Fueled by major disruptions in the technological landscape, a process of Schumpeterian creative destruction is underway. In the Argentine presidency, the G20 affirmed that it was fully committed to deliver the policy responses and international cooperation that will help ensure that the benefits of the technological transformation are widely shared. A special focus was put in considering individual country circumstances when analyzing challenges and benefits – particularly in emerging economies. In this policy brief, we build country-specific data from three G20 countries –and other countries- to ask to what extent Latin America is ready to reap the benefits of this revolution.

Challenge

Artificial intelligence (AI) and other digital technologies are changing the way we produce, consume, trade and work. According to the most accepted global narrative, the negative impacts of digital transformation on labour markets will be temporary and a new equilibrium will be eventually attained, based on a full absorption of new technologies and the complete acquisition of the relevant skills by workers.

During the Argentine presidency, the G20 agenda focused on the following pillars: the future of work, infrastructure for development, a sustainable food future and a gender mainstreaming strategy. In the final declaration, G20 leaders affirmed that “Transformative technologies are expected to bring immense economic opportunities, including new and better jobs, and higher living standards. The transition, however, will create challenges for individuals, businesses and governments. Policy responses and international cooperation will help ensure that the benefits of the technological transformation are widely shared” (G20, 2018). Furthermore, they committed to develop a ”Menu of Policy Options for the Future of Work (…) considering individual country circumstances” (G20, 2018). The T20 made its contribution by proposing the G20 to “ensure that the menu of policy options for the Future of Work is flexible enough to address the heterogeneity of challenges that G20 countries face” (T20, 2018).

In this Policy Brief we build country-specific data to assess the reskilling challenge in three G20 countries (Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico) plus a subset of Latin American countries. Our main conclusion is that domestic factors matter. In Latin America, a key challenge for seizing the benefits of technological change is the reskilling of current and future workers so that they are able to complement emergent technologies. Latin America needs to make a big reskilling effort in order to reap the benefits of the 4IR: about half of its current workers face the direct competition of new technologies. It is particularly challenging in the short run, as less than one every six workers has the right skills to complement the new machines (in the US it’s one every three). The menu of policy options must take into account these heterogeneities.

Proposal

Technological change and the future of work in the North

Artificial intelligence (AI) and other digital technologies are changing the way we produce, consume, trade and work. This profound transformation resembles those brought by the steam engine in the late eighteenth century, electricity and assembly lines in the late nineteenth century and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) by the end of the 20th century –the first, second and third industrial revolutions, respectively–. These new machines or robots perform very complex cognitive tasks that a few years ago were limited to the human domain, such as facial recognition, the processing and translation of natural language or the recognition of written characters. By augmenting the power of existing ICTs they also extend the ability of machines to master standardized and routine tasks. This change is so profound that many wonder if we are experiencing a new “Cambrian explosion” –that period of accelerated diversification of living organisms about 500 million years ago– that, this time, affects machines. It is no coincidence, then, that we are now talking about the fourth industrial revolution (or 4IR).

Labor markets are deeply challenged by these technological disruptions. Indeed, some alert that we are facing the obsolescence of a great part of the workforce and the disintegration of traditional labor markets institutions (Mokyr et. al., 2015). However, beyond the anxieties in the media and public opinion, both government and business leaders around the globe think that in the long run both employment and real wages are expected to grow due to technological change. Excess of workers in occupations where new technologies are expected to replace human will be absorbed by an increased labour demand in activities where these technologies makes humans more productive (see IMF 2018 and Blit et al. 2018). Even if the 4IR seems to go beyond previous revolutions, threatening high skilled workers, its impact should be similar to earlier disruptions. Eventually, workers will acquire the skills that complement these technologies. Therefore no big job losses are expected, but working hours might decline leaving more time available for the consumption of leisure (indeed, nothing different from former technological revolutions –see Fogel, 2004).

