Multi-stakeholder partnerships are of great relevance in international development cooperation and foreign aid. Data is also critical in supporting this field, but it is difficult to obtain updated information about G20 members’ respective actions and budgets, mainly due to insufficient institutionalisation within multilateral organisations and low levels of data systematisation and transparency at the national level. In view of this, I assess updated information about G20 members’ policy priorities, and present a brief account of the scenario, including how the OECD’s Official Development Assistance and South-South Cooperation contribute to Sustainable Development Goal #17, particularly against the critical juncture of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, I spell out key challenges for G20 members as foreign aid providers and SSC partners, and propose the creation of a Working Group on International Development Cooperation and Foreign Aid (WGIDCFA) within the T20.

Challenge

As the world is still struggling to recover from a global health challenge, while at the same time confronted with mitigation, adaptation and compensation challenges associated with climate change, understanding risks, uncertainties, and vulnerabilities as socio-political and economic processes has become a key global policy concern. Designing effective public policies to cope with the effects, while dealing with the root causes, of global health pandemics and the current climate emergency, implies ensuring solid and institutionalised levels of international cooperation. States alone cannot provide effective answers to these challenges. No borders, no military power, no economic capacity has been able to hold back the worldwide dissemination of SarsCov-2. The complexity of pandemics and climate change links the local and global scales, as well as natural and social conditions, making it necessary to grasp where such scales and conditions intersect to be able to analyse their spatial, political and sociological consequences. Aside from climate change and health pandemics, other cross-border threats to all sorts of global collective action may be part and parcel of the same reasoning and policy efforts, such as biodiversity losses, unsustainable development practices and financial crises. A successful sustainable development agenda requires inclusive partnerships within and across nations that should involve different levels of government, the private sector and civil society. Such partnerships must be built on principles and values, but also on shared goals that place human beings, the environment and the biosphere, as well as sustainable livelihoods and life-styles, at the centre of all development strategies. Poor institutionalisation of policy dialogues at the multilateral level and low levels of data systematisation and transparency may hinder the sound implementation of the 2030 Agenda. The G20 assembles a diverse set of major global economies that also play a leading role in international development cooperation, either as major foreign aid donors or as South-South cooperation partners. OECD-DAC members are able to disseminate data through a series of well known worldwide platforms, unlike the Non-DAC; in the G20 there are 11 OECD-DAC members. This policy paper aims to discuss considerable challenges that the G20 faces to mobilise and redirect the much needed transformative power of reviewing and monitoring frameworks, regulations and incentive structures that should foster private and public investments to reinforce sustainable development. Considering this main goal of this policy paper, three specific questions summarise the cross-national analysis that will be undertaken. Firstly, what is the situation in terms of production of updated information by G20 members on their respective development cooperation budget allocations? Second, what is the scenario portrayed for the OECD’s Official Development Assistance and South-South Cooperation in achieving Sustainable Development Goal No.17 (SDG#17), particularly within the context of post-COVID-19 challenges? Thirdly, what are the outstanding domestic challenges that G20 members are confronted with when it comes to analysing and defining their roles as foreign aid providers and SSC partners? The main assumption in this policy paper is that multi-stakeholder partnerships are of great relevance in the field of international development cooperation, and that poor institutionalisation of policy dialogues at the multilateral level and low levels of systematisation and data transparency may hinder the sound implementation of the 2030 Agenda.

Proposal

INTRODUCTION

This paper adopts a three-tier approach, aiming to provide a comprehensive framework of how international development cooperation and foreign aid can foster future scenarios where strong multi-stakeholder partnerships are a key tool in the implementation of SDG#17 (Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development). Firstly, I argue that there is a need to assess how updated information is produced and disseminated about G20 members’ respective development cooperation and foreign aid. Secondly, I present a brief account of the scenario on how the OECD’s Official Development Assistance and South-South Cooperation (SSC) contribute to SDG#17, particularly within the context of post-COVID-19 challenges. Thirdly, I analyse some domestic challenges that G20 members are confronted with when it comes to defining their roles as foreign aid providers and SSC partners.

PRODUCING AND DISSEMINATING COMPARABLE DATA ON INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AND FOREIGN AID

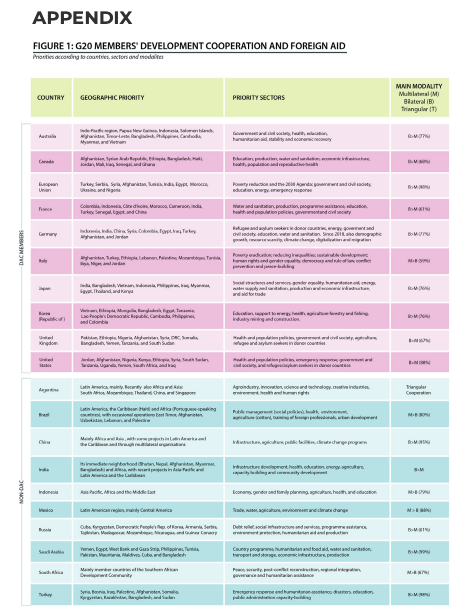

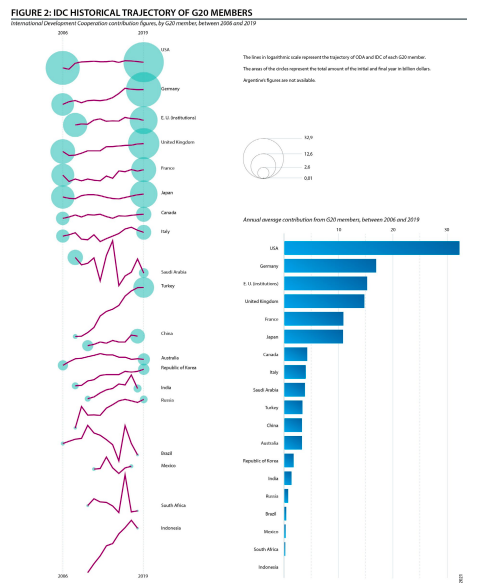

Scholarly research and expert reports published by international NGOs and think-tanks have shown how hard it is to find updated information about G20 members’ respective development cooperation and foreign aid, their priorities and budget allocations (Besada and Kindornay 2013; Development Initiatives 2013; Develtere et al. 2021; Lancaster 2007; Purushothaman 2020). Our condensed effort in compiling data for this policy paper also revealed absences and gaps in systematically updated online platforms, wherein data, case descriptions and assessment reports, inter alia, could cover the reality of G20 members and be made available to the public worldwide (Figures 1 and 2). If such a platform existed, the task of quantitatively and qualitatively presenting, measuring and analysing the outcome, impact and contribution of IDC and foreign aid towards the implementation of Agenda 2030, with particular reference to SDG#17, would be considerably less challenging.

Among G20 countries, OECD-DAC members already share a common history in constructing norms, defining criteria and putting together methodologies to conceive their foreign aid programmes, monitor and evaluate their results, and disseminate data through a well known series of worldwide platforms, such as Aid for Trade, Development Cooperation Working Papers and DAC Peer Reviews. The annual Development Co-operation Report covers a wide range of comparable data, thus helping improve knowledge of the foreign aid and Official Development Assistance (ODA) practices implemented by DAC members (OECD, 2020). Initiatives taken by international NGOs and platforms such as the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), Development Initiatives and the Publish What You Fund global campaign attempt to further the OECD’s efforts and fill the gaps.

For historical and political reasons, despite their rising numbers, donors and development cooperation partners, as many of them prefer to label their profile and role in this field of international relations, have not established an institutional stance comparable to the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee. They have so far mainly used the United Nations Development Cooperation Forum (DCF) as a universal policy dialogue forum, including all UN members, civil society organisations, international organisations and development banks, local governments, philanthropic foundations and private-sector actors. Nevertheless, the DCF only reviews trends and progress in international development cooperation, and encourages coordination; it lacks administrative, political and financial support to define and implement monitoring, evaluation and assessment tools in the field of international development cooperation. Aside from the DFC, policy dialogues and on-the-ground coordination efforts among non-DAC members occur only occasionally: for instance, when the United Nations organise a conference (such as PABA+40 in Buenos Aires in 2019), within the recently established United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation (2012) and its South-South Galaxy platform, or through trilateral cooperation programmes that may involve industrialised and SSC partners, as well as multilateral organisations (FAO, UNDP, UNESCO, WFP, WHO, among others).

