Basel III was a direct answer to the 2008 financial crisis. Now 10 years after the crisis, it is time to assess its timeliness and make the necessary adjustments so it becomes truly global.

In this policy brief, we first clarify the goals of macroprudential policy before highlighting the main challenges that home and host countries may run into when global financial institutions lend beyond their home countries.

We then suggest to focus on four priorities to address these vulnerabilities:

– An adaptable and flexible global Framework

– The generalization of international standards and best practices

– A stronger global data depository

– Regulatory and monitoring cooperation

Challenge

Macroprudential Policy in a Nutshell

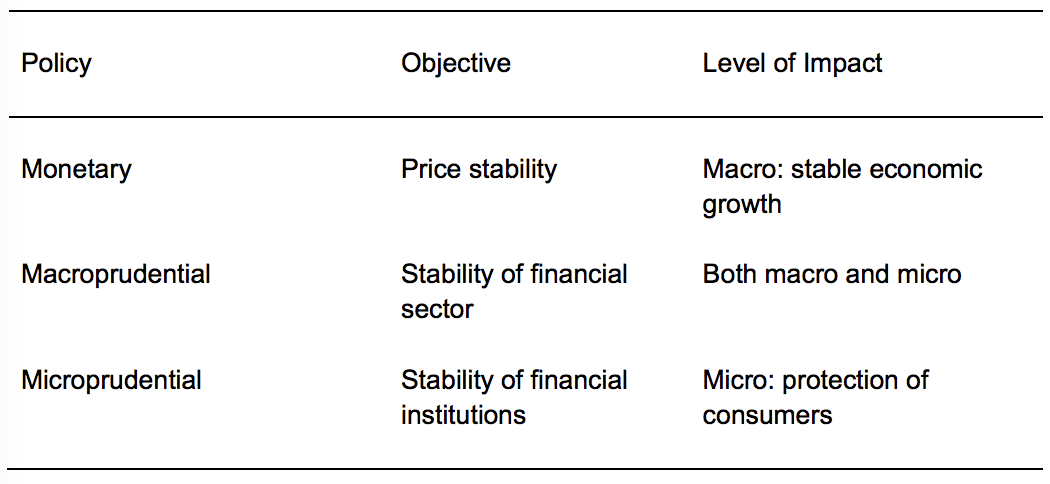

Understanding the fundamental rationales behind macroprudential policy is essential to appreciate how it complements monetary, fiscal, and structural policies. Indeed, financial regulatory policies are not enough to address systemic risk, and other policies — especially monetary and fiscal policy — have roles to play, depending on the underlying cause of the problem (1). Relying on macroprudential policy to counter aggregate shocks such as commodity price shocks or policy deficiencies such as poorly conducted microprudential and monetary policies would not be the appropriate answer.

Macroprudential supervision is concerned with the stability of entire industries and the health of the relationships within the financial sector that can significantly impact the economy. More specifically, its principal goal is to monitor systemic risk and to enhance the resilience of the financial system so it can fulfill its three main functions (to provide the core financial services of intermediation, risk management, and payments) even when under significant stress (2).

The G20 used macroprudential principles to design a coordinated policy answer to the 2007-08 crisis. Basel III has yet to be fully implemented — see FSB (2018) for a detailed assessment —, but so far the outcome is clear: banks (and insurance companies) have been pressured to reduce their complexity, leverage, and riskier lines of business to decrease the chances of another financial crisis. Nonbank financial intermediaries have stepped in to fill the vacuum, and alternative financial instruments have helped to rearrange intermediation needs across different actors. Market-making activities are subject to new transparency requirements, ensuring that more financial products will be traded through exchanges, instead of over the counter.

We are highly supportive of this framework and of the FSB work programme for 2019 (3). More specifically, we strongly agree that ending too-big-to-fail can only work if the last step is operational. That is it requires a well-identified resolution authority and an orderly resolution plan for SIFIs (banks, CCPs…) that is implementable in time of crisis (4).

Furthermore, the global political, financial and economic conditions have changed since Basel III was initially designed, and the framework should be adjusted to reflect the new sources of vulnerabilities. More specifically in this brief, we emphasize the challenges that home and host countries may run into when global financial institutions lend beyond their home countries.

