This document outlines the position of a group of research and non-governmental organizations on care needs and care policies in the G20 countries. It provides a summary of why addressing care needs is fundamental for women’s economic empowerment and labour market participation and frames these policies in terms of protecting the right to care and be cared for. We call for more effort to recognize, reduce, redistribute and represent unpaid care work and to protect the rights of paid care workers. We provide a number of examples of successful policy and programme initiatives for G20 countries to consider expanding in their own domestic policy agenda as well as their development assistance to further women’s economic empowerment globally.

Challenge

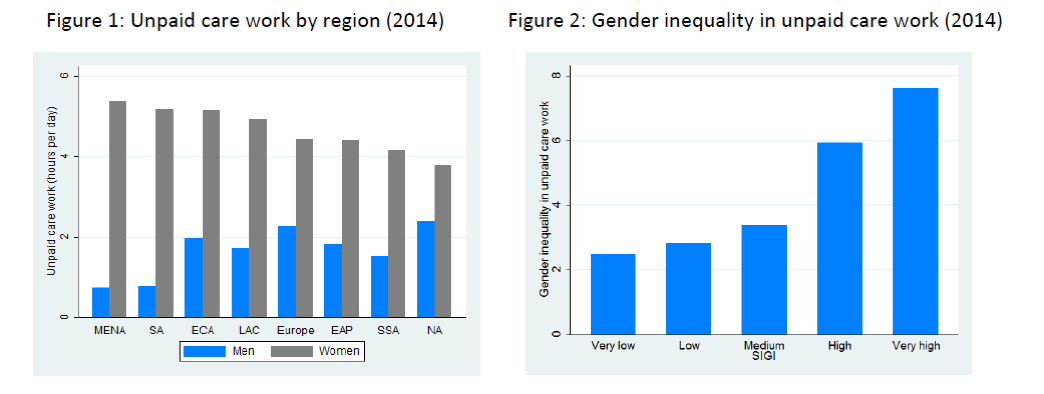

Worldwide, the responsibility for unpaid care work (UCW) falls disproportionally on women and girls, leaving them less time for education, leisure, self-care, political participation, paid work and other economic activities. The social construction of gender roles and responsibilities shapes and reinforces the gender division of labour where men are over-represented in paid work and women in unpaid care work. Yet while these patterns are changing and more women are entering paid work, the bulk of unpaid care work continues to be undertaken by women and girls (Figure 1), leading to longer work days and more time poverty.

Much of unpaid care work is devoted to caring for household members and household provisioning such as cooking, cleaning, washing, mending and making clothes. Gender gaps in unpaid care work tend to be greater in those countries with poorer infrastructure and less well-developed education and social protection systems (Figure 1). They are also higher in those countries with more discriminatory social institutions that place normative and legal restrictions on women’s economic and social rights and mobility (Figure 2). This said, however, it should be noted that in all G20 countries, women spend more time on UCW than men.

Note: The Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) database is a cross-country measure of discrimination against women in social institutions (formal and informal laws, social norms, and practices) across 160 countries. Gender inequality in unpaid work is defined as the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care activities by region and income group. https://www.genderindex.org/

Source: Ferrant,G., L. M. Pesando and K. Nowacka (2014) “Unpaid Care Work: the Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps and Labor Outcomes, OECD, Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/Unpaid_care_work.pdf

