Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) generally suffers from low status and is regarded as inferior to academic study. Moreover, TVET institutions, which were established to be authoritative in knowledge and skills, need to adapt to an environment where the knowledge flow is reversed, with skills increasingly being generated within economic activities. Technology is also changing the kind of skills required by employers. A new relationship between educator and employer must be established for effective, high profile TVET and workbased learning programs. We propose a B20-L20-T20 collaboration and a G20 database on TVET to promote best practices.

Challenge

Our world of work is going through a rapid transformation. Globalization, demographic shifts (aging in advanced economies alongside growing youth bulges in South Asia, Middle East, and Africa) and technological changes brought about the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) (Schwab, 2016) are having profound effects on the global labor market. These disruptions raise issues around the types of skills and learning required for the future of work.

Technology is changing the skills requirements of occupations, affecting both new entrants to the labor market and older workers. Unfortunately, current education systems are not adequately preparing the workforce for these changes, tending to fail both young and old. There is a disconnect both in terms of curriculums and requisite skills in occupations and between education outcomes and employers’ needs.

Globally, many youths are unemployed or disengaged from the labor market. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 64 million youth are unemployed worldwide (ILO, 2019). More strikingly, 20 percent of young people are not in education, training or employment—they are disengaged. At the same time, millions of jobs remain unfilled. In part, this is brought about by youth not possessing relevant work experience, having underdeveloped or inadequate skills, and lacking career guidance. A 2013 McKinsey study reported that 39 percent of employers surveyed cited skills shortage as the main driver for the vacancies (Barton, Farrel, and Mourshed, 2013). This paradox—high youth unemployment alongside widespread vacancies— requires rethinking the role that education systems, and specifically TVET and other types of work-based learning, can play in bridging this divide.

Sadly, there is a residual view in most countries that an academic track is the only pathway to a good career, while TVET—in both traditional occupations (i.e., construction and manufacturing) and emerging occupations (i.e., Information technology, hospitality, and management) remains stigmatized as inferior. Yet TVET graduates with the requisite knowledge and skills can command high salaries, particularly in advanced economies, a fact that is given insufficient emphasis when advising young people about their career possibilities (BLS, 2019, OECD, 2018a). These salaries are far higher than TVET institutions can pay their instructors, causing a potential shortfall in teachers. One solution would be to create mechanisms and systems whereby highly skilled employees can contribute to the learning process, benefitting not only TVET institutions but also creating opportunities for TVET innovations. Such partnerships could represent two-way flows—from workplaces into educational settings and through joint working for knowledge and skills to flow back into workplaces. Such a two-way street could both help raise the standing of TVET systems and the quality of work-based learning.

Given this confluence of challenges, the G20 could have an important role in examining pathways to employment and the role that TVET can play both for those entering workforce and older workers that need to reskill. TVET systems must increase their partnership with employers to ensure appropriate forms of learning and access to world-class skills to promote new and continuing employment suitable for a high-skill economy and newly emerging forms of employment. The G20 can be instrumental in this regard.

Proposal

Promoting Best Practices on TVET across G20 Countries by Understanding the Actual Situation of Self-Employed Individuals Working via Platforms

This proposal is for two interconnected policy actions.

• Policy Action 1: The first is that the G20 establish a T20-B20-L20 collaboration to promote TVET and work-based learning within the G20. This group could collaborate with networks such as UNESCO-UNEVOC, the Global Apprenticeship Network (GAN) and the European Apprenticeship Network to increase understanding of the nature of TVET learning and share best practices of TVET within G20 countries.

• Policy Action 2: To support and empower the group established under Action 1, a second policy action is needed to create a G20 database or tool to promote and inform about TVET requirements and labor market outcomes. This database could complement other efforts, for example, the OECD Skills for Jobs database (2019), with a greater focus on future looking trends in employment. It would:

- examine labor market outcomes of general education, TVET and academic university provision;

- explore the education and skills requirements for different occupations; and

- calculate comparative cost/benefit of academic education versus TVET.

