The World Trade Organization (WTO) faces an existential crisis and its main functions are eroding. Its rulemaking function must be revised to govern the current trading environment. Its dispute settlement system, particularly the Appellate Body, has been deadlocked; the impasse must be resolved. Leading stakeholders have presented several reform proposals; however, the main challenge comes from systemic issues embedded in the geopolitical rivalry among major Group of Twenty (G20) members. The reform is not an easy process in a member-driven institution where consensus is strictly required. The G20 represents a critical mass of world trade and must play a collective leadership role with deliberate dialogue in order to provide a coherent approach that identifies divisions and creates solutions. This policy brief provides recommendations for the initial steps that the G20 can take to support WTO reforms.

Challenge

Despite its initial successes, the World Trade Organization (WTO) currently faces an existential crisis. There are calls for substantial reform as the organization’s main functions are progressively becoming ineffective. Other than notable initiatives, it has not provided an effective forum for trade negotiations for more than a decade.[1] Its rules have not adequately adapted to global economic dynamics and its rulemaking procedures require revisions. The WTO’s most successful contribution, adjudicating trade disputes, has run into difficulty: the organization’s Appellate Body (AB) has been paralyzed by a disagreement regarding the appointment of new judges to fill vacancies. The trading system shows signs of stress on many fronts (Akman et al. 2020).

