Despite the international consensus on the need to tackle illicit financial flows (IFFs), which materialized in the 2030 Agenda, the UN has not agreed on a method for keeping track of the issue. While the quantification of IFFs does not seem feasible, this paper argues that engagement against IFFs can easily be measured by drawing on official and reliable sources that assess countries against standards on which they have previously agreed. An example of such a measurement is provided by drawing on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) peer review system, and it is suggested that the G20 use this to fill in this global governance gap.

Challenge

Growing concern about IFFs and their negative impact on development materialized in the insertion of target 16.4 in the Sustainable Development Agenda. Framed under SDG 16 on Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, this target was defined as a significant reduction of illicit financial and arms flows. It was accompanied by indicators to guide the implementation and follow-up in these reductions. Indicator 16.4.2 on the seizure of arms of illicit origin was soon supported by a data collection method, and this has already been utilized in 66 countries. However, there is no agreement as yet on how to generate indicator 16.4.1, defined as the USD value of inward and outward IFFs.

Long before the UN took over leadership of this agenda, other international organizations, such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), mobilized international cooperation and academic research on the issue. In academic studies, we find two general approaches to measure the volume of IFFs at the national level: (1) estimates through capital flight and (2) macroeconomic and microeconomic estimates of IFFs. The former approach is based on the concept of capital evasion or money evading cross-border capital controls. The latter applies to money concealed from all manner of national authorities. It includes tax evasion as well as money flowing to or from criminal activities.

The following are the five techniques commonly used to measure IFFs:

(1) The Hot money method: based on the concept of capital flight, it measures shortterm export capital by financial institutions.

(2) The Residual approach: measurements are made based on the sum of the internal flows of net capital and the current account deficit less the increases in official foreign reserves.

(3) The Dooley method: measurements are carried out through the compensation of the assets in the market produced by non-residents that do not generate investment income and are reported in the balance of payments together with financial debt.

(4) False commercial invoicing: based upon underestimates of exports or imports in international trade information.

(5) IFFs: this combines the transfer pricing manipulation method in commerce with the hot money method or the residual method.

The techniques listed above have greatly contributed to raising awareness of the problem of IFFs. In the 1990s, Michel Camdessus gave momentum to international cooperation against money laundering by setting an experts’ consensus range of IFF estimates between 2% and 5% of global GDP (1998). More recently, Global Financial Integrity has quantified the illicit outflows from developing countries at USD 1 trillion, making a case for inserting IFFs in the development finance agenda (OECD 2014).[1] However, IFF metrics have attracted more critics than followers. Even thirty years after the establishment of the experts’ consensus range, no governmental or intergovernmental institution has adopted a method to measure this phenomenon systematically. IFFs are hidden by their very nature and are therefore difficult to measure (Cobham 2012).[2] Organizations operating illegally are not interested in sharing their information with governments, and governments that acquire such information from their intelligence agencies are not interested in its disclosure. By choosing such an ambitious indicator as the USD value of inward and outward IFFs to monitor (SDG 16.4.1), the UN has failed to improve countries’ commitments against IFFs.

Proposal

Countries’ efforts against IFFs are measurable

While the quantification of IFFs does not seem feasible, the engagement against IFFs can easily be measured by drawing on official and reliable sources that assess countries’ performance against standards on which they have previously agreed. According to the international consensus, the fight against hidden finance must be carried out using international financial transparency. This consists of governments obtaining financial information on citizens and businesses and exchanging that information with other governments. Intergovernmental institutions such as the domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project, FATF, and Global Forum on Information Exchange with Tax Purposes have adopted clear rules on how information must be obtained and shared.

These institutions not only set international standards but also monitor countries’ compliance using peer review mechanisms. The FATF has the longest-running mutual evaluation system, with four rounds of peer reviews over 30 years. Its assessments cover some of the Global Forum criteria, as well as many other aspects of financial transparency, and not only refers to tax evasion but also other predicative offenses such as drug trafficking, organized crime, corruption, and tax evasion. FATF assessments are prepared by a team normally comprising five expert advisers from member states and the FATF secretariat. A document review is conducted, as well as a country visit, a survey of the country under review and partner countries, and a discussion on the draft assessment between the assessors and the country under assessment. The reports are subject to quality control by the FATF secretariat and a plenary discussion behind closed doors. Once adopted, the application of the recommendations included in the evaluation report is monitored and may lead to monitoring reports modifying the initial assessment by the evaluation team.

Despite their robustness, little attention is paid to FATF reports by either political leaders or public opinion. Full of rich description and technical details, they lack synthetic scores that facilitate the understanding of each country’s performance and its comparison with other countries.

