Migrants (especially women) are particularly vulnerable to the economic crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. The resulting rising unemployment and social tensions make economic and social inclusion distant, challenging goals for sending and receiving countries. Globally, the pandemic will lead to increased precarity and heightened poverty levels among migrant workers.

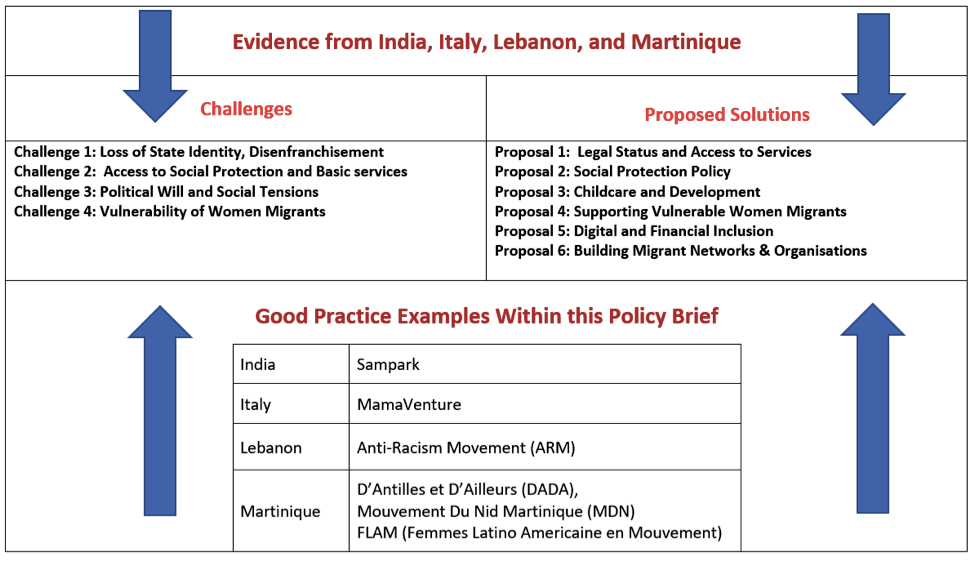

To address this challenge, we focus on solutions in four key policy areas that can provide migrant workers and their families dignified and secure livelihoods post COVID-19: social protection; child development; digital and financial inclusion; and economic protection and support for vulnerable women. We present solutions modelled on successful interventions in India, Lebanon, Martinique and Italy.

Challenge

Challenge 1: Loss of State Identity, Disenfranchisement

As migrants move across borders, they lose their state identity and the rights this confers. Their identities, needs, access to health care, and social protection disappear (Prabhu, 2020). Further, asylum and residency procedures are often lengthy. In India, where over 100 million migrants in 2016 were circular migrants, the problem is exacerbated by the transitory nature of migration, further hindering administrative action. Without formal identity, voice and recognition, migrant workers lose their agency to fight for and protect their basic rights. Addressing the challenge of granting administrative status to migrants, to improve their agency and reduce discrimination is key, especially for addressing precarious and exploitative work in the informal sector.

Challenge 2: Access to Social Protection and Basic Services

Migrant workers are plagued by an absence of social protection and safety nets. UN data suggests only 22 per cent of migrant workers had employment and/or social protection at their destination (UN). In India, with informalisation on the rise,1 a lack of data resulted in a tragic crisis for migrant workers during the pandemic (Premchander and Pande, 2020). In Europe, the scale and pace of incomers has been such that “the prospect of expanding local services to meet these needs is overwhelming to many communities” (MPIE, 2017). The ILO highlights the need for social protection to reduce poverty and inequality (2019b). Lack of dynamic data systems which provide gender-disaggregated data for policy formulation, alongside the lack of funding, frustrate the provision of basic services.

