Infrastructure projects are a strategy for growth used worldwide. Despite high levels of global savings, financing gaps in infrastructure development continue to exist. This gap is in large part the result of inadequate policies and processes. Issues with infrastructure project pipelines, governance, national budget commitments, land use, and sustainability costs are important factors that inhibit domestic and global capital flows into infrastructure projects. Multilateral cooperation among governments and development banks can facilitate an environment where policy, regulation, market, and capacity elements support capital investments. The Group of Twenty (G20) can take the lead in supporting such multilateral cooperation through a framework that connects initiatives in finance, multilateralism, trade, and infrastructure tracks in the G20 process.

Challenge

Infrastructure projects are an international strategy for growth and bring high rewards and innovation into different sectors of an economy. These are recognized pathways for narrowing development gaps among regions and raise the development indices of vast numbers of people. Quality infrastructure—whether related to transport, water, energy, digital, or social ties—is indispensable for the achievement of the Agenda 2030 and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Investing in infrastructure helps integrate national markets and provides connections to global value chains. Infrastructure growth is trade-enhancing and enables direct investments into countries.

Planned infrastructure development improves the productive potential of the economy but requires careful calibration of cost and benefit, quality infrastructure, land acquisition, sustainable financing, and project transparency. Regulatory policies and capacity issues also need to be considered. Promoters of infrastructure projects and prospective investors are usually left on their own to achieve this objective and resolve the difficult triad of attracting investments that promise returns, project governance, and sustainability.

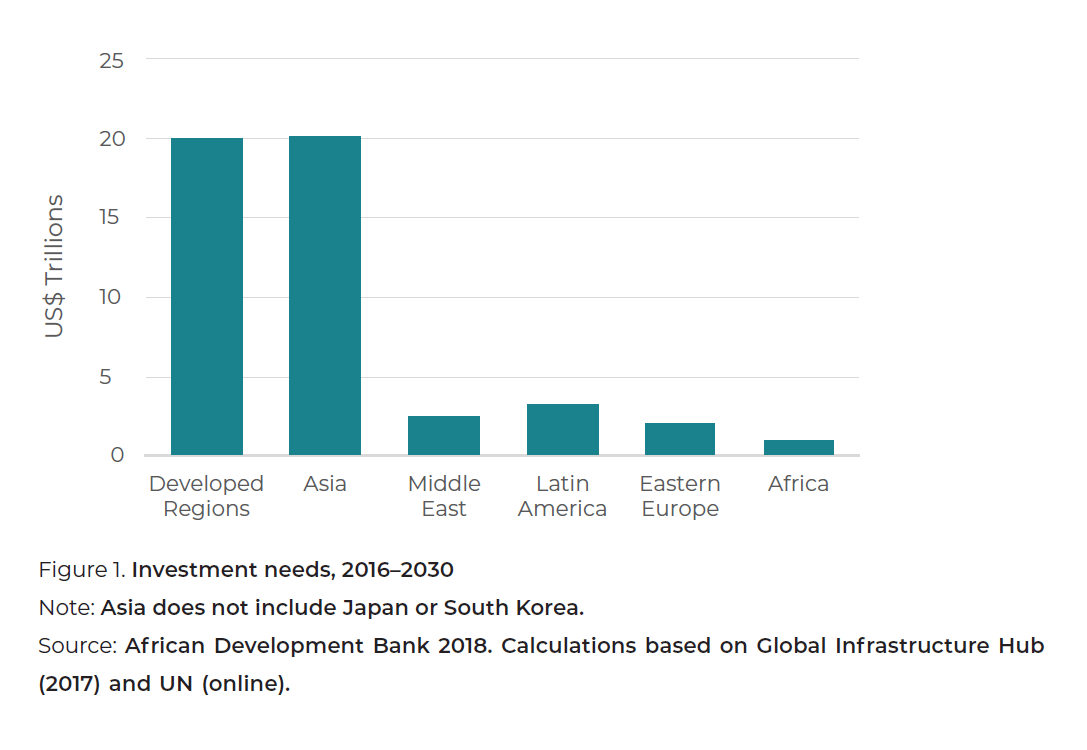

The global demand for infrastructure far outstrips the pace of infrastructure development. From 2015 to 2030, global demand for new infrastructure could amount to more than $90 trillion. Current infrastructure spending of $2.5 to $3 trillion a year is only half the amount needed to meet the estimated $6 trillion of average annual demand over the next 15 years (Bielenberg et al. 2016). The development paradox here is that institutional investors such as insurance companies, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds have more than $100 trillion in assets under management globally.