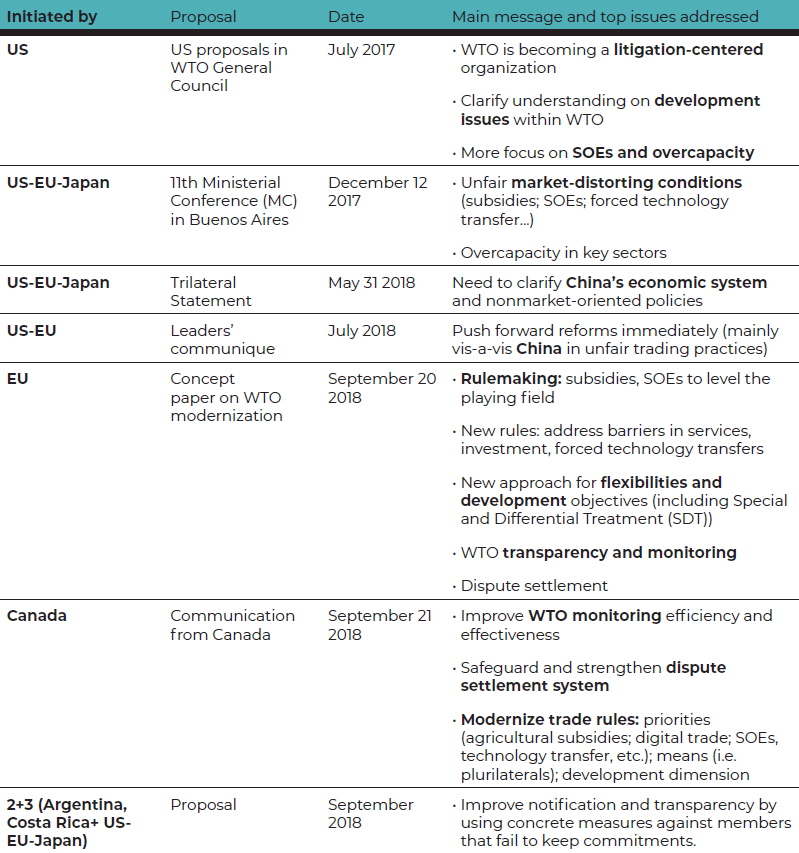

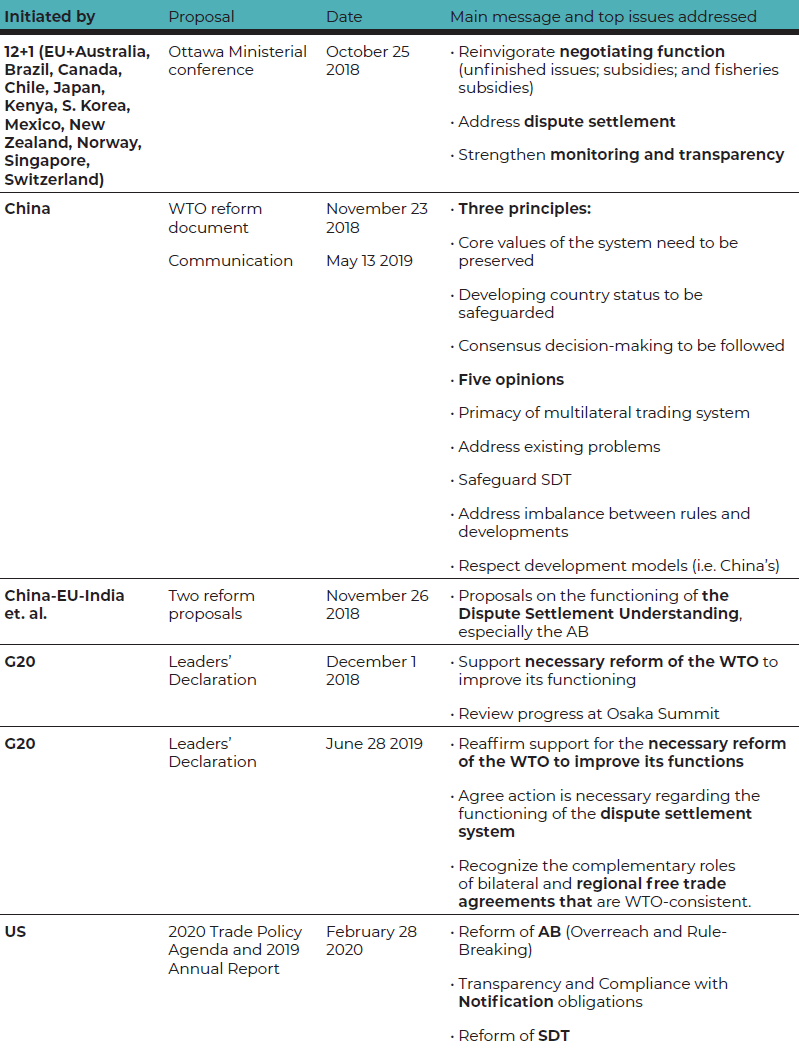

The stakeholders and policy community argue that reforming the WTO system is inevitable. Several proposals by leading WTO members have emphasized challenges in the WTO’s functioning (see Table 1); at the same time, this reflects confrontational issues embedded in a changing geopolitical landscape (Felbermayr 2020, 71). The rivalry between market-oriented and state-oriented economic systems is at the core of the divide. The trading system is expected to provide a new rulebook in several areas, including market-distorting conditions and coping with increasing trade protectionism.

With the transformational change in the global economy, the WTO is expected to become more responsive to external imperatives in governing trade. Issues like digital trade, investment facilitation, regulatory cooperation, climate-trade linkage and other trade-related concerns require focus (Hahn 2019, 131). The COVID-19 pandemic has also created added uncertainties in trading environments as countries implemented new restrictive policies regarding essential supplies (Evenett 2020), making the WTO’s role pertinent in protecting global trade from the pandemic’s effects. Meanwhile, the WTO is currently facing difficulties in managing its operational activities and the selection of its new Director-General under social distancing conditions.

The reform proposals by major trading nations also note that the WTO system faces internal difficulties. Running a member-driven and complex organization based on consensus is no longer practical. Achieving consensus through innovative methods, such as plurilaterals and regional agreements, is equally important and can facilitate the functioning of the multilateral system.

The Group of Twenty (G20) represents a critical mass of world trade and system challenges. The G20 members must play a collective leadership role in providing a coherent approach that identifies differences and priorities while finding solutions to facilitate the WTO’s functioning and the multilateral trading system. The G20 should also attend to the WTO’s role in mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic’s negative impacts on global trade.

Table 1. Major Proposals for Reforming the WTO

Proposal

Before advancing to recommendations, further elaboration is needed on major issues raised in WTO reform proposals as well as an assessment of alternative courses of action that WTO and G20 members currently use to address challenges.