Challenge 3: Political Will and Social Tensions

The beneficial role of migration in sustainable development in both host and origin countries is now more widely accepted, yet governments face a profusion of difficulties in developing and implementing migration integration policies. The complex and delicate nature of the multilateral agreements required makes progress slow, though the idea of “minilateral” agreements may offer a practical way forward (Newland, 2017). There is a political understanding that the “rationale for investing in labour market integration lies in the early access to decent work which is essential to integration and social inclusion more broadly” (Desiderio, Rienzo and Benton, 2016). Yet, many governments are slow to grant migrants legal status and the access to the labour market this allows. In political discourse migrants are frequently portrayed as groups in need of humanitarian assistance rather than those able to contribute to development. This naturally fuels the social tensions amongst nationals and incomers evident in European cities such as Berlin, Peru’s Venezuelan migrants, and India’s tensions with Bangladeshi and Rohingya migrants. The costs of providing sustained and substantial integration policies, coupled with rising xenophobia and social tensions are key barriers to mobilising political will and realising the benefits of migrant integration.

Challenge 4: Vulnerability of Women Migrants

The WHO highlights the consequences of “the continued lack of safe and regular migration pathways and gender responsive policies” which puts migrant women (68 million globally in 2017) at “high risk of employment rights abuses, sexual and gender-based violence, racism and xenophobia” (WHO, 2017). Martinique is one of many examples where women’s migration has forced them into prostitution and exploitation (IFRC, 2018). In India, the primary responsibility for childcare prevents women from working and earning incomes, exposing children to malnutrition, and to harm when uncared for, including child rape.

Only 54 per cent of global governments report having formal mechanisms to ensure migration policy is gender responsive (UN, 2020). Among the EU member states, only 7 of 32 had policies that focus on the integration of women migrants (EU Fundamental Rights Agency, 2018; EU Court of Auditors, 2018).

Proposal

The key themes of our proposal are: providing access to integration services and social protection to migrants; strengthening their voice; services to protect children and provide economic and networking support to vulnerable migrant women; and enabling digital and financial inclusion. The policy brief highlights the importance of strengthening multifaceted partnerships with migrants, NGOs and local government, and public and private sector partnerships to promote access to the labour market.

Proposal 1: Give Legal Status and Access to Services along Migration Pathways

Granting legal status (tied directly to SDG 10.7 Regular and orderly migration) and access to the rights and services this allows is a key part of removing current barriers to protecting and integrating migrants. Access to rights and services along the migration pathways (including circular pathways, as in India) is an important policy goal, requiring cooperation among states.

Addressing the slow and expensive process of providing asylum and residential status, Peru has successfully trialled a Temporary Stay Permit. It has streamlined the process for granting 600,000 migrants temporary residence for one year (MPI, 2021), providing an important route to obtaining permanent residency.

Public communication strategies to address social tensions are recommended across many initiatives, and Berlin’s ARRIVO project tackles these tensions head-on with matched-employment strategies, where schemes employ one long-term unemployed national for each newcomer (ARRIVO Project, 2021). In Martinique (DA&DA) and in Lebanon (ARM) migrant organisations focus on cultural activities to promote social inclusion and tackle xenophobia.

Proposal 2: Raise Funds for Social Protection and Make Services Portable (SDG 1.3)

Policy experts highlight the importance of sustaining the funding of integration services and policies over time, as the integration of newcomers into host communities takes considerable time (MPIE, 2017). ILO estimates suggest that a social protection package in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) would cost 2.4 per cent of their GDP. Raising tax revenue to fund social protection is one financing option put forward by the ILO (ILO, 2019a).

An innovative example of this is India’s law for raising resources and providing social protection for construction workers. The Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Cess Act of 1996, India, mandates that 1 per cent of construction project budgets be deposited with Construction Workers Welfare Boards. This national policy ensures corporate investment in the welfare of construction workers; the national cumulative resources in 2019 totalled approximately USD 28bn. These funds proved useful during the pandemic, when over USD 600 million was disbursed to migrant workers in the form of Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) and food provisions across the country (PIB, 2020).

In the Indian state of Karnataka, the Karnataka Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board (KBOCWWB), established in 2007, has 1.7 million workers registered (April 2021).2 The Board’s resources stood at a cumulative USD 757 million in 2017 (Narayana, 2019). The Karnataka Welfare Board provides free bus passes as well as grants for maternity, education, marriage and housing. During the pandemic lockdown in Karnataka, 1.58 million workers received DBTs of between USD 40-67. The Board distributed 78,000 bus passes. Accessible mobility allows workers, especially migrant women, the freedom of safe mobility to access immunisations and health services for their children and families; to find work; and to promote their enterprises, materially improving their welfare.

