More than a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, many governments, particularly large migrant-sending lowand middle-income countries in the Global South, are met with a large return migrant population with an uncertain future. There is also pressure on these governments, like most governments in the developed world, to make supply chains less vulnerable to shocks from other parts of the world by localising or regionalising them. This policy brief advances a common solution to this seemingly disparate dual challenge that countries of origin face. By prioritising the return migrant community as a central pillar of a new developmental vision and tapping into its financial, human and social potentials, governments can revive their economies and gain a competitive advantage in the post-pandemic era.

Challenge

1. Migration: Large-scale return migration, decreasing remittances and uncertain prospects for future migration.

Countries of origin are facing a dramatic increase in their return migrant population owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. As migrants lost their jobs and faced higher risk of getting infected due to their often overcrowded and unsafe working and living conditions, many of them were forced to return to their countries of origin usually a lowor middle-income country in the Global South. Globally, India has the largest transnational community in the world with 18 million persons of Indian origin abroad (UN DESA, 2020), and as of 19 June 2021, over 6.1 million had returned to India under the official repatriation mission (Ministry of Civil Aviation, 2021). Similarly, nearly 932,000 undocumented Afghan nationals returned from Iran and Pakistan between 1 March 2020and 25 February 2021 (IOM, 2021); and as of 30 October 2020, more than 136,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees had returned to Venezuela from other countries in the region (Migration Data Portal, 2021).

A massive decrease in remittances is the direct result of such large-scale exodus of international migrants to their countries of origin. In 2019, the World Bank had projected that USD 574 billion wouldbe sent to lowand middle-income countries by the end of 2020 (Ratha et al., 2019). In April 2020, the World Bank estimated that remittance flows to lowand middle-income countries would drop by around 20 percent to USD 445 billion, from USD 554 billion in 2019 (Ratha et al., 2020a). By October 2020, the World Bank had revised its forecast decline to USD 508 billion in 2020 and a further decline to USD 470 billion in 2021 (Ratha et al., 2020b). However, it is to be emphasised that the declining trend in remittances is nuanced. For example, in Pakistan where remittance inflows accounted for nearly 8 percent of the GDP in 2019 monthly remittances increased to a historic high in July 2020 (State Bank of Pakistan, 2020). Likewise, in Mexico and Nepal, remittance inflows in the last three quarters of 2020 surpassed those of the corresponding periods in the previous year (Banco De Mexico, 2021; Nepal Rastra Bank, 2021). Therefore, although immediate negative effects on remittance flows may be moderated in the short-term by exchange rate fluctuations and larger transfers of savings during the pandemic (which were the main reasons for this increase in remittance flows), consistently achieving pre-pandemic levels of remittance flows is challenging due to a sustained reduction in migration and increase in return migration. This challenge is further intensified by major changes in the global economy due to the pandemic such as digitisation and automation, that will cause unprecedented modifications in the labour market, making future migration uncertain.

2. Economy: Economic slowdown, vulnerability to global supply chains, increasing healthcare and welfare expenditure, and rise of economic nationalism.

The swift and intense shock of the pandemic, and resultant shutdown measures sent the global economy into a tailspin. The World Bank estimates that the global economy shrank by 5.2 percent in 2020 (World Bank, 2020). This represents the deepest recession since the Second World War (ibid.). Real GDP among G20 countries contracted by 3.4 percent in the first quarter of 2020 comparatively, GDP fell by only 1.5 percent in the first quarter of 2009 at the height of the financial crisis (OECD, 2020). COVID-19 has also halted globalisation in its tracks, at least temporarily. The supply shock that started in China in February 2020, and the demand shock that followed as many major industries of the global economy shut down, exposed weaknesses in the supply chains of firms worldwide. Driven by cheap labour and faster transport and communication, the focus of firms until the start of the pandemic had been to create long and lean supply chains, with product components manufactured and assembled in multiple countries in different regions of the world. Firms are now prioritising resilience over efficiency and are trying to produce and ship their products more locally to ensure less disruption in case of future hurdles in the movement of people and goods. For example, a Capgemini survey found that as many as 65 percent of organisations are actively investing in localising or regionalising their supplier and manufacturing base (Capgemini Research Institute, 2020). Organisations are also investing heavily in nearshoring and digitising their supply chains using technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), which will unquestionably benefit from new and strong regional networks of individuals, firms and governments (ibid.). This trend of localisation/regionalisation is further strengthened by a rise in economic nationalism in many countries a response to years of falling real incomes, rising unemployment and increasing inequality.

Proposal

The post-pandemic development strategy in migrant-sending developing countries needs to address the following challenges:

1. A large return migrant population with uncertain prospects for future migration.

2. A native non-migrant population that might hold antagonistic views towards return migrants.

3. Varied developmental requirements for lowand high-skilled return migrants.

4. Vulnerable local and regional supply chains that are inefficient and outdated in terms of production, trade and technological capabilities.