Policy Action 1: T20-B20-L20 Collaboration to Promote TVET and Work-Based Learning within the G20

The B20 has recently noted (B20, 2018) “Employability has to be a key component of education systems in order to avoid skills mismatches on the labor market. In this sense, close cooperation between businesses and relevant government agencies and institutions is key to ensure that the curricula of training systems are in line with labor market needs.” In this regard, TVET and other types of work-based learning can be pivotal to close this gap.

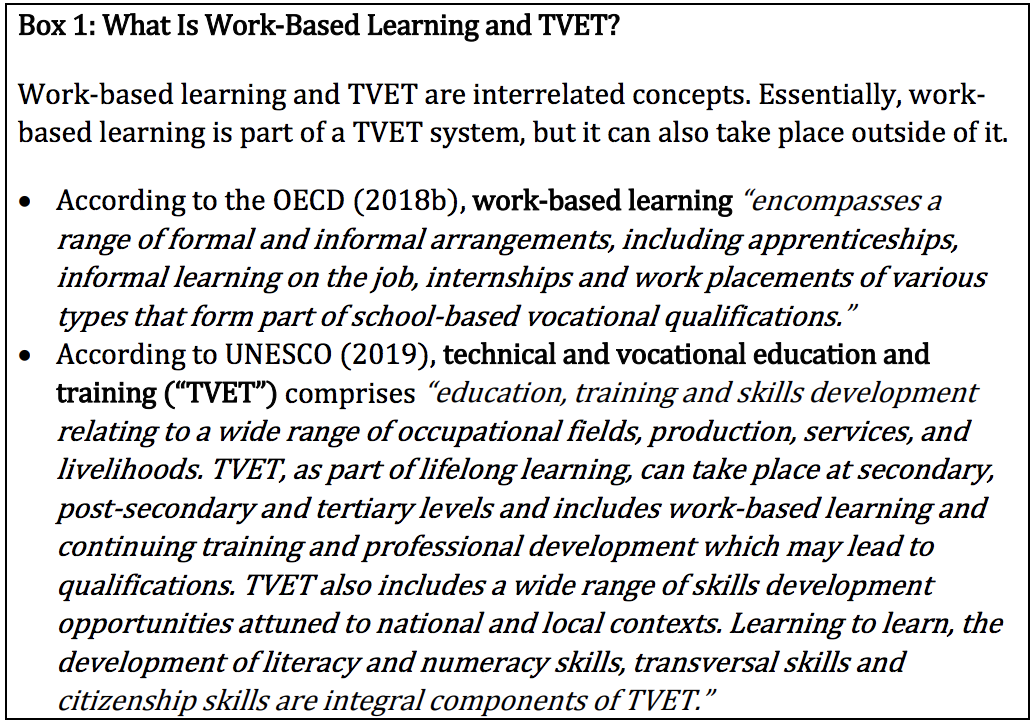

Promoting work-based learning and TVET can be effective in easing the school-to-work transition and providing young people with skills that more closely aligned to employers’ needs (Box 1). As the OECD (2018b) and UNESCO (2016) note, work-based learning is an avenue to reskill vulnerable groups and upskill older workers, but it is vital that it is not restricted to, or identified with, under-performing groups. Work-based learning is important not only for manual or low-skilled occupations but plays a significant role in the new middle- and high-level skilled occupations.

In general, from the upper secondary phase onward technical instruction of some kind, or TVET, has been introduced in most G20 countries with a view to enhancing employment potential. However, across these nations, there is no consensus as to the nature of TVET, its structure, content, or the type of institutions in which it is delivered. Far too often TVET appears only within organizations characterized as low status or remedial.

