The pandemic has taken a heavy toll on the global economy. The sources of economic growth and productivity gains have been constrained, and poverty and inequality have risen sharply. In addition, fiscal space has been severely reduced and public debt levels have risen at an unprecedented speed.

To accelerate the recovery from COVID-19 and make it more sustainable, it is urgent to reconsider debt-restructuring strategies. This policy brief describes the pitfalls in current approaches to debt restructuring for assessing sustainability in low and lower-middle income countries, proposes a reframing of debt sustainability analysis to take into account social and environmental sustainability and provides concrete examples of initiatives based on the experiences and challenges of the developing world.

Challenge

The pandemic dealt a severe blow to the global economy. Economic growth was abruptly cut across the world, with particularly strong impacts on the incomes of middle- and lower-income people.

Governments reacted quickly with aggressive fiscal and monetary measures. As a result of the former, public sector debt levels grew at a rate seldom seen – probably since World War II (IMF, 2022).

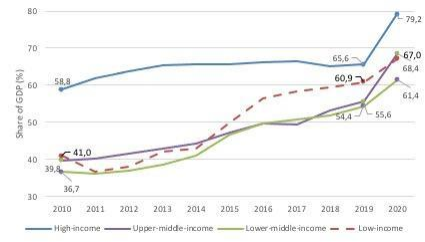

For middle-income and low-income countries, this growth in debt levels occurred at a time of high financial fragility. In previous years, low international interest rates and the massive search for yield strategies of the international financial system had led to a sharp increase in external obligations, particularly through the bond market (see Figure 1). The war in Ukraine only aggravates the outlook for debt in this group of countries.

Figure 1: Central government debt to GDP

Source: WDR 2022

This outlook of debt distress is happening at a time when governments in low and lower-middle income countries are in search of fiscal space to achieve the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs), strengthen health systems, accelerate the recovery and in many cases also addressing the growing impacts of climate change.

The relief, restructuring and reprofiling of public debt in troubled countries – with their associated conditionalities- will be a key element in determining whether the

The global economy will recover in an inclusive way or if poorer countries will lag even further behind.

At a global level, the current framework for dealing with distressed countries, first the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which expired in December 2021 and then the Common Framework for Debt Treatments, needs to be reinforced in the years to come. A new paradigm for fiscal and debt policies for lower-income countries, shared by creditors, debtors and international institutions, is needed.

Proposal

Debt-restructuring processes, with their associated conditionalities, are aimed at helping distressed economies to return to a sustainable path of macroeconomic stability and economic growth.

Of course, the way in which “sustainability” is defined is key to determining the set of policies to be implemented under a debt-restructuring agreement.

If the definition is limited to public sector finances, then the debt and fiscal policy framework should aim to create the necessary resources to normalise external payments as quickly as possible. The debt-sustainability approach of the multilateral lending institutions falls into this category, which means that in practice the majority of countries under debt stress often implement macroeconomic policy frameworks that land a disproportionate share of the burden of the needed fiscal consolidation on those with less voice in the society, such as women and the youth, or future generations. Consequently, public investment and education spending are often prime candidates for initiating fiscal-consolidation paths in these situations.

We propose to broaden the definition of sustainability to go beyond short-term government finance. This version of “sustainability” incorporates concepts associated with intra-generational equity (e.g. poverty and distribution) and inter-generational equity (e.g. climate and the environment), If, as proposed in this policy brief, a broader definition of sustainability is taken, then it is possible to find common grounds between the goals of development finance and fiscal -sustainability finance, and also uncover the necessary trade-offs.

A broad approach is very much in need in the developing world. It is particularly important for low and lower-middle income countries to integrate policies for debt management, short-run macroeconomic stability and the achievement of the SDGs and climate goals.

Finding the optimal framework for studying the sustainability of the poorest countries is a long process, very intensive both in international coordination and in the study of the specific contexts of each country. However, some progress has been made in this direction, although it has not yet taken center stage in the international discussion. In what follows we mention a set of proposals that are under discussion in the developing world, and that could take a more prominent place in the discussion on debt restructuring in a post-COVID world. It is based on the findings of a multiregional project on debt sustainability in low and lower -middle income countries with Canada’s International Development Research Centre’s (IDRC) funding.

