In a time of global crisis, international policy coordination is quite natural. Yet, in normal times such coordination becomes a challenge. This is an issue especially when it comes to monetary and macroprudential policy of globally influential countries. This is especially relevant now with the trend of monetary normalisation in many of these countries.

In this brief, we propose four necessary steps to help addressing these challenges:

- Monetary policy should take into account its spillovers on financial stability

- Systemic central banks need to account for the global impact of their policy

- Multilateral consultations may provide a useful platform to assess these impacts

- The analysis that helps designing monetary and macroprudential policy should include global aggregates to capture the global economic and financial context.

Challenge

Global financial stability remains a major concern for policymakers, especially now that some of the systemically important central banks are normalizing their monetary policy(1). More specifically, the challenges are:

• Monetary policy and its transmission mechanism towards inflation and to the real cycle have become less predictable, due to the “extraordinarily accommodative and prolonged monetary easing”. Hence, exiting this phase is a major challenge (2).

• Yet, monetary policy has an impact on investors’ risk appetite and on financial stability, especially when it comes to systemic central banks such as the Fed.

• Global financial stability would benefit from more coordination of monetary policies. Unfortunately, such a solution is rather unlikely (3). Moreover, internalizing spillovers and spillbacks of monetary policies is far from technically straightforward.

• There is evidence of a global financial cycle whereby monetary decisions in major financial centers – and, in particular, in the USA – drive capital flows all over the world influencing the supply of credit and its international distribution (4).

• As the global financial cycle is not aligned with individual countries’ specific macroeconomic conditions, international capital flows can cause financial booms and instability, quite independently of exchange rate regimes (5).

• In a time of global crisis, international policy coordination is quite natural. Yet, in normal time such coordination becomes a challenge. This is an issue especially when it comes to monetary and macroprudential policy of globally influential countries.

In this brief, we propose four necessary steps that, we believe, would help address these challenges:

– Monetary policy should take into account its spillovers on financial stability – Systemic central banks need to account for the global impact of their policy

– Multilateral consultations may provide a useful platform to assess these impacts

– The analysis that helps design monetary and macroprudential policy should include global aggregate to capture the global economic and financial context.

Proposal

At the country level, the interconnection between monetary policy and financial stability cannot be ignored

In a time of crisis, domestic policy coordination is quite natural as all the different authorities in charge of fiscal, monetary and financial stability policies cooperate to minimize the scope of the crisis and to restore the financial stability.

However, in normal times, things are more challenging as the goals of the different economic policies do not automatically converge anymore: monetary policy target prices and economic stability while the financial-stability policy focuses on enhancing the resilience of the financial system so it can fulfill its three main functions (to provide the core financial services of intermediation, risk management, and payments) even when under significant stress.

Coordination between both policies is not easy for several reasons: measuring financial stability is a controversial exercise; financial stability can sometimes require monetary policies that do not favor price stability; it depends heavily on factors that are far from being controlled by monetary authorities; financial stability issues are often heavily politicized and could endanger the independence of monetary policy (6). Yet, many central banks during the last decade worked at strengthening the resilience of the financial system.

We agree that “central banks should care about financial stability to the extent that it affects the health of the real economy”(7). In other words, while financial stability should not be added to the monetary policy mandate, the design of the policy should take into account the spillovers and other linkages between the monetary policy actions and financial stability (8). However, this requires close monitoring of the financial system and access to relevant information, beyond the banking system.

We encourage the G20 to pursue its effort to identify and collect relevant data to better monitor the global financial system. Transparency in the data collecting process as well as their careful analysis is essential for that effort to be effective and for the central banks to assess properly potential vulnerabilities within the financial system that could be relevant when designing monetary policy strategy.

Some degree of international coordination is necessary

In a time of global crisis, international policy coordination is quite natural. Yet, in normal times such coordination becomes a challenge. When it comes to monetary and financial stability policies the lack of global coordination may generate unwelcome policy spillovers (9) More specifically:

- Monetary policies of systematically important central banks have an impact on the global financial cycle

- drive capital flows all over the world affecting the supply of credit and its international distribution. This is especially true for policy made in the US. – As a result, many countries have to implement macroprudential answers to counter the destabilizing effects of the US policy on their economies.

While ideally, one would like to have international coordination of monetary and macroprudential policies, such a goal seems quite difficult to achieve, especially due to the heterogeneity of the different economies across the world. However, as suggested by Former Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen, systemically important central banks, such as the Fed, must account for the spillover effects of their monetary policy on the global economy when designing it (10).