However, the Boards have had difficulty using the funds collected. Across India, the Boards had utilised just over 25 per cent of the funds by 2019 (Raibagi, Banerjee and Indiaspend. com, 2019), and Karnataka had utilised only 6 per cent (Narayana, 2019). Civil society can play an important role in addressing these challenges of awareness and access to services. NGOs like Bangalore-based Sampark make workers aware of their rights to social protection by providing information in various languages, and assist them in registering with the Board, contributing to its credibility within the community. Sampark has established Worker’s Resource Centres (WRCs) to empower migrant construction workers, raise awareness of social protection schemes available from the Welfare Board and enable access to health, education and financial inclusion. Through these WRCs the organisation has reached out to over 25,000 workers since 2013. By promoting registration with the Welfare Board, it has enabled over 8,000 workers (40 per cent women) to register and access the scheme’s benefits. This model can play a large role in promoting social protection outcomes. The Welfare Boards and Cess tax are important components to promote social protection, but these must be coupled with awareness and access to schemes promoted by government and civil society to reach the voiceless population.

PORTABILITY OF SUBSIDISED FOOD SUPPORT

A prominent example in India is the case of food security, an integral component of social protection frameworks. The Food Security Programme in India relies on a Public Distribution System comprising a network of shops where low-income beneficiaries can access subsidised food grains through a ration card. There has been no portability of these benefits across states, posing severe challenges for migrant workers who have left their home state. Following successful advocacy by NGO networks, the Indian government announced the portability of these ration cards through the “One Nation One Ration Card” scheme. This policy initiative will provide over 80 million internal migrant workers with access to food and water at low cost. Previously administered at the state level, these have now been scheduled for adoption at the national level, through linkage with national identity cards.

Proposal 3: Provide Child Care & Development Centres

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) services are an effective measure to address the health, nutrition and education needs of migrants’ children.3 Such services help to realise the twin goals of increasing countries’ ability to compete in the global market and alleviate the effects of persistent poverty (CGECCD, 2016). Well-designed investments in ECEC services can have major economic and social payoffs for families, individuals and societies at large by: (a) facilitating women’s participation in the labour force (Premchander et al., 2021), (b) enhancing children’s capabilities and (c) creating decent jobs in the paid care sector (UN Women, 2015).

Sampark, an NGO, runs daycare centres in Bangalore, India, for children (6 months to 14 years old) of migrant workers. These early childcare and development centres are located on construction sites and labour settlements, and provide childcare, nutrition and immunisation support, education and health awareness (Ramakrishnan, 2019). Since 2007, Sampark has established 50 such centres throughout Bangalore, reaching more than 7,000 children of construction workers. The stimulating child-led learning environment at the centres using English and regional languages builds confidence in migrant children. Since 2007, Sampark teachers have facilitated admissions for over 1,000 migrant children into public schools to which the children should have rightful access. Eighty per cent of mothers have been able to join the labour force and work without having to leave their children unprotected.

Assessment of children using new WHO child growth standards is an important component of the intervention as 26 per cent of children enrolled in these centres are malnourished; these children are given special diets to ensure growth and well-being. Pregnant women in the labour colonies are identified and linked to state childcare centres to receive preand post-natal nutrition, vaccines and medicines. Linkages for immunisation are prioritised and in the last three years 660 children were immunised. Regular health check-ups identify children’s illnesses and over 1,500 children were linked to health centres/hospitals for treatment in the last three years. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic 42 per cent of malnourished children improved their nutrition levels.

With Sampark’s advocacy the centres, initially funded by corporate and charitable donors, were funded by KBOCWWB. Following Sampark’s success for the pilot government-NGO partnership, KBOCWWB upscaled its project to run 100 more centres across Karnataka. These crèches are seen to be easily replicable across different contexts, where key linkages can be made with NGOs, local government, health centres and schools.

Proposal 4: Support Vulnerable Women Migrants with Integrated Services and Economic Opportunities

The examples presented here demonstrate the value of multi-stakeholder partnerships in securing protection and economic empowerment for migrant women.