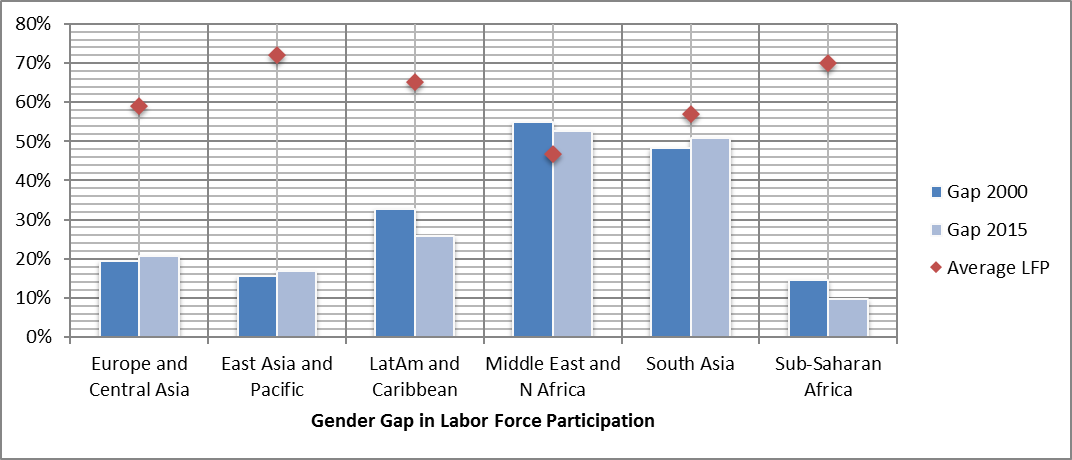

Care work takes up a significant amount of women’s time in many countries, and particularly in contexts where infrastructure is poor and publicly provided services are limited or absent (Counting Women’s Work 2018; ICRW 2005; ADB 2015; Oxfam 2018; OECD 2016a,b). The burden of care work is more acute in rural settings, in contexts with growing numbers of single-parent households headed by women, high-fertility countries and in ageing societies. Women’s responsibilities for care work limit their engagement in labour market activities, exacerbate gender gaps in labour force participation (see Figure 3), reduce their productivity, increase labour market segmentation and lead them to concentrate in low-paid, more insecure, part-time, informal and home-based work as a means of reconciling unpaid care work and paid employment. The disproportionate representation of women in certain sectors and occupations contributes to gender wage gaps that undervalue women’s labour and inflate the numbers of the working poor (ILO, 2016; Labour Participation T20 Policy Brief; UN Women, 2015). Globally, the gender pay gap is estimated to be 20% which means that on average women earn 80% of what men earn (ILO, 2016). The gender pay gap rises for workers with childcare responsibilities (ILO, 2016; Grimshaw and Rubery, 2015; Elming, Joyce and Costa Dias 2016; Flynn and Harris 2015). In this scenario, where carers are disproportionately exposed to unemployment, informality and poverty, we consider it essential to move towards universal access to care as a right.

Figure 3. Gender gap in labour force participation

Notes: Gap in labour force participation rates between the percentage of men and women over the age of 15 who are working. Average LFP refers to average labour force participation for men and women over 15 years of age. Data are from the World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Source: Gammage et al (2017). “Evidence and Guidance on Women’s Wage Employment,” report to USAID. https://www.marketlinks.org/library/evidence-and-guidance-womens-wage-employment

Care Crisis & Implications

Across the world we confront persistent care deficits where care services are either not available, not affordable or are inadequate and insufficient and where women disproportionately bear the responsibilities for caring for others, devoting a greater proportion of their time to caring (Alfers, 2016). Recent research by the Overseas Development Institute underscores that we are indeed facing a global care crisis where care needs outstrip the supply of care services (Samman, Presler-Marshall, & Jones, 2016). These authors found that:

- Across 53 developing countries, some 35.5 million children under five were without adult supervision for at least an hour in a given week.

- Across 66 countries covering two-thirds of the world’s people, women take on an extra ten or more weeks per year of unpaid care work.

- On average, women spend 45 minutes more than men daily on paid and unpaid work – and over 2 hours more in the most unequal countries. The difference is the equivalent of 5.7 weeks of more work per year.

- Across 37 countries covering 20% of the global population, women typically undertake 75% of childcare responsibilities – with a range of 63% (Sweden) to 93% (Ireland).

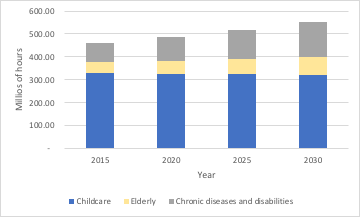

The current social organization of care is largely by default and not by design. Rising female labour market participation in most of the world has not occurred with the equivalent redistribution of unpaid care work and as a result time burdens have risen and care provision has been compromised. The market and the state do not offer sufficient services and care provision continues to be resolved informally in many contexts (Samman et al 2016; Alfers 2016). This imbalance between care supply and demand will only increase as more countries advance in their demographic transition and elder care needs and care requirements for the sick and those with disabilities rise (Help Age 2018[1]; Scheil Adlung 2015). One example of this challenge is in Mexico, where it is projected that between 2015 and 2030, the demand for direct care will increase due to the combined effect of population aging and an increase in the prevalence of chronic diseases and disabilities, as people live longer and disease burdens and disability increases. This rise in care needs will happen despite the declining need for child care (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Projected Direct Care Needs in Hours, Mexico

Notes: Projections assume that unpaid care time received by individuals will remain constant.

Source: Rivero, E; E. Troncoso and E. Max. (2018) “Informe prospective de cuidados,” report to UN Women.

The European Quality of Life Survey underscores that multiple barriers exist reducing access to care services in G20 countries and beyond. These barriers include span affordability (the services that are available in the market are expensive and unaffordable for many), availability (there are insufficient services on offer), accessibility (physical distance or inappropriate opening hours limit use) and quality concerns (Eurofound, 2012). Addressing these barriers will be critical if we are to reduce the burden of unpaid care and guarantee the right to care and be cared for and adhere to commitments enshrined in the 2014 Brisbane commitment to reduce the gender gap in labor force participation (University of Toronto 2014).

[1] As societies age, people live longer with chronic ailments and a greater proportion of their lives is spent with mobility or other physical and mental challenges that limit their autonomy and independence.