This policy brief proposes the prioritising of the return migrant community at the countries of origin, and its networks both domestically and regionally to accelerate post-pandemic economic development.

Return migrants are an asset to society. Return migrant groups and networks possess diverse and high value assets:

i. Financial capital accumulated through remittance flows,

ii. Human capital accumulated through experience and training abroad, and

iii. Social capital through kin networks in the origin countries, and personal and professional transnational networks that are embedded both in countries of destination and other countries of origin.

Return migrants, with their varied and sizeable financial, human and social capital, can significantly contribute towards developmental strategies starting with the establishment of new and improved supply chains. They can be influential and effective in creating new supply chains of more varied goods and services of better quality and cheaper prices that use greener technology. Facing uncertain prospects in the short-term, they are looking to engage in economic and social activity in their origin countries. But to do so, they require the support and trust of governments. Towards this end, governments local, provincial and national must: (for concrete examples, see case study of Kerala below)

1. Engage with the return migrant community

Although there is no “one” return migrant community, every origin country has a loose association of returnees. Governments must identify such associations, bring them together, start engaging with them and build trust. For regions with a sizeable return migrant population, a separate department or ministry may be constituted in the government for this purpose. This will not only significantly improve administrative and bureaucratic procedures, but also create a sensitivity within governments on issues facing migrants and return migrants. For instance, the differentiation between low-skilled and high-skilled return migrants is an extremely important one during a pandemic as the health and social security levels of the two groups vary markedly. Moreover, as being a “migrant” or a “returnee” are also identities, governments must aim to unite migrants and returnees in their populace into an inclusive, transparent and democratic community. Governments must actively promote social cohesion between different groups in the populace migrants, return migrants, prospective migrants and non-migrants.

2. Assess the needs and assets of return migrants

Governments must understand the collective needs and assets of the return migrant community to unleash its potential. An important precondition to do this is to have good data sources. Governments must periodically collect migrant and returnee information through large-scale quantitative surveys, understand relationships and processes through qualitative research, and merge them with administrative data. In doing so, governments must regularly inquire into the needs and aspirations of returnees, their assessment of future opportunities in the country/region of origin, their affinity towards becoming a part of the economic and social fabric of their country of origin, and prospects of future migration to earlier destinations or new ones (which should then also be identified).

3. Data sharing between countries of origin in the region (and provincial governments within countries)

Countries of origin, particularly those within a region, as well as countries of origin that send migrants to the same countries of destination must share this data to formulate policies that serve a regional development agenda. This can go a long way in assessing capabilities and needs of communities at a regional level rather than just at national levels. Towards this end, these governments should come to data-sharing agreements that adhere to the best standards of data governance. The G20 can play a vital role in being a mediator at this stage it can ensure smooth and constructive dialogue and negotiations between national governments and provide guidelines and regulations on data sharing and data use.

4. Invest in strategic infrastructure both for local economic activity and future migration

Building basic infrastructure for production, trade and the mobility of people takes considerable time and resources. Governments must be committed to their new developmental path and must prioritise investments in infrastructures that materialise the movement of goods and people, such as transportation hubs and distribution facilities. Combining efficient transportation infrastructures with the deep networks and the able and flexible workforce of the return migrant community will ensure that the economy remains competitive and adaptable. To implement this effectively, governments can form public-private partnerships with the return migrant community. Towards this end, governments can also support the setting up of private enterprises by returnees according to their needs and assets assessed as described earlier in this brief. The recommendation to create separate departments or ministries mentioned above will also aid in improving related administrative and bureaucratic procedures.

5. Incentivise individual investment and engagement

Governments must adopt schemes that incentivise investments by returnees. They are partners in the new developmental policy, and measures must be adopted to maximise involvement and engagement in the origin countries. For example, regulators in Japan are providing incentives (in the form of subsidies worth USD 2.2 billion) to Japanese manufacturers to move production back to Japan (Business Today, 2020).

6. Weave a developmental vision that gains the support of the general public

Finally, governments must advance a developmental vision that is not only viable but also receives the energetic participation of the general public. Governments must promote a narrative of cooperation and engagement with the return migrant community, emphasise their centrality in the new developmental path, and foster a shared sense of accomplishment and destination.

ROLE OF THE G20

The G20, as a multilateral organisation of both developed and developing nations, is perfectly positioned to bring together countries of destination and countries of origin to mutually solve these challenges. The G20 can be a forum to discuss these challenges and establish standards and best practices to formulate policies that will naturally be different for different countries and regions not only because the challenges, strengths and developmental paths of regions vary, but also particularly because migration is a complex phenomenon that requires nuanced and targeted measures. The G20 can also be a stage to disseminate the stories of success and caution that will go a long way towards replicating successes and minimising mistakes.

