (2018, October 5). Urban Development Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview

14. World Economic Forum (2014). Delivering Digital Infrastructure Advancing the Internet Economy. Retrieved from: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TC_DeliveringDigitalInfrastructure_InternetEco nomy_Report_2014.pdf

15. World Trade Organization (WTO) (2018). The future of digital trade: How digital trade technologies are transforming global commerce. WTO Publications. Geneva. Retrieved from: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/world_trade_report18_e.pdf