To respond to the needs and dignity of migrant women fallen into prostitution and shifting their positionality in Martinique from exploited human beings to empowered women, three feminist activist organisations D’Antilles et D’Ailleurs (DA&DA), Mouvement Du Nid Martinique (MDN) and the migrant women-based organisation FLAM (Femmes Latino Americaine en Mouvement) launched an integrated support service.

The MDN offers primary services to migrant women who have been forced into sex work. These include administrative, legal, employment, language, psychological and healthcare support, and access to social rights. The organisation trains social workers, police and lawyers about sexual exploitation and victim support. DA&DA promotes cultural diversity and fights against stereotypes and discrimination through cultural activities, education, acquisition and recognition of competences of migrant women. FLAM provides cultural mediation and facilitates the inclusion and integration of Latin American migrant women through individual and group events.

The unifying and complementary strategy across partner organisations ensures best use of resources, avoids overlapping services and addresses the many facets of migrant support needs. Partnerships established with various stakeholders support women with micro finance, employment and housing needs. The legal support offered is important in providing an exit path out of prostitution.

As a route out of prostitution, economic empowerment for migrant women is vital and social enterprise ventures have proved a successful means to achieve this. One successful social enterprise in Serbia which employs women victims of trafficking and redirects the profit to programmes that support migrants, particularly victims of trafficking, has won acclaim. Mama Venture is a successful example from Italy that supports the economic inclusion of migrants by financing startup businesses. Mama Venture is Italy’s first investment fund entirely dedicated to migrant talents with entrepreneurial ideas. Other Italian examples include Articolo 10 and COLORI VIVI a tailoring workshop that produces accessories and women’s clothing and MULTIVOLTI in Palermo a social enterprise that combines a restaurant, a co-working space, a not-for-profit organisation and a responsible tourism enterprise.

These social enterprises combine profit making with the cause of economic inclusion and empowerment of migrant workers, and when facilitated by NGOs or investment funds, provide much needed economic security to vulnerable women migrants. The Martinique initiatives underscore the effectiveness of a feminist, integrated and multi-disciplinary approach to making women’s needs visible and addressing them.

Proposal 5: Increase Digital and Financial Inclusion

As digital technologies become more important in everyday lives of people in developing countries, those without access to ICT are increasingly excluded from vital services. While 90.6 per cent of adults in high-income countries have an account with a formal financial institution, the same is true for only 54.1 per cent of adults in LMICs (Demirguc-Kunt et al.,

2015). Policy interventions focusing on using digital technology to address financial inclusion would have a substantial impact on migrant workers.

In India, Sampark supported over 10,000 migrant workers to apply online for membership with the Welfare Board, allowing them access to the Board’s welfare schemes. Sampark assisted the workers to procure national identification cards (Aadhaar cards) and to open Aadhar-authenticated bank accounts. During COVID-19, this digital and financial inclusion of migrant workers enabled them to receive benefits that the Karnataka Board distributed to state and inter-state workers alike, enabling real inclusion. These interventions directly increased identity and financial inclusion for migrant workers and enabled their access to welfare services. Furthermore, this digital inclusion initiative has resulted in migrants’ inclusion in government databases, thus crucially giving them a place in the COVID-19 vaccination scheme.4

In Lebanon (via ARM) and Martinique, NGO-run Migrant Community Centres have prioritised digital access and training for migrant workers to develop competencies and employability. The integrated approach to supporting women migrants in Martinique purposefully includes the services of a microcredit organisation which funds and advises businesses.

These inclusive policy interventions for digital and financial inclusion and services are particularly beneficial and replicable in large migrant worker communities.

Proposal 6: Build Migrant Networks & Organisations

The vulnerability of migrants themselves is the principal obstacle to promoting migrants’ rights, outweighing the lack of legislation and the limited reach of inventive unions and activists. As migrants are wholly dependent on their contractor-employers, most are reluctant to challenge them; to complain or to organise is to forfeit employment and few can afford to do so (Mosse et al., 2005). One solution is to build the networks and support groups required to support migrants.