Proposal

Care is essential for the young, the sick and the elderly. At some point in our lives we all need care and benefit from the care of others. This policy brief underscores that we all have a right to care and to be cared for (United Nations, 1948; WHO, 2017; RELAF/UNICEF, 2015).[1] The goal is to develop health care, education and social protection systems that support caring without penalty, either for those who receive care or for those who may choose to enter the labour market. In practice, this means that those who choose to care can do so and those who choose to work can be sure that their loved ones and family members are being cared for adequately.

Social protection systems can be essential platforms for integrating care services and meeting care needs, establishing the right to care and be cared for. Fully funded social protection systems require a commitment to increased public spending financed by progressive tax systems (Action Aid 2017). This is central to Uruguay’s Care system (see Box 1) which recognizes care as fundamental human right.

Box 1. Uruguay’s National Care System

| Uruguay’s Integrated National Care System (SNIC) was established in 2015 following an extensive process of alliance-building and negotiation. Founded on a principle of co-responsibility between the state, community, market and families, the SNIC aims change the sexual division of labour within households and ensure the social (re)valuation of paid care work in the market sphere. It notably mandates the provision of a range of public care services – including early years childcare, elder care, the regulation of private suppliers, improvements in quality standards, and training for caregivers. The SNIC is a valuable example of progress on a national-level care agenda, resulting from a ‘virtuous cycle of data, policy and advocacy’. Key ingredients in the recipe for success included: ● Fiscal space – Progressive tax reforms starting in 2006 raised addition revenue, directed towards social protection, health and education. ● The right to care – Care was firmly established as a human right for both care providers and receivers across Latin America during the 11th Regional Conference on Women in Latin America, creating an obligation for the state to act. ● Data and evidence – Time-use surveys, initiated by academics and subsequently carried out by the National Statistical Office, quantified women’s and men’s unequal role in unpaid care and domestic work and were used to raise consciousness about the need to address care deficits. ● Feminist alliances – Women’s and labour movement activists, women politicians and feminist academics established the Gender and Family Network. They used the time-use survey findings to put care on the public policy agenda and engaged in strategic advocacy until the SNIC’s adoption in 2015. ● Political will – Gender and Family Network engagement with the government and political parties raised care up the political agenda, and in 2009 the ruling Frente Amplio included the National Care System in its electoral campaign programme for 2010–2015. ● A strong institutional mandate – In 2010, a governmental working group was established to design a new care system, creating a sense of ownership among state institutional actors. Following this, framework legislation for the SNIC was formally proposed in 2012. ● National debate – 2011 saw a high-visibility national debate on care provision take place, attracting broad-based participation from politicians, technical experts, labour unions and women’s rights organisations, among others, and galvanising public support for the SNIC. The care system addresses care needs for the young, elderly, disabled and sick and embeds the right to care in social protection systems and public provision. Uruguay provides early years child care provision; the care of disabled, the dependent and the old; and the need for support for care-givers. Key services include a cash-for-care system for home-based services, day centres and residential and nursing homes, and regulations regarding carers’ work. The November 2013 Law 19.161 introduced new entitlements, including the extension of paid parental leave when children are born, six months leave entitlement for child care, which can be taken by either parent from 2016 onwards, and new forms of financial support for parents in low income or families with young children that may not have public day-care centres and need to use privately provided services. The government also committed to the provision of 28,000 free preschool places by 2018-2019. New programmes for social assistance and services for the elderly were introduced in 2016, including 80 hours of care per month for those assessed as being in need. In addition, care homes were established to provide comprehensive care during the day and/or night for the elderly in situations of mild to moderate dependence residing in their homes, and to provide relief to the caregiving family. Part of these commitments also included the expansion of training programs for paid caregivers and the professionalization of care services. |

Source: Adapted from J. Grugel (2016) “Care provision and financing and policies to reduce and redistribute care work: Preliminary observations from Bolivia and Uruguay,” UNICEF, https://www.unicef-irc.org/files/documents/d-3922-Jean%20Grugel_Care%20abd%20children%20roundtable.pdf

Recognizing the rights to care and be cared for also includes providing critical support to those who care including health care, training, financial support and time off from caring. The UK’s Model of Care for Carers provides an important example of a set of principles that can guide how to recognize carers needs and care for carers (see Box 2). Ensuring that both paid and unpaid carers are supported and able to care in dignified conditions will be essential if we are to resolve the care crisis. Unpaid carers are frequently forgotten as their work is considered a labour of love that is offered up freely and even “naturalized” as the role that mothers, wives and spouses play.