With the proliferation of so-called “new actors” in the field of international development cooperation, not only was the States’ monopoly in development cooperation broken, but the role played by DAC members was also challenged. Among G20 members, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Turkey were pioneers in taking up a proactive role in development cooperation as donors or partners: the Saudi Fund for Development was created in 1974, the Brazilian Cooperation Agency in 1987 and the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency in 1992. Almost all other non-DAC countries who are also G20 members have more recently set up an agency, a development cooperation fund or a public administration responsible for coordinating the cooperation provided. That has been the case of the Agencia Mexicana de Cooperación Internacional al Desarrollo/AMEXCID (Mexico, 2011), the Development Partnership Administration/DPA (India, 2012) and the China International Development Cooperation Agency/CIDCA (2018).

As for private-sector and civil society organisations, some non-governmental organisations, particularly American foundations and European agencies such as NOVIB and OXFAM, have been working in this field since at least the 1950s. In the 21st century, however, there has been an increase in both the amount and visibility of non-governmental international cooperation. In public health and environmental protection, for instance, the following public-private alliances, among others, have resulted in the establishment of funds and organisations: GAVI (Global Fund against AIDS), IFFM (International Finance Facility for Immunization, associated with GAVI), UNITAID (United to Provide AID, the entity that manages the International Drug Purchase Facility, created in 2006 to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis), Clean Development Mechanism (under the Kyoto Protocol) and GEF (Global Environmental Facility, created in the midst of Rio-92).

As a result, the problem of harmonisation of actions and institutional channels is a major challenge for the international community and G20 members. While the average number of donors per country was 12 in the 1960s, it increased to 33 in the years 2001-2005. In 2007, there were more than 230 international organisations, funds and programmes working in the field of international development cooperation (IDA 2010). Therefore, the current scenario is much more complex and multi-faceted. The boundaries between public and private solidarity are increasingly unsettled, beneficiary countries also define their agendas as donor/partner countries. However, heterogeneity and pluralisation in the current “market for aid” (Klein & Harford 2005; Mavrotas & Nunnenkamp 2007) may also imply uncertainties and risks for aid effectiveness and development cooperation partnerships.

Fragmentation is one of them: there are 80,000 new projects each year, financed by at least 42 donor countries, through 197 bilateral agencies and 263 multilateral organisations (Kharas 2010, p. 4). Lack of coordination and policy incoherence are other critical bottlenecks that hamper the effectiveness of development cooperation: Cambodia alone is reported to have received around 400 donor missions per year on average, followed by Nicaragua and Bangladesh, with 289 and 250 missions respectively (Severino & Ray, 2009, p.6). No less meaningful is the fact that good experiences at the project level do not automatically and necessarily have chain effects on national public policies in beneficiary or partner countries. Many projects with specific objectives fail to converge in the production of a common general objective. When it comes to donors, another issue highlighted by the current literature on “policy coherence for development” deals with negative interdependencies and externalities, for example, between investment and migration policies, development assistance and trade (Barry et al. 2010; Forster and Stokke 1999; Millán Acevedo 2014).

The main message that stems from such a context is clear: there are numerous initiatives and innovations within the scope of international development cooperation agendas, but there are also many frustrated expectations, which, rather than furthering the aims of international solidarity, could lead to a deeper crisis in terms of the political legitimacy of international development cooperation and foreign aid. The general crisis of multilateralism seems to affect the specific context of international cooperation for development. This is not because the OECD’s DAC foreign aid and SSC practices have been implemented mainly through multilateral modalities (Figure 1), along their respective trajectories, but because the “two parallel systems approach” seems to have shortcomings in terms of generating political dialogue and policy initiatives that could be beneficial for development.