Two Confrontational Issues

Overall, reform proposals focus on three aspects of the WTO’s functioning: rulemaking; transparency and monitoring; and dispute settlement. Two major issues stand out: (1) the status of developing countries, that is, Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) and (2) market-distorting free-floating policies regarding state involvement, mainly targeting China.

I. The Development Debate and SDT

Developing country status is self-defined rather than through objective criteria. The SDT became a controversial issue as many developing countries started to more firmly integrate into the world economy and receive larger shares of global trade.

The 2019 US Memorandum referring to this issue (White House 2019) suggests concrete measures, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and purchasing-power parity, membership in the G20 and OECD, and shares in global exports and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). However, the criteria should also consider social and human development indicators created by international organizations, which should receive a multilateral approach.

II. Market-Distorting Conditions

The rising discontent from advanced economies is largely driven by the perception that the WTO framework allows differences in regulatory regimes and that it needs to level the playing field. Some members are regarded as implementing “state capitalism,” enabling market-distorting practices such as subsidies, state-owned enterprise (SOEs), forced technology transfer policies (Marvroidis and Sapir 2019, 43),[2]and disregarding labor and environmental standards. These concerns are largely discussed in the Trilateral initiative.[3] The issue is challenging for global trade. However, confrontations between two major systems need to be resolved through multilateral platforms rather than implementing unilateral measures.

Alternative Courses of Action

To counter the challenges faced, WTO members have applied four major courses of action:

1. The WTO’s Dispute Settlement Mechanism

The dispute settlement mechanism (DSM) in the WTO was attractive as members’ interest in adjudicating trade disputes within the WTO increased. However, the DSM currently faces numerous challenges including delays in the adjudication process and disagreement over the AB’s competence. The debate over the mechanism and the AB rose as legislature (WTO members) failed to clarify the rules. The number of cases under DSM proliferated, and judgments were delivered “under ambiguity of the extant rules” (Bhagwati, Krisha, and Panagariya 2014, 24).

2. Non-Multilateral Tracks

Regional trade agreements (RTAs) are avenues that aim to liberalize trade as well as create new rules and disciplines to address challenges of the global trading system. However, these initiatives are a part of rule-based systems to the extent that they do not challenge the principles and norms of a multilateral trading system.

RTAs are discriminatory in nature; they are generally exclusive, asymmetric, and do not effectively address many challenges beyond their regional confines. They can also lead toward separate trading blocs with their own regulatory spheres.

3. Unilateral Measures and Countermeasures

Unilateral trade measures are typical reciprocity laws designed to deter trading partners that are deemed to violate the rights of the implementing member. The reinvigoration of Section 301 of the US Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act that addresses unjustified, unreasonable, and discriminatory practices, as well as Section 232 which imposes measures for the sake of “national security” demonstrate the resurgence of unilateralism. They provoke retaliatory countermeasures that are costly and disruptive to trade patterns and global supply chains. The sanctions could lead to breaches of WTO law in the name of enforcing its improvement, which could further erode the rule-based trading system.

4. Plurilateral Agreements

Achieving consensus in the WTO is difficult given its members’ economic diversity. Many studies have proposed alternative negotiating modes to adopt rules for new disciplines (Warwick Commission 2007; Elsig 2016).[4] The goal should be helping members who are willing to promote a forward agenda through reducing the possibility for others to block negotiations merely to stop the process. In this context, several plurilateral agreements were negotiated.

Despite limitations, plurilateral negotiations can bring progress in many policy areas, if standalone multilateral agreements cannot be finalized. They can be useful in diverse areas such as domestic regulation of services, e-commerce, investment facilitation, SMEs, digital trade, subsidies, environmental goods, regulatory cooperation, etc. Plurilaterals must allow non-members to join after the original creation without facing harder conditions (Gallaher and Stoler 2019, 389). They should also be multilateralized by keeping them within the WTO scope.