We propose to focus on the following four priorities to address these issues:

– An adaptable and flexible global framework

– The generalization of international standards and best practices

– A stronger global data depository

– Regulatory and monitoring cooperation

Proposal

The quiet buildup of financial “fault lines” leading up to the 2007 crisis was due in part to financial institutions’ and regulators’ growing overconfidence in their ability to manage risks. Financial institutions were confident they had eliminated most of their risks by hedging their known idiosyncratic (individual) risks with products like credit default swaps, and diversifying exposures based on historical return relationships (e.g. real estate performance is a mostly local phenomenon so a sustained nationwide downturn is mathematically near impossible). Regulators monitored individual financial institutions in an attempt to ensure that no single body was taking outsize risks. Unfortunately, both sides ignored the build-up of risk outside of the scope of their purview.

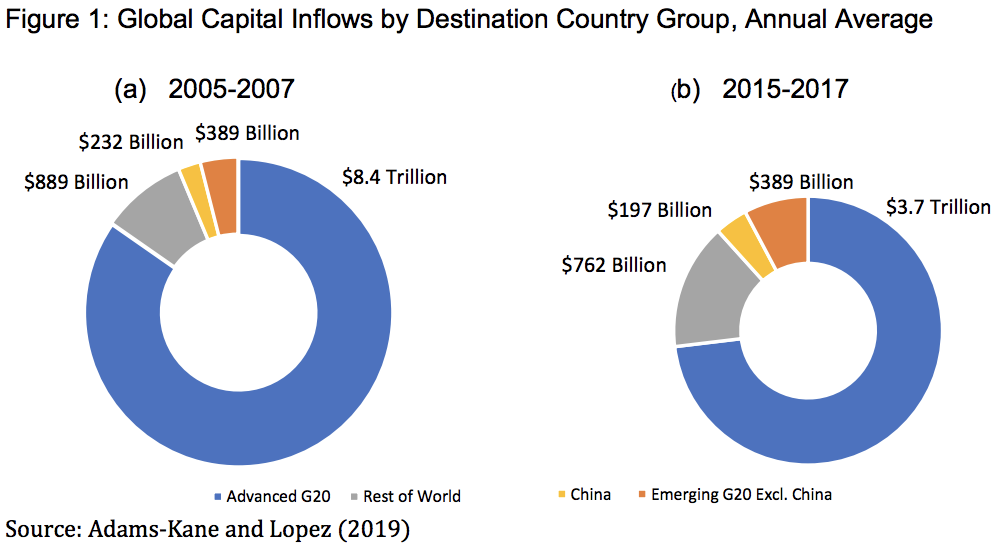

While many of the weaknesses identified during the crisis have been addressed, the risk of complacency and overconfidence remain high in our eyes. Indeed, the current framework overlooks unexpected consequences such its spillovers on smaller or less developed countries. The increase of capital inflows in the non G20-advanced countries over the past 10 years — see Figure 1 — also indicates the strengthening of the connections between countries; hence any brutal changes in these flows can become an issue beyond the less developed markets: by attracting more capital flows a country is more integrated into the global financial system, and it can affect it—directly or indirectly. Ultimately, the resilience of the domestic and international financial system depends in part on countries’ ability to adopt and to effectively implement the relevant international regulatory and supervisory policies and standards while their financial system deepens.

While for many of these countries their global importance is to come, the time to act is now: there is always a lag between the speed of change in a country’s financial system and in its regulatory oversight. This is especially true when it comes to less developed countries, due to the lack of fully develop institutions that would provide the expected information (data collection) and its analysis.

What are the risks?

Focusing on the global impact of the macroprudential policy framework, we have identified the following five sources of vulnerability that require the immediate attention of the G20. Most of them arise when large financial institutions have activities outside their home country.

Underestimating a build-up in credit risk in countries that have institutional weaknesses, such as inadequate company accounting, auditing, financial reporting, and disclosure, as well as the absence of an adequate credit bureau or register. While the local authorities may have a better understanding of local conditions, it is difficult to share that knowledge with a foreign institution or regulator effectively. Indeed, the foreign-owned institution’s risk management and measurement systems might not work well due to the poor quality of economic and financial data on borrowers, misleading the institution as well as its home country regulators.

Regulatory arbitrage increases with the greater presence of foreign-owned financial institutions, especially when it comes to lending via subsidiaries, branches, non-bank financial institutions owned by foreign banks, or direct cross-border loans. Hence, regulators in less developed countries with a large presence of foreign financial institutions tend to have difficulties in preventing the emergence of a credit boom or to bring it under control without the help of foreign regulators.

Implementing the current policy framework at the global level is still very much a work in progress. Basel III is the most recent effort in a series of attempts to enhance and expand international regulatory standards, especially for banks. Ultimately, the goal is to help countries’ financial system resilience by addressing structural weaknesses such as those in capital adequacy; liquidity positions; lending standards; risk management systems; bank governance; supervisory and reporting frameworks; and licensing, competition, and bankruptcy arrangements. The treaty was a direct response to a crisis that originated in the advanced economies. Given the large differences in the degree of financial market development between advanced and emerging economies, some of the recommendations may not be relevant.