CASE STUDY KERALA, INDIA

The state of Kerala in the southern part of India provides an interesting case study on the migrant and return migrant community. The state has a long history of international migration to the six Gulf Cooperation Council countries of Saudi Arabi, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Kerala has an expatriate population of 2.1 million (Rajan and Zachariah, 2019). Between the first week of May 2020 and 4 January 2021, 0.8 million migrants returned to Kerala (NORKA, 2021). Among them, 0.55 million reported that they had lost their jobs and 0.2 million that their visas had expired (ibid.).

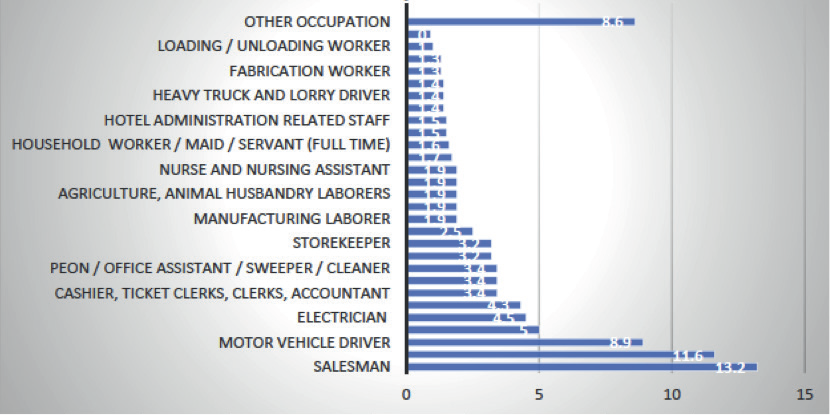

This could lead to Kerala facing long-term economic woe as the state is heavily dependent on remittances. Remittances account for over 30 percent of the state’s GDP, and one in three individuals in the state directly depends on them (Rajan and Zachariah, 2019). Kerala is also a good example to demonstrate the developmental value of the return migrant community. Presently, non-resident Indian bank deposits stand at over USD 25 billion in Kerala (PTI, 2021), and the occupations of return migrants include a wide range of low, semi-skilled and skilled ones (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage Distribution of Return Migrant Occupations

Source: Kerala Migration Survey 2018

Kerala is a good illustration of the value of good data sources in the implementation of governmental policies mentioned in this brief. The Kerala Migration Surveys that have been running periodically (every five years) since 1998 provide a wealth of knowledge on return migrants. The currently ongoing COVID-19 Return Migrant Survey, which will be completed shortly, has relevant data on the pandemic. It is the availability of this periodical data on migration that allowed the state to be equipped to receive such a large volume of return migrants and be one of the first states in the country to voice the concerns of the migrant community and express its willingness to work for their repatriation. Specific insights can be gained, hypotheses tested and interferences made using these rich data sources. The Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs (NORKA), a portfolio held by the Chief Minister of the state for over five years now, is a department which deals specifically with migrant issues including but not limited to recruitment of prospective migrants, training of both new and cyclical migrants, reintegration of return migrants and long-term planning related to migratory trends in the state. This department has funded data gathering and has used this data on migrants, return migrants, internal migrants and other socioeconomic and migratory trends for over two decades to formulate policies that have contributed to the economic well-being of the state, which has an otherwise weak industrial and manufacturing base. Remittances to the state have acted as a major catalyst in reducing poverty in the state and the contributions of migrants and return migrants have been vital to rural development as well as in socioeconomic and political development of the state through investments in micro, medium and small enterprises, the educational sector and the health sector.

1. Engaging with the return migrant community

The government of Kerala has always engaged with the return migrant community. At the state level, NORKAis a dedicated department that deals with migrant affairs. At the community level, the state has supported many organisations and self-help groups that directly or indirectly deal with migrant affairs. A classic example is Kudumbashree, a poverty eradication and women’s empowerment project.

2. Assess the needs and assets of return migrants

The government of Kerala, through NORKA and educational institutions such as the Centre for Development Studies (CDS) and the International Institute of Migration and Development (IIMAD) periodically surveys the entire geography of Kerala with a particular focus on migration and migration-related issues. Moreover, there are regular discussions held between the government, migrant associations and community leaders.

3. Data sharing between countries of origin in the region (and provincial governments within countries)

Although this is not directly applicable in this case, there is sharing of administrative, scholarly and aggregate institutional data (such as from the banking and transportation sectors) between government departments and research institutions. Additionally, Kerala Migration Survey (KMS) data is publicly available to the research community.