Along with these options, it is essential to maintain multilateral dialogue open. The G20 has a pivotal role in tackling the challenges to multilateralism and in preserving the sustainability and centricity of a functioning and effective WTO system.

Key recommendations

With the above comments in mind, based on reform proposals by stakeholders and considering the changing global circumstances that the WTO faces, the following recommendations are proposed:

1. The G20 should initiate a deliberative dialogue platform to help identify and resolve controversial issues

Controversial issues among key players are formidable and reforming the WTO system will not be easy. The G20 could be a platform that initiates a deliberative dialogue among its members, which would represent both advanced and developing economies. G20 members represent a critical mass of global trade in all major areas and are involved in substantial challenging issues for the WTO system. G20 members can play a collective leadership role in discussing a coherent initial approach to identify differences and priorities and to examine agreeable solutions.

The goal of the dialogue could be developing a set of ideas that could improve the conditions for discussing options. In the context of the G20, the debate should not in any case aim to replace the WTO as a forum for negotiations and rulemaking. G20 members must also assure other WTO members that the discussion would be a general, preliminary talk to help understand what is possible. The dialogue’s primary objectives should be:

- to provide a platform that can build mutual trust among stakeholders;

- to expedite the development of new rules while preserving the core principles of the rule-based system under changing global dynamics;

- to make concrete action plans for necessary reforms in order to realize the proposals stipulated in various G20 statements;

- to recall previous efforts for full implementation of decisions in previous Ministerial Conferences, and joint initiatives held in MC11.

2. The G20 can empower the Trade and Investment Working Group to improve dialogue

The G20 countries should give a clear and implementable mandate to the Trade and Investment Working Group (TIWG), which is composed of representatives from trade ministries. This is to operationalize the deliberative framework within which they ascertain major challenges to be addressed and offer a roadmap with a clear, long-term work program for actionable proposals. The TIWG can develop its own agenda for achieving the objectives (Hoekman 2016).[5]

When identifying priority issues, the TIWG should match the most viable negotiation track with each related discipline so it can be offered to the WTO’s relevant bodies. In implementing its mission, the TIWG can be chaired by the Presidency and co-chaired by member representatives.

The TIWG should establish institutional dialogue with T20 task forces. Engagement with business representatives and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provides a deeper understanding of their perspectives regarding the trading system’s functions. The G20 can be asked to provide a comprehensive report identifying challenges in the WTO system and soft approaches for solutions. The TIWG should regularly report developments and its recommendations to Trade Ministries and G20 Sherpas in order to channel their findings to the relevant WTO committees and bodies. The TIWG should consider inclusiveness by inviting non-G20 countries and least developed countries (LDCs) under accepted schemes.

The TIWG could be supported by sub-committees regarding substantial issues like industrial and agricultural subsidies, trade in services, special and differential treatment (SDT), digital trade, and dispute settlement, as well as procedural aspects such as identification of conditions for plurilaterals and other alternative methods of negotiation. A scientific consultation board can be established to study and analyze the impact of alternative approaches to substantial and procedural topics. Referring to the G20’s Osaka Declaration, best practices can be adopted in the light of RTA experiences, with a committee created to endorse the complementary roles of free trade agreements (FTAs) and mega trade agreements with the WTO agreements.

3. A progressive approach to systemic controversies must be adopted

Given its controversial aspects, a debate on “non-market economy” is a non-starter. Instead, G20 members should discuss integral parts of the debate (trade-distorting subsidies, the case of SOEs, technology transfer, etc.) first by examining their legitimacy and the need to incorporate them into the new rulebook and then by considering the viability of success under the most appropriate path for negotiations.

The members should refrain from further politicizing the development (SDT) issue. A clear understanding of how developing countries can flexibly operate and how it has affected their development needs could be the starting point. Developing countries learn only through practice that development is not sustainable unless properly supported by domestic policies. They must assess if SDT is consistent with their needs and concerns. Advanced economies, on the other hand, must consider that SDT or weaker regulatory standards used by developing countries are not the main culprits that diminish trade gains and employment. The larger concern is productivity in sectors/firms that cannot adjust to competitive dynamics like offshoring or technological changes (Akman et al. 2018).