To sum up, a process of Schumpeterian creative destruction –similar to those ones observed in previous industrial revolutions– is underway. According to the most accepted global narrative, the negative impacts of digital transformation on labour markets will be temporary –except for the obsolescence of traditional labour institutions–. A new equilibrium will be eventually attained, based on a full absorption of new technologies and the complete acquisition of the relevant skills. Meanwhile, as it happened during former revolutions, there will be a race between technology and skills, that is, between the adoption of new technologies and the reskilling of the workforce (Goldin and Katz, 2008) (1). During this race frictions between supply and demand of labour will appear, and this may be reflected in rising income inequality and increased political tensions.

Is Latin America Ready? Reskilling efforts required to bring the 4IR to Latin America

In a recent study, Albrieu et al. (2018) calibrated a growth model augmented by AI for simulating alternative growth trends in LAC, conditional on the adoption and diffusion of AI-related technologies and its impact on the growth of the entire economy and some economic sectors in particular during the next twenty years. They found that a fast adoption and diffusion of new technologies –faster than the regional performance in past industrial revolutions– can accelerate growth by 1% per year. A “business as usual” or “status quo” pattern of technological change, in turn, yields a growth pattern similar to the one observed in the past, when LAC lagged behind other successful regions (such as Emerging Asia). Is LAC ready to break with its past and seize the growth benefits of global technological change? Technological change is not automatic. Instead, it requires the timely availability of dynamic companies that can absorb the emergent technologies and a workforce that has the skills, abilities and knowledge compatible and complementary to these technologies. In past industrial revolutions, countries that lagged behind were populated by firms and workers that weren’t ready to run the race between technology and skills.

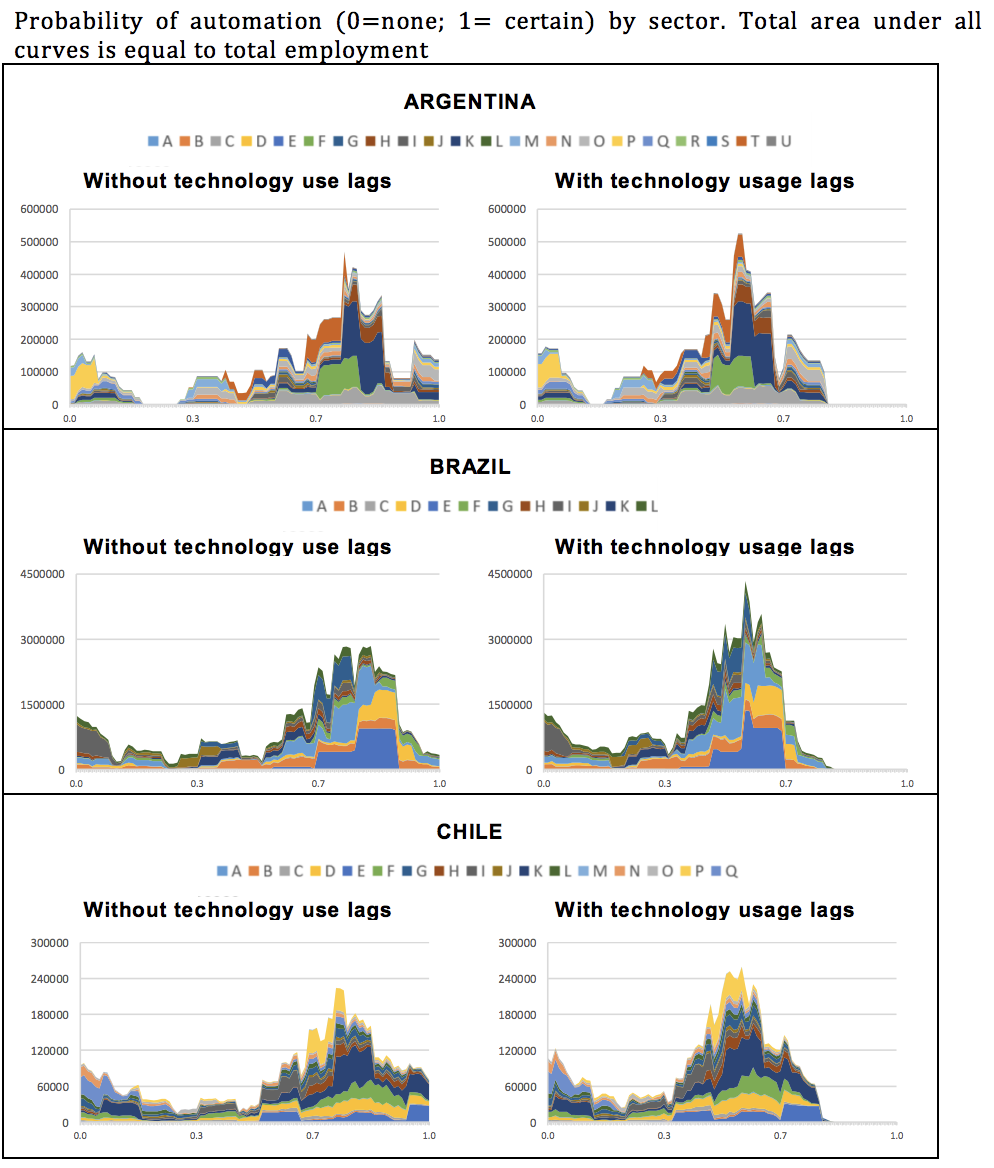

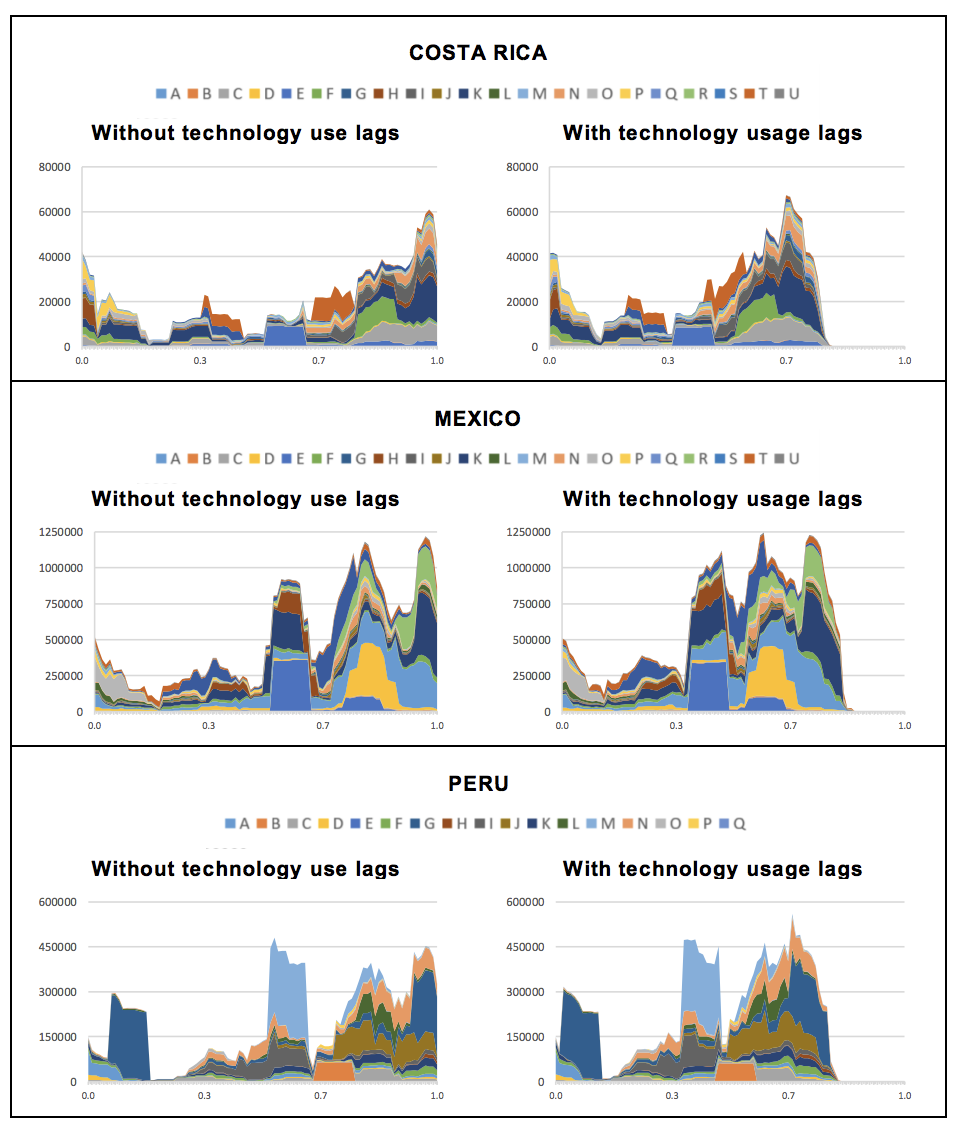

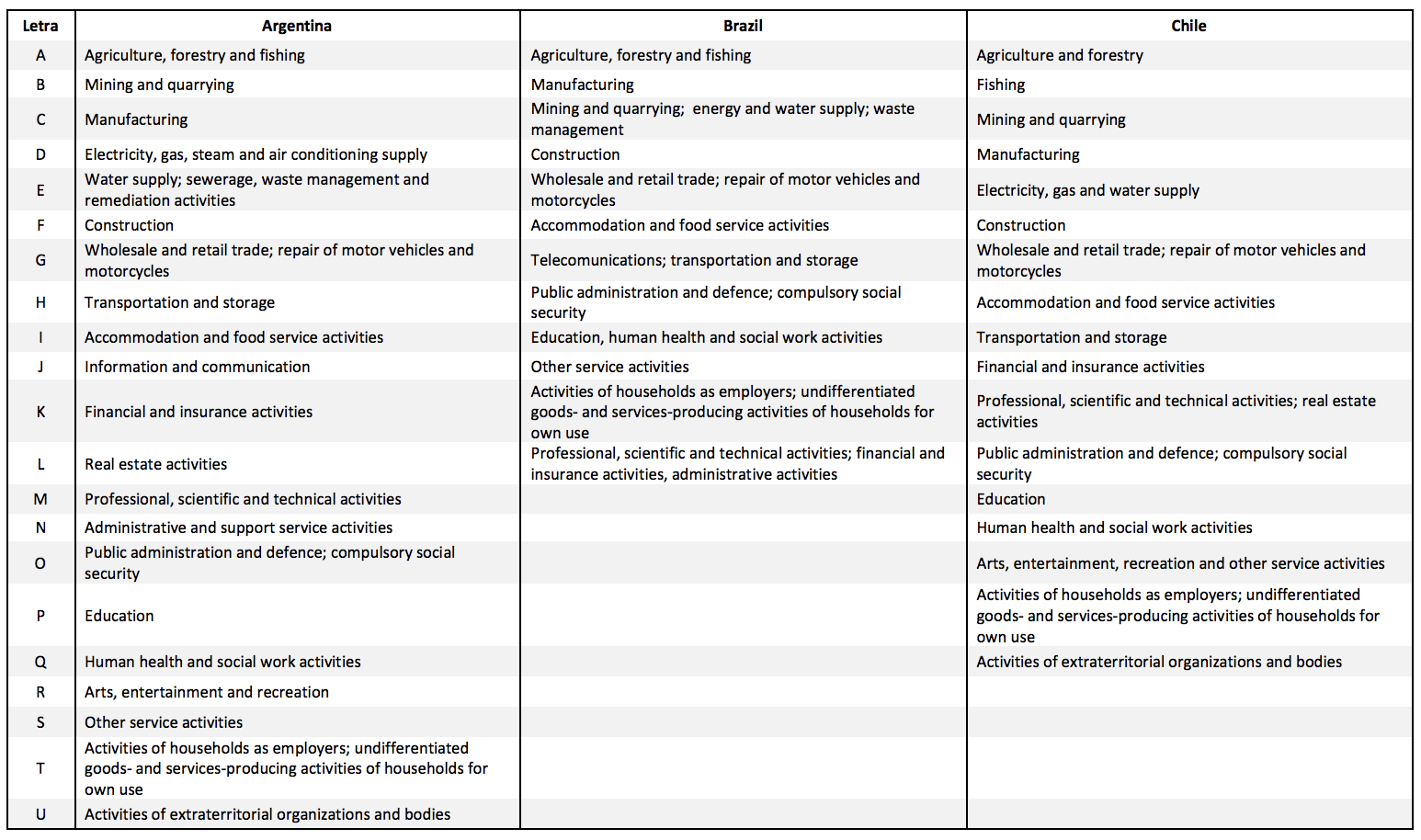

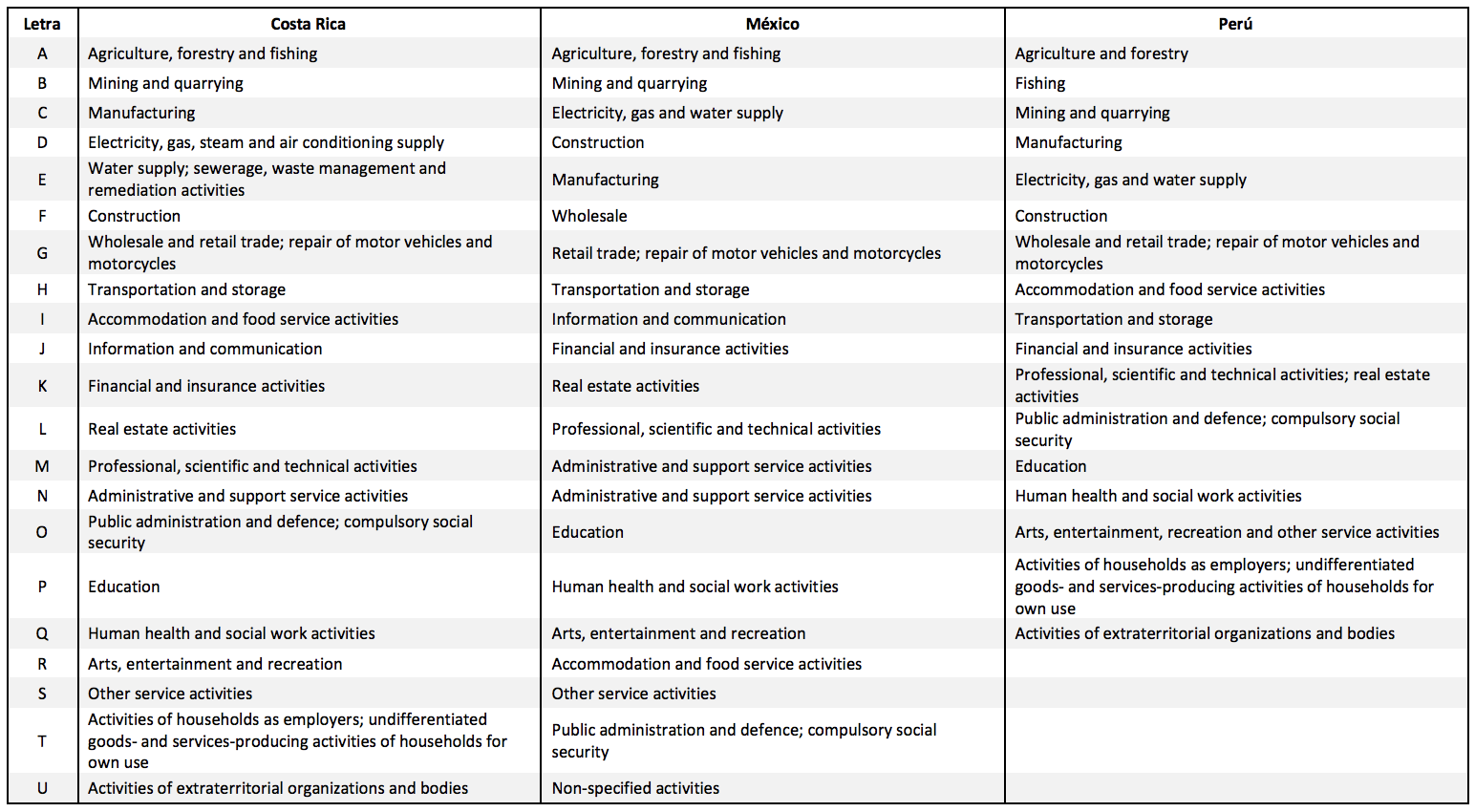

Thus, a key challenge is the reskilling of current and future workers so that they are able to complement emergent technologies. They must be capable of moving across the skill spectrum to concentrate its activities in those tasks where machines are not good enough (intensive in perception and manipulation in complex contexts, creativity and social intelligence). Are LAC workers ready? To answer this question, Albrieu and Rapetti (2019) estimated the reskilling effort in LAC under alternative scenarios of technological change (and economic growth) (2). The analysis follows the influential study of Frey and Osborne (2017) to estimate the probability of automation –or the reskilling effort– of the current occupations in six key LAC economies (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru). Given that in the past, these countries adopted technologies with a considerable time lag with respect to leading economies, such as the US, in the estimation we consider alternative scenarios of technology adoption. In these scenarios, the estimated probabilities include a factor that corrects for the time lag considered in each scenario. More precisely, we adjusted probabilities according to the average time lag observed during the 90s, 80s and we also considered an scenario in which adoption takes place as fast as in US and then correct these figures to allow for time lags in technological adoption and diffusion (3).

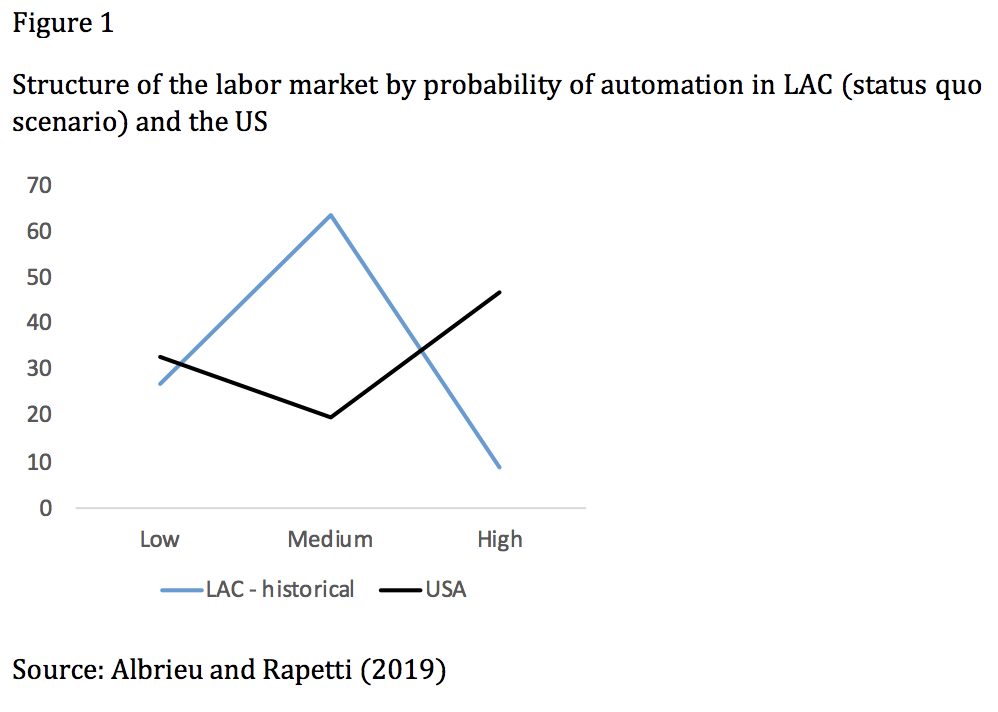

The first conclusion of this exercise is that in the status quo scenario –where LAC follows a historical pattern of adoption and diffusion of emerging technologies– the reskilling effort is relatively low (Figure 1). Around 7% percent of current workers, that is, about 12 million people, will need to readequate their skills and move to high-productivity jobs. This is a low share compared with dynamic economies such as US, where as much as 47% of the labor force is in this situation. Interestingly, the pattern of risk of automation / reskilling effort in LAC in this scenario is the exact opposite to the one found in the US. While there’s a “hollowing out” across the reskilling effort in the North, it seems to be a “hollowing in” in LAC.

