The burden-sharing problem of forced migration threatens global health and the stability of nations. Previous attempts to address this challenge have not only failed to mobilize collective action but have instead inflicted substantial financial losses of several US$ billion on G20. This policy brief proposes a new approach—the “G2020 Protocol on Forced Migration”—as a global governance framework to efficiently manage the provision and allocation of host capacities. By offering member states different options to support burden-sharing, the framework maximizes incentives for states to join the treaty.

Challenge

With the unpredicted advent of the COVID-19, the world is now facing one of its biggest humanitarian crises since World War II. The spread of the fatal infection has made the provision of medical care capacities to billions of people a critical need. As the crisis continues to unfold, it is becoming evident that the COVID-19 pandemic is exploiting systematic inequalities in health care systems across and within countries.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in 2019, 74.8 million people were forcibly displaced from their homes (UNHCR 2019). Thus, the burden-sharing problem of forced migration is already one of the most pressing global challenges. The spread of COVID-19 has added a new dimension to this problem: First, deteriorating health conditions in developing countries and conflict zones are likely to provoke a new wave of refugees. Second, displaced people have only limited access to health care, housing, and basic sanitation, creating ideal breeding grounds for contagion as well as uncontrolled spread through illegal migration.

The Group of Twenty (G20) countries together host nearly 36% of all refugees. They have previously called to step up coordination and cooperation in order to deal with displacement and migration, support safe and dignified living conditions, enhance refugee self-reliance, and ease financial and social pressures on host countries (G20 2017).

However, previous attempts to mobilize collective action and (re-)allocate the burdens between those who host and those who pay have largely failed: the Dublin Regulation (2003) remains dysfunctional; EU bilateral treaties (EU 2016a, 2016b, 2018) are subject to hold-up problems; and UN Global Compact on Refugees (2018) has fallen short of acquiring the necessary support on various levels. Initial estimates indicate that these inefficiencies have created annual deadweight losses of approximately $55 billion.[1]

The main reason for these problems is disagreement over contributions, that is, “who needs to contribute, how much, and who gets it.” The conflict over contributions is rooted in a mismatch between collective and national incentives (Kaul, Grunberg, and Stern 2003). From a global perspective, all countries would be better off if they voluntarily shared the burdens and contributed to the provision of host capacities. However, from a national perspective, each state has an incentive to freeride on the contributions of others, that is, benefit from stability and societal peace without co-sharing the costs.

The developments before the COVID-19 crisis have already demonstrated that this mismatch cannot be solved through intergovernmental solidarity alone. Many countries have turned to protective measures by reducing their contributions and enacting stricter migration policies. Countries of first asylum, on the other hand, have been forced to continue acting as natural wave-breakers and, thus, they shoulder the most burdens. As COVID-19 aggravates global health and economic disasters, these countries are at risk of overstretching their absorption capacities and their societal and financial resilience.

If the world fails to tackle these problems with an adequate governance system, the inequality in health care systems, as well as the asymmetric distribution of burdens, will destabilize countries of first asylum. This would pose an imminent threat to the safety and dignity of millions, global public health, and economic stability of nations.

Proposal

The following proposal defines the basic principles of a joint action treaty on forced migration. It is analogous to the Kyoto Protocol (UN 1998) and called The G2020 Protocol on Forced Migration (GPFM).

The GPFM is a governance framework established to solve the global public goods problem of forced migration. Central to it is the multinational exchange “Save-the-Dignity” Platform (SDP). By making it the individually best option for states to join from economic and risk management perspectives, the framework is explicitly designed to maximize buy-in by prospective members. More specifically, the GPFM aims to provide an efficient burden-sharing mechanism that:

- Supports safe and dignified living conditions for forcibly displaced people,

- Mobilizes the provision of host capacities,

- Determines the optimal funding structure,

- Reduces uncertainty in terms of finance and ground operations, and

- Redistributes the gains of cooperation in a mutually beneficial way among its member states.

The G2020 Protocol on Forced Migration

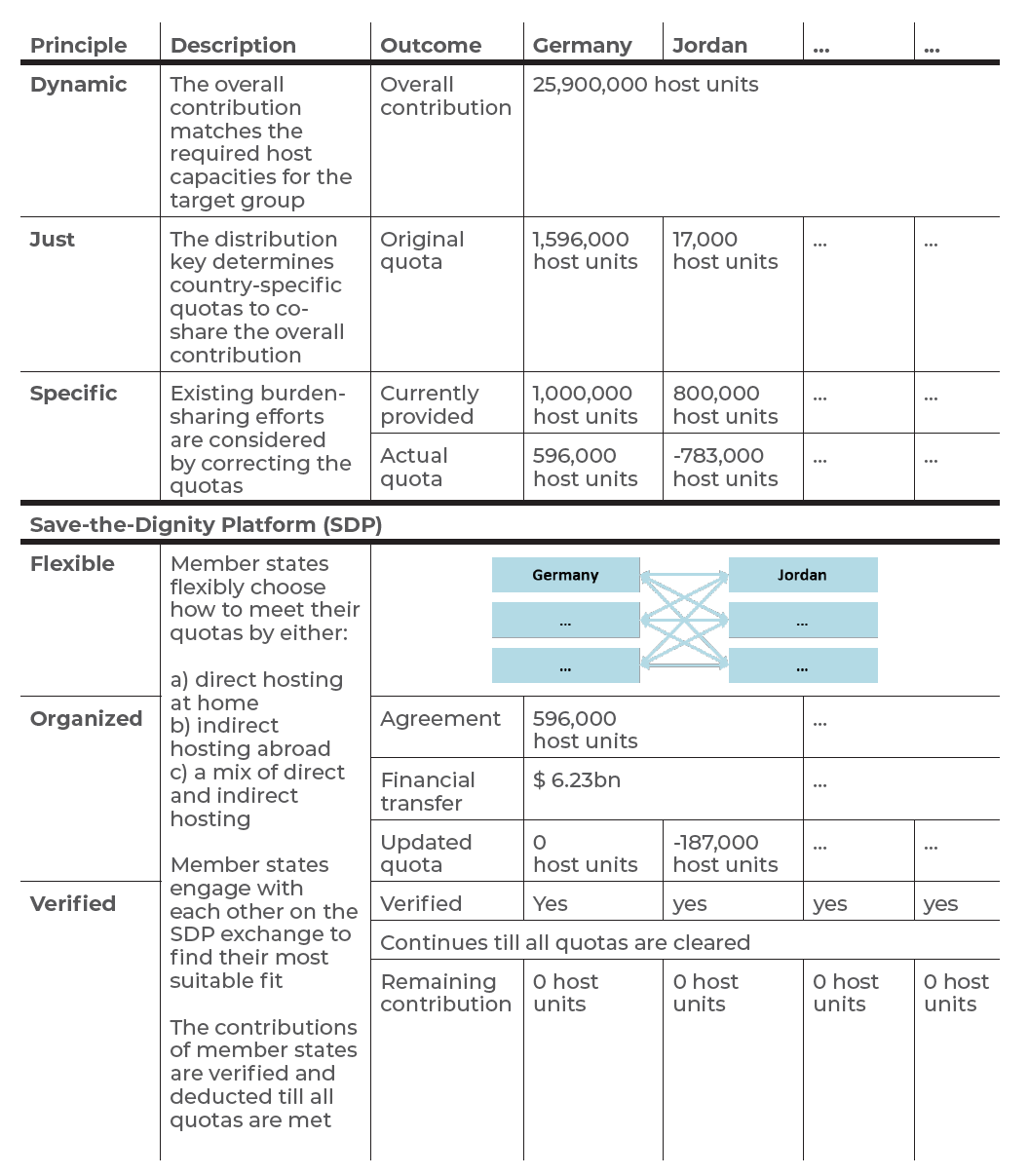

Principle 1: Dynamic

The overall contribution of all member states should correspond to the required host capacities for people in need and thus, be adjusted dynamically. The specific target group is a (sub)set of all forcibly displaced people.

- Operationalization: The GPFM defines the required overall contribution by determining the quantity and quality of host capacities. The quantity is specified by the size of the target group, that is, the direct beneficiaries. To reflect ground realities, the target group does not only include registered refugees, but also individuals seeking complementary forms of protection and persons in refugee-like situations. The quality of a host unit is determined by a set of products and services required, such as health services and basic needs. The overall contribution is updated dynamically, that is, it responds to any increases or decreases in the size of the target group.

- Outcome: The target group is specified, along with the required overall contribution of all member states (in host units).

- Example: The GPFM defines “quantity” and “quality” in line with the UN Global Compact on Refugees (2018) and specifies the minimum requirements for medical care, especially considering the COVID-19 pandemic. The target group consists of refugees. As a lower bound, these beneficiaries require 25,900,000 host units at pre-defined standards.

Principle 2: Just

The overall contribution should be allocated to the member states through a distribution key. This determines country-specific quotas for the purpose of efficiently co-sharing the overall contribution. The key should be based on a just and meaningful indicator of economic resilience.

- Operationalization: The distribution key of the GPFM is a function of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in relation to the total sum of all member countries’ GDPs. The key assigns lower quotas for countries with lower economic power and higher quotas for countries with stronger economies. The quotas are updated regularly to account for changes in the countries’ economic absorption capacities.

- Outcome: The quotas (in host units) are specified per member state.

- Example: Appendix I provides details on how the GPFM assigns quotas to member states. Under the assumption that only those countries may join that have previously voted in favor of the UN Global Compact on Refugees (that is, excluding the US and 11 other countries), the distribution key assigns quotas of around 1,596,000 host units to Germany and around 17,000 host units to Jordan (see Appendix I for the full list of countries).

Principle 3: Specific

When joining the treaty, member states’ actual provisions are likely to deviate from their designated quotas. To account for these specificities, the quotas need to be adjusted with respect to the amount of already-provided host units. The result marks the actual quota of a member.

- Operationalization: Once the quotas are assigned, the UNHCR, or a similar multinational body, assesses the degree of ex-ante fulfillment per member, that is, it determines the gap between the quota and the host units already provided.

- Outcome: The actual quotas (in host units) are defined per member state.

- Example: Jordan currently provides nearly 800,000 host units for refugees. As its original quota is 17,000 units, it provides a surplus of 783,000 host units. Germany currently provides host units for nearly 1,000,000 refugees. With an original quota of 1,596,000 host units, Germany holds a deficit of 596,000 host units.

Principle 4: Flexible

Member states should be able to flexibly choose how to meet their actual quotas, either through financial contributions that support hosting abroad or through direct hosting at home.

- Operationalization: The GPFM acknowledges heterogeneity in how countries are affected by immigration.[2] Therefore, every member state can autonomously and independently make decisions on meeting its actual quota. Three options are available under the GPFM:

- Option Direct: a member state provides host capacities at home

- Option Indirect: a member state finances host capacities abroad

- Option Mixed: a member state chooses a mixture of both

While some countries might have an incentive to offer host capacities if adequate financing is guaranteed, other countries might have an interest in financing hosting capacities abroad. The indirect option allows both types to settle and find an optimal allocation of host capacities given their specific needs and demands. This option is similar to the Kyoto Protocol’s International Emissions Trading Mechanism. However, under the GPFM, an effective transaction requires two states—the host and the financier—in order to agree upon the unit costs. All transactions are made on the SDP (see below for more details).

- Outcome: The actual quotas (in host units) per each member state are updated.

- Example: The provision of one host unit costs Jordan about $3,000 per annum (Haynes 2016: 47); Germany, in turn, needs to spend around $17,900 per annum to provide a host unit (Informationsdienst des Instituts der deutschen Wirtschaft 2016).

- Option Direct: Germany clears its quota by providing 596,000 new host units at home at $10.67 billion per annum (596,000 × $17,900). Refugees who currently reside in Jordan find new homes in Germany; this way, Jordan is relieved from $1.79 billion per annum in costs (596,000 × $3,000).

- Option Indirect: Germany and Jordan agree to unit costs per annum of, for example, $10,450 for 596,000 host units. Germany transfers $6.23 billion (595,000 × $10,500) to Jordan and 596,000 refugees continue to reside in Jordan. In this scenario, each country gains $4.44 billion per annum compared with the “direct” option (Germany: $10.67–6.23 billion, Jordan: $6.23 billion–1.79 m). For Germany, this option also generates actual savings: It currently spends around $9.38 billion per annum to prevent forced migration (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 2020). Under the indirect option, Germany would only need to spend $6.23 billion, realizing savings of around $3.15 billion per annum (or 34% of its current transfers).

Under either option, Germany’s deficit is cleared, and Jordan’s surplus reduces to 187,000 host units (783,000—596,000).

Principle 5: Organized

States should engage in a multinational exchange platform to determine the most efficient way of cost-sharing. Such an exchange continues until all quotas are cleared.

- Operationalization: Under the GPFM, the SDP, an intergovernmental exchange platform that balances member states’ surpluses and deficits, is established. It allows its members to choose between the direct, indirect, and mixed options to clear their respective quotas. The direct option is a default option, that is, if members cannot agree on another option, host capacities must be provided at home. The SDP is hosted and organized by the UNHCR or a similar multinational body.

- Outcome: All actual quotas (in host units) of all member states are cleared.

- Example: Jordan, Germany, as well as other GPFM members engage on the SDP. As the unit costs for hosting vary by country, all states individually determine the most suitable option that helps meet their specific needs and demands. Jordan, for instance, is unlikely to accept a host unit cost of $3,000, whereas Germany would reject a transfer of more than $17,900 per host unit. The settling process continues until all deficits and surpluses are cleared.

Principle 6: Verifiable

The member states’ efforts to meet their quotas should be tracked and validated regularly. This requires clear-cut definitions that close loopholes and backdoors.

- Operationalization: A significant challenge of the Kyoto Protocol’s instruments is the verification of contributions. Although this problem is less pronounced in the case of host units, verification still needs to be considered. Thus, the GPFM defines a default reporting period, for example, a period of one year following the release of the latest statistics by the UNHCR. Shortly after the beginning of a new reporting period, the opening phase of the SDP begins. During this phase, all quotas need to be cleared by GPFM members. If two states agree on the indirect option, the financier reports the details to the multinational body that operates the SDP. Only after the host country concurs, the respective updates to the quotas are made.

- Outcome: The cleared quotas (in host units) per member state are externally verified.

- Example: If Jordan and Germany agree on the indirect option, Germany reports the details, that is, the number of host units, agreed host unit costs, and financial transaction data, to the SDP organizers. The organizing body requests Jordan to concur. If Jordan confirms in the affirmative, the agreement becomes a legally binding contract and corresponding adjustments are made to both states’ quotas.

Basic Architecture

Expected Results

The GPFM provides the framework for an efficient burden-sharing mechanism. Member states engage in intergovernmental exchange to find their best fit, that is, a state’s optimal combination of hosting at home and financing abroad. The framework is likely to produce two types of members:

- Host countries, that is, countries offering more host capacities at home than required by their quota, and

- Financing countries, that is, countries that meet the majority of their quota by funding host capacities abroad. This outcome has important implications for refugees, member states, and global coordination.

Impact on Refugees

Result 1 (Protection): By definition, all forcibly displaced people who are targeted by the GPFM find adequate protection, health care, and humanitarian assistance.

Most beneficiaries of the GPFM will likely be able to stay close to their countries of origin. For the individual, this might be preferable because host societies often share the same language and similar cultural and religious contexts. Social ties, such as with relatives and friends, may exist. These are important not only for trauma recovery and mental health, but also for establishing a new existence with better economic opportunities.

Result 2 (Perspectives): Under the GPFM, targeted refugees are offered better chances for a life in dignity, including improved mental health, social safety, and economic opportunities.

Impact on Member States

Many financing countries currently incur financial losses because of inefficient allocations of resources. GPFM members are likely to recover (parts of) these losses and thus, set strong incentives for prospective members to join the treaty even when assuming strict rationality and self-interest. Germany, for instance, would be able to fully offset its quota by spending only 66% of its current budget and, as a result, making actual savings of $3.15 billion per annum.[3]

Result 3a (Financial Incentives I): The GPFM guarantees that financing countries find the most feasible option to meet their obligations. They can redirect their existing budgets to alternative and more efficient allocations, realizing actual savings in return. The GPFM is designed to directly carry over parts of the recovered gains to host countries. As previously shown, Jordan would realize net gains of $4.44 billion per annum by providing host capacities on behalf of Germany.

Result 3b (Financial Incentives II): The GPFM ensures that host countries receive adequate financial transfers if they continue to provide host capacities on behalf of others. As host countries determine the minimum acceptable unit costs themselves, transfers can include premiums to lift the living standards of local communities.

Besides these financial incentives, two additional effects render it advantageous for states to join the GPFM.

Result 4 (Insurance Effect): The GPFM offers its members exclusive insurance against exogenous shocks and regional disasters. By sharing the costs and updating obligations dynamically, each member state is protected against facing the consequences of instability alone.

Result 5 (Justification Effect): The possibility of choosing how to meet quotas provides member states with an instrument to flexibly respond to changes in public support. This aspect may be relevant for societies wherein parts of the population are skeptical of a government’s refugee policy.