Justification of SDT was manifest in WTO 1.0, which was designed to govern trade in goods made in one location. However, with the internationalization of supply chains, developing countries cannot benefit from protectionism, which destroys their industries and harms their development prospects (Baldwin 2014, 279). G20 members with developing country status should initiate a self-assessment regarding their status by reporting regularly about their implementation and legitimacy. The development dimension of policy dialogue must embolden capacity building for developing countries so that they make new commitments in areas that require new rules.

4. Coping with contingencies like pandemics that can distort trade is essential

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced policymakers to simultaneously deal with economic problems and a public health emergency. The G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Statement on March 30, 2020 noted that emergency trade measures must not impede the accessibility of medical products and other essential goods and services during the fight against the pandemic; they must be targeted, proportionate, transparent, and consistent with WTO rules. To deliver the objectives in the Statement, G20 members could negotiate for a Plurilateral Agreement on Rules and Procedures Applicable on Trade in Medical Products and Services. The Singapore–New Zealand declaration could provide a starting point for the Agreement. The same is true for export measures preventing flow of essential food supplies under contingencies, as raised by the G20 Extraordinary Agricultural Ministers Meeting Statement on April 21, 2020.

When the world is confronted with the COVID-19 pandemic, a functioning global trading system with the WTO at its center is more important than ever to ensure the efficient supply of critical products, coordination of global action, and support for the global trading system.

5. Consider soft mechanisms that are applicable to global trade governance

In addition to open policy dialogue and formal negotiations, new cooperation mechanisms that emerged in different domains at the multinational level can be examined by the G20 to govern trade relations. These mechanisms can address the heterogeneity of national preferences and systemic divergences in the formation of global collective action.

Soft mechanisms of global governance, such as pledge-and-review mechanisms, collaboration between independent agencies, and open partnerships involving non-state participants, have been applied in other fields such as central banks cooperation, competition policy (cooperation between national authorities with domestic mandate for collective action), and emission reduction commitments (the 2015 Paris Agreement aimed at creating soft reciprocity through a bottom-up process of voluntary mitigation pledges and review of actions). These mechanisms do not affect national sovereignty and promote transparency and monitoring of domestic behavior. One of their controversial aspects is the risk associated with private actors’ involvement in the political process. Beyond a simple consultation, the involvement of the business community in a more formal engagement process, especially in regulatory policies and mapping of supply chain costs, could help improve global governance mechanisms in many areas.

6. Assess the possibilities of achieving consensus

Agreements in the WTO must be reached on a consensus basis, making them increasingly difficult to realize as the number of major economic powers increase. The members can facilitate the decisions and rulemaking process by using a “blocking minority” rule (in voting procedures under Art. IX of WTO Agreement), wherein the consensus is only broken if countries that constitute a critical blocking mass reject the decision. In order to preserve the legitimate expectation of any dissident member, the agreement can provide agreed upon flexibilities.

Plurilateral agreements (critical mass agreements) should be seriously considered to prevent problems in achieving consensus. An influential method could be open plurilateral negotiation that is inclusive and gives non-participating developing countries the opportunity to benefit from rules and market-access. Incentives to prevent freeriding need to be examined. To ensure the primacy of the multilateral system, all plurilateral agreements must be incorporated within the WTO rather than being undertaken outside its scope.

Success criteria need to be considered for every individual area, including crossborder trade in services, e-commerce, e-services, competition policy, and industrial subsidies. Examining what should be considered “critical mass” (e.g. 90% or less in specific areas) is also important. This must be investigated for each sector, considering the delicate balance between a lower threshold and permitting a smaller number of willing parties in order to start the process and inviting participation by a larger group in order to represent universality and inclusiveness.

The TIWG could establish a sub-committee focusing on plurilaterals to examine the criteria for success, monitoring, and incorporation into the WTO system. It can also work on the principles and procedures to be followed to assist the WTO.

7. The G20 should foster dialogue for transparency, monitoring, and institutional renovations in the WTO

A number of technical or procedural reforms should be pursued to preserve and improve the functions of the WTO by ensuring transparency and monitoring. Institutional procedures at the WTO can be improved for the functioning of committees and in decision-making procedures. The G20 can play a key role in fostering dialogue on these reforms and develop a multi-year road map of WTO reform agenda.[6]

8. Reduce tensions surrounding the issue of subsidies[7] and strengthen WTO disciplines for their surveillance and implementation

Subsidies have become policy instruments that lead to market-distortions, overcapacity, and unfair competition. The G20/TIWG can establish a sub-committee comprised of senior trade and finance officials with the expertise to provide core principles and guide negotiations to reform the issue of subsidies. The principles could include assessing cross-border spillover effects as well as providing restrictions on the use of subsidies and their gradual phase-out possibilities. The committee could also study the most problematic subsidies and flaws in the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, and identify plurilateral paths forward for a broader reform agenda.

9. Trade barriers must be WTO-compatible and transparent

Despite efforts to liberalize global trade, G20 countries have been predominantly responsible for implementing trade-restrictive measures since the global economic crisis. G20 members resort to additional duties, export measures, and trade contingency measures such as safeguards and anti-dumping duties. The G20 must ensure that these measures are implemented consistently with WTO rules, and there should be a peer-review process among G20 members, through the TIWG, to identify incidents when measures are not implemented in a way that is consistent with WTO rules and are not notified appropriately by the parties.

Measures advocating national security exceptions are likely to increase under Art. XXI. An understanding on the implementation of Article XXI of GATT 1994 could be proposed to provide a clear interpretation for its scope and to prevent national security exceptions from being a new loophole in the system, though it is a highly controversial issue.

10. Address digital trade and transformation

WTO reform will be incomplete without achieving limitations on digitalization of trade. Rules need to be developed regarding the liberalization of e-commerce, e-services, and electronic payments. These rules should address issues like taxation of digital services and regulation of trade-related data flows.

11. Resolve the impasse in the DSM

The deadlock over the AB needs to be resolved immediately. Preventing the collapse of the DSM is a key issue for all WTO members. Without a DSM, the WTO loses its formal enforcement power.

The proposal that other WTO members could have the collective responsibility to administer the rules and procedures of the dispute framework to fill the vacancies by three-quarters majority (Article IX of the WTO Agreement) is innovative, but may not be politically effective (Zedillo 2019). Possible interim solutions, like having no-appeal procedures during the stalemate until the concerns of the US are addressed, could cause pressures on the system without targeted improvements (CIGI 2019).

The recent approach by the EU, along with others, for a contingency multiparty interim appeal (MPIA) arrangement under Article 25 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) is a concrete initiative to prevent blockage though it cannot permanently replace the DSM. It is an important step toward upholding the rule-based multilateral trading system. Its success, however, would depend on the willingness of other parties to participate. It cannot apply to disputes between the US and others, hence leaving many cases in limbo.

The stalemate in the DSU could be most properly resolved if the WTO’s rulemaking function is strengthened and its rules are revised and upgraded. Improved rules will diminish the burden on the AB for legal interpretations in areas that are not well defined, and keep its reports from being treated as precedents.

It is also important to note that the WTO’s revised DSM should be applicable to plurilaterals and provide more detailed and careful consideration of the particularity of these agreements.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate Ms. Anabel Gonzalez, coordinating co-chair and two anonymous external reviewers for their helpful comments and recommendations.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Akman, Sait, Shiro Armstrong, Uri Dadush, Anabel Gonzalez, Fukunari Kimura, Junji Nakagawa, Peter Radish, Akihoko Tamura, and Carlos A. Primo Braga. 2020. “World Trading System under Stress: Scenarios for the Future.” Global Policy Journal, 11, no. 3 (January): 360-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12776.

Akman, Sait, Clara Brandi, Uri Dadush, Peter Draper, Andreas Freytag, Miriam Kautz, Peter Rashish, Johannes Schwarzer, and Rob Vos. 2018. “Mitigating the Adjustment Costs of International Trade.” Paper presented at the T20 Argentina 2018 Think 20, Argentina. https://t20argentina.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Tf-7-7-1-AdjustmentCostsG20FormatMay232018-2.pdf.

Baldwin, Richard. 2014. “WTO 2.0: Governance of 21st century trade.” The Review of International Organization, 9, no. 2 (March): 261-283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-014-9186-4.

Bhagwati, Jagdish, Pravin Krishna, Arvind Panagariya. 2014. “The World Trade System: Trends and Challenges.” Paper presented at the conference at Trade and Flag: The Changing Balance of Power in the Multilateral Trade System, Bahrain, April 7-8, 2014. https://www.columbia.edu/~jb38/papers/pdf/paper1-the_world_trading_system.pdf

Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). 2019. “CGI Expert Consultation on WTO Reform: Special Report: 2018.” Waterloo, Ontario, CN: CIGI. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/WTO%20Special%20Report_0.pdf.

Elsig, Manfred. 2016. “The Functioning of the WTO: Options for Reform and Enhanced Performance.” Synthesis of the Policy Options No.9. Geneva: The E15 Initiative by ICTSD and WEF. https://e15initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/E15_no9_WTO_final_REV_x1.pdf.

Evenett, Simon J. 2020. “Tackling COVID-19 Together: The Trade Policy Dimension.” Global Trade Alert. https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/51.

Felbermayr, Gabriel. 2020. “The WTO needs a Plan B.” Global Solutions Journal, 5 (April): 71.

Gallaher, Peter. and Andrew Stoler. 2009. “Critical Mass as an Alternative Framework for Multilateral Trade Negotiations.” Global Governance, 15 no. 3: 375-392. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01503006.

Hahn, Michael. 2019. “For Whom the Bell Tolls: The WTO’s Third Decade.” in The Shifting Landscape of Global Trade Governance, edited by Manfred Elsig, Michael Hahn, and Gabriele Spilker, 121-54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108757683.006.

Hoekman, Bernard. 2016. ”Revitalizing the Global Trading System: What Could the G20 Do?” China and the World Economy, 24 no. 4 (July): 34-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12166.

Mavroidis, Petros C. and André Sapir. 2019. “China and the World Trade Organisation: Towards a Better Fit.” Bruegel Working Paper, Issue 06, June 2019, Brussels.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. “Joint Statement on Trilateral Meeting of the Trade Ministers of the United States, Japan, and the European Union.” Press release, May 31, 2019. https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2018/may/joint-statement-trilateral-meeting.

Warwick Commission. 2007. The Multilateral Trade Regime: Which Way Forward: The Report of the First Warwick Commission. United Kingdom: University of Warwick.

White House. 2019. “Memorandum on Reforming Developing-Country Status in the World Trade Organization.” Last modified July 26, 2019. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/memorandum-reforming-developing-country-status-world-trade-organization/.

Zedillo, Ernesto. 2019. “Act Now to Save the WTO.” Vox EU, December 9, 2019. https://voxeu.org/content/act-now-save-wto.

Appendix

[1] . The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), Information Technology Agreement-II, ban on agricultural export subsidies, and joint initiatives launched at MC11 are major exceptions, and can be noted as positive steps.

[2] . Mavroidis and Sapir (2019) argued that SOEs and technology transfer are two areas “to curtail the role of the state to unleash the potential for liberalization through renegotiation (multilateral ideally or plurilaterally).”

[3] . See Office of the United States Trade Representative 2018.

[4] . The Warwick Commission in its 2007 Report proposed a “critical mass approach” that can be applied by respecting the interests of the entire membership and at the same time securing the continued commitment of all parties for negotiations and rulemaking (p.36).

[5] . Hoekman, B (2016, 42) noted that “the creation of the TIWG provides a potential vehicle for G20 officials to deliberate on what G20 might focus…”

[6] . See, T20 Saudi Arabia TF1 PB2 “Improving key functions of the WTO” by A. Berger et al.

[7] . See, T20 Saudi Arabia TF1 PB3 “Industrial subsidies as a major policy response since the Global Financial Crisis” by P. Draper et al.