We believe that systemically central banks would benefit from having the opportunity to discuss the impact of their policy on the global economy with their peers. In other words, this would help them “recognizing and internalizing the unwelcome spillovers that policies can have, especially if financial cycles are not synchronized across countries”(11,12).

We suggest that the G20 entrusts the Global Monetary Policy Coordination Meetings (GMPC meetings), proposed in a T20 2018 policy brief, with the task of discussing and assessing the global impact of the different monetary and macroprudential policies, with a special focus on actions taken by systemically important countries (13) The G20 should then rely on an IMF-FSB taskforce to communicate the GMPC meeting conclusion.

Relaunch multilateral consultations will facilitate cooperation.

Prior to the global financial crisis, the IMF was worried about balance of payments imbalances, emphasizing the need for more global cooperation as early as 2006.The result was an innovative effort of policy coordination among the main protagonists of the world economy. “Multilateral consultations” on global imbalances were launched convening a selected group of five countries to discuss their policy plans and commit to take appropriate measures to address vulnerabilities that affect individual members and the global financial system (14,15). Unfortunately, the multilateral consultations have been abandoned due to more urgent matters related to the global financial crisis (16).

The current situation of the world is such that global divisions and tensions seem stronger than cooperative efforts and symptoms of macro-financial fragility tend again to be overlooked. We therefore propose the use of these multilateral consultations, based on the IMF model. The consultations should concentrate on the current topical needs. We think the level of global debt is one of them. The multilateral consultations would complement the agenda of the GMPC meetings as they can involve smaller groups of countries and may allow more targeted programs on issues such as debt adjustment.

Furthermore, one important task of global coordination is to avoid that the less advanced and less financially powerful countries become victims of the financial disorder of the big ones. Multilateral consultations (and GMPC meetings) are the right forums to make sure these nuances are not ignored. Even more important, that they are taken into account in the design of some policies.

The inclusion of global aggregates when assessing a country’s economic performance and financial resilience is necessary.

After the crisis, the G20 was fairly effective in pushing for changes in regulations that made the financial system of many countries more robust and resilient to shocks. In particular, banking systems (especially US banks) have been better capitalized while complex and opaque financial assets have been somewhat better regulated. However, new dangers seem to come, for instance, from booming “leveraged loans”.