Crucial infrastructure could allow vast areas of Asia and Africa to realize their demographic dividend and economic potential. However, mobilizing the necessary infrastructure-related resources is difficult because of inadequate addressing of project preparation, implementation, maintenance, sustainability, and capacity details. Despite availability of policy guidance from the Group of Twenty (G20), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), multilateral development banks, and other stakeholders, several infrastructure plans across Asia and Africa are unable to take off, delayed, or unsustainable. Geopolitical rivalry over infrastructure projects and finances is also an impediment and is, in fact, making institutional investors more cautious.

Despite available policy guidance, mobilizing funds for infrastructure requires a predictable, informed, and facilitative environment. This policy brief proposes a multilateral cooperation model endorsed by the G20 to overcome the underlying causes of financing gaps for infrastructure investments in Asia and Africa and facilitate global investment in infrastructure.

Proposal

Planned infrastructure development can positively exploit the diversity among countries and sub-regions and narrow development gaps. Several guidelines have been designed to support governments and financial institutions toward meeting the global standards of governance, sustainability, and investment pathways. These include the G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment and Principles for Project Preparation and the OECD Principles for Private Sector Participation in Infrastructure. A multilateral cooperation model endorsed by the G20 can provide a predictable, informed, and facilitative environment for mobilizing funds and connecting the governance, sustainability, and investment pathways. This model should include the following:

- Investment facilitation for infrastructure projects can reduce the asymmetry of information, simplify governance, harmonize regulatory processes, and minimize risks on returns.

- Multilateral cooperation for facilitating investment in infrastructure is an urgent need.

- Financing can be mobilized through multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation.

- Multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation will link the needs of investors, governments, and people and mobilize global funds.

- Some initiatives on multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation in infrastructure are noteworthy.

Investment facilitation for infrastructure projects can reduce the asymmetry of information, simplify governance, harmonize regulatory processes, and minimize the risks on returns

Even though private investors, including institutional ones, have about $120 trillion in global assets under management, investments in infrastructure are not forthcoming. Several studies have clarified the reasons for financial gaps between the demand and supply of capital for infrastructure development. Given this availability of capital on one side and lack of investments on the other, an analogy from trade facilitation can be drawn and applied to infrastructure investment. Trade facilitation measures expediting the movement, release, and clearance of goods, including goods in transit. It also includes measures for effective cooperation between regulatory authorities on facilitation and compliance issues. Technical assistance and capacity building are essential for a successful facilitation among developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs). Importantly, trade facilitation is always more successful as a multilateral platform that benefits all stakeholders—investors, recipients, goods and service providers, and people—to maximize their objectives.

Multilateral cooperation for facilitating investment in infrastructure is an urgent need

(a) Mobilizing finance for infrastructure is the foremost concern

Infrastructure development has not kept pace with the corresponding demand. Bielenberg et al. (2016) estimated the value of the world’s existing infrastructure at $50 trillion, and the global demand for new infrastructure up to 2030 could amount to more than $90 trillion. Current infrastructure spending of $2.5 to $3 trillion a year is only half the amount needed to meet the estimated $6 trillion of average annual demand over the next 10 years. More than 60% of this financing gap is likely to be concentrated in middle-income countries, with more than 50% in the power sector. Given this large demand, capital markets will be pivotal to financing investment, particularly the banks, pensions, and insurance companies that hold more than 80% of institutional assets under management (AUM) in middle-income countries (Bielenberg et al. 2016).