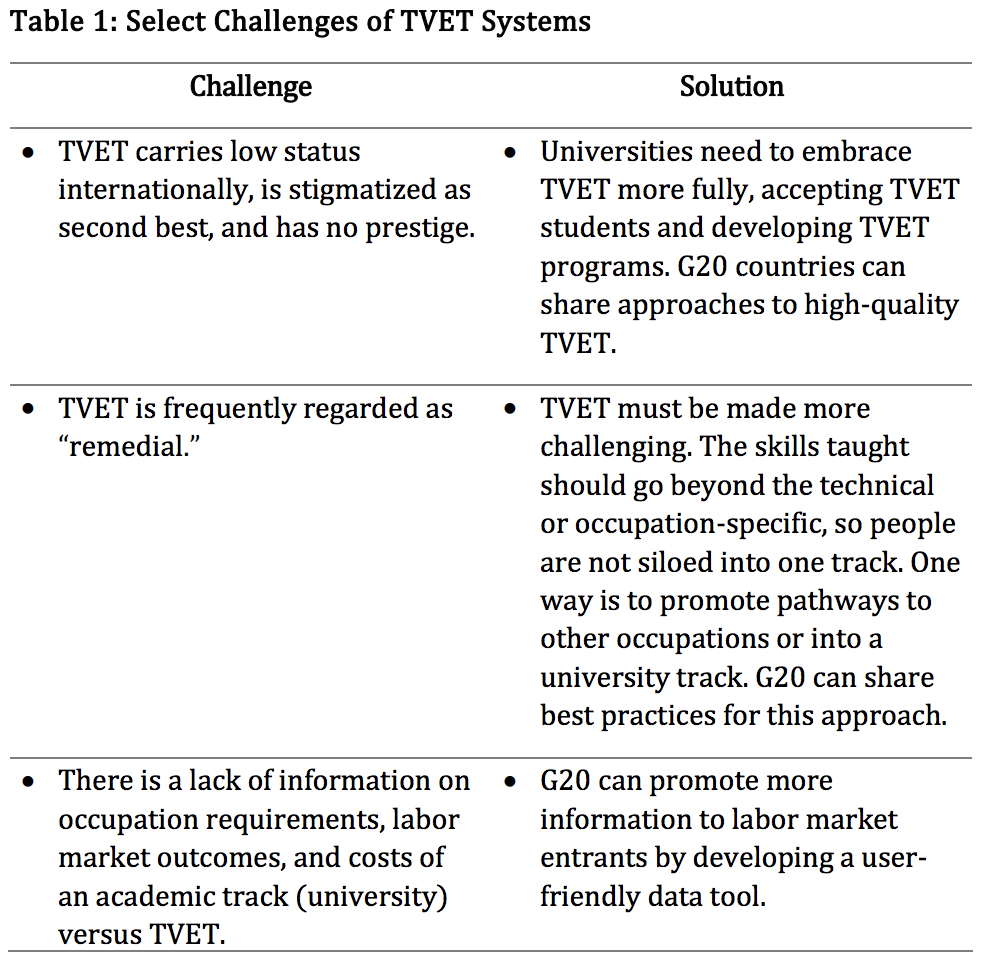

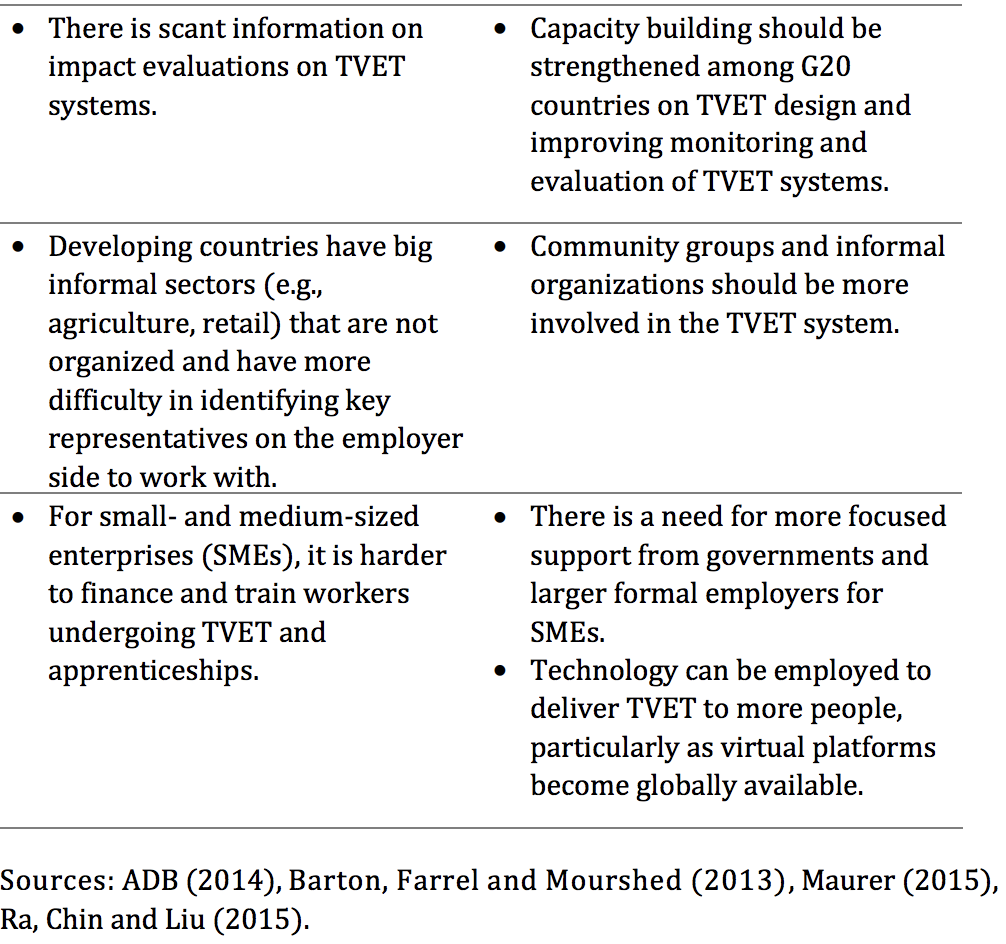

The first strand of this proposal is important because too many policymakers and other stakeholders do not fully understand the nature of vocational learning. There is a fundamental difference in how learning takes place in an academic setting and the style of learning that underpins high-quality vocational training, which is driven to supply practical and job-specific skills. Too often, TVET systems are supply driven, that is, they are dictated by government officials’ understanding of the labor market instead of relying on private sector demands. Linking the business sector in TVET is crucial. Another challenge is that policymakers and other stakeholders view TVET as a second-best choice to a university degree or as a remedial intervention for vulnerable groups or dropouts. A T20-B20-L20 collaboration can overcome some of these barriers by bringing in the business community and showcasing best practices in TVET that countries can emulate (Table 1). Furthermore, evaluations of TVET systems are scant. G20 countries need to build more capacity in monitoring and evaluation of TVET systems. The results of such evaluations will help us understand what works and can inform TVET design.

Recent studies are quite clear that good TVET takes a new approach to learning whereby the “relationship between theory and practice is inverted in technical education when compared to academic study, with practice necessarily preceding theory.” (Doel, forthcoming) This “Learning by doing” is accompanied by a wholly different approach to assessment, which is ongoing and therefore impacts the way that learners are profiled and certificated. When creating a garment, for example, there are no correct answers. Provided certain fundamentals are met, the garment is evaluated according to a whole range of criteria: practicality, fashion, culture, warmth, durability, cost, etc. This is a continuous process of evaluation whereby the garment, or any artifact or service is reviewed and modified during the process of the design phase, and improvements introduced.

A further condition of excellent TVET is the need for a clear line of sight between the learning environment and the work environment (CAVTL, 2013). This line of sight was most likely to be engendered by a two-way street of continuous engagement between the education institution (and its teachers) and the industries in which students are being prepared for employment. Furthermore, teaching is more effective when delivered by dual professionals—those highly skilled in both their employment domain and in the art of teaching. Some ways that employers and educators can be brought together are through the secondment of teachers into employment, providing financial incentives to those working in industry to lure them into teaching, setting up apprenticeships or other forms of work-based learning and designing strategic partnerships between education institutions and employers to share staff and resources.

With under-developed TVET systems, many countries will face significant challenges in designing, financing, and implementing new forms of workbased learning. The G20 could have a significant impact in disseminating the distinctive features of high-quality TVET amongst its members and promoting good practices, particularly to overcome the bias that “vocational” learning is remedial or of low status. Across G20 countries, there is a need to understand the challenges and opportunities of different TVET systems (and other forms of work-based learning) and to learn about best practices to overcome those challenges. A joint T20-B20- L20 partnership could lead this effort.

Policy Action 2: A G20 TVET Database or Tool to Help Inform on TVET Requirements and Labor Market Outcomes

The second strand of this proposal is the creation of a G20 tool on TVET that can provide more tangible information on the skills requirements for each occupation, costs of education, and labor markets outcomes on TVET across countries. Governments, educational institutions, and citizens need to understand that technological shifts are impacting how people learn, what skills will be required in each occupation, the costs to acquire such skills, and what labor outcomes one can expect (e.g., vacancies, wages, job characteristics). Currently, this information is not readily accessible to many. As mentioned, sharing more information across G20 countries on TVET and other forms of work-based learning can help inform good TVET design across governments and support citizens as they consider different careers if they are given relevant data. Policy Action 2 complements and supports Policy Action 1 in the sharing of knowledge and best practices of TVET across G20 countries.

The economic shifts brought about by the 4IR will have implications on employment and the type of skills required for the digital age. The 4IR will bring new ways of working, such as the “platform economy,” and will create new jobs, as economies respond to the impact of developing technologies (Evans and Schmalensee, 2016). The evolution of new forms of work is likely to accelerate, but not uniformly. The relationship between technological innovations and their implications for the future organization of work and demand for skills cannot be reduced to the view that automation and robotization are inevitable and human work will be replaced by technology (Autor, 2015). New technologies can result in the creation of new jobs and new skills, but many cannot be predicted yet.

What is observable in contemporary economies is first and foremost the need to revisit skills: the skills that were underpinned by a single qualification are no longer sufficient. Moreover, employees do not have to gather together to be productive. Factories can be replaced by smaller units; an individual can have a global reach once they have access to the internet. Both smaller units of production and extended reach require enhanced networking skills, such as well-developed interpersonal skills that are effective over a virtual medium. Barber (2016) argues that vocational learning will become much more collaborative as students debate and elaborate each other’s ideas in online environments. As routine cognitive tasks are increasingly automated, it is the qualities that make us distinctively human—empathy, storytelling, and connecting— that will be in ever greater demand. Colvin (2014) suggests that graduates of the future might be better off studying literature and so developing skills such as reading, social nuance, and understanding someone else’s perspective. There is thus a need for a wholesale reconsideration of the design of TVET courses, supported by evidence from the proposed G20 collaboration.

Historically, it has been the case that the different ways of working coexist alongside, rather than replace, one another. Not everyone will be an artificial intelligence (AI) specialist but can become adequately competent to be able to use and apply the technologies critically. Employees will need to feel comfortable working in AI environments supporting a continuing role for creative human intervention, rather than “technological scientists.” A well-designed TVET system should therefore both promote social skills and high-level technical skills. The types of skills taught in vocational training need to broaden: from narrow technical skills associated to a specific occupation to a wider set, such as socioeconomic skills that can prepare workers to navigate an everchanging labor market (OECD, 2018b; Barber, Fernadez-Coto and Ripani, 2016). Communication between employers and TVET providers needs to be enhanced to ensure the supply of such skills.

TVET should move beyond its “modernist” industrial image and in the future support interaction and creativity which can be assistive to the digital world. In this way, advanced TVET might come to assert a status equivalent to the highest levels of academic study. TVET systems therefore need to be flexible and adaptive to the new labor environment. The G20 could play a pivotal role in identifying and disseminating examples of high quality, forward-thinking TVET. In this regard, a G20 database (or tool) that can provide information on skills, cost of education and outcomes of TVET, and other learning paths can be useful not only for G20 policymakers but for educators, employers, and families as they then embark on the complex but fascinating journey to employment.

