Despite neutering the official monitoring of protectionism, unmistakable evidence assembled from state sources demonstrates that G20 members routinely violate their “no protectionism” pledge. The scale of trade affected should concern senior officials: by March 2018 over 80% of G20 goods exports competed against trade distortions implemented since November 2008 that were still in force. That percentage falls to 30% if export-related trade distortions are set aside, a total that excludes as yet unimplemented recent high-profile import restrictions.

Concerns that the current G20 approach does not address the full range of policy intervention that distort 21st century commerce should be addressed by Leaders taking two steps: expanding the scope of the G20 protectionist pledge and calling for upgraded monitoring.

Rather than engaging in another fruitless debate about what constitutes protectionism, a principle-based approach should be pursued. G20 Leaders should adopt text that condemns any discriminatory policy intervention, unless a widely-accepted exception is invoked that is justified by evidence, least distortive, implemented only after completing established procedures, and subject to timely review.

G20 Leaders should also adopt text calling on relevant international organisations to redouble their monitoring efforts in line with this principle-based approach and to improve substantially their coverage of the services and intangible economies.

Challenge

To Counter Unfolding Protectionist Dynamics

“We underscore the critical importance of rejecting protectionism and not turning inward in times of financial uncertainty.”

First G20 Leaders Summit Declaration, November 2008

“We will not repeat the historic mistakes of protectionism of previous eras.”

Second G20 Leaders Summit Declaration, London, April 2009

An alien visitor from Mars would be puzzled by current trade policy dialogue among the G20. Our visitor, having read many official monitoring reports on crisis-era protectionism, would be reassured that everything is under control. That is, that there is no threat to an open world trading system that supports the livelihoods around the globe. But when our visitor listens to the news they would hear accusation and counter-accusation about unfair trade practices, excess capacity, trade distorting subsidies, abuse of permitted WTO exceptions, etc.

Thinking hard our visitor might wonder if the G20’s original purpose of their Protectionism Pledge—to eschew the trade policies that restricted manufactured goods trade so much in the 1930s (see the second quotation above)—is out of date and that the commercial realities of the 21st century require tracking a wider range of policy intervention distorting cross-border commerce. The next two sections of this Policy Brief present evidence that bears out our visitor’s supposition. Two recommendations for G20 Leaders follow as well as suggested text for inclusion in their 2018 Leaders Declaration.

Although the focus of this Policy Brief is on protectionism, needless to say that trade and investment reforms by any G20 member, such as those implemented by Argentina in recent years, are to be welcomed and encouraged.

Proposal

The Critics Are Right: The G20 has fallen short on its Protectionism Pledge.

From the start, two design flaws undercut official reports on protectionism prepared for the G20: limiting the policies monitored principally to import and export restrictions used extensively in the 1930s and to contingent protection measures; and a deliberate decision not to update earlier totals for protectionism when new information became available. Moreover, official monitoring of protectionism was compromised by a lack of cooperation in verifying policy intervention by certain G20 member governments[1]. This is in addition to the general problem of governments failing to make timely notifications to the WTO, as its Secretariat has noted, in particular in the area of subsidies.[2] No wonder, then, whether measured as counts of policy interventions or trade covered, the latest official report, like its predecessors, produced tiny headline numbers (see Executive Summary of WTO 2017a).

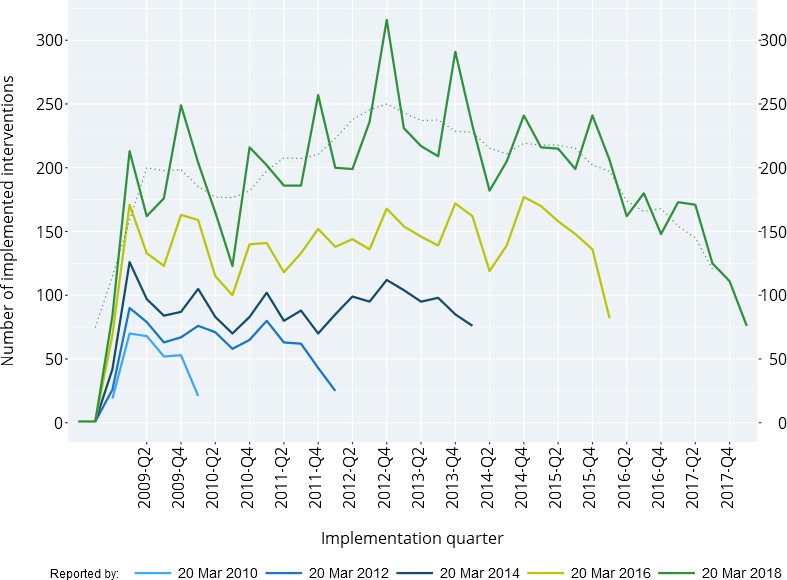

Once the two design defects are remedied a more realistic picture of G20 protectionism emerges, see Figure 1. This figure, based on data collected almost entirely from official sources by the independent Global Trade Alert[3] trade policy monitoring initiative, demonstrates the G20’s sustained resort to new protectionism. This Figure also shows how much initial totals substantially underreported the true amount of protectionism implemented by G20 members.

Currently available information implies that a total of 200-250 new policy interventions that harm foreign commercial interests are implemented each quarter by G20 governments. The extensive resort to protectionism is laid bare by the fact that, since the first Leaders’ Summit, G20 governments have implemented 6,842 distortions to global commerce. Only 34% of them were the import and export restrictions that our grandparents would have been familiar with from the 1930s. Over 3,200 G20 trade distortions involve some type of state aid (however less than 3% of which targeted the financial sector.)

The critics are right to point to all manner of subsidies and non-tariff barriers that have sprung up in recent years. Just because official monitoring did not shed light on them, and just because few such trade distortions have been addressed in WTO dispute settlement, doesn’t mean that they don’t exist and that they don’t matter.

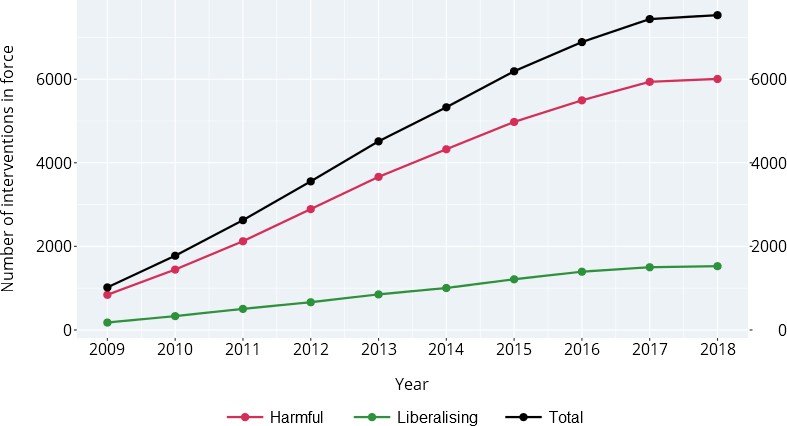

Figure 1: Persistent monitoring of protectionism matters—evidence suggests that each quarter G20 members implement new 200-250 distortions to global commerce.

Source: Global Trade Alert, 20 March 2018. This chart shows total number of new policy interventions by G20 governments that treat domestic commercial interests better than foreign rivals. The reporting dates show how quarterly totals have increased over time as more information about policy intervention has become available. Totals for recent quarters fall off because of reporting lags.

Nor was G20 protectionism a spasm at the beginning of the crisis that was contained successfully. Resort to G20 protectionism has been sustained since the onset of the global financial crisis. Taking account of the phasing-out of temporary protectionist measures and the unwinding of other discriminatory policy intervention, Figure 2 plots the number of protectionist measures implemented by G20 governments that were in force at the end of each year from 2009 to 2017 and on 20 March 2018. By 20 March 2018, in total G20 governments had imposed over 6,000 policy interventions that favoured domestic firms over foreign rivals that were still in force.

Figure 2: Over 6,000 policy interventions introduced by G20 members since the crisis began that harm foreign commercial interests are still in force.

Source: Global Trade Alert, 20 March 2018. This chart shows in red the total number of policy interventions by G20 governments that treated domestic commercial interests better than foreign rivals. The green line shows the total number of policy interventions by G20 governments that improved the relative treatment of foreign firms vis-à-vis domestic firms.

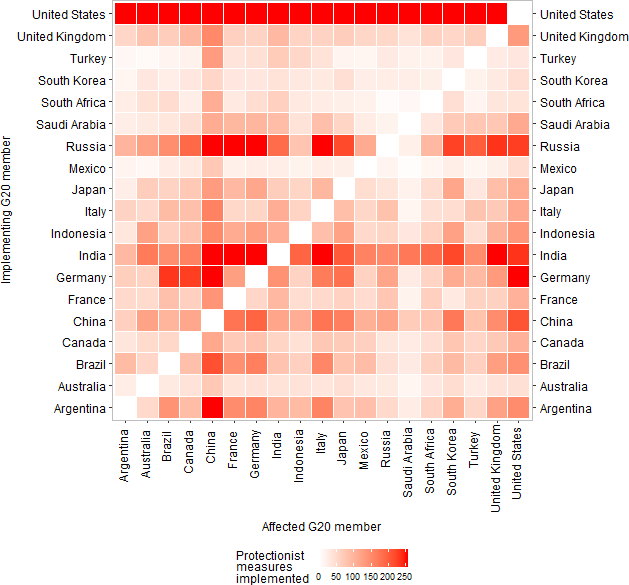

As the largest economies in the world, it is unsurprising that the victims of much G20 protectionism are the G20 itself. Figure 3 reports how many times each G20 member has harmed every other G20 member’s commercial interests since November 2008 and excludes harmful policy interventions that lapsed before 20 March 2018. Figure 3, therefore, provides a current snapshot of how often each G20 member has hit every other G20 trading partner’s commercial interests. Australia, Mexico, and South Korea inflicted harm least often, whereas Saudi Arabia escaped harm the most often.

In light of this evidence, simply put, the 2008 G20 protectionist pledge has not safeguarded the world economy from the harm done by trade distortions. For sure, a Smoot Hawley across-the- board tariff increase by a major trading power has been avoided to date. However, the imports and exports of G20 members are concentrated in relatively few product categories that the trade covered by sustained targeted policy intervention could be substantial (Evenett and Fritz 2017a, chapter 2). Moreover, as some critics point out, avoiding another Smoot Hawley episode is hardly worth celebrating as governments have so many other ways to tilt the commercial playing field against trading partners (as the evidence in the next section will show.)

Figure 3: The number of hits by each G20 member on other G20 members’ commercial interests varies considerably.

Source: Global Trade Alert. 20 March 2018. This tile chart shows the number of times a G20 member harmed every other G20 member’s commercial interests by implementing discriminatory policy interventions that came into force after the G20 pledged to refrain from protectionism in November 2008 and where those policy interventions remain in force on 20 March 2018. That is, protectionism that has lapsed or been removed does not count towards the totals reported in this figure. Looking across the rows in this chart shows how often a given G20 government has taken actions that hit the commercial interests of other G20 members. Looking up and down the columns of this chart shows how often a G20 member’s commercial interests have been harmed by other G20 members. The redder the cell the more incidences of harm were still in force on 20 March 2018.

The scale of G20 commerce affected and the macroeconomic implications of protectionism.

In identifying priorities for tackling protectionism, the starting point should be the observation that modern economies involve both making things and creating intangibles, including services. Each is discussed in turn.

Using fine-grained United Nations trade data, as well as the Multi-Agency Support Team (MAST) classification of non-tariff measures, it is possible to estimate in each year the percentage of G20 goods exports affected by policy interventions that tilt the commercial playing field against foreign rivals and that were documented by the independent Global Trade Alert team. Table 1 reveals that, since the G20 Leaders adopted their no protectionism pledge in November 2008, the percentage of G20 goods exports facing harmful policy acts has risen from 40% in 2009 to 80% in the first quarter of 2018.

Just under 9% of G20 goods exports compete in foreign markets where import tariffs have been raised. Contingent protection—which includes anti-dumping duties that some seek to exclude from G20 work on protectionism apparently on the grounds that they can be a response to other trade distortions—affect less than 2% of G20 goods exports and are, therefore, a sideshow. To date, then, the action has not been in import restrictions.

Nearly 19% of G20 exports compete in foreign markets against a subsidised or bailed out domestic firm. Three-quarters of G20 exports now compete in foreign markets against foreign rivals that are eligible for some form of state export incentive, often an incentive buried in national tax systems.[4] G20 policymakers must recognise that artificially inflating exports and keeping afloat failing firms is where the “action” is (for further evidence see the fourth chapters of Evenett and Fritz (2017a,b)). These measures also harm Least Developed Countries (LDC) too, see the text box on page 7.

G20 officials should reflect on the broader macroeconomic consequences of these findings. Far- reaching subsidies and export incentives cost money and affect the public finances. Worse, as the experience of Brazil during 2015 and 2016[5] demonstrated, once exporters get used to state support they oppose its reduction, with longer term implications for budget deficits. Engaging in zero-sum contests for foreign market share is a recipe for wasting resources and won’t do much to stimulate export-led recoveries. Moreover, propping up zombie firms with subsidies or help from national banking systems has an important opportunity cost—the associated resources could have been used to finance the expansion of growth poles of national economies.[6]

As far as the intangible economy is concerned, evidence is now building up that G20 governments are discriminating against foreign data service providers. Unnecessarily broad rules on local data storage, local data processing, and cross-border data transfer, to name just a few, threaten the business models of cutting-edge firms. By November 2017 the independent European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) had documented 87 such restrictions (Ferracane 2017). Evidence is now mounting up on the adverse impact of such restrictions on GDP. An earlier ECIPE study had identified a patchwork of 22 such restrictions across member states of the European Union and estimated that forestalling the EU-wide application of those measures would avoid annual economic losses of 52 billion Euros (Bauer et al 2016). Given the weak recovery of the EU economy, this is not the time to absorb a further recurring 0.4% loss in GDP. Similar losses were estimated in a study of an ill-advised Russian data localization regulation (Bauer et al 2015).

| G20 Protectionism threatens LDC attainment of the SDGs Countries cannot achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) if they cannot develop their economies. Transformation of their economic structures is essential and trade and migration are fundamental enablers of this process. Unfortunately, the widespread protectionism in the G20 countries is limiting their contributions to growth. Recent evidence assembled by the Global Trade Alert team in March 2018 shows that 79% of LDC goods exports compete in foreign markets against a trade distortion implemented by G20 countries. Whilst 4.3% of these trade distortions are tariff increases and 19% are due to non- automatic licenses, most of the distortion is associated to the different forms of subsidies to exports, primarily thorough the export incentives provided by the national tax systems. Not only LDCs (and other developing countries) find it increasingly difficult to export to the G20 countries, but they also face subsidised competition in third markets. Subsidies to fishing are one of the most high profile acts by certain G20 members that distort resource allocation, exacerbate global income inequality, and harm developing countries.[1] In addition to contributing to the depletion of fish stocks closer to the coasts of many developing countries, many G20 subsidies also contribute to the exhaustion of non-renewable resources and increase the pollution of the environment. In addition to the constraint to the trade and economic transformation of developing countries, protectionism in the G20 induces domestic political pressures that induce governments in developing countries to react. In this way, protectionism spreads to developing countries.[1] In addition of the well-known harm to the livelihood of its citizens, protectionism in developing countries will disconnