In December 2018, G20 leaders committed themselves to fair and sustainable development, focusing, among other issues, on the labour conditions in global production networks. These G20 commitments, in themselves, do not offer a roadmap for implementation. In this policy brief, we contribute towards such a roadmap, by showing how responsible production in global value chains (GVCs) represents a promising vehicle for achieving a fair and sustainable workplace. This policy brief argues that, in the world of complex GVCs, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a potential tool for firms to respond to stakeholder pressure and for governments to put firms in charge of responsible production.

Challenge

On 1st December 2018, at the G20 meeting in Buenos Aires, G20 leaders committed themselves to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8), which includes the right of decent work conditions for all. Specifically, SDG 8 aims to reduce workplace accidents, to recognise international labour rights and to eliminate child labour. This was a reiteration of the commitment in the German G20 Communique a year before, in which leaders also declared to work towards adequate national policies and underlined the responsibility of businesses to cooperate in these efforts.

But the realities of the present workplace makes it difficult for G20 leaders to deliver this commitment. One of these realities, is the complexity of global value chains (GVCs). To illustrate the consequences of these complexities for labour rights, we refer to the severe shortcomings in the global response to the Rana Plaza accident (collapse of textile factories in 2013 with loss of 1,134 lives).

Without any doubt, G20 governments should do everything conceivable to prevent such an event from happening, but if we take a look at GVCs nowadays, we are presented with a set of enormous challenges –

- Complex/long production chains: It gets increasingly challenging for firms and their stakeholders to monitor the sustainability of GVCs.

- Conflicting stakeholder expectations: Diverging expectations of a firm’s consumers, civil society and policy makers can discourage responsible firms, can be exploited by opportunistic firms and can limit the scope for government policy design.

- Offshoring of production stages by Multinational Enterprises (MNEs): Goods and services produced at a remove from the MNE’s country of origin can shift the real burden of cheap production to producer countries (e.g. shoddy work practices), enabled by differing priorities of home and host country policy makers.

- Not all firms are alike: Differences in firms’ visibility, scale and nature of operation – such as proximity to the end-consumer or the sectors – lead to different levels of transparency in how sustainably firms produce goods and services.

- Growing public scepticism: The ability of firms to ensure responsible production along their entire value chain has become subjected to increasingly intense public scrutiny.

We have outlined main challenges confronting policy makers attempting to ensure that goods and services get produced worldwide safely, ethically and in a sustainable way.

All in all, policy makers walk a dizzy tightrope – desiring to remain pro-business while also desiring positive social outcomes from globalised firms. Can this tightrope be walked?

We turn the spotlight on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), a promising tool to help G20 governments and businesses to shape the Future of Work. There is no clear-cut definition which firms’ activities can be described as CSR. On the one hand, McWilliams and Siegel (2001) define it as “actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law”. Others summarise CSR as a firm’s investment in order to conform to ethical production standards set by its stakeholders (e.g. Locke, Amanguel, Mangla, 2009; Park, Chidlow, Choi, 2014; Zheng, Luo, Maksimov, 2015). All in all, CSR offers firms an instrument to serve the wider society, to freely demonstrate their goodwill while avoiding binding legislation.

Evidence-based research on the impacts of CSR is emerging and helps us to shed light on the issue of sustainability in GVCs, pointing us towards recommendations to create better outcomes for consumers, workers, and businesses. Previous studies suggest that CSR engaged firms are also more effective in achieving a fair and sustainable workplace. But in its current form, CSR is often not fit for purpose. The Future of Work necessitates a fresh approach to CSR, a realignment of how CSR is conceived, a version of CSR that improves labour outcomes along the entire value chain of the firm.

First, we argue that policy makers should be able to identify ‘honest’ CSR. Second, we encourage any measures that independently and transparently evaluate the extent of a firm’s commitment to socially responsible production. Third, we advocate a multilateral approach towards CSR in both harmonising reporting standards and, if necessary, in coordinating legislation. Lastly, we emphasise the importance for firms and the society of stakeholders to support supplier development within GVCs.

Proposal

Proposal 1: Promote ‘honest’ CSR

Firms can engage in ‘greenwashing’, where a firm masquerades as being environmentally friendly or socially responsible (e.g. using deceptive labelling). Greenwashing helps firms to deflect criticism from Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) or other interest groups.