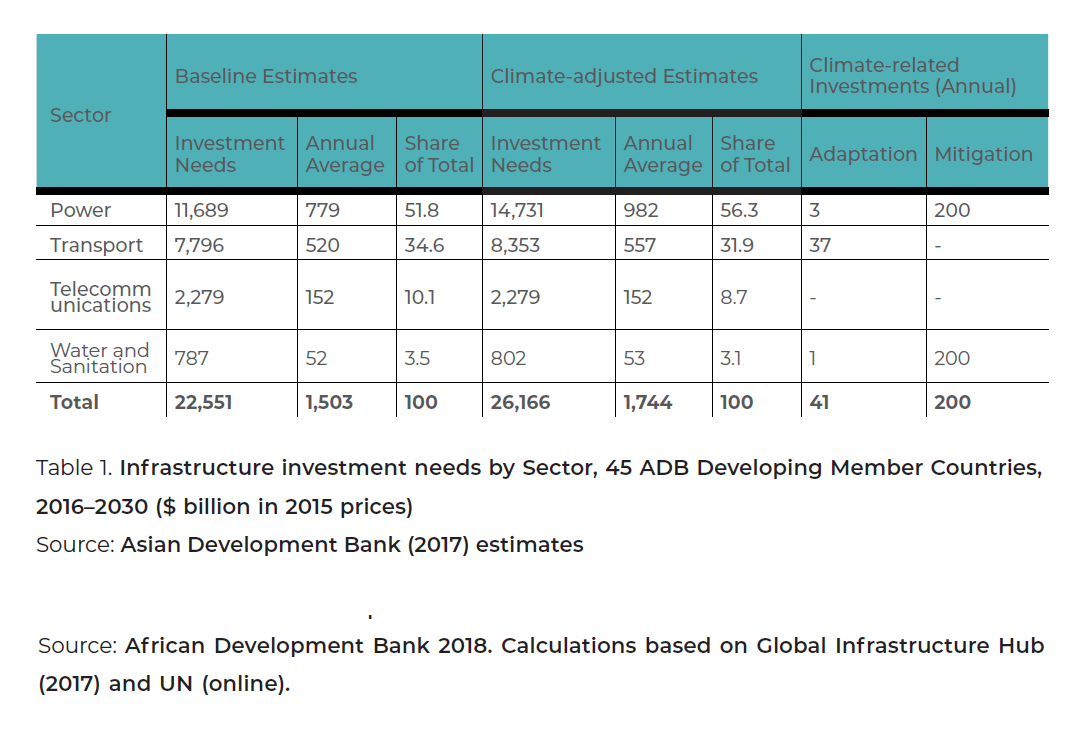

Asia is one of the most dynamic and productive regions, but it is restrained from realizing its full potential by huge constraints in crucial infrastructure caused by a lack of investment. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has estimated that Asia will need to invest $26 trillion for infrastructure from 2016 to 2030, or $1.7 trillion per year. This would allow the region to maintain its growth momentum, eradicate poverty, and respond to climate change. Without climate change mitigation and adaptation costs, $22.6 trillion, or $1.5 trillion per year, will be needed (ADB 2017).

Infrastructure investment varies considerably by sector (Table 1). The power and transport sectors require the largest investments, and telecommunications and water and sanitation are no less important for an economy or for individual welfare, and therefore require investment. Each of these sectors has varying levels of regulatory, governance, and sustainability challenges in different countries.

Africa’s infrastructure requirements are also immense. One of the key factors retarding industrialization has been the insufficient stock of productive infrastructure in power, water, and transport services that would allow firms to thrive in industries with strong comparative advantages. New estimates by the African Development Bank (AfDB) suggest that the continent’s infrastructure needs amount to $130–$170 billion a year, with a financing gap ranging $68–$108 billion (AfDB 2018).

Global funds are available for investment. A small fraction of the more than $100 trillion in assets managed globally and low-yield resources would be enough to plug the financing gap, and finance productive and profitable infrastructure. Issues of infrastructure project pipelines, feasibility assessments, and national budget commitments are important factors that inhibit domestic and global savings from being directed to infrastructure projects.

(b) Financing of infrastructure plans creates competing interests among countries Infrastructure initiatives are the new geopolitical tools, creating new rivalries or prompting the re-emergence of old ones (Islam, Rohde, and Chawla 2019).

China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has helped bridge the infrastructure investment gap. However, it has also increased geo-economic tensions and competitive plans.

Infrastructure development within and outside domestic borders is noticeable in other important economies. Japan, India, and Europe, as well as Russia, the United States, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN), are working hard to further their own connectivity agendas in Asia and Africa.

The contours of the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC; Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2016), BRI, Asia Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), and European Union (EU)-Asia connectivity, to name a few, are different in terms of their origins, partnerships, resources, and the political and economic priorities of the promoters (see Appendix). Prakash (2020) conducted a comparative study of these important connectivity plans in Asia in “Rethinking Global Governance.” The ASEAN approach to connectivity aims for a resilient and integrated ASEAN community. The BRI has strong financial resource commitments from China and aims to establish multitiered connectivity networks among the Asian, European, and African continents and their adjacent seas and strengthen “Belt and Road” country partnerships. Supported by India, Japan, and many African and Asian countries, the AAGC aims for Africa’s integration with Asia through physical, institutional, and social connectivity in which quality infrastructure, trade, institutional connectivity, and enhanced capacities and skills are important pillars. The EU-Asia connectivity plans are building blocks toward an “EU Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia” with concrete policy proposals and initiatives, including through interoperable transport, energy, and digital networks. The strategy seeks to ensure sustainable, comprehensive, and rules-based connectivity between Europe and Asia. In a global milieu, all these plans are competing for space, resources, influence, and results. A multilateral cooperation process for investment facilitation could reduce multiplicity and create synergy and common purpose among different infrastructure plans. The multilateral cooperation framework would promote and build transparency among competing initiatives and allow investors to make informed decisions.

(c) Governance and sustainability increase cost but are important for attracting financing from financial institutions

The financing gap for infrastructure is, in large part, the result of inadequate policies and processes and a lack of familiarity with projects. Governments play a central role in most infrastructure projects because infrastructure has strong public-good characteristics, requires large-scale capital mobilization, and is highly sensitive to local politics. However, the scale of infrastructure spending required over the next 10– 15 years, coupled with widespread public-sector fiscal constraints, means that private finance will be increasingly important. A positive “enabling environment”—that is, one characterized by sound policies, effective institutions, transparency, reliable contract enforcement, and other sector-specific factors—makes it easier to mobilize private finance. Conversely, a poor enabling environment—one characterized by distorting subsidies, unreliable counterparties, and flawed procurement processes—can raise the cost of private finance to the point where infrastructure projects are no longer economically viable (Bielenberg et al. 2016).

Trans-regional plans such as BRI, AAGC, MPAC, and EU-Asia connectivity are seeking greater emphasis on governance, standards, transparency, and sustainability in varying degrees. Institutions such as the Asian Development Bank Institute and the AfDB have helped to further this objective by providing climate adaptation and mitigation adjusted costs for infrastructure. Transparency in project preparation and accountability in project execution are important global concerns emerging from the financing and implementation of infrastructure plans. Global attention has been drawn toward issues of planning and project design, financing and debt sustainability, territorial integrity, and people’s choices.

Financing can be mobilized through multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation

Financing infrastructure projects that ensure returns, have sound project governance, and comply with sustainability checks require fund mobilization from new sources. A greater crossholding of interest among all stakeholders is important to achieve this. A multilateral cooperation framework among governments, supported by the multilateral development banks (MDBs) would help streamline the policies related to cost subsidy, regulations for procurement, information on contract enforcement and dispute redressal, and other similar market and capacity elements that are crucial for facilitating investments.

Multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation has a specific role in removing the barriers to the funding of projects. These barriers to fund mobilization are well known by agencies, but surprisingly, are not being addressed enough in policy and practice, as in the following:

- Long-term plans for infrastructure (pipeline projects) are either unknown or may not be well communicated by governments, making it difficult for institutions to consider investing in evaluations and committing resources for those countries or sectors.

- Fragmented standards, diverse processes, and costs unique to a project deter prospective investors, especially those with limited resources, time, and expertise, such as pensions and insurance companies.

- Governance and sustainability incur higher upfront costs for the investor, while the savings accrue for the owner or the consumer of infrastructure projects.

- Acquisition of land for infrastructure development remains one of the major challenges.

- Private investment can help enhance the financial sustainability of infrastructure projects, but the private sector has different incentives from governments in relation to the development of projects. The private sector typically tends to cluster its investments around fast-developing growth centers, creating disparities in spatial development.

- Global financial regulations on investment limits, capital adequacy and reserve requirements from banks, and limits on foreign investment can discourage investors from making longer-term and cross-border investments. Basel III regulation and Solvency II directives are two such examples. Basel III regulation of banks’ capital, leverage, and liquidity makes it harder and more expensive for banks to issue longterm debt, such as project-finance loans. Solvency II directives are for the amount of capital that EU insurance companies must hold and treat long-term investments in infrastructure as of similar risk to long-term corporate debt or investments. Accounting standards of governments that do not differentiate between long-term investments that add value and near-term consumption are another example.

- Middle- and low-income countries face additional challenges due to the lack of project development resources and affording the funding commitments for guarantees to mitigate project risks.

Multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation can converge the difficult triad of investment in infrastructure projects

The G20 has already determined the general principles of multilateral cooperation for investment in infrastructure (see Appendix). These principles reflect the global consensus on quality infrastructure planning and investment but are voluntary in nature. Connecting the diverse requirements—or managing the difficult triad—of finances (investments and returns), governance (planning, implementation, and maintenance), and sustainability (environment, resilience, and inclusiveness) of infrastructure projects requires multilateral cooperation mechanisms to ensure prompt compliance. Collective decision-making is especially needed when an infrastructure scheme spans national boundaries and the alignment of cost and benefits may be contested (Hawke and Prakash 2016).

Funding infrastructure around the world should not be an issue when financial resources are available. Apart from the public sector and central banks in advanced economies, institutional investors such as insurance companies, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds have around $100 trillion in AUM globally (Arezki et al. 2017). Mobilizing these finances for investment in infrastructure is the key issue. There are institutional issues, too, arising from managing the interaction of international pressures on national autonomy. There are practical aspects of unified or common regime for the movement of goods, services, and people. The governance mechanisms and standards would also include technical specifications, safety management frameworks, social and economic well-being of workers in the sector, competition policy, customs cooperation, and the like (Prakash 2020).

With governments as the main drivers of multilateral cooperation, the critical role for MDBs and other development finance institutions (DFIs) in blending public and private finance to scale up financing for infrastructure will be important. The Hamburg Principles have welcomed the role of the MDBs in mobilizing and catalyzing private capital and endorsed a target of increasing mobilization by 25% to 35% by 2020 (AfDB et al. 2018).

Multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation will converge the needs of investors, governments, and people and mobilize global funds

A multilateral cooperation program among countries and MDBs could facilitate global investment in infrastructure by creating more efficient, informed, transparent, and predictable investment conditions around infrastructure plans and projects. Development banks feature prominently in this multilateral cooperation because they have the mandate, motivation, and means to influence financing flows and shape markets and have experience in infrastructure funding that could help other actors, such as private-sector and institutional investors in taking on the projects. Such cooperation works best when undertaken at a regional level, as is seen in the case of connectivity infrastructure projects in Asia and Africa. This is also important because it is easier for policy makers to find synergies between national and regional development strategies. Some examples of this are projects such as BRI, AAGC, the Trilateral Highway, and the Greater Tumen Initiative. The cooperation however can extend to other regions too, as funds are expected to flow from near and far. The experience of members from other regions also matters. The measures undertaken for investment facilitation would include:

- Aggregation of information on pipelines of infrastructure projects in roads, railways, power interconnections and transmission lines, bridges, ports and airports, and information and communication technology networks that are at an advanced stage of project preparation, have relatively robust economic cases, and are likely to be able to substantially mitigate risks, including environmental and social (E&S) risks.

- Follow-up information on the pipeline of projects where the economic case is reasonably strong but may need further substantiation and/or have risks that appear to be manageable.

- Project-preparation facilities and technical assistance to increase the “bankability” of project pipelines.

- Improving regulatory transparency and predictability—such as publication/ notification of investment-related measures, enquiry points/single window.

- Streamlining and speeding up administrative procedures—such as the procedural aspects of investment applications, approval processes, licensing and qualifications, and formalities and documentation requirements—as one-stop shop/single window services.

- Enhancing international cooperation and addressing the needs of developing members—such as the exchange of information among competent authorities and technical assistance and capacity building for developing countries and LDCs.

- Other investment facilitation-related issues—such as government-investor cooperation, resolving investors’ grievances/ombudsperson, and corporate social responsibility.

- E&S assessments of projects.

- Mitigating infrastructure redundancy risk by offering an options analysis of competing projects.

- Debt sustainability and fiscal risk assessments of the projects.

- Transparency and competition in procuring the project.

- Regulatory transparency and harmonization, single window services, and streamlining of the procedural aspects of investment.

- Exchange of information among all members.

- Technical assistance and capacity building for developing countries and LDCs.

- Other facilitation-related issues—such as government-investor cooperation, and resolving investors’ grievances/ombudsperson.

Some initiatives on multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation in infrastructure are noteworthy

Some important initiatives of multilateral cooperation are already taking shape, and each is unique to the strengths and requirements of the members and partners. The Multilateral Cooperation Centre for Development Finance (MCDF) initiated by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the AAGC, and MPAC 2025 are following the multilateral or trilateral cooperation framework for all or some aspects of infrastructure financing, project preparation, information sharing, and capacity building.

Multilateral cooperation for investment facilitation will improve the speed, scale, and pricing with which private capital could flow into infrastructure investment. It will lead and complement the capital markets’ response toward infrastructure investments through streamlining of policy and regulatory rules, institutional conduct, and agency factors. Multilateral cooperation, supported by the G20 and other similar groups of economies, will encourage governments and MDBs to provide an informed, predictable, and transparent investment environment for institutional investors and get capital to flow into projects.

Relevance to the G20

The G20 is mandated to promote innovative mechanisms for cooperation and development. Different G20 tracks can be coordinated to form a coherent multilateral framework for facilitating investment in infrastructure:

- The G20 already encompasses member countries who are promoting several infrastructure and connectivity plans in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

- Important financial institutions in Asia, Europe, and Africa are also part of the G20 process.

- The G20 is committed to providing the ecology and platforms for multilateralism, innovative governance, and cooperation mechanisms.

- A multilateral cooperation program endorsed by the G20 among countries and MDBs could facilitate global investment in infrastructure by creating more efficient, informed, transparent, and predictable investment conditions around infrastructure plans and projects.

- The G20 has created several principles for promoting important dimensions of infrastructure development. It supports the enhanced role of MDBs and private funds. The Global Infrastructure Connectivity Alliance hosted by the World Bank is an important initiative for the monitoring of global infrastructure.

- The G20’s various initiatives in finance, multilateralism, trade, and infrastructure tracks can be placed under a multilateral cooperation framework for investment facilitation for infrastructure.

- The finance ministers meeting could steer the multilateral framework for facilitating investment in infrastructure. A regional approach to investment facilitation would be more practical.

- The multilateral cooperation framework will be the G20’s coordinated support to facilitate infrastructure investments.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

African Development Bank (AfDB). 2018. “Africa’s Infrastructure: Great Potential but Little Impact on Inclusive Growth.” In African Economic Outlook 2018, 63–94. African Development Bank. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/African_Economic_Outlook_2018_-_EN.pdf

African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure

Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector, Inter-American Development Bank, et al. 2018. Mobilization of Private Finance by Multilateral Development Banks and Development Finance Institutions. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/4366950e-b757-4190-8074-7db86e2860a7/201806_Mobilization-of-Private-Finance_v2.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mfmjKJZ

Arezki, Rabah, Patrick Bolton, Sanjay Peters, Frederic Sanama, and Joseph Stiglitz. 2017. “From Global Savings Glut to Financing Infrastructure.” Economic Policy 32, no. 90: 221–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eix005

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2017. Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs. Manila: ADB. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/227496/special-reportinfrastructure.pdf

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). 2019. Memorandum of Understanding on Collaboration on Matters to Establish the Multilateral Cooperation Center for Development Finance. Beijing: AIIB. https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/who-we-are/partnership/_download/collaboration-on-matters.pdf

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. 2016. Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025. Jakarta: ASEAN. https://asean.org/storage/2016/09/Master-Plan-on-ASEANConnectivity-20251.pdf

Bielenberg, Aaron, Mike Kerlin, Jeremy Oppenheim, and Melissa Roberts. 2016. Financing Change: How to Mobilize Private Sector Financing for Sustainable Infrastructure. McKinsey Center for Business and Environment. https://newclimateeconomy.report/workingpapers/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2016/04/Financing_change_How_to_mobilize_private-sector_financing_for_sustainable-_inf rastructure.pdf

Hawke, Gary, and Anita Prakash. 2016. “Conceptualising Asia Europe Connectivity: Imperatives, Current Status and Potential for ASEM.” In Asia–Europe Connectivity Vision 2025. Challenges and Opportunities, edited by Anita Prakash, 3–10. Jakarta: ERIA. https://www.eria.org/Asia_Europe_Connectivity_Vision_2025.pdf

Islam, Shada, Amanda Rohde, and Rahul Chawla. 2019. Connectivity Needs A Strong Rules-Based Multilateral Framework – For Everyone’s Sake. Brussels: Friends of Europe. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/insights/connectivity-needs-a-strongrules-based-multilateral-framework-for-everyones-sake

Prakash, Anita. 2020. “Connecting the Connectivities: It’s Time for Regional Initiatives to Work Together.” In Rethinking Global Governance, edited by Arnaud Bodet, Indrė Krivaitė, Zachary McGuinness, and Angela Pauly, 18–21. Brussels: Friends of Europe. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2019_FoE_AEE_AP_PUB_Global-governance.pdf