Migrant Resource Centres (MRCs) or Workers Resource Centres (WRCs) are increasing in many countries, including India, Lebanon, Serbia, Jordan, Vietnam and Cambodia. Many are supported by international agencies such as the ILO, as well as local civil society organisations (CSOs) and trade unions. These centres help migrants to obtain counselling, essential support services and accurate information (Premchander, 2018).

In India, Sampark’s WRCs were instrumental in increasing the agency of workers, by helping them organise into unions that can advocate for the interests of the collective. This unionisation increases the collective voice and ensures greater bargaining power. This is an integral step in the long-term protection and integration of migrant workers. As migrants are extremely vulnerable to exploitation, creating mechanisms to prevent wage exploitation is as important as creating the means of economic inclusion. 5

In Lebanon, a grassroots collective of young Lebanese feminist activists, migrant workers and migrant domestic workers launched the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) in 2010. ARM has created a network of Migrant Community Centres (MCCs) throughout the country to improve the quality of life of migrant workers, to empower them on their socio-economic rights and to contribute to an influential migrant civil society. The MCCs provide migrant workers a safe space to meet freely and work together, learn new skills and access information. Since their creation, the MCCs have offered free services including education, language, health and digital literacy classes, rights and advocacy training, and cultural exchange events.

ARM also demonstrated the role of worker’s collectives in responding to catastrophic economic crisis. To support the stranded migrant workers who have been disproportionately affected by Lebanon’s combination of pandemic, economic crisis and Beirut blasts, ARM prioritised food distribution and housing support as well as evacuation to their home countries. ARM worked with embassies, consulates and the Lebanese Ministry of Labour during these times. Given the failed systems throughout the country, advocating for the stranded migrant workers is crucial yet very challenging.

Workers community centres have proved useful in enabling service provision, rights awareness, networking and informal support among migrant workers and by CSOs. They empower migrants and greatly improve their prospects.

CONCLUSION

Our recommendations focus on improving the lives of the most vulnerable groups of migrants: stateless migrant workers, women facing exploitation and those living in crisis zones. The lack of gender-disaggregated data globally remains a significant barrier to data collection and implementing appropriate policy to protect and support women migrants.

These policy initiatives have made clear contributions to the welfare and inclusion of migrant workers and may be adapted and scaled up for widespread application. They make a significant contribution to lasting social cohesion as well as the GDP of both origin and host countries. The economic benefits of integration are measurable at the “aggregate country level and for individual households” (Danzer, 2011).

Figure 2: An interlinked system that promotes the empowerment and well-being of migrants

NOTES

1 Informal employment nearly doubled to 49 million between 2004-05 and 2011-12 in the Indian construction industry.

2 Although overall membership data is available, gender-disaggregated data on memberships and on benefits provided is not available in the public domain.

3 Tied to SDG 4 Ensuring quality education opportunities for all.

4 Sampark has also organised outreach vaccination camps to ensure the COVID-19 vaccination of migrant workers.

5 Sampark has mediated wage disputes worth nearly USD 74,000 so far.

REFERENCES

ARRIVO Berlin, https://www.arrivo-servicebuero.de

Danzer, Alexander M. (2011), “Economic Benefits of Facilitating the Integration of Immigrants”, in IFO

Demirguc-Kunt, A.; L. Klapper; D. Singer; and P. Van Oudheusden (2015), “The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring Financial Inclusion Around the World”, in World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, No. 7255

Desiderio, Maria Vincena; Cinzia Rienzo; and Meghan Benton 2016, Evaluating Returns on Investment in the Labour Market Integration of Refugees and Asylum Seekers: A Holistic Approach, Brussels and Gütersloh, Germany, Migration Policy Institute and Bertelsmann Stiftung

Dhal, M. (2020), “Labor Stand: Face of Precarious Migrant Construction Workers in India”, in Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 146, No. 6, 04020048

EU Fundamental Rights Agency (2018), EU Court of Auditors 2018, https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/Briefing_paper_Integration_migrants/Briefing_paper_Integration_migrants_EN.pdf

IFRC (2018), Alone and Unsafe: Children, Migration and Sexual and Gender Based Violence

ILO (2019a), High Level Conference Geneva, “Universal Social Protection by 2030”