Moreover, ‘legal compliance’ is often (disingenuously) mislabelled as CSR. But compliance neither meets the CSR-definition by McWilliams and Siegel (2001) nor is it a substitute for CSR. Firms that meet minimum compliance standards, may yet fail to act responsibly, e.g. the 2012 factory blaze claiming nearly 300 lives in the Ali garment factory in Pakistan. Fire exits were blocked despite the factory having recently secured its SA8000 label in compliance with international labour standards (AFL-CIO, 2013).

We recommend that policy makers and especially G20 policy makers work towards designing and implementing mechanisms that help identify and reward firms conducting ‘honest’ CSR – those meeting minimum standards under legislation and exceeding these standards by their CSR engagement.

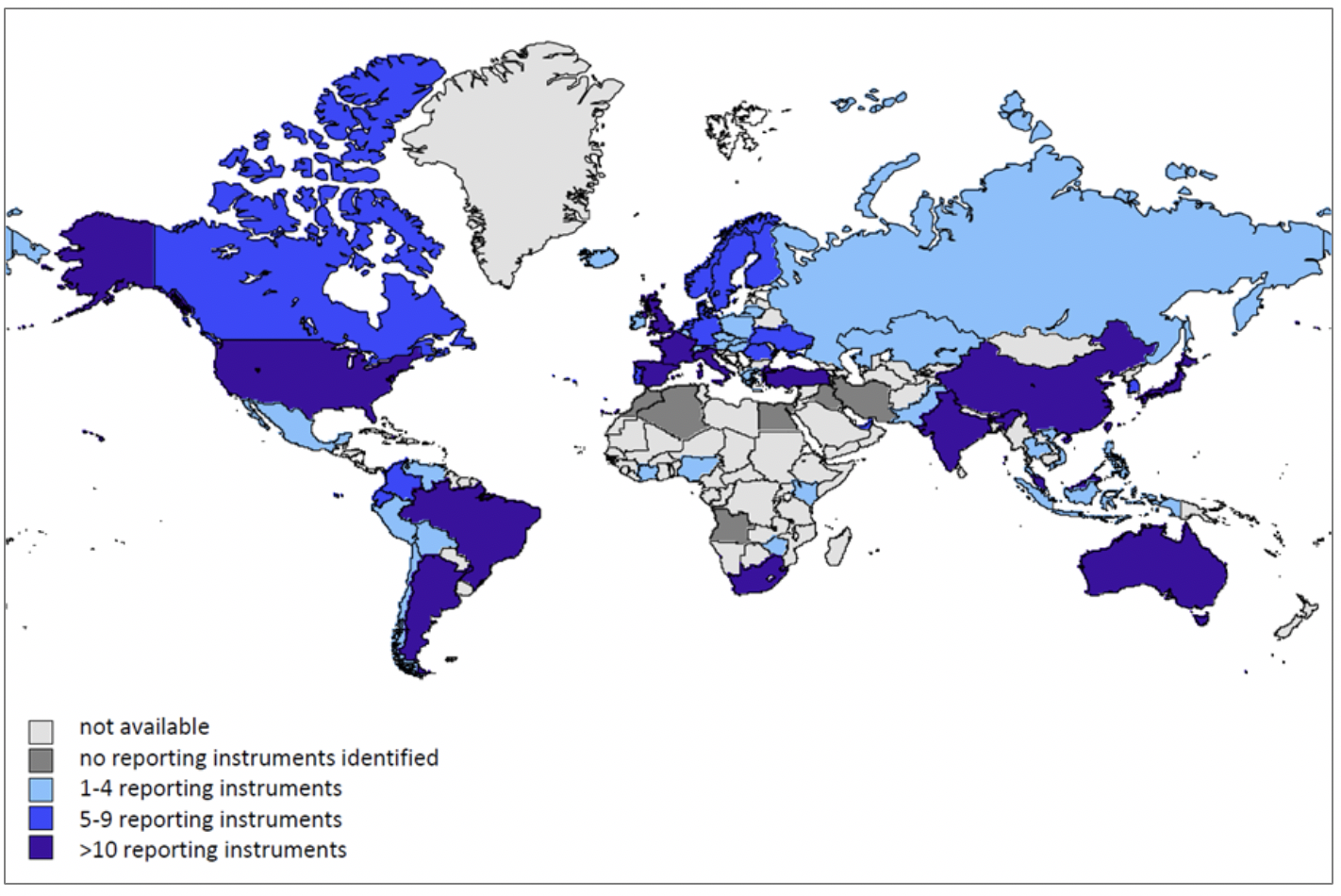

We welcome the fact that public awareness of CSR has continued to rise, as suggested by a rise in the number of reporting instruments (cf. Figure 1). An example of a recent reporting instrument is the EU directive on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information, which targets a firm’s sustainability. This directive obliges firms to apply a wider set of criteria in their disclosure statements and to apply principles set down by a wider set of international bodies (e.g. standards set by the NGO ‘Global Reporting Initiative’). However, this instrument applies only to large – and as such highly visible – firms (Bartels et al., 2016). Arguably, a comprehensive approach towards CSR along the entire value chain involves the activities of smaller firms too. Indeed some smaller firms can signal their CSR engagement and might capitalise their good-will. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the administrative burdens of a detailed reporting and turn to the inclusion of small and medium sized suppliers in a comprehensive CSR strategy in our last proposal.

Figure 1: Number of reporting instruments per country

Source: Own visualisation based on data from Bartels et al. (2016)

Proposal 2: Ensure an assessment mechanism of firms’ CSR impact

To reveal the true impact of firms’ CSR engagement, it is essential to set up an independent and transparent assessment mechanism. We acknowledge that the evaluation of the true impact on the social status quo is a challenging task for both governments and researchers. However, to avoid the risk of corporate hypocrisy, the impact of CSR needs to be measurable.

Due to a lack of proper CSR data, researchers usually capture CSR via different dimensions that are associated with socially responsible behaviour: wages, compliance with labour and environmental standards, established CSR strategies at the management level, or community related engagement. Görg, Hanley, and Seric (2018) find that CSR-active MNEs report significantly higher worker wages in 19 Sub-Saharan African countries. Additionally, local African suppliers benefit from CSR through knowledge transfer, but only when MNEs make tangible investments in supplier development. The result indicates improved outcomes for workers of globally active firms.

Newman et al. (2018) look at the CSR engagement of Vietnamese firms and find that exporters are more committed to CSR compared to firms only serving the domestic market. Moreover, they reveal an important channel for increased CSR engagement in GVCs. If a firm starts to export, its stakeholder composition changes to include foreign stakeholders such as foreign consumers, buyers of intermediates and governments. Accordingly, they find that a firm’s export activity increases CSR engagement, if the US market is served. No such pattern is visible for exports serving China. In line with this, Görg et al. (2017) have found robust evidence that CSR matters more for firms that export to developed countries.

The findings of these studies testify to the positive effects of CSR on working conditions and the society. Nevertheless, more evidence is crucial for decision making. Accordingly, we claim that setting up an independent and transparent assessment mechanism, which enables an evaluation of firms’ socially responsible production, is required as an effective tool to promote sustainable development.

This evaluation itself has to be transparent and independent to enable stakeholder a comprehensive judgement – whether minimum standards are met and CSR engagement has a positive impact or not. When drafting a catalogue of CSR best-practice, policy makers can draw on criteria from existing frameworks such as the United Nations SDG 8, OECD Guidelines for MNEs from 2011, the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights by the United Nations implemented in 2011 and the MNE Declaration of the International Labour Organisation (most recently revised in 2017).

Proposal 3: Promote socially responsible production and reporting harmonization in multilateral forums

The worldwide increase of CSR-reporting instruments calls for increased harmonization. Alignment and harmonization must be a key goal for all stakeholders to reduce the reporting burden on enterprises (Bartels et al., 2016). On the one hand, common reporting standards improve the possibilities for an independent assessment of the social impacts of CSR in GVCs. On the other hand, such harmonization is only possible if countries achieve consensus in multilateral forums. The G20 represents an unique forum to pave the way for harmonization of reporting standards across the world.

Multilateral agreements are also key to preventing that countries adopting CSR standards are being placed at a competitive disadvantage. Achieving multilateral consensus is of course not easy. The slowness of multilateral decision-finding or even its downright failure to achieve a consensus, is however no licence for any individual government not to implement its own rules on sustainable production. National governments have the obligation to do everything possible to ensure that domestic firms and MNEs produce in accordance with basic human rights, social, and environmental global standards. This obligation neither waits for multilateral agreements, nor ends at the national border. Accordingly, this obligation is valid along the entire value chain.

In our prior proposal, we claim for setting up an independent and transparent assessment mechanism of a firm’s socially responsible production. Since not all firms meet even minimum standards, we recommend individual governments to specify a fixed deadline by which minimum standards have to be reached on a voluntary basis. Governments should credibly communicate that the alternative to a voluntary approach is a legally binding approach. Once minimum standards are met nationally, policy maker should aim for multilateral harmonization to promote CSR engagement beyond the minimum standards required by compliance.

Proposal 4: Facilitate inclusion of small and medium sized suppliers

As mentioned earlier, existing reporting initiatives widely fail to capture the activities of smaller firms. Accordingly, the activities of small firms frequently pass beneath the radar. We are fully aware (and endorse) the view of policy makers not to increase the administrative burden on small and medium sized firms, beyond what is reasonable. Nonetheless, we claim that these small firms represent an important component in the overall plan for a comprehensive CSR strategy. In the light of long and complex value chains, the integration of all parties of a chain becomes crucial. A chain is, after all, no stronger than its weakest link.

Successful implementation of CSR along the value chain hinges on the question of whether all firms involved – especially small and medium sized suppliers or those in less developed countries – are able to meet requirements, adopt standards, or obtain certificates. At the same time, not only have smaller firms a reduced capability of adopting CSR standards beyond the minimum standards required for compliance (certification is expensive), but also small firms have a reduced incentive to invest in cleaner or fairer production processes if they cannot capitalise their social engagement. Evidence shows that assistance provided to local suppliers is crucial for suppliers’ innovation activity and productivity (Görg & Seric, 2016). Many large firms – especially MNEs – already have their own supplier development strategies and departments that assist their suppliers in attaining the respective requirements. Additionally, the involvement of governments and international organizations is of key importance for this strategy to work, e.g. to help provide financial assistance and training (e-learning) programmes for both actual and potential suppliers. We recommend that the existing tools, assistance programs, and information are packaged and promoted more intensively. Once again policy makers can draw on already existing platforms (like SEDEX). Platforms that consolidate information facilitate the inclusion of small firms and can help to reduce the barriers that prevent them from entering GVCs.

References

AFL-CIO (2013). Responsibility outsourced: social audits, workplace certification and twenty years of failure to protect workers’ rights. AFL-CIO, Washington D.C.

Bartels, W.; Fogelberg, T.; Hoballah, A. & van der Lugt, C. (2016). Carrots and Sticks – Global trends in sustainability reporting regulation and policy.

Görg, H.; Hanley, A. & Seric, A. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains: Deeds not words. Sustainability, 10. 3675.

Görg, H.; Hanley, A.; Hoffmann, S. & Seric, A. (2017). When do multinational companies consider corporate social responsibility? A multi-country study in Sub-Saharan Afria, Business and Society Review, 122, 2, 191-220.

Görg, H.; Seric, A. (2016). Linkages with multinationals and domestic firm performance: The role of assistance for local firms, The European Journal of Development Research, 28, 4, 605-624.

Locke, R.M.; Amanguel, M.; Mangla, A. (2009). Virtue out of necessity: Compliance, commitment, and the improvement of labor standards. Politics & Society, 37, 319-351.

McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective, Academy of Management Review, 26, 117-127.

Newman, C.; Rand, J.; Tarp, F. & Trifkovic, N. (2018). The transmission of socially responsible behaviour through international trade. European Economic Review, 101, 250-267.

Park, B.; Chidlow, A.; Choi, J. (2014). Corporate social responsibility: Stakeholder influence on MNEs’ activities. International Business Review, 23, 966-980.

Zheng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Maksimov, V. (2015). Achieving legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: The case of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 50, 389-403.