You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Youtube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

Severe recessions and financial crises are frequent. Their effect on the economy is persistent and often exceeds initial projections. They can also be a strong driver of widening inequality. Therefore it is important that measures be taken to minimise the risk of such events while strengthening the potential for economies to innovate and prosper (Phelps, 2013). An economy’s resilience to crises and recessions can also be strengthened. Minimising risks requires the accurate monitoring of home-grown vulnerabilities in real-time; coping with the consequences means identifying and putting in place policy settings and mechanisms that can help absorb the impact of a severe downturn and facilitate a swift rebound of economic activity. Strengthening resilience will also provide a key contribution to solving the global problems of rising populism, nationalism and protectionism.

Challenge

The post-war record of severe recessions and financial crises offers several lessons for how economic resilience can be strengthened. Major global crises such as the 2008-09 episode are rare, but severe recessions have been quite frequent over the past 40 years. Over 1970-2010, 120 episodes of banking, currency or sovereign debt crises have been recorded across a sample of advanced and major emerging market economies.[i] During the same period, over 100 severe recessions have been recorded. Severe recessions are referred to as episodes when GDP falls by more than 3½ per cent from peak to trough. The last major episode has shown that, in periods of relative stability in terms of growth and consumer price inflation, growing risks and vulnerabilities are easily overlooked. Across advanced economies, there are signs that appetite for innovation-based prosperity is weakening (Phelps, 2013).[ii]

Furthermore, recent political developments have also shown that the growing discontent in advanced economies about the distribution of growth dividends has been underestimated. These long-term distributional consequences have had an impact on the economic resilience of households and often imposed adjustment costs on marginal workers. The discontent this has engendered and the perceived divide between the elites and the public can result in populist economic responses that increase barriers to trade and more generally make economies more closed. Yet, with the rise in inequality in advanced economies stemming mostly from technological progress, protectionist policy responses risk hampering growth without reducing inequality.

What can policy makers do to lastingly enhance resilience in the face of economic and financial risks to safeguard and promote strong, innovative and inclusive growth? In looking for answers, they need to be mindful of the potential long-term growth impact of risk-mitigating measures and to preserve economies’ capacity to invent new ways to prosper.ii Mitigating risks can also have costs: in considering policy measures to reduce risks, the benefits need to be balanced against the potential costs in terms of the lower average growth that some policy measures could entail.

[i] Crisis instances are taken from Babecký, J. et al., (2012), “Banking, Debt and Currency Crises: Early Warning Indicators for developed Countries”, ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1485. A crisis is identified if at least one study claims that a crisis occurred. Severe recessions are identified using the Bry-Boschan algorithm to detect peak and trough dates of business cycles. Severe recessions are defined as falls in GDP per capita from peak to trough greater than the median fall over the entire country-year sample, which is somewhat above 3 % of peak GDP per capita.

[ii] Phelps, E. (2013), Mass Flourishings: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge and Change, Princeton University Press.

Proposal

Policy makers should focus on identifying and implementing cost-effective measures that reduce the risks of crises and make our economies more resilient. Improving resilience, in turn, will enhance inclusiveness, by lowering job and income losses, which often hurt lower-income groups most during severe downturns, while promoting capital reallocation, productivity growth and job creation. When risk-mitigating measures involve a trade-off between growth and crisis risk, the most cost-effective actions need to be identified, spanning both macro and structural policies.

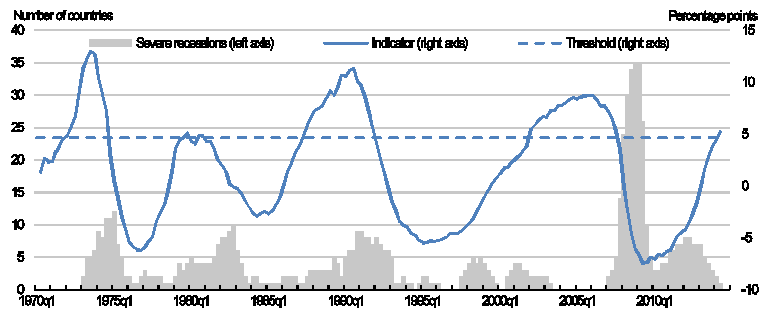

OECD empirical work sheds light on possible growth-crisis trade-offs from two angles: a) looking at the extent to which pro-growth policies can make economies more vulnerable to crises and severe recessions; and b) assessing the impact of risk-mitigating (prudential) policies on growth.[iii] These issues are explored using an empirical approach that provides insights on the impact of various policy settings on average GDP growth on the one hand and either financial crises or exceptionally low GDP growth rates on the other. OECD work provides indications about the areas where policy reforms boost growth and resilience (the top-left quadrant in Figure 1) and the ones where reforms can generate trade-offs (the bottom-left and top-right quadrants also in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Policy areas in a growth-fragilty framework