IMPLEMENTING SDG#17

With the Covid-19 pandemic, G20 countries face extraordinary and considerable challenges in mobilising and redirecting the much-needed transformative power of reviewing and monitoring frameworks, regulations and incentive structures that should foster private and public investments to reinforce sustainable development. Proposals of a green social agenda to promote sustainable development policies are examples of how some G20 countries attempt to respond to the current critical juncture.

Despite this challenging context, when it comes to the implementation of SDG#17, the situation is much more constructive in terms of information sharing. All G20 members have published reports or made online national information available, providing an overview of their respective domestic implementation efforts to date, stressing areas of progress and those sectors where policy actions need to be taken. In all G20 countries, civil society organisations have published independent reports and participated in monitoring and evaluation activities. Institutionalised participation of civil society, scholars and private-sector organisations through commissions, task forces, consultations or councils exist in almost all G20 countries, except for China, Saudi Arabia and the United States of America. According to the UN 2020 Sustainable Development Goals Report, “support for implementing the SDGs has been steady but fragile, with major and persistent challenges. Financial resources remain scarce, trade tensions have been increasing, and crucial data are still lacking. The Covid-19 pandemic is now threatening past achievements, with trade, foreign direct investment and remittances all projected to decline” (United Nations 2020, p. 58).

Two comments may summarise the reasons for a more conclusive development in this issue-area. First, the UN ensures the general coordination of the 2030 Agenda within the Secretariat, building on previous consensus gained through the UN Millennium Development Goals. Member-states from all regions support the implementation of SDGs and seem to be committed to the 2030 Agenda. Second, states only communicate their respective national strategies to the Secretariat; there are no strategic implications in terms of national interests. Through independent reports, civil society organisations may contest the reality of SDGs, but this policy paper has not engaged with contrasting information coming from independent reports and official documents sent to the UN Secretariat, since these reports are not always easily available. Despite this relatively successful information sharing process concerning SDG#17, G20 countries have not yet succeeded in coordinating their own policies with strategies of other countries across regions. Under SDG#17 there is adequate information from the G20 members on what they are doing at domestic level, but not on their activities outside the domestic sphere. A common framework of action has not emerged either.

DOMESTIC CHALLENGES

International development cooperation and foreign aid are poignant examples of the complexities and dilemmas facing decision-makers in states that seek to signal their ascendance and relevance both regionally and globally. Domestic public opinion, electoral disputes, high unemployment rates, global health crises and environmental threats, among other variables, are relevant to the understanding of States’ decisions in this field. Other challenges may include political turbulence at the national level, the downturn of economic growth rates, corruption scandals concerning relationships between businesses and the public sector, the reduced state capacity to mobilise resources and to implement cooperation projects, as well as the growing drift in some countries towards authoritarian and anti-democratic practices that may hinder social participation, transparency or accountability policies in the field of development cooperation and foreign aid.

For some G20 members, whilst becoming known as an emerging donor in the world of development cooperation could be considered an example of status signalling, at the same time it may involve extra risks. Recognition as a donor could lead to losing or reducing material and symbolic benefits as an official development assistance (ODA) recipient and a peer of other developing countries, even if many “emerging donors” from the South are not OECD members (Westhuizen & Milani 2019). Governments in the Global South may find it difficult to justify their international development cooperation expenses while there are still so many pressing social needs at the domestic level. That may be one of the reasons why Southern countries do not engage seriously and sufficiently with their respective civil-society organisations. Mexico’s SRE has established a department responsible for the promotion of policy dialogue with NGOs and civil society. In Brazil the non-governmental organisation Articulação Sul has created a methodology for data gathering on the country’s development cooperation. Nevertheless, these are still very humble initiatives that do not fully explore the potential contribution of civil-society organisations to monitoring, quantitative evaluation and qualitative assessment of international development cooperation and foreign aid.

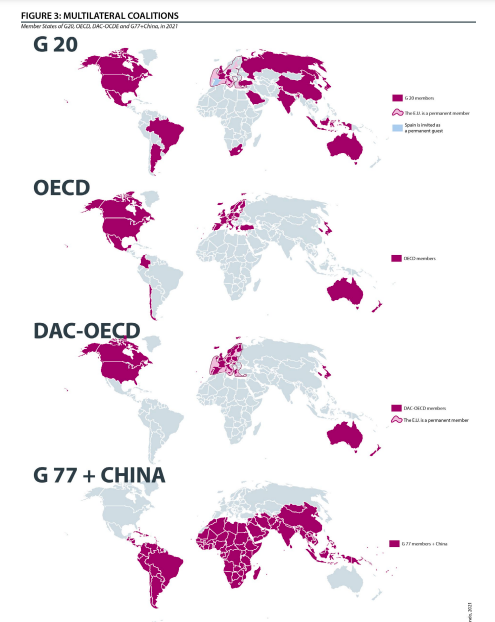

Since March 2020, there is no doubt that the Covid-19 pandemic has been the major challenge that all G20 countries have been confronted with, both internationally and domestically. For G20 countries who are also DAC members (Figure 3), domestic demands for a social and green recovery may bring to the public agenda the need to justify in political terms not only their commitment to multilateralism, but also the maintenance and increase of their foreign aid budgets in response to the needs generated by the global pandemic in the least developed countries. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed astonishing differences in national responses in Europe, North America and Asia, for instance, in terms of social distancing discipline, distribution and use of masks, state capacities to quickly cope with the health emergency, as well as the erratic pace of Covid-19 vaccination across countries. What COVID-19 has exemplarily shown is that local solutions have varied across developed countries. Contrasting experiences largely owing to more comprehensive testing and the earlier imposition of travel restrictions, or to a timely declaration of a state of emergency and the closing down of non-essential public services have produced different effects within and across countries. Even countries with past trajectories of welfare policies and less unequal systems of access to health care have been confronted with difficulties in dealing with the spread of the new coronavirus. They have not been defenceless, when compared to developing countries, but they have been vulnerable to the COVID-19.

In some G20 member-states, furthermore, the rise of anti-science, anti-vaccine leadership has also played a role in the non-delivery of fairer and more effective solutions to the pandemic crisis. Authoritarian nationalisms and key governments North and South of the globe have contributed to new denial campaigns, manufactured uncertainties relating to precautionary health measures and critically for multilateral institutions undermined security recommendations from the World Health Organization.

CONCLUSION REMARKS AND KEY PROPOSALS

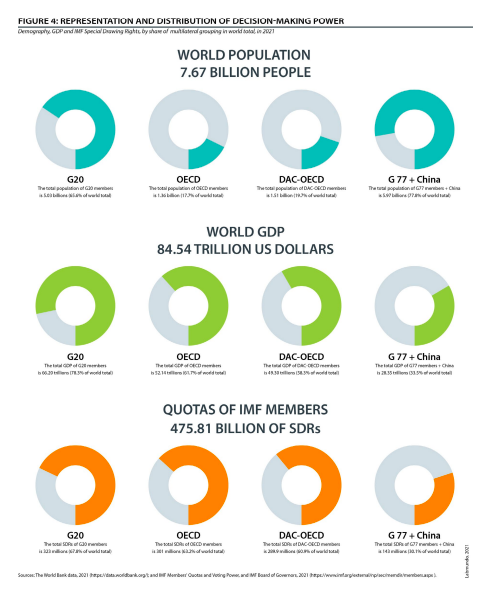

The G20 is neither a universal multilateral organisation nor a homogeneous grouping of states; however, it is politically and strategically among the most relevant platforms in terms of GDP, trade and demography (Figures 3 and 4). Being an informal group may give the G20 some leverage in discussing proposals, in partnership with the UN and the OECD, for a renewed multilateralism in the field of international development cooperation and foreign aid. One of the main challenges relates to the rise of China and other emerging powers, who may bring into the negotiations different systems of values and demands for integrating distinct political principles in the organisation of complex relations between states, societies, markets and nature.