4. Invest in strategic infrastructure both for local economic activity and future migration

There are many policies of the Kerala government that foster economic activity among migrants, return migrants and prospective migrants. Kerala, although a small state compared to most others in India, has four international airports that cater predominantly to the migrant population. There is good road connectivity between the major cities and airports. The Additional Skill Acquisition Programme aims to increase the human capital of the populace by providing short-term skill development courses with an aim towards capturing the international labour market. There are also specific training programmes for migrants that sensitise them towards their rights and responsibilities. Most importantly, representatives from NORKA are designated as members of the State Planning Board to bring in migrant issues that are considered vital to long-term economic planning in the state.

5. Incentivise individual investment and engagement

The government of Kerala has multiple schemes which subsidise loans for return migrants. This has helped many return migrants start their own entrepreneurial ventures in the state. CDS, along with Central Michigan University, is also currently conducting a randomised control experiment to determine the best subsidies and intervention measures to be provided to return migrants to increase local investment and employment.

6. Weave a developmental vision that gains the support of the general public

Although this has not been a priority so far for Kerala, it is rapidly changing. This is reflected in the department of NORKA being handled by the Chief Minister. The general public is being made aware of the rewards and challenges of migration in the 21st century through press conferences and the media. There are more frequent visits by government authorities to Gulf Cooperation Council countries with the aim of uniting the migrant community working in different countries.

REFERENCES

Banco de Mexico (2021), Economic Information System: Remittance Income, https://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultarDirectorioInternetAction.do?accion=consultarCuadro&idCuadro=CE100&locale=en

Business Today (2020), “Coronavirus Impact: Japan to Offer $2.2 Billion to Firms Shifting Production out of China”, in Business Today, 10 April, https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/world/story/coronavirus-impact-japan-to-offer-22-billionto-firms-shifting-production-out-of-china-254367-2020-04-10

Capgemini Research Institute (2020), Fast Forward: Rethinking Supply Chain Resilience for a Post-COVID-19 World

Department of Non-Resident Keralite Affairs (NORKA) (2021), Government of Kerala, https://kerala.gov.in/non-residentkeralites-affairs-department

DilipRatha, Supriyo De; Eung Ju Kim; Sonia Plaza; Ganesh Seshan; and Nadege Desiree Yameogo (2019), “Data Release: Remittances to Low- and Middle-Income Countries on Track to Reach $551 Billion an 2019 and $597 Billion by 2021”, in People Move, World Bank Blogs, 16 October, https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/data-release-remittances-low-and-middle-income-countries-track-reach-551-billion-2019

DilipRatha, Supriyo De; Eung Ju Kim; Sonia Plaza; Ganesh Seshan; and Nadege Desiree Yameogo (2020a), Migration and Development Brief 32: COVID-19 Crisis through a Migration Lens, KNOMAD-World Bank, Washington, DC, p.8, https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/R8_Migration&Remittances_brief32.pdf

DilipRatha, Supriyo De; Eung Ju Kim; Sonia Plaza; Ganesh Seshan; and Nadege Desiree Yameogo (2020b), Migration and Development Brief 33: Phase II: COVID-19 Crisis through a Migration Lens, KNOMAD-World Bank, Washington, DC, p.7, https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/Migration%20&%20Development_Brief%2033.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2021), Return of Undocumented Afghans: Weekly Situation Reports, https://afghanistan.iom.int/pakistan-returns

Migration Data Portal (2021), Immigration and Emigration Statistics: Migration Data Relevant for the Covid-19 Pandemic, 10 March, https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/migration-data-relevant-covid-19-pandemic

Ministry of Civil Aviation, Government of India (2021), Vande Bharat Mission – Arrivals, https://www.civilaviation.gov.in

Nepal Rastra Bank(2021), Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation of Nepal, https://www.nrb.org.np/contents/uploads/2021/02/Current-Macroeconomic-andFinancial-Situation-Nepali-Based-on-SixMonths-data-2020.21-1.pdf

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)(2020), “News Release: Record Fall in G20 GDP in First Quarter of 2020”, 11 June, https://www.oecd.org/sdd/na/g20-gdpgrowth-Q1-2020.pdf

Press Trust of India (PTI) (2021), “Kerala: Allaying fears, Non-resident Keralites Send in Rs 18,749 Crore in Pandemic Year”, in Financial Express, 15 February, https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/kerala-allaying-fears-non-resident-keralites-send-in-rs-18749-crore-more-in-pandemic-year/2195429/

Rajan, S. Irudaya; and K.C. Zachariah (2019), “Emigration and Remittances: New Evidences from the Kerala Migration Survey 2018”,Centre for Development StudiesWorking Papers, No.483, Trivandrum

State Bank of Pakistan, External Relations Department (2020), Workers’ Remittances Rise to Record Monthly High in July 2020, https://www.sbp.org.pk/press/2020/Pr-17-Aug-20.pdf

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020), International Migration 2020 Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/452), p.16,

World Bank (2020), COVID-19 to Plunge Global Economy into Worst Recession Since World War II, 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/06/08/covid-19-to-plunge-global-economy-intoworst-recession-since-world-war-ii