Note: Structural policies should be assessed on the basis of their effect on growth and economic fragility. In this chart, the effect of policies on economic fragility is plotted on the horizontal axis, the effect on growth is shown on the vertical axis. Fragility is defined as a higher likelihood of financial crises (banking, currency, or twin crisis) or a higher GDP (negative) tail risk. Different risk-growth patterns emerge for each policy area considered—pro-growth labour and product market policies improve economic performance without substantially affecting economic fragility. Better quality of institutions both increases growth and reduces economic fragility. However, macroprudential and financial market polices entail a growth-risk trade-off—the former decrease economic risk to the detriment of a higher growth rate, the latter promote growth but also increase financial risk.

Source: Caldera Sánchez, A., A. de Serres, F. Gori, M. Hermansen and O. Röhn (2016), “Strengthening Economic Resilience: Insights from the Post-1970 Record of Severe Recessions and Financial Crises”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing.

[i] See Caldera Sánchez, A., A. de Serres, F. Gori, M. Hermansen and O. Röhn (2016), “Strengthening Economic Resilience: Insights from the Post-1970 Record of Severe Recessions and Financial Crises”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing.

Product and labour market policies

Product and labour market reforms, which boost growth by making economies more productive and create jobs, generally appear to have little impact on crisis risk. Empirical analysis indicates that they neither reduce nor raise the likelihood of severe recessions.iii However, there are a few exceptions. Stronger active labour market programmes (ALMPs) result in higher average and more inclusive growth as well as less extreme negative tail risks.iii In addition they facilitate hiring [iv] and enhance the boost employment benefits of pro-competitive reforms.[v] Policy settings that reduce labour market segmentation, including by reducing employment protection for regular workers where it is excessive, raise the resilience of labour markets during severe recessions. Coordinated collective bargaining can mitigate the employment effects of severe recessions by promoting wage and working time adjustments. Reducing import tariffs can have a favourable impact on average growth through increased trade openness but also through lower crisis risk.

Civil justice

Higher-quality institutions (e.g. more effective government, greater voice and accountability, better control of corruption) are associated with higher GDP growth, through stronger productivity growth, and a lower incidence of severe recessions. An especially important set of institutions is legal and judicial: sound legal frameworks and infrastructure that guarantee the enforcement of private contracts, provide adequate protection of property rights and promote arm’s length transactions are good for both growth and resilience. In some emerging market countries, an important step towards improving the quality of institutions is to establish corporate governance arrangements that ensure independence from government. Reform in this direction would also have positive side effects in terms of avoiding “shadow fiscal stimulus” that can result in excessive, stability-threatening corporate debt accumulation.

Financial market policies and capital account openness

Financial market reforms involve more direct and substantial trade-offs between growth and crisis risk. At the global level, countries with more liberalised and open financial markets experience higher efficiency gains, but these gains, at the margin, diminish and then become negative when financial depth becomes large.[vi] The benefits in terms of average growth, when they materialize, are largely offset by the higher risk of banking crises and hence severe recessions. This is particularly true for advanced economies, where financial liberalisation can go too far and result in credit excesses that reduce long-term growth and increase inequality. In emerging-market economies, because markets are less well-developed, financial liberalisation has tended to enhance financial inclusion, but at the cost of rapid increases in debt and rising default probabilities of domestic banks.

Countries can make their financial system more balanced and growth-friendly by helping diversify funding sources away from excess reliance on banks. OECD evidence underlines that high reliance on bank lending slows growth and widens inequality, by comparison with more balanced funding that gives more space to capital markets.[vi]

The risk of crises can be mitigated through effective supervisory and prudential policies, which are associated with a lower incidence of severe recessions. The design of prudential policies matters: tools that can nip boom-bust dynamics in the bud, such as maximum debt-to-income ratios, improve stability at no cost to trend growth; tools that leave room for asset-price bubble dynamics, such as maximum loan-to-value ratios, entail trade-offs between stability and long-term average growth.

Greater capital flow openness raises overall economic growth in most cases but also increases the risk of a banking or currency crisis. In practice, the nature of capital flows matters. Among the different types of capital movements, debt flows are the ones that are associated with higher crisis risk. Both foreign direct investment and the equity portion of portfolio investment have no significant effect on crisis risk. Policy design should take seriously into account the risk of a sudden stop of capital flows and the constraints imposed on monetary policy, without unwarranted priors. Though not strictly considered a prudential policy, a higher accumulation of international reserves is associated with less extreme negative tail risks and a small positive impact on average growth.