Debt-for-climate swaps. These mechanisms consist of bilateral or multilateral debt being forgiven by creditors in exchange for a commitment by the debtor to use outstanding debt service payments for national climate action programmes. As we mentioned before, several low and middle-income countries are now on an unsustainable debt path as the external debt stock of both country groupings has risen by 5.3 percent to US$8.7 trillion (World Bank, 2021). At the same time, there are also ongoing climate and development crises. Increasing temperatures, rising sea levels and the attendant flooding, and extreme weather conditions indicate countries’ vulnerability to climate change. The situation requires a growing urgency for action but at the same time, it presents a dilemma. While significant finance is required to reverse the trends currently being experienced in climate and development outcomes, the impending debt crisis allows for limited liquidity to be deployed towards financing development priorities. However, innovations such as debt-for-climate and development swaps, that is, exchanging debt service payments with an obligation to channel funds towards climate and nature as well as gender outcomes, could create a win-win situation for both the debt, and climate and development crises. More specifically, debt swaps can be helpful in increasing resources for the government budget level or beyond; attracting more resources to the sectors targeted by the debt swaps; relieving debt burden; and synergising with government systems and policies.

Green tax reforms. Green fiscal tax reforms are a fundamental component of the transition to a sustainable development path and represent an intelligent fiscal measure with multiple positive effects. These reforms will contribute to controlling several negative externalities such as atmospheric pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and at the same time generate additional resources to support an expanding fiscal policy, promote structural transformations in the production and consumption patterns consistent with a low-carbon and inclusive economy and environment preservation and includes positive effects in employment, output, income distribution and poverty, gender, climate change and other SDGs.

The green fiscal policy will contribute to abandoning traditional fiscal-recovery strategies and consider new fiscal paradigms. The urgency and magnitude of the expenses to construct neutral carbon economies by 2050-2070, to achieve the SDGs by 2030 and to address the post-COVID-19 economic recovery require new fiscal and public debt-management strategies. It is not enough to consider additional expenses, for example to address the climate change challenge but a whole structural transformation of the fiscal policy. For example, it is indispensable to consider public expenses to support the construction of a social infrastructure for universal social-protection systems and universal child care. These policies have multiple benefits as they contribute to the welfare of the population, to the fiscal recovery and, moreover, can support the reduction of gender gaps as they offer women better conditions to incorporate into the formal labor market. Additionally, it is necessary that public investment is consistent with the objective of carbon neutrality; it is not possible to invest in fossil fuels and then consider using filters to reduce GHG emissions. Also, it is important to consider the potential consequences of the configuration of a high stranded assets risk.

All this requires a new public-debt management consistent with the construction of a new development path. This implies the incorporation of new tools for risk administration to climate, natural disaster and other macroeconomic shocks and the promotion of new finance sources such as green, sustainable or gender bonds with better financial conditions and that offer conditional payments in relation to the advance of climate change and other social targets.

Non-regressive tax reforms for debt reduction. The available evidence in low and lower-income countries shows significant distributional effects of increasing the tax rate to reduce debt. More specifically, an increase in the tax rate is associated with an increase in inequality, declines in wage income and in the wage share of income, and increases in long-term unemployment.

Consumption taxes are relatively efficient in reducing the short to long term debt ratio when compared with income and corporate tax rates. However, consumption taxes also wipe out the fiscal gains through a decline in output. The adverse effects of consumption tax increases is typical if fiscal authorities engage in repeated rounds of tax rate hikes in an effort to get the debt ratio to converge to the official target. For Uganda, for example, rapid fiscal consolidation may exacerbate poverty especially in the lagging regions of eastern and northern Uganda (Lakuma, 2018).

However, whether fiscal consolidation will achieve its objectives of reducing debt, while maintaining the same level of welfare will depend on how the burdens of taxation and the benefits of social spending are distributed. One way is to differentiate the consumption taxes by retaining the current rate for durable and nondurables consumed by the poor and adjusting the rate upwards for those consumed by the non-poor. This ensures that the poor are shielded from the adverse effect of a tax increase as the government reduces its debt ratio.

References

IMF; Making Debt Work for Development and Macroeconomic Stability, Series: Policy Paper No. 2022/019, April 26, 2022, retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2022/04/26/Making-Debt Work-For-Development-and-Macroeconomic-Stability-517258

Lakuma, Corti Paul; Mawejje, Joseph; Lwanga, Musa Mayanja; Munyambonera, Ezra; The distributional impacts of fiscal consolidation in Uganda. June 29, 2018, retrieved from: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US2022218793

World Bank:

Low-Income Country Debt Rises to Record $860 Billion in 2020. Oct. 11, 2021, retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/10/11/low income-country-debt-rises-to-record-860-billion-in-2020

Finance of Equitable Recovery. World Development Flagship Report, 2022, retrieved from:

https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2022