Box 2. Ensuring Care for Carers in the UK and Australia

| The Model of Care for Carers was developed to assist social services identify gaps or areas of weakness in the assistance and support provided to unpaid carers caring for the sick and the elderly in the UK – often family members of those receiving the care – and has been adapted to provide similar support to carers in Australia. The Carers Compass identifies 8 key concerns that unpaid carers have identified as being important to them. This includes questions about information about caring and how to care, recognition of their own health needs and wellbeing, the right to a life of their own and quality services for the carer as well as the person being cared for. It also collects information about time off from caring, emotional support, training and support to care, financial security and a voice in care needs and policies. It has been used as an audit and performance management tool for National Health Services and local Authority commissions to improve support to carers in the United Kingdom and Australia. |

Source: Adapted from NSW (2007) Model of Care for Carers: Carers’ Compass and Checklist https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/Carer_Support_Program/Model_of_Care_for_Carers.asp and the WHO (2018) Women on the Move, Migration, Care Work and Health, https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/women-on-the-move/en/

National statistics are also important to recognize the volume and value of unpaid care work and its contribution to national economies. Governments must implement surveys and other instruments to measure these activities and identify the effectiveness of social programs and policies. Mexico has implemented time use surveys to help identify the value of unpaid care work on its GDP (see Box 3).

Box 3. Survey of Time Use and Valuation of Unpaid Domestic Work in Mexico

| Mexico is the first country in Latin America that calculates the value and volume of Unpaid Household Work. The National Survey on Use of Time (ENUT) is the product of inter-institutional work carried out by the National Institute of Women (INMUJERES) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). The objectives were to provide statistical information for the measurement of paid and unpaid work, and to make visible the importance of domestic production and its contribution to the economy and, in general; the way men and women use their time in urban and rural areas. Five time use surveys have been conducted: 1996 (ENTAUT), 1998, 2002, 2009 and 2014. Until 2002, the ENUT surveys were carried out as a module of the National Household Survey of Income and Expenditures (ENIGH), in in 2009 and 2014 the ENUT was then carried out as a stand-alone survey. Moreover, since 2011, INEGI has a Satellite Account of Unpaid Household Work (CSTNRHM), that provides information on the economic value of unpaid work that women and men contribute to meeting household care needs. This valuation demonstrates the importance of unpaid care work in consumption and wellbeing. The results have been used to shape key indicators for the policy processes, such as the proportion of GDP made up of the economic value of unpaid care work provided by households inscribed in the National Program for equal Opportunity and non-Discrimination against women 2013-2018, which aims to achieve substantive equality between women and men through public policies focused on reducing existing inequality gaps. During 2015, the economic value of unpaid domestic and care work reached a level equivalent to 4.4 billion pesos, which represented 24.2% of the country’s GDP; of this, women contributed 18 points and men 6.2 points. The value generated by unpaid domestic work and household care as a proportion of the country’s GDP in 2015 was higher than that achieved by some other economic activities including manufacturing, trade and real estate services and the rental of goods. |

Source: https://www.inegi.org.mx/

Importantly, women are not a homogenous group, and the burden of care is experienced differently among women. Care is often provided through ‘local’ or ‘global care chains’, in which those better off financially can often afford to purchase care services, thereby freeing up their time for paid work or other activities, while those providing services are often lower-income, or migrant women who do not have the same opportunity or choice about how they redistribute their own care work and responsibilities (Ehrenreich and Hochschild 2003; Parreñas 2012).

Ensuring that paid care workers have a right to decent work and social protection is a fundamental step in resolving the care crisis that protects the terms and conditions of employment for paid carers. In many countries facing growing care deficits, paid care work is often undertaken by informal workers without social protection and full labour rights (WHO 2018). Ensuring that paid care work is formal, regulated and of high quality will be essential if the redistribution of care responsibilities is going to take place through the state and in the market.

The world of work is changing, however, and the challenges of the gig economy and technological advancement are also likely to affect care provision and quality and the terms and conditions of work in care services (see Box 4).

Box 4: The Future of Work and Care

| Technologies are expected to transform the future of work, displacing many existing jobs and ways of working. Yet care work involves a number of skills and capacities that are likely to be the least susceptible to the impact of automation and the rising need for care indicates that care work may be expected to be an important source of employment in the future of work. The growth in care needs notwithstanding, women are likely to face greater and differentiated challenges in the future of work. Gender inequities are being reproduced and magnified in the digital world. In many emerging economies, women lag behind in terms of mobile and internet access – in India, for example, less than 30% of women have access to the internet and only 14% of women in rural India own a mobile phone (UNICEF 2017; Rowntree, 2018). Low levels of education and skilling alongside disproportionate care responsibilities reinforced by socio-cultural norms restrict women access to economic opportunities; this trend is likely to be further reproduced in the future of work. Recent studies suggest that men stand to gain one job for every three jobs lost to technology advances, while women are expected to gain one job for every five or more jobs lost. The platform economy has the potential to enable flexible work, yet, it may also reproduce and even exacerbate the current gendered division of labour. What will this mean for women and unpaid care work? One future scenario could be that as the care economy grows and its contribution to national income increases, the unpaid care work of women is increasingly recognized and redistributed. A more enabling and supportive environment for care is created – from support for carers to community care services. This could enable women to access new opportunities for economic participation and empowerment – within the care economy, their experience as carers would make them a highly valued part of the new work force, with equal pay to men, and opportunities for training and career progression. The other alternative is that as the care economy grows, and leverages new technological solutions, barriers to entry into these newly technologized jobs and sectors may increase for women. Already, much R&D is being directed towards creating robotic assistants for hospitals and homes. In this scenario, many women are likely to be displaced from their existing paid-care jobs, and the new jobs that are created within a care economy are more likely to be dominated by men, particularly if this change is technology-driven. Studies already show that gender biases restrict women’s entry into science and technology related industries, which tend to be associated with male capabilities (Tejani and Milberg, 2010). While women’s unpaid care responsibilities are likely to decrease, opportunities for decent work in other sectors will simultaneously be shrinking as well (Balakrishnan, R. L. McGowan and C. Waters, 2017). Moreover, only middle-high income households will be able to access such care-technologies, and the burden of care work on women in poor households will remain as high as before. Scenario one is undoubtedly where we want to be – but will require proactive government interventions in public infrastructure and services, education and skilling and the deliberative use of policy to steer these technological trajectories. Scenario two is much more likely if the care economy in the future of work is left to market forces alone. |