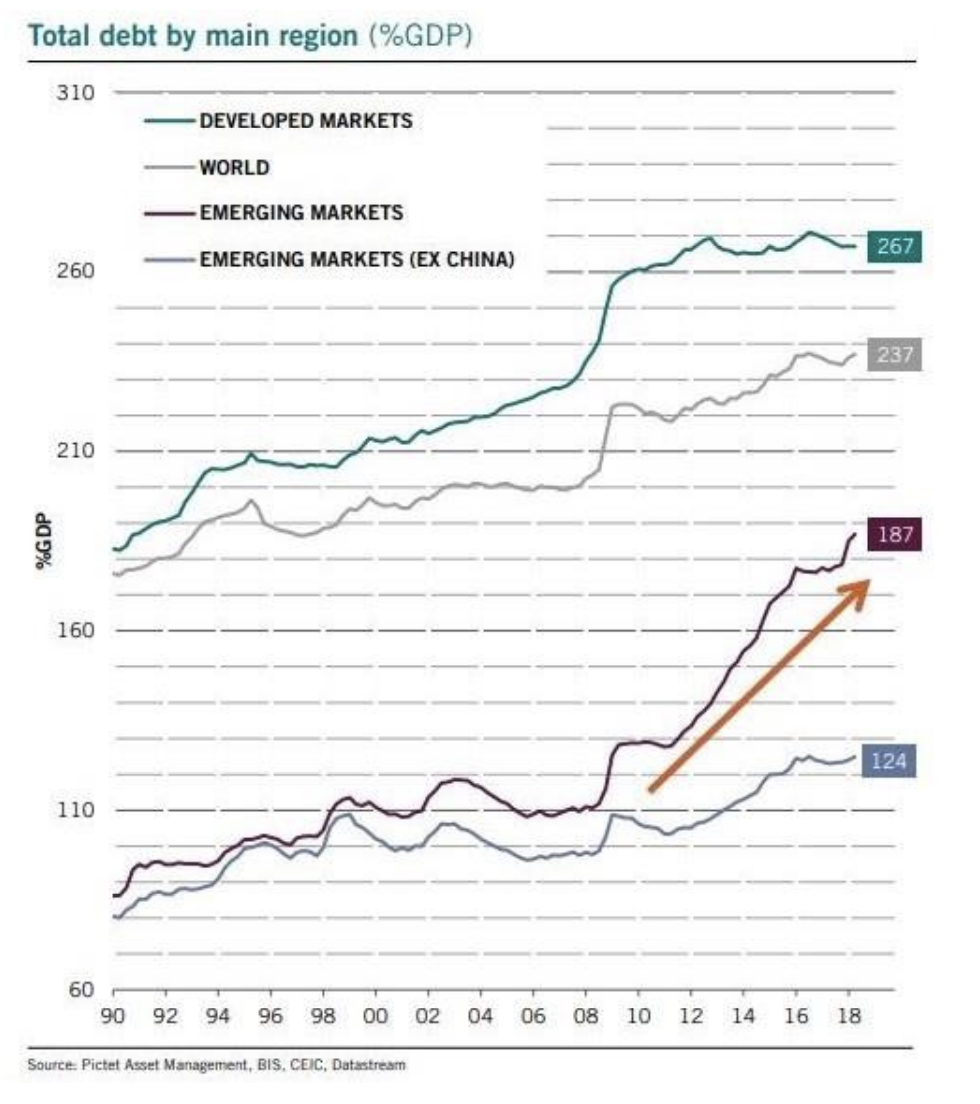

The continuous increase of public and private debts measured in terms of GDP at the world and regional levels signals a potential danger of financial instability. All evidences show that the ratio has gone up after 2008 – which was largely caused by excessive debt accumulation – even more than before (see the Figure below). (17)

While macroprudential policies could help in keeping credit-to-GDP ratio in better control, the contribution of monetary policies to the increase in global indebtedness cannot be ignored. Even more, it seems essential that regulators keep track of the global economic and financial evolution as it influences the economy of their country. Hence, it should also affect their assessment of it.

The use of global indicators such as global debt-to-GDP could facilitate that. This is especially true when the country significantly contributes to the global indicator considered. Defining some acceptable benchmarks or targets may also help the assessment and the design of relevant policies.

We propose that the G20 advocates for the use of specific global indicators when countries assess their need of monetary and macroprudential policy. This would allow them to take into account the global economic and financial context and to anticipate some of the spillovers from the global system to their economy as well as their contribution to any global vulnerabilities.

REFERENCES

• Bank for International Settlements. (2018). Annual Economic Report. BIS report

• Borio C. (2012). The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt?. BIS Working Papers No 395

• Borio C., Disyatat P. (2011). Global imbalances and the financial crisis: Link or no link?, BIS Working Papers no 346.

• Bracke T., M. Bussiere, M. Fidora and R. Straub. (2008). A framework for assessing global imbalances, Occasional Paper Series No 78, European Central Bank.

• Bruni F., J. Siaba Serrate J., and A. Villafranca (2018). Global Monetary Policy Coordination Meetings, T20 Argentina 2018.

• Bruni F., J. Siaba Serrate J., and A. Villafranca (2019). The quest for global monetary policy coordination, Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 13: 1–16.

• Committee on International Economic Policy and Reform. (2012). Banks and Cross-Border Capital Flows: Policy Challenges and Regulatory Responses, Brookings Institution.

• Committee on International Economic Policy and Reform. (2011). “Rethinking Central Banking”, Committee on International Economic Policy and Reform, Brookings Institution. • IMF (2007). The multilateral consultation on global imbalances, IMF Staff paper 07/03.

• IMF (2019). New data on global debt, IMF Blog.

• Lane P.R., G.M. Milesi-Ferretti G.M. (2007). Europe and Global Imbalances, Economic Policy.

• Lopez,C., D. Markwardt and K. Savard (2015), Macroprudential Policy: A Silver Bullet or Refighting the Last War. Milken Institute Report

• Lopez, C., J. Adams-Kane, E. Saeidinezhad and J. Wilhelmus (2018) Macroprudential Policy and Financial Stability, Where do we stand?. Milken Institute Report.

• McKinsey Global Institute (2018), Visualizing global debt, June,

• Mester, L. (2016) Five points about monetary policy and financial stability, Sveriges Riksbank Conference on Rethinking the Central Bank’s Mandate, Stockholm, Sweden

• Plosser, C.I. (2018), Some Thoughts on International Monetary Policy Coordination. Cato Journal.

• Rey H. (2018). Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, NBER Working Paper 21162, May 2015, revised February 2018 https://www.nber.org/papers/w21162.pdf

• Suominen K. (2010). Did global imbalances cause the crisis?, VoxEU.

• Svensson L.E.O. (2018). Monetary policy and macroprudential policy: different and separate?, Canadian Journal of Economics.

• Yellen (2019), Fed must account for spillovers of monetary policy, Central Banking Newsdesk, 20 February.