ILO (2019b), Measuring Financial Gaps in Social Protection: Estimates and Strategies for Developing Countries

Pattenden, Jonathan (2018), “The Politics of Classes of Labour: Fragmentation, Reproduction Zones and Collective Action in Karnataka, India”, in The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45:5-6, pp. 1039-1059, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2018.1495625

KSCOWWB (2021), https://karbwwb.karnataka.gov.in/

Lipton, M. (1980), ”Migration from Rural Areas of Poor Countries: The Impact on Rural Productivity and Income Distribution”, in World Development, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 1-24

Prabhu, Maya (2020), “Invisible to Everyone, But Safe Together: Life in a Labour Colony”, in Al-Jazeera, 5 March

Mosse, D.; S. Gupta; and Vidya Shah (2005), “On the Margins in the City: Adivasi Seasonal Labour Migration in Western India”, in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 40, No. 28, pp. 3025-303

Narayana, M. R. (2019), “Organizing Old Age Pensions for India’s Informal Workers: A Case Study of a Sector-Driven Approach”, in Stanford Asia Health Policy Program Working Papers, No. 47, 3 April

Newland, K. (2017), The Global Compact for Migration: How Does Development Fit In?, Washington DC, Migration Policy Institute

Pattenden, J. (2016), Labour, State and Society in Rural India: A Class-Relational Approach, Manchester, Manchester University Press

PIB (2020), Two Crore Building and Other Construction Workers (BOCW) Received Cash Assistance of Rs 4957 Crore During Lockdown, Government of India, 23 June

Premchander, Smita (2018), Final Independent Evaluation, Work in freedom (ILO-DFID Partnership programme on Fair Recruitment and Decent Work for Women Migrant Workers in South Asia and the Middle East), ILO

Premchander, Smita; Aindrila Mokkapati; and Deepika Pingali (2021), “Unequal Access: Women and Their Livelihoods in 2020”, in State of India’s Livelihoods 2021, New Delhi, Sage Publications

Premchander, S.; and R. Pande (2020), Rapid Assessment of Migrants Health Awareness and Economic Situation under COVID19 and Lockdown

Raibagi, Kashyap; Abhivyakti Banerjee; and Indiaspend.com (2019), “Data Check: 23 Years On, a Welfare Cess for Construction Workers Has Done Little for Them”, in Scroll.in, 22 April

Ramakrishnan, A. (2019), “Some Hand-Holding for Migrant Workers’ Kids”, in Deccan Herald

Rashid, A. T. (2016), “Digital Inclusion and Social Inequality: Gender Differences in ICT Access and Use in Five Developing Countries”, in Gender, Technology and Development, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 306-332

Ravindranath, D.; J. F. Trani; and L. Iannotti (2019), “Nutrition among Children of Migrant Construction Workers in Ahmedabad, India”, International Journal for Equity in Health, No. 18, p. 143

Roy, Shamindra; Manish; and Mukta Naik (2018), Migrants in Construction Work: Evaluating their Welfare Framework

Shamala, B.; and T. Rajendra Prasad (2020), “A Study on Welfare Schemes for Migrant Construction Workers in Karnataka”, in International Research Journal

on Advanced Science Hub (RSP Research Hub), Vol. 2, No. 8, pp. 261-267

Srija, A.; and S. Shirke (2014), An Analysis of the Informal Labour Market in India, New Delhi, India, Confederation of Indian Industry

Srivastava, Ravi; and Rajib Sutradhar (2016), “Labour Migration to the Construction Sector in India and Its Impact on Rural Poverty”, in Indian Journal of Human Development (Institute for Human Development), Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 27-48

Rajendraprasad, T.; and B. Shamala (2020), “A Study on Welfare Schemes for Migrant Construction Workers in Karnataka”, in International Research Journal on Advanced Science Hub, Vol. 2, Special Issue ICARD, pp. 261-267

UN Women (2015), Gender Equality, Child Development and Job Creation: How to Reap the ‘Triple Dividend’ from Early Childhood Education and Care Services

Wells, J. (1996), “Labour Migration and International Construction”, in Habitat International, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 295-306

World Health Organization (2017), Women on the Move: Migration, Care Work and Health, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259463