Note that the low level of reskilling needed in this scenario is a direct consequence of the slow pace of technological change. Put it simple, in this scenario the 4IR happens elsewhere but in LAC. Economic growth in the region remains subdued, diverging from the one observed in the dynamic economies of Emerging Asia.

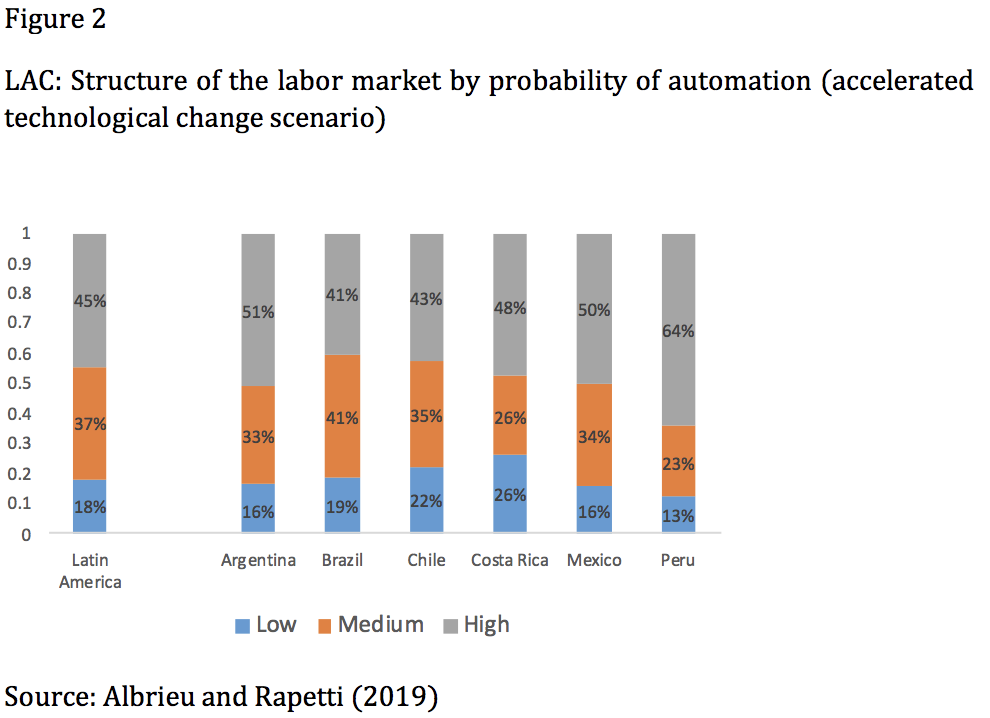

How big is the reskilling effort if we want LAC to catch the wave of the 4IR? The effort is huge: in order to be able to fully absorb emerging technologies – and accelerate economic growth– some 45% of current jobs (that is 81 million workers) needs a complete redefinition of its task content in order to survive (figure 2). This figure pose a big challenge for existing workforce skills development systems in LAC over the next 5 / 10 years, particularly in Peru, Argentina, and Mexico.

A closer look at the data shows that at the same pace of technological change, challenges are more “front-loaded” in LAC than in the US. The shortage of labor force with the skills complementary to AI and other associated technologies could be an obstacle to the growth of Latin American economies even in the short run. In LAC the number of workers with the right skill bundle amounts to about 32.8 million out of a total of 182 million, that is, about 18% of the total employed population, while in the US it reaches 33%. The skill shortage represents a short-run obstacle to technological transformation and growth particularly high in Argentina, Peru, and Mexico, while Costa Rica seems better prepared.

Naturally, there are important contrasts between sectors according to the degree of susceptibility to automation of tasks and occupations, not only between countries but also between sectors (see Apendix). An eloquent example is that of construction, which employs approximately one-tenth of the total number of employed persons in each country taken into consideration. Of the occupations covered, more than two thirds are in the high probability zone of automation in all countries.

The trade sector, both wholesale and retail, is also a great source of employment throughout Latin America: in each country it employs around 20% of the workforce. On average, 65% of jobs in this area are at high risk of being automated. However, there are discrepancies between countries: Peru is the country with the lowest percentage of employment with a high risk of being automated in this industry –around 50%–. At the other extreme, stands Argentina, with 84% of occupations of the trade sector at high risk of automation (which threatens a sector that explains 18% of total employment).

The occupations associated with education and health and social services represent very different cases from the previous ones. In these jobs, the tasks are as susceptible of subject to automation and the ability of workers to adapt to circumstances that are difficult to anticipate means that these occupations have the least risk of automation in all LAC countries. The discrepancies at the country level are small, with percentages of high-risk employment in education and health sectors close to 10% and 20%, respectively.

Policies to break the status quo and prepare LAC workers for the 4IR

LAC needs to do a big reskilling effort in order to reap the benefits of the 4IR: about half of its current workers face the direct competition of new technologies. It is particularly challenging in the short run, as less than one every six workers has the right skills to complement the new machines (in the US it’s one every three).

What to do? We briefly build the menu of policy options for LAC –with commonalities and differences with those needed in high-income countries.

Available evidence shows that enhancing socio-emotional and cognitive skills is a necessary condition for the 4IR, even when other complex skills will be needed in specific sectors. Flexibility and adaptability capacities will also be crucial, and these are possible only if expertise is acquired throughout life (lifelong learning) rather than during a specific phase or period. As a consequence, current and future workers reskilling will be a challenging goal since it involves numerous learning stages, from early infancy to professional training.

Ideally, in this dynamic context the best option would be to set up a specific public agency that tries to anticipate labour challenges, reform the current skills development system, and evaluate the outcomes. There, the mix of data about labour markets and prediction models could work as a policy guide to design and implement education policies and incentive mechanisms that encourage professional training inside companies.

If the creation of an agency of this kind was not possible, there are several specific policies that can make the difference:

• A comprehensive diagnosis about the state of knowledge and workers’ skills is needed. In high-income countries a lot of data has been built over the last years, but it is not the case in LAC.

• Early childhood learning should be encouraged. At that time brain structure is settled, and is a key period to develop basic cognitive and socio-emotional skills. Early childhood learning systems are severely underdeveloped in LAC if compared with high-income countries.

• Even though basic education coverage has been broadened, a higher quality education is necessary to acquire better and more advanced skills and knowledge. Again, the differences between high-income and LAC countries in terms of education quality is startling.

• Higher education should be adapted to facilitate the transition to the labour market. Learning mechanisms and professional training systems should be enhanced.

• Training systems within firms should be updated on a regular basis to cope with rapid technological change.

These policy recommendations may seem ambitious if we take into account that LAC find it hard to reform and adapt their policy schemes and institutions to sudden changes in the context. In terms of the G20 agenda, this piece of evidence points to fundamental differences in the challenges and benefits posed by the 4IR across high income and LAC countries. It, in turn, supports the G20 strategy of focusing on differences and heterogeneities if the goal is to foster a 4IR for the benefit of all.

REFERENCES

• Albrieu, R. Rapetti, M.; Brest López, C.; Larroulet, P.; and A. Sorrentino (2018), Artificial Intelligence and Economic Growth Opportunities and Challenges for Latin America. Working paper, CIPPEC-Microsoft Latin America.

• Albrieu, R. and M. Rapetti (2019), “Technological Change and The Future of Work in Latin America.” Mimeo, CIPPEC.

• Blit, J.; Amand, S.; y J. Wajda (2018), “Automation and the Future of Work. Scenarios and Policy Options”. CIGI Papers No. 174.

• IMF (2018) “Technology and the Future of Work”. IMF Staff Note, April 11.

• Fogel, E. (2004), The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100. Cambridge University Press.

• Frey, C. B., and Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological forecasting and social change (114), 254-280.

• G20 (2018), “Building consensus for fair and sustainable development”

• Goldin, C. Y L. Katz (2008), The Race between Education and Technology. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

• Mokyr, J.; Vickers, N.; y N. Ziebarth (2015), “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29 (3): 31-50.

• T20 (2018), “Communiqué”. • World Bank (2019), World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work.

APPENDIX