Foreign and national regulators may have complementary jurisdiction in the presence of global financial institutions—, especially banks. In less developed countries, this may lead to a mismatch in policy priorities between foreign and national supervisors and regulators, especially when a local crisis emerges. For instance, host authorities may be concerned about local financial instability risks (such as boom-bust cycles in domestic asset prices or demand and external balance pressures resulting from rapid credit growth). They may not have the tools or authority to mitigate them because foreign institutions may be outside of local authorities’ jurisdiction. The evolution of separate institutional responsibilities in many countries has complicated this matter: the central bank is usually responsible for financial stability and macroeconomic policies, while a financial supervisory authority is primarily concerned with the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions.

Prudential supervisors’ conflicts may rise when a foreign-owned subsidiary or branch is systemically important locally and runs into problems. The incentive effects flowing from crisis resolution arrangements play a key role. During times of acute problems, the host and home supervisors may have different incentives. The primary concern of the parent institution’s home country supervisor is to prevent the subsidiary from bringing into question the solvency of the entire firm. In contrast, the host country’s main concerns are to mitigate liquidity and solvency problems at the subsidiary level and to maintain overall lending and capital inflows to the country.

Policy recommendations:

The G20 is an essential platform to discuss and design such cross-border policy framework and standards. The diversity of its members, with very different levels of economic and financial development, ensures the representation of a broad range of views. However, the 2008 financial crisis triggered the last comprehensive discussion on financial reforms—a crisis driven by financial activities in the United States and other advanced economies. Officially, 2019 is the final year for the implementation of Basel III: it is an appropriate time to assess what are the necessary changes to make this macroprudential policy framework truly global.

On the one hand, it needs to accommodate different degrees of economic and financial market development within the same system. On the other hand, financial market integration requires international coordination and cooperation to function effectively.

These are very ambitious goals. Achieving them requires that the discussions and negotiations within the G20 framework take into account all point of views, from advanced and less developed economies. We believe that these discussions should focus on the following four priorities:

1. An adaptable and flexible global framework: The global regulatory and monitoring framework needs to be made pertinent for a wide range of economies and financial systems and able to address their specific issues. Rapid advances in financial technology are making available a wide range of tools for developing and modernizing emerging countries’ financial systems even when they do not have a well-developed banking system. The existing regulatory and monitoring frameworks must adapt to reflect such developments.

2. The generalization of international standards and best practices: Reliable and standardized sharing of information and data across the globe is key to effective risk monitoring and management. However, many emerging countries need technical support from international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank to adopt and implement the (relevant) standards and to supply the necessary training to develop the required in-house expertise and monitoring infrastructures.

3. A stronger global data depository: Directly linked to the previous point, it is essential to develop the relevant reporting, supervisory and regulatory infrastructures that will enable the effective and safe sharing of relevant data and analysis.

4. Regulatory and monitoring cooperation: When an internationally owned financial firm has a local branch or subsidiary that is locally systemic, the local regulators may require help from home regulators for timely and effective action in advance of a crisis. This coordination requires agreement about goals and priorities among advanced and emerging market regulators who may face different incentives. Ultimately, the tools and mechanisms available for coordination need to be explained clearly and mutually agreed upon well before the outbreak of any crisis. While effective coordination to pre-empt a crisis is a very ambitious goal, it starts with discussions and negotiations within the G20-framework that will take into account all point of views, among advanced and emerging market policymakers.

References

• Adams-Kane Jonathon and Claude Lopez (2019), Global Opportunity Index 2018: Emerging G20 Countries and Capital Flow Reversal, Milken Institute Report.

• Bruni, Franco and Claude Lopez (2019), Monetary Policy and Financial System Resilience, T20 recommendation.

• FSB (2018), Implementation and Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms, Fourth Annual Report, FSB report.

• FSB (2019), FSB work programme for 2019, FSB publication.

• IMF-FSB-BIS (2016), Element of Effective Macroprudential Policy, IMF-FSB-BIS report.

• Lopez, Claude, Jonathon Adams-Kane, Elham Saeidinezhad and Jakob Wilhelmus (2018), Macroprudential Policy and Financial Stability: Where Do We Stand?, Milken Institute Report.

• Lopez, Claude and Elham Saeidinezhad (2017), Central Counterparties Help, But Do Not Assure Financial Stability, Milken Institute Report.