Macro framework

Specific characteristics of the macroeconomic framework also have implications for the growth-crisis risk nexus. For instance, countries with a free floating exchange rate are found to experience a lower probability of currency crisis (as exchange rate flexibility helps to limit the build-up of foreign-denominated liabilities). Exchange rate adjustments can play a powerful role as a risk sharing and shock absorbing mechanism, provided that the shock does not hit too many countries simultaneously. In addition, exchange rate flexibility limits the risk of persistent misalignments that can bias saving and investment, hurting long-term growth and resilience. Also, countries with stronger automatic stabilisers experience less extreme negative tail risks and are better able to mitigate the rise in inequality caused by a crisis, as the great recession has demonstrated. However, strong automatic stabilisers, such as provided by generous unemployment insurance, mean high government expenditure and/or transfers, the funding of which may have implications for efficiency and growth, in addition to the potential effect on work incentives. Indeed, OECD research shows that higher automatic stabilisers reduce the economic costs of recessions but also average growth rates (though both effects are small).iii Rather than permanently inflating automatic stabilisers, countries can respond to deep crises through discretionary fiscal spending, in particular public investment, which is highly effective in stabilising demand and labour market outcomes during severe economic downturns.

Some policy implications

One of the main implications is that taking measures in the financial sector to lower the risk of severe recessions is entirely appropriate. However, focusing too narrowly on that sector is unlikely to be sufficient and could entail costs in terms of foregone GDP growth where the financial sector is still relatively under-developed. In the latter instances, financial and capital market development, while implementing best-practice regulatory methods, would help to lower the costs of recovering from a financial crisis.

Policy makers also need to consider other sources of distortions that can contribute to the build-up of vulnerabilities to crises, which requires identifying the types of economic imbalances or misalignment that seem to be most closely associated with crisis vulnerability. Following the crisis, and subsequent calls to better identify risks, international organisations such as the OECD, IMF and BIS, as well as national institutions responsible for promoting financial stability, have developed large sets of indicators to detect potential threats to economic and financial stability. For instance, the OECD regularly monitors and reports these dashboards in publications such as the Economic Outlook and Economic Surveys of member countries.

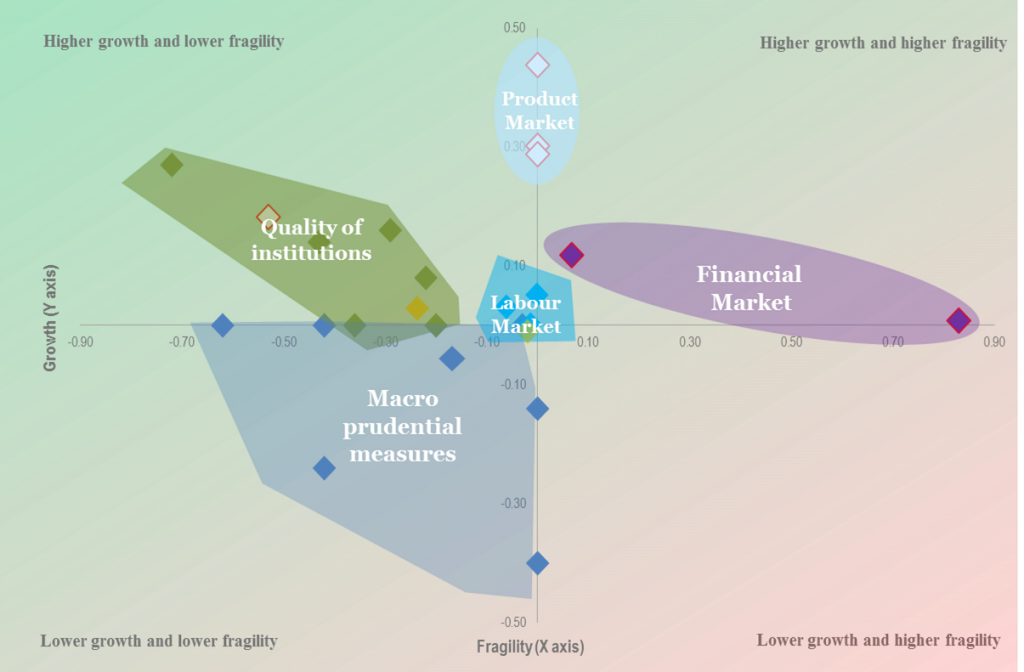

All these indicators shed light on rising imbalances and other developments that can put the health of the financial and economic system at risk. However, some indicators have a much better track record for signaling a severe recession. OECD research shows that, among the factors creating an environment prone to severe recessions, some of the more important ones include rapid growth of private credit, imbalances in the housing market (real house prices, house price-to-income ratios and house price-to-rent ratios) and, to a lesser extent, large current account imbalances. This points to the need to look at how domestic policy distortions, notably in the area of regulation and taxation, contribute to excess leverage, in particular through real estate markets. Higher inequality, by itself, can also contribute significantly to credit growth, potentially generating a two-sided causality relationship prone to increasing instability. [vii] Furthermore, rapid increases in private credit and public borrowing can cause sustained current account imbalances that are also associated with recession risk. An emerging source of financial risk may arise from digital currencies, where the possibility cannot be excluded that bubbles are developing.

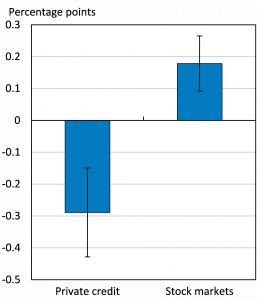

This is consistent with related OECD work showing that among advanced economies more private credit is associated with lower long-term growth and stock market financing with higher growth (Figure 2, Panel A). Furthermore, among the different sources of credit and their impact on-long term average growth, bank lending is found to be much more negative than bond borrowing, and economies with a high bond share tend to recover from recessions faster.[viii] Moreover, household credit appears to exert a stronger drag than business credit. The rise of finance is also empirically linked with increases in income inequality because credit is concentrated among those who can pledge collateral and also because the financial sector directly contributes to income inequality by paying very large wage premia to its employees, especially at the top.[ix] More bank credit and larger stock markets are both correlated with a less equal distribution of household income, when accounting for many other factors (Figure 2, Panel B).

An avenue of financial reform that can deliver progress towards both sounder, more stable growth and better equality would be to abolish all regulatory provisions that favour a banking model based on collateralisation. Favourable regulatory treatment of collateralised credit hurts growth and stability by giving an advantage to property, contributing to damaging boom-bust cycles. Favourable treatment of collateralised credit also gives an edge to incumbents and heirs when it comes to the funding of new, profitable ideas, contributing to wealth inequality and working as an obstacle to intergenerational mobility. Repealing such provisions would make financial regulation more growth, stability and equity-friendly. One option for consideration to progress further would be to facilitate human capital based lending by utilizing the big data on individual’s history of financial transactions.

Figure 2. Equity Finance has been more favourable to growth than credit finance

A. Effects on GDP growth per capita B. Effects in income equality

Note: The bars show the effects of a 10% of GDP increase in private credit or stock market capitalisation. Private credit is credit to the non-financial private sector by banks and similar financial institutions, and stock market capitalisation is the value of all shares listed in a stock market. Black segments indicate 90% confidence intervals.

Source: Cournède, B. and O. Denk (2015), “Finance and Economic Growth in OECD and G20 Countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1223, OECD Publishing; Denk, O. and B. Cournède (2015), “Finance and Income Inequality in OECD Countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1224, OECD Publishing.

Housing policy

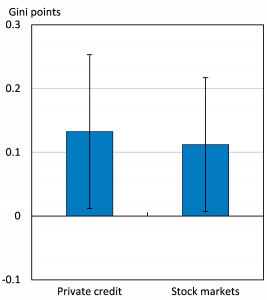

Taken together, these results flag that the functioning of the real estate market, in particular housing, is at the heart of most severe recession. For instance, severe recession over the past four decades have often been preceded by significant housing price misalignments (Figure 3). In many countries, specific features of the housing market are conducive to excessive mortgage borrowing and leverage, including the tax treatment of housing. This is often biased in favour of ownership using mortgage-based modes of financing and therefore tends to benefit more affluent households disproportionately, while exacerbating intergenerational wealth inequality. The impact of taxation can magnified by regulation and other distortions that restrict the supply of new housing, contributing to price bubbles in the market and inequality in access to home ownership. Relaxing constraints in land use is a win-win measure to reduce house price-bubble risk, improve economic efficiency (including through easier geographic mobility by increasing its costs, especially where the bias in favour of home ownership is combined with high taxes on housing transactions. Consequently, making tax systems neutral between housing and other assets would improve financial and labour market resilience while delivering growth and intergenerational equity benefits.

Figure 3. Housing price cycles have often been associated with severe recessions

Global real house price index

Note: Grey areas represent the number of countries identified as being in a severe recession (from peak to trough). The global real house price index is constructed as a GDP-weighted average across OECD countries is measured in deviation from trend.

Source: Hermansen, M. and O. Röhn (2016), “Economic Resilience: The Usefulness of Early Warning Indicators in OECD Countries”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2016, OECD Publishing.

Tax reform beyond housing

In the non-financial corporate sector, tax systems in most countries also favour debt over equity financing. This bias to a large extent contributes to excessive credit accumulation, bank leverage and asset price bubbles, which generate risk, reduce average long-term growth and increase inequality.

Managing global capital flows

Insofar as policies distorting private saving and investment decisions fuel large current account imbalances, reforms of those policies would also help reduce crisis risk over time. In some cases, risk-mitigating policies in one country can result in higher risk elsewhere. One example is the reliance on international reserves as buffers against crises. Following the crisis that hit many countries in South East Asia in the late 1990s, governments in these countries – not least China – built up vast reserves, which later contributed to growing current account imbalances and cross-border capital flows, which in turn exacerbated the 2008-09 crisis. More generally, since current account imbalances reflect countries’ net savings, they are influenced by fiscal and investment policies. But the counterpart to current account imbalances is capital flows and, as previously mentioned, the nature of the flows associated with the imbalances is an important factor of vulnerability to crisis risk. For a given imbalance, both foreign direct investment and portfolio investment in the form of equity are preferable to debt flows. Tax, investment and financial policies can all influence the balance of equity and debt within capital inflows. Against a background of persistently weak demand and slowing productivity, the fact that both leverage and current account imbalances have remained at levels that show little improvements since the crisis is clearly a source of concern. The policy effort required to reduce risk involves shifting incentives to deepen capital markets, ensuring appropriate regulatory and supervisory practices and lowering excess reliance on bank and portfolio flow financing: a key ingredient is to eliminate de facto subsidies for too-big-to-fail banks. Dependence on portfolio inflows might also be addressed with more sustainable and growth-oriented fiscal policies.

In addition to financial reform, tax and structural reforms can unlock considerable potential for greater economic resilience: removing tax advantages for housing, easing land-use rules, facilitating geographical mobility and making labour markets more flexible would enhance resilience as well as boost growth. Finally the more proactive use of indicators that presage economic downturns and crises would be a critical addition to country’s policy making process.

References

- Crisis instances are taken from Babecký, J. et al., (2012), “Banking, Debt and Currency Crises: Early Warning Indicators for developed Countries”, ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1485. A crisis is identified if at least one study claims that a crisis occurred. Severe recessions are identified using the Bry-Boschan algorithm to detect peak and trough dates of business cycles. Severe recessions are defined as falls in GDP per capita from peak to trough greater than the median fall over the entire country-year sample, which is somewhat above 3 % of peak GDP per capita.

ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1485 - Phelps, E. (2013), Mass Flourishings: How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge and Change, Princeton University Press.

How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge and Change. Princeton University Press - See Caldera Sánchez, A., A. de Serres, F. Gori, M. Hermansen and O. Röhn (2016), “Strengthening Economic Resilience: Insights from the Post-1970 Record of Severe Recessions and Financial Crises”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing.

OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 20 - OECD (2015), “Activation Policies for More Inclusive Labour Markets”, Chapter 3 in OECD Employment Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing.

Chapter 3 in OECD Employment Outlook 2015 - Cournède, B., O. Denk, P. Garda and P. Hoeller (2016), “Enhancing Economic Flexibility: What Is in It for Workers?” OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 19, OECD Publishing.

OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 19 - Cournède, B., O. Denk and P. Hoeller, “Finance and Inclusive Growth”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 14, OECD Publishing.

OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 14 - Bazillier, R and J. Hericourt (2017), “The Circular Relationship between Inequality, Leverage, and Financial Crises”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 461-496, April 2017.

Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 461-496 - Thomas Grjebine & Fabien Tripier (2016), “Finance and Growth: From the Business Cycle to the Long Run,” CEPII Working Paper 2016- 28 , December 2016.

CEPII Working Paper 2016- 28 - Bazillier, R and J. Hericourt (2017), “The Circular Relationship between Inequality, Leverage, and Financial Crises”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 461-496, April 2017.

Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 31, Issue 2 - Grjebine, T, U. Szczerbowicz & F. Tripier (2014), “Corporate Debt Structure and Economic Recoveries,” CEPII Working Paper 2014- 19, November 2014.

CEPII Working Paper 2014- 19 - Denk, O. (2015), “Financial Sector Pay and Labour Income Inequality: Evidence from Europe,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1225, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1225