Conclusion

Education systems are not adequately preparing the workforce for the current demands of the labor market. Strong population growth in developing countries will bring added pressures to supply schooling and decent jobs for millions of new entrants. The UN predicts that there will be 3.3 billion people under the age of 25 by 2030, most living in Asia and Africa. Africa will double its population by 2050 and 60 percent of its citizens will be under the age of 25 (UN DESA, 2017). This represents a demographic opportunity that could be wasted if economies do not create meaningful jobs and educate new generations appropriately for the future of work (Bandura and Hammond, 2018). In this regard, TVET should not be overlooked as a legitimate pathway to employment. The G20 cannot pass up on this opportunity to influence the global education agenda and promote strong TVET systems within and across its members. This will require building strong coalitions among governments, the business community, and education institutions.

References

• Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2014). Sustainable Vocational Training Toward Industrial Upgrading and Economic Transformation A Knowledge Sharing Experience.

• Autor, David H. (2015). “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Summer 2015, 29(3), 3-30.

• Bandura, Romina and MacKenzie Hammond (2018). “The Future of Global Stability: The World of Work in Developing Countries”. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

• B20 (2018). Employment and Education Taskforce. https://www.b20argentina.info/TaskForce/TaskForceDetail?taskForceId=43409f0 b-0e10-4e79-844a-a1209e0516e3

• Barber, Michael (2016), “What if further education and skills led the way in integrating artificial intelligence into learning environments?”, In Possibility Thinking: Creative Conversations on the Future of FE and Skills. https://fetl.org.uk/publications/possibility-thinking-reimagining-the-future-offurther-education-and-skills/ Accessed 11/2/2019)

• Barton, Dominic, Diana Farrell, and Mona Mourshed (2013). “Education to Employment: Designing a System that Works”. McKinsey Center for Government

• Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2019). “O’Net Online”. https://www.onetonline.org/ • Colvin, Geoff. (2014). “In the future, will there be any work left for people to do?” Fortune, June 16.

• Commission on Adult Vocational Education Teaching and Learning (CAVTL) (2013), “It’s About Work”. Available at: https://www.excellencegateway.org.uk/content/eg5937.

• Evans, D. S. and Richard Schmalensee (2016), “Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms.” Harvard Business Review Press.

• Fazio, M. V., Raquel Fernández-Coto, and Laura Ripani (2016), “Appenticeships for the XXI Century: A Model for Latin America and the Caribbean?”, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

• Doel, M (2018) “Technical Education: A Defining Role for Colleges in New Frontiers for College Education”: International Perspectives: Gallacher and Reeve Routledge

• Grainger, Paul and Ken Spours (2018), “A Social Ecosystem Model: A New Paradigm for Skills Development?”, Available at: https://t20argentina.org/publicacion/asocial-ecosystem-model-a-new-paradigm-for-skills-development/.

• International Labor Organization (ILO). 2019. “Youth Employment”. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/youth-employment/lang–en/index.htm

• Isaacs, Tina, Brian Creese, Alvaro Gonzalez (2015). Aligned instructional systems: Cross-jurisdiction benchmarking, report. Center for International Education Benchmarking (CIEB). Retrieved from: https://www.ncee.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/09/AIS-Cross-Jurisdiction-Report.pdf.

• Maurer, Markus. (2015). “The Role of the Private Sector in Vocational Skills Development”. Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC.

• OECD (2018a). “The Role of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Fostering Inclusive Growth at The Local Level in Southeast Asia”. Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5afe6416- en.pdf?expires=1553525483&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=71BC0EAFBA79 901685F7A3CB8F95C132

• OECD (2018b), “Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience”, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris.

• OECD (2019), OECD Skills for Jobs (database).

• Ra, Sungsup, Brian Chin and Amy Liu. (2015). (2015). Challenges and Opportunities or Skills Development in Asia: Changing Supply, Demand and mismatches. Asian Development Bank (ADB)

• Schwab, Klaus (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum.

• UNDESA (2017), 2017 Revision of World Population Prospects (database).

• UNESCO (2016), “Strategy for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) (2016-2021).” Paris.

• UNESCO (2019), TVETipedia Glossary, Available at: https://unevoc.unesco.org/go.php?q=TVETipedia+Glossary+AZ&term=Technical+and+vocational+education+and+training.