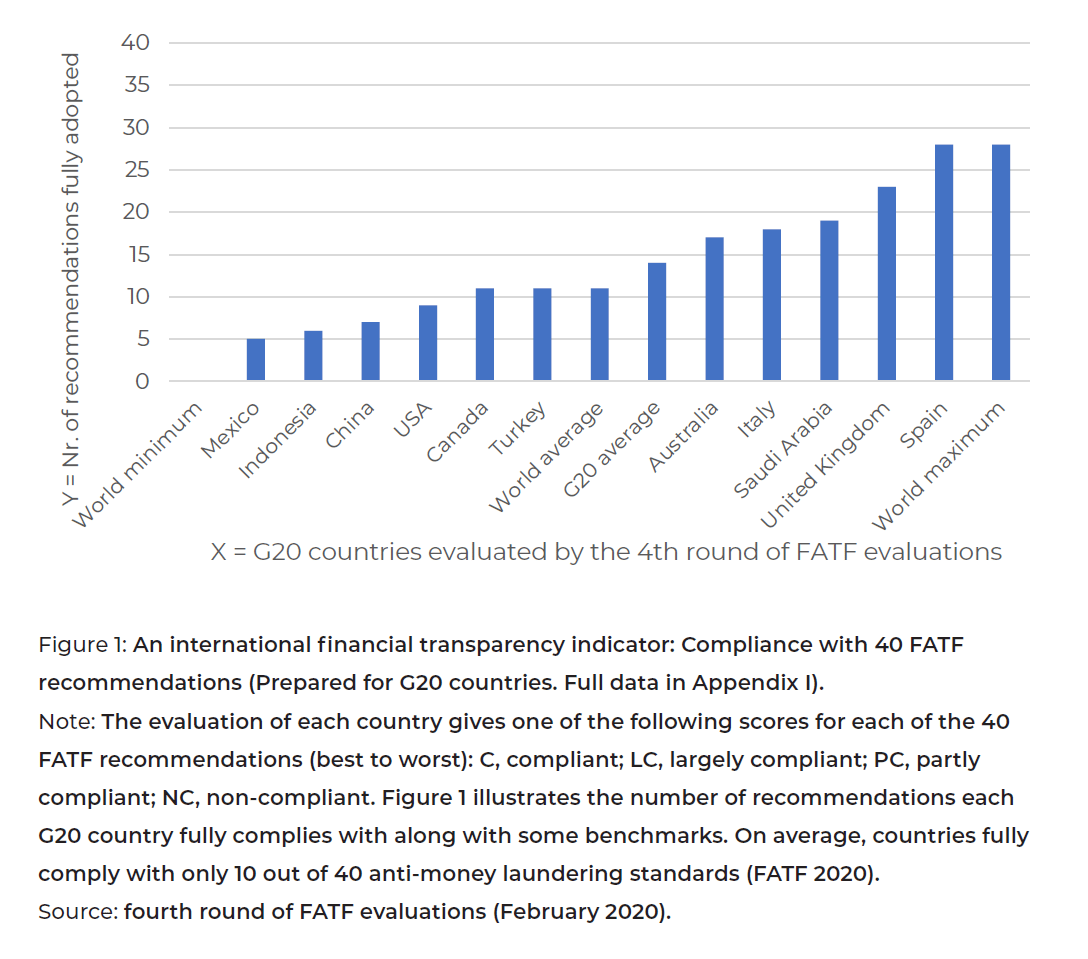

Nevertheless, FATF reports conclude by assessing each country’s application of each of the 40 recommendations as compliant, largely compliant, partly compliant, and non-compliant. Therefore, they pave the way for preparing a simple but meaningful indicator: the number of recommendations with which each country fully complies. Figure 1 illustrates the results of such an exercise drawing on the February 2020 data released by the FATF. It indicates that financial transparency standards are applied in a heterogeneous and rather loose manner, and therefore it is worth communicating and analyzing their development.[3]

The FATF mutual evaluation reports provide a variety of information to prepare more sophisticated indicators. The NGO Tax Justice Network (TJN) draws on several sections of these reports to produce the Financial Secrecy Index (TJN 2020).[4] However, the indicator presented in Figure 1 above will very likely have a higher acceptance among governments as it relies exclusively on data and definitions produced by an inter-governmental institution.[5]

It is worth noting that the FATF and many international organizations that generate an abundance of statistics are aware of how their findings can be used to “name and shame” the least compliant countries. However, for obvious reasons, their secretariats are reluctant to generate controversies around rankings with member states unless such rankings are requested by countries, or at least, by an influential group of countries. Subsequently, the G20 has a role to play in enforcing international agreements against IFFs.

The G20 has made several declarations against hidden finance and in favor of financial transparency. The most relevant ones are probably that of the G20 London Summit announcing the end of the tax haven era in April 2009, and the Tax Annex to the Saint Petersburg G20 Leaders’ Declaration launching the BEPS in 2013.

The value added by the G20 to the BEPS process through the Saint Petersburg declaration was clear and aligned with the comparative advantage of the G20 with regard to broader and more inclusive international settings. In that summit, the biggest world economies advanced an international agreement that would later be endorsed by 135 countries and supported by formal international organizations, such as the OECD.

The G20 provides additional support to international financial transparency initiatives through communiques following the meetings of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors. Under the Argentinian presidency in 2018, for instance, a G20 communique highlighted the individual and collective commitment of member countries to the full and effective implementation of the FATF standards. It recognized the urgent need to clarify how they apply to virtual currency providers and related businesses. The meeting also insisted on the need to implement the BEPS package worldwide and to sign and ratify the multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters. It welcomed the commencement of the automatic exchange of financial account information and the adoption of some of the criteria by the OECD to identify opaque jurisdictions that have not satisfactorily implemented tax transparency standards. In 2019, under the Japanese presidency, these statements were reiterated, and further support was provided to the FATF by welcoming its ongoing strategic review. The United Nations Security Council Resolution 2462 stresses the essential role of the FATF in setting global standards for preventing and combatting money laundering. More recently, in February 2020, the G20 gathered in Riyadh expressed its concern about the money laundering risks arising from financial innovations. They supported the FATF statement on the applicability of its standards to virtual assets and related providers.

Unlike the St Petersburg declaration, the relevance and effectiveness of these communiques are not clear. They simply reiterate the G20’s support for the standards set in institutions in which the G20 member states are represented along with many other countries. The influence of the biggest economies’ Finance Ministers and Central Governors, along with all the stakeholders mobilized around G20 meetings, could be more effectively used if reoriented toward compliance with international standards. In other words, G20 communiques and preparatory reports, such as the one submitted to the G20 by the FATF annually, could be used to provide indicators like those listed in Figure 1. Ideally, G20 countries could also improve their indicator scores.

Recommendations

Based on the above analysis, three recommendations can be provided to the G20 and its member states to increase the effectiveness of international standards on financial transparency:

1. Shift the focus of international monitoring initiatives from IFFs to financial transparency.

IFFs are hidden by nature and are therefore difficult to measure. The introduction of the concept of IFFs in the post-2015 process was instrumental in raising international awareness of the issue and including it in the 2030 Agenda. However, it has led the UN to an impasse regarding the preparation of an indicator on a country’s progress in this area.

While the world has not yet agreed on how to monitor progress against IFFs, there is a consensus on the way such progress might be achieved. The fight against hidden finance must be carried out utilizing international financial transparency. This consists of governments obtaining financial information on citizens and businesses and exchanging that information with other governments, following internationally agreed standards. It is therefore suggested that countries’ accountability with regards to IFFs be increased by measuring the degree of compliance of each country with such standards.

2. Adopt the FATF compliance indicator and similar indicators

From a technical standpoint, official indicators on financial transparency could be produced and communicated by the intergovernmental institutions that have made specific and practical contributions to the international agenda on financial transparency. These are the BEPS project, the Global Forum on Information Exchange with Tax Purposes, and the FATF.

Given the current international consensus on financial transparency, the simplest and most effective indicator for monitoring the alignment of countries with SDG target 16.4 is arguably counting the number of FATF recommendations that a country has fully complied with using the FATF mutual evaluation system. FATF currently provides data on this indicator for the 99 countries involved in the fourth round of evaluations and has revealed that there are significant discrepancies when it comes to compliance with international financial transparency standards throughout the world.

3. Tap into the G20 comparative advantage to strengthen peer pressure on financial transparency

Although easy to implement from a technical standpoint, the recommendation above consists of ranking and comparing countries on the sensitive issue of the fight against dirty money, and as such, it requires political impetus. This can be provided by the G20.

While the G20 played a leading role in St Petersburg in 2013 when the BEPS project was launched, the G20 has also made many other statements related to this agenda that are simply irrelevant, as they repeatedly endorse international rules adopted at broader and more inclusive forums. The international political capital of the G20 would be better invested in enforcing compliance with these rules. More precisely, the Finance Ministers and Central Governors’ meetings could request that the FATF include a compliance ranking in its inputs to their meetings and communiques.

This initiative would necessarily have to be launched by the G20 Heads of State and Government, but the Finance Ministers and Central Governors could ensure its correct functioning. They are the recipients of an annual FATF report, and they attract sufficient political and social attention to increase pressure on countries. This could, in turn, enforce the FATF recommendations and other financial transparency rules. Eventually, they could also follow up on compliance with other international standards, which are not under the scope of the FATF, such as those on Legal Entity Identifier or Automatic Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Argentinero, Amedeo, Michele Bagella, and Francesco Busato. 2008. “Money

Laundering in a Two-Sector Model: Using Theory for Measurement.” European

Journal of Law and Economics 26 no. 3: 341–59. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1263945.

Basel Institute on Governance. 2019. “Indicators Used in the Basel AML Index.” Basel

AML Index. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://www.baselgovernance.org/basel-amlindex/methodology/indicators#17.

Cobham, Alex. 2012. “Tax Havens and Illicit Flows.” In Draining

Development?: Controlling Flows of Illicit Funds from Developing

Countries edited by Peter Reuter, 337–72. Washington, DC: The World

Bank. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/2242/668150PUB0EPI0067848B09780821388693.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=355 .

Cobham, Alex, and Jánský, Petr. 2020. Estimating Illicit Financial Flows: A Critical

Guide to the Data, Methodologies, and Findings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Colaco, Francis, Alexander Fleming, James Hanson, Chandra Hardy, Keith Jay, John

Johnson, Andrew Steer, Sweder Van Wijnbergen, and K. Tanju Yurukogl. 1985. World

Development Report. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Accessed August 17, 2020.

https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/1985/01/17390599/world-developmentreport-1985.

ECOLEF. 2013. “The Economic and Legal Effectiveness of Anti Money Laundering

and Combating Terrorist Financing Policy (ECOLEF).” JLS/2009/ISEC/AG/087. Utrecht

University; European Commission, Directorate-General (DG) Home Affairs.

FATF. 2012. The FATF Recommendations. Paris: FATF.

Camdessus, Michel. 1998. “Money Laundering: The Importance of International

Countermeasures.” Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. February 10, 1998.

https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/sp021098.

Le Clercq, Juan Antonio, Gerardo Rodríguez, and Israel Cedillo. 2019. “¿Cómo Medir El

Combate a Los Activos Derivados De La Corrupción Y La Delincuencia Organizada?

(How to Measure the Fight Against Assets Derived from Corruption and Organised

Crime).” Mexico: Universidad de Las Américas, Puebla.

Hendriyetty, Nella, and Bhajan S. Grewal. 2017. “Macroeconomics of Money

Laundering: Effects and Measurements.” Journal of Financial Crime 24, no. 1: 65–81.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-01-2016-0004.

Moiseienko, Anton, and Tom Keatinge. 2019. The Scale of Money Laundering in the

UK: Too Big to Measure? London, UK: Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

OECD. 2014 Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: Measuring OECD

Responses. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264203501-en.

Pietschmann, Thomas, and John Walker (Eds.) 2011. Estimating Illicit Financial Flows

Resulting from Drug Trafficking and Other Transnational Organised Crime: Research

Report. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Pérez, Aitor. 2020. “International Financial Transparency.” Elcano Working Paper, 17.

Accessed July 29, 2020. https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano_en/contenido?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_in/zonas_in/wp17-2020-perezinternational-financial-transparency.

Reuter, Peter, and Edwin M. Truman. 2004. Chasing Dirty Money: The Fight Against

Money Laundering. Danvers: Institute for International Economics.

Schneider, Friedrich. 2006. “Shadow Economies and Corruption All Over the World:

What Do We Really Know?” Johannes Kepler University of Linz and IZA Bonn.

Discussion Paper No. 2315. https://ftp.iza.org/dp2315.pdf.

Tax Justice Network (TJN). 2020. Financial Secrecy Index 2020 Methodology.

Last updated March 3, 2020. https://www.financialsecrecyindex.com/PDF/FSIMethodology.pdf.

Appendix

[1] . Global Financial Integrity uses the IFFs approach described previously in the paper.

[2] . For further information on achievements and challenges in measuring IFFs, see also le Clercq, Rodríguez, and Cedillo (2019), Cobham and Jánský (2020), Pérez (2020)

[3] . For similar information on the 99 countries, see Appendix I.

[4] . The scope of the FATF 40 recommendations and the related assessments contained in the FATF peer reviews would allow for setting up of a composite index with at least five dimensions of a country’s commitment to combatting IFFs: institutional strength, the rule of law, coordination and cooperation, criminalization and results, and governance.

[5] . By measuring progress in policy responses against IFFs instead of quantifying them as such, we take a similar approach to that of the Financial Secrecy Index produced by the Tax Justice Network, which has pioneered research and advocacy on IFFs. The FSI compared to the indicator proposed in this brief is broader from a conceptual standpoint and more complex to calculate. Additionally, although it draws on many official sources, it does not entirely rely on them.