Policy Recommendations for Meeting Care Needs in the G20 and Through Development Assistance

The UN High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment identified some key principles for addressing care deficits through policies and programmes (United Nations, 2017). These embrace the recognition, reduction and redistribution of unpaid care (“3 Rs”) and added a fourth “R” for representation:

- Recognition of unpaid care work means that the work performed, which is primarily undertaken by women in the household, is both “seen” and valued economically. It also means that it is recognized as being “work.” Recognition can take several forms, including provision of compensation for the work, recognizing it when determining other benefits, such as pension payments, or measuring unpaid care work in national statistics (Budlender & Moussié, 2013).

- Reduction of unpaid care work means that the burden of caring is reduced for carers and for society more generally. This can happen when the service is provided in a different way. For example, women’s childcare responsibility could be reduced if governments provided accessible and affordable child care services. Similarly, unpaid care work would be reduced if key services were provided closer to where people live and work so that less time is spent accessing healthcare and education (Budlender & Moussié, 2013).

- Redistribution of unpaid care work means that the overall amount of unpaid care work remains the same, but it is more fairly shared among different people, the market and the state. One example of this is where male household members take on a greater share of housework and childcare. Another example is where governments provide after school care or elder care (Budlender & Moussié, 2013; Esquivel, 2008; UN Women, 2016).

- Representation of paid and unpaid carers within the policy environment and the world of work is essential. This means supporting collectives and unions and groups of organized carers to project their concerns about paid and unpaid care work into the policy discussion and in negotiations about the terms and conditions of employment.

Some examples of concrete policies that foster the 4 Rs include:

- Recognition:

- Conduct time use surveys for men and women. These should be conducted regularly and used to monitor the impact of programs and policies.

- Incorporate unpaid care in the system of national accounts and GDP estimations.

- Account for the time devoted to care in pension schemes, unemployment benefits and other contributory benefit schemes, crediting carers with time worked performing caring activities.

- Account for the time devoted to care within marriage, dividing the contributions made to pension schemes between spouses when couples divorce and or a spouse dies.

- Reduction:

- Services:

- Guarantee universal and easy access to high quality early and elder care services (these should be open beyond the typical hours of work to facilitate their use by working carers).

- Invest in the development of quality public care services.

- Services:

- Expand hours of formal education and before and after-school programs so that children can be cared for in schools accommodating their parents’ hours of work.

- Ensure access to care facilities for the dependent population (those with disabilities, the sick and the elderly).

- Provide support to carers including training, financial assistance, connecting them with carer networks and other sources of support to break isolation and provide time off from caring.

- Recognize the skills of paid carers and develop skilling pathways that offer courses and credentials that support a transition from informal to formal work and foster higher quality caring and decent work in the care sector.

- Reinforce preventive health services that lessen the burden of disease and disability in ageing societies.

- Money:

- Where care needs are met in the market, provide cash and non-cash transfers, tax credits and vouchers for families to access high quality and regulated care services.

- Infrastructure:

- Ensure households and workers have access to infrastructure and transport to reduce the time burdens providing care, accessing care services and engaging in the labour market.

- Commit to supporting overseas development investments in infrastructure, energy and technology that reduce women’s time burdens.

- Redistribution:

- Time:

- Expand paid maternity, paternity and carer leave and workplace flexibility schemes.

- Introduce incentives within family leaves schemes for men to use these leave schemes, such as non-transferrable ‘use it or lose it’ entitlements for men.

- Time:

- Engage men to actively change gender norms that foster more equal caring roles and responsibilities.

- Incorporate gender and reproductive rights into the education programs for children and youth to deconstruct gender stereotypes.

- Engage men to be more involved in careers related to early childhood care and education.

- Representation:

- Support collectives of organized carers and care workers to enable them to engage with policy processes and negotiate improvements in the terms and conditions of their employment.

- Ratify Conventions 156 on workers with family responsibilities[2] and 189[3] on decent work for domestic workers.

Appendix

Care and Fiscal Space

Expanding care service provision and ensuring the right to care and be cared for should be seen as an investment. Indeed, making “investments” in social care infrastructure can be essential for achieving greater gender equality and higher job growth. This is particularly true when these investments expand human capital development, reduce poverty and inequality, increase employment for both men and women, stimulate tax revenue generation and, as a result, increase fiscal space (Seguino 2013). A recent study by Ilkkaracan et al. (2015) in Turkey explored the employment opportunities that could be created by increasing expenditures on early childhood care centres and preschools in comparison to physical infrastructure and public housing, modelling the direct and indirect employment that would be generated. The authors found that investments in physical infrastructure would generate a total of 290,000 new jobs in construction and other sectors, while an equivalent injection into early childhood education would generate 719,000 new jobs in childcare and other sectors (2.5 times as many jobs). In addition to creating more jobs in total and more jobs for women and the unemployed, the authors determined that an expansion in childcare services would create more decent jobs than a construction boom. Of the new jobs that would be generated in care services, 85 percent were estimated to come with social security benefits, versus 30.2 percent in the case of construction-generated new jobs.[1]

The ITUC (2016) undertook a similar study for seven OECD countries, Australia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK and US. The report estimates the employment impact of increased public investment in the construction and care sector. The analysis shows that investing in either the construction or care sector would generate substantial increases in employment. The authors find that, “If 2% of GDP was invested in the care industry, and there was sufficient spare capacity for that increased investment to be met without transforming the industry or the supply of labour to other industries, increases in overall employment ranging from 2.4% to 6.1% would be generated depending on the country. This would mean that nearly 13 million new jobs would be created in the US, 3.5 million in Japan, nearly 2 million in Germany, 1.5 million in the UK, 1 million in Italy, 600,000 in Australia and nearly 120,000 in Denmark.“ The result is that women’s employment rates also rise 3.3 to 8.2 percentage points (and by 1.4 to 4.0 percentage points for men) and the gender gap in employment rates would be reduced (by between half in the US and 10% in Japan and Italy. A similar level of investment in the construction industries would also generate new jobs, but approximately only half as many and investment in this sector was forecast to increase rather than decrease the gender gap in employment.

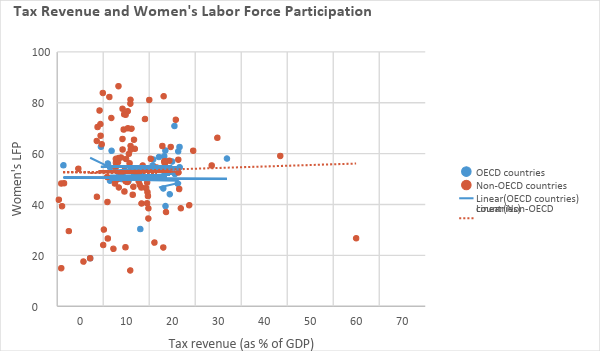

As women’s labour force participation rises, tax revenue tends to increase [see Figure 5], chiefly in those countries where employment is mostly formal. Yet increased women’s labour force participation can come at the cost of raising women’s time burdens, particularly where little investment is made in recognizing, reducing and redistributing unpaid care work and socializing the cost of care through expenditures on health, education and social protection.

Malta chose to do this by supporting the Free Childcare Scheme. The Free Childcare Scheme was launched in April 2014. The Government of Malta provides free childcare services to parents/guardians who work or who are pursuing their education. The childcare service is offered through the Registered Childcare Centres. The concept behind the scheme is to create ideal conditions for an enhanced work-family life balance, and stimulate an increased participation of women in the workforce: an important pillar for economic growth and sustainability.

Since the introduction of the scheme, over 12,000 children aged between 0 to 3 years have benefitted from free care at any particular month. As a result, the number of childcare centres which are currently providing their services as part of the Free Childcare Scheme has risen from 69 in April 2014 to 112 by the end of 2017; 88 per cent of which are privately owned.

Throughout 2017, approximately 5,940 children made use of the Free Childcare Scheme in any particular month, out of which over 3,000 were new applicants. The Free Childcare Scheme office received a total of 3,323 new applications, processed a total of 21,369 change requests, and issued payments to centres amounting to a total of €15.6 million.

In order to guarantee the quality of the service being offered, the Quality Control Unit was set up in order to conduct rigorous monitoring checks. These checks included a series of unannounced site visits covering all the childcare centres which were completed throughout Q3 and Q4 of 2017. A cross-matching exercise was also conducted against Jobsplus records to verify the employment status of parents with active applications. In cases where discrepancies were noted, emails to the respective parents’ childcare centres were sent out in order for them to regularise their situation.

The Free Childcare Scheme builds both social and economic infrastructure in Malta. With the number of mothers in the labour market steadily increasing, this leads to higher state contributions and reduced dependency on state welfare. The Scheme also has a positive effect on increased investment in human capital, and helps prevent the transmission of inequalities and ensure more gender-balanced labour markets.

As these examples demonstrate, making resources available for social programs requires reframing these expenditures as investments, precisely because by stimulating economy-wide improvements in living standards, this type of spending yields a stream of income in the future. Yet all too often, we are told there are insufficient resources available for such investments. This is simply not true. Not only do such investments generate fiscal space, and garner more taxes as a result of their positive impact on growth and employment, but more fiscal space exists than otherwise expected. A recent article by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), UNICEF and UN Women concludes that we have many more options to expand fiscal space for social spending by reducing tax evasion and under-reporting, reprioritizing public expenditures away from military spending and reducing corruption and illicit financial flows. This article reports that the global cost of corruption is estimated to be more than 5 per cent of global GDP (US$ 2.6 trillion). The African Union estimates that 25 per cent of African states’ GDP, amounting to US$148 billion, is lost to corruption every year. Surely, redoubling efforts to fight corruption are indispensable when there is such a pressing need to fund social protection, health and education – all positively associated with gender equality. Similarly, the 1997 Asian financial crisis in Thailand prompted the government to respond to civil society calls to address neglected social policies by reorienting spending away from national defence (a reduction of about 10% from the 1970s to the 2000s) and towards the creation of a Universal Health Care Scheme (at the time, one third of the population had no health coverage), People’s Bank and other measures to stimulate spending nationally and improve financial and social conditions.

Figure 5. Tax Revenue and Women’s Labour Force Participation

[1] This estimate reflects the levels of informality in construction and the seasonal nature of these jobs.

[1] Key relevant rights frameworks include Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Convention on the Rights of the Child and the InterAmerican Convention on human rights (includes the right of the elderly to care) and the outcome document of the 11th Regional Conference on Women in Latin America.

[2] See Convention 156. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C156

[3] See Convention 189. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C189

References

- Action Aid. (2017). “Women as “underutilized assets”: A critical review of IMF advice on female labour force participation and fiscal consolidation,” London: Action Aid. Retrieved from https://www.actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/actionaid_2017_-_women_as_underutilized_

- Asian Development Bank. (2015). “Balancing the Burden? Desk Review of Women’s Time Poverty and Infrastructure in Asia and the Pacific,” Manilla, Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/publications/balancing-burden-womens-time-poverty-and-infrastructure

- Alfers, L. (2016). “Our Children Do Not Get the Care they Deserve,” WIEGO Child Care Initiative Research Report. Retrieved from https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Alfers-Child-Care-Initiative-Full-Report.pdf

- Balakrishnan, R. L. McGowan and Waters, C. (2017). “Transforming Women’s Work, Policies for an inclusive Economic Agenda,” Rutgers, Solidarity Center, AFLCIO. Retrieved from https://www.solidaritycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Gender_Report.Transforming-Women-Work.3.16.pdf

- Budlender, D., & Moussié, R. (2013). “Making care visible: Women’s unpaid care work in Nepal, Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya,” Action Aid. Retrieved from https://www.actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/making_care_visible.pdf

Counting Women’s Work. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.countingwomenswork.org - Duran-Valverde, F.; Pacheco, J.F. (2012). “Fiscal space and the extension of social protection: Lessons from developing countries,” Extension of Social Security (ESS) Paper No. 33 (Geneva, International Labour Organization).

- Elming, W., Joyce, R., and M. Costa Dias (2016). “The gender wage gap,” Institute of Fiscal Studies, UK. Retrieved from https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/8428

- Ehrenreich, B. and Russell Hochschild, A. (2003). Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy. London: Granta Books.

- Eurofound. (2012). “Third European Quality of Life Survey – Quality of life in Europe: Impacts of the crisis,” Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Retrieved from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1264en_0.pdf

- Esquivel, V. (2008). “A “macro” view on equal sharing of responsibilities between women and men,” Division for the Advancement of Women, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations, New York. Obtenido de https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/equalsharing/

- Ferrant, G., L. M. Pesando and K. Nowacka. (2014). “Unpaid Care Work: the Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps and Labor Outcomes, OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/Unpaid_care_work.pdf

- Flynn, S. & Harris, M. (2015). Mothers in the New Zealand workforce. Retrieved from www.stats.govt.nz

- Gammage, S., A. Kes, L. Winograd, N. Sultana and S. Bourgault. (2017). “Evidence and Guidance on Women’s Wage Employment,” report to USAID. Retrieved from https://www.marketlinks.org/library/evidence-and-guidance-womens-wage-employment

- Grimshaw, D, & Rubery, J. (2015). The motherhood pay gap: a review of the issues, theory and international evidence. (PDF, 82p) International Labour Office, Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 57. Retrieved from https://ilo.org.

- Grugel, J. (2016). “Care provision and financing and policies to reduce and redistribute care

work: Preliminary observations from Bolivia and Uruguay,” UNICEF, Retrieved from https://www.unicef-irc.org/files/documents/d-3922-Jean%20Grugel_Care%20abd%20children%20roundtable.pdf - Help Age. (2018). “Aging in the 21st Century,” Retrieved from https://www.helpage.org/resources/ageing-in-the-21st-century-a-celebration-and-a-challenge/

- ICRW. (2005). “Infrastructure Shortfalls Cost Poor Women Time and Opportunity,” Retrieved from https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Infrastructure-Shortfalls-Cost-Poor-Women-Time-and-Opportunity-Toward-Achieving-the-Third-Millennium-Development-Goal-to-Promote-Gender-Equality-and-Empower-Women.pdf

- Ilkkaracan, I., Kim, K., & Kaya, K. (2015). The impact of public investment in social care services on employment, gender equality, and poverty: The Turkish case. Istanbul Technical University, Women’s Studies Center in Science, Engineering and Technology and the Levy Institute of Bard College.

- ILO. (2011). “A new era of social justice,” Report of the Director-General, Report I(A), International Labour Conference, 100th Session, Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_norm/@relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_155656.pdf

- ILO. (2016). Women at Work, trends 2016. International Labour Organisation, Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_457317.pdf

- ITUC. (2016) “Investing in the Care Economy: A gender analysis of employment stimulus in seven OECD countries,” Retrieved from https://www.ituc-csi.org/investing-in-the-care-economy

- OECD. (2018a). ” OECD Policy Dialogue on Women’s Economic Empowerment: Recognising, Reducing and Redistributing unpaid care and domestic work Concept Note, Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/development/gender-development/OECD-First-Policy-Dialogue-Womens-Economic-Empowerment.pdf

- OECD. (2018b). “OECD Policy Dialogue on Women’s Economic Empowerment: Recognising, Reducing and Redistributing unpaid care and domestic work summary,” OECD Policy Dialogue on Women’s Economic Empowerment: Recognising, Reducing and Redistributing unpaid care and domestic work Concept Note.

- Ortiz, I.; Cummins, M.; & Karunanethy, K; (2017). “Fiscal Space for Social Protection and the SDGs Options to Expand Social Investments in 187 countries,” Extension of Social Security Working Paper, ESS 048, Geneva: ILO, UN Women and UNICEF.

- OXFAM. (2018). ” Unpaid Care – Why and How to Invest: Policy briefing for national governments,” Retrieved from https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/unpaid-care-why-and-how-to-invest-policy-briefing-for-national-governments-620406

- Parreñas Salazar, R. (2012). “The Reproductive Labour of Migrant Workers.” Global Networks12 (2): 269–275.

- RELAF/UNICEF. (2015). “Application of the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children,” Retrieved from https://www.relaf.org/Guidelines%20FV%20Children.pdf

- Rowntree, O. (2018). “The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2018,” GSMA, Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programmes/connected-women/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2018/

- Samman, E., Presler-Marshall, E., & Jones, N. (2016). “Women´s Work, Mothers, children and the global childcare crisis,” ODI. London. Obtenido de https://docplayer.net/17690651-Women-s-work-women-s-work-global-childcare-crisis-global-childcare-crisis.html

- Scheil-Adlung, X. (2015). “Long-term care protection for older persons: a review of coverage deficits in 46 countries,” Extension of Social Security, Working Paper 50. Geneva: International Labour Organization; 2015.

- Seguino, S. (2013). “Financing for gender equality: Reframing and prioritizing public expenditures,” UN Women. Retrieved from https://www.gender-budgets.org/index.php?option=com_joomdoc&view=documents&path=suggested-readings/seguino-s-paper&Itemid=587.

- Tejani, S. and W. Milberg. (2010). “Global Defeminization? Industrial Upgrading, Occupational Segmentation and Manufacturing Employment in Middle-Income Countries, ” Working Paper 3, Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, New School. New York. Retrieved from https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/images/docs/research/globalization_trade/Tejani%20Milberg%20WP%204.27.10.pdf

- UN Women. (2016). “Redistributing Unpaid Care and Sustaining Quality Care Services: A Prerequisite for Gender Equality,” Policy Brief No.5. New York: UN Women. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2016/unwome

- UN Women. (2015). Progress of the Worlds Women 2015-2016, Transforming Economies, Realizing Rights. New York: UN Women, Retrieved from https://progress.unwomen.org/en/2015/

- UNICEF. (2017). “The State of the World’s Children 2017. Children in a Digital World,” Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/SOWC_2017_ENG_WEB.pdf

United Nations. (1948). “Universal declaration of Human rights,” Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ - United Nations. (2017). “Leave No One Behind: Taking Action for Transformational Change on Women’s Economic Empowerment”. New York, United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2017/3/new-final-report-of-the-un-high-level-panel-on-womens-economic-empowerment

- University of Toronto “The 2014 G20 Brisbane Summit Commitments,” G20 Information center. Retrieved from https://www.g20.utoronto.ca/analysis/commitments-14-brisbane.html

- WHO. (2018). Women on the Move, Migration, Care Work and Health, Retrieved from https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/women-on-the-move/en/

- WHO. (2017). “Human Rights and Health,” Retrieved from https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs323/en/