Impact on Global Coordination

As an initial estimate exemplifying the financial dimensions, the G20 countries appear to lose around $55 billion every year because of inefficient allocations of resources.[4] The GPFM is designed to minimize this deadweight loss and elevate the unexploited gains of collective action with the aim to set member states financially better off than without the GPFM.

Result 6 (Global Coordination): The more that countries join the GPFM as members, the more does effective its mechanism become in minimizing the total burden. As the financial returns are directly internalized by its members, the GPFM demonstrates the increasing returns on investment of mutually beneficial cooperation.

Result 7 (Global Norms): Global public goods are often accompanied by moral loading. As a technical framework designed to find the optimal solution for an allocation problem, the GPFM does not entail such normative statements. This may help shift the focus to more solution-oriented approaches in coping with other challenges (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic or climate change).

G20 Recommendations

The policy brief suggests that the G20 leaders call for negotiations on the GPFM. Analogous to the stages preceding the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol, a working group could be formed that leads a cooperative and collaborative process with other bodies. More specifically, the following statements could be adopted in the G20 Leaders Declaration:

- Large movements of refugees continue to be a global concern with major humanitarian, political, social, and economic consequences.

- We re-emphasize the urgent need for improving the global governance of forced migration and, at the same time, recognize the sovereignty of all countries in responding to forced migration based on their capacities and capabilities.

- We therefore ask the UNHCR, in cooperation with the World Health Organization and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, to develop a joint action treaty on forced migration that reduces uncertainty and balances national interests in an efficient, flexible, and fair manner.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Betts, Alexander, and Paul Collier. 2017. “Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System.”

International Journal of Refugee Law 30, no. 1: 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eey015.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 2020. “Asylbedingte Kosten und Ausgaben.”

Accessed June 05, 2020. https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/flucht/zahlenzu-asyl/265776/kosten-und-ausgaben.

Dublin Regulation. 2003. “COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No. 343/2003.” Official Journal

of the European Union, L (50/1).

EU. 2016a. “EU—Lebanon Partnership. The Compact.” Accessed February 10, 2020.

https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/lebanon-compact.pdf.

EU. 2016b. “EU—Jordan Partnership. The Compact.” Accessed February 10, 2020.

https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/jordan-compact.pdf.

EU. 2018. “EU—Turkey Statement. Two Years On.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20180314_eu-turkey-two-years-on_en.pdf.

G20. 2017. “G20 Leaders ́ Declaration. Shaping an Interconnected World.” Hamburg.

Accessed, February 10, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_17_1960.

Haynes, W. 2016. “Jordanian Society’s Responses to Syrian Refugees.” Military Review

January–February: 45–52.

Informationsdienst des Instituts der deutschen Wirtschaft. 2016. “Was Kostet

die Flüchtlingshilfe?” Accessed June 05, 2020. https://www.iwd.de/artikel/was-kostet-die-fluechtlingshilfe-256373.

Kaul, Inge, Isabelle Grunberg, and Marc Stern. 2003. “Defining Global Public Goods,”

In Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century, edited by Inge

Kaul, Isabelle Grunberg, Marc Stern, 2–19. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195130529.001.0001.

UN. 1998. “Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate

Change.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/

kpeng.pdf.

UN Global Compact on Refugees. 2018. “Report of the United Nations High Commissioner

for Refugees. Part II Global Compact on Refugees.” General Assembly Official

Records, 73rd Supplement No. 12. https://www.unhcr.org/gcr/GCR_English.pdf.

UNHCR. 2019. “Global Report 2018.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2019/pdf/GR2019_English_Full_lowres.pdf#_ga=2.167001914.545341269.1597366119-109961812.1597366119.

World Bank. 2020. “World Bank National Accounts Data, and OECD National Accounts

Data Files.” Accessed June 07, 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD.

Appendix

[1] . See later sections for details

[2] . Estimates indicate that the cost to host a refugee in a developed economy is $135, but $1 in less developed economies (Betts and Collier 2017).

[3] . $9.38–6.23 billion; see Principle 4.

[4] . Assumptions: 1) the US and eleven other countries do not join the GPFM; 2) G20 financing countries provide host capacities for 3.7 million refugees at home (excluding Turkey); 3) cost differentials between Germany and Jordan apply, on average, to all financing and host countries.