In this rejuvenated multilateralism, there is no doubt that organisations should be more accountable, effective, socially just and environmentally sustainable, starting with the G20. Therefore, we conclude this policy paper with the following recommendation:

- T20 should steer the creation of a Working Group on International Development Cooperation and Foreign Aid (WGIDCFA), wherein Think-Tank representatives (including Think-Tanks from recipient countries), invited agencies (UNOSSC, OECD/DAC, etc.) and scholars could debate on differences and commonalities in statistical definitions of cooperation and aid, norms and criteria, and experiences in monitoring and evaluation, considering the different trajectories G20 countries may have in that regard.

- The WGIDCFA could invite G20 members to send their input, organise policy dialogues around possible frameworks of action in the implementation of SDG#17, build an online platform to gather and disseminate the results of this WG, and identify gaps and duplications.

- The WGIDCFA could delve into options to strengthen development cooperation and aid data, thus ensuring there is value addition to the already existing OECD-DAC members’ platforms for dissemination. Further, non-DAC and non-G20 members could also be invited to exchange views with the Working Group.

- Because SSC members tend to use the UN Development Cooperation Forum, which generally reports on trends without a clear tool for monitoring, evaluation and assessment, the WGIDCFA could explore available opportunities under the UN to strengthen such engagement.

- Within the T20, CEBRI could volunteer to participate in the WGIDCFA, if possible as Chair or Co-chair.

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

Barry F., M. King, and A. Matthews, Policy Coherence for Development: Five Challenges, Irish Studies in International Affairs, no. 21, 2010, p. 18

Besada H. and S. Kindornay (eds), Multilateral Development Cooperation in a Changing Global Order, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013

Development Initiatives, Investments To End Poverty 2013, Real Money, Real Choices, Real Lives, Bristol, Development Initiatives, 2013

Development Initiatives, 2020 Progress Report, 2020 https://devinit.org/Resources/Dis-Progress-Report-2020/#Downloads.

Develtere P., H. Huyse, and J. Van Ongevalle, International Development Cooperation Today, A Radical Shift Towards A Global Paradigm, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2021

Forster J. and O. Stokke, Policy Coherence In Development Cooperation, New York, Routledge (EADI Book Series 22), 1999

International Development Association (IDA), Aid Architecture: An Overview Of The Main Trends In Official Development Assistance, Washington, IDA/The World Bank, 2007

Kharas H., “Can Aid Catalyze Development?”, in Making Development Aid More Effective, Washington DC, The Brookings Institute, 2010, pp. 3-9.

Klein M. and T. Harford, The Market for Aid, Washington DC, The International Finance Corporation, The World Bank Press, 2005

Lancaster C., Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2007

Mavrotas G. and P. Nunnenkamp, “Foreign Aid Heterogeneity: Issues And Agenda”, Review of World Economics, vol. 143, no. 4, 2007, pp. 585-95

Milani C.R.S., “Covid-19 Between Global Human Security And Ramping Authoritarian Nationalisms”, Geopolítica(S). Revista De Estudios Sobre Espacio Y Poder, vol. 11 (Special Issue), 2020, pp.141-51

Millán Acevedo N., Reflexiones Para El Estudio De La Coherencia De Políticas Para El Desarrollo Y Sus Principales Dimensiones, Madrid, Papeles 205 Y Mas N. 17, 2014

OECD, Development Co-Operation Report 2020, Paris, OECD, 2020

Purushothaman C., Emerging Powers, Development Cooperation and South-South Relations, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2020

Severino J.-M. and O. Ray, The End of ODA: Death and Birth of a Global Public Policy, Working Paper Series, Center for Global Development (Www.Cgdev.Org), no. 167, 2009

United Nations, The Sustainable Development Goals Report, New York, The United Nations, 2020 https://unstats.un.org/Sdgs/Report/2020

Westhuizen Van Der J. and C.R.S. Milani, “Development Cooperation, the International-Domestic Nexus and the Graduation Dilemma: Comparing South Africa and Brazil”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 32, no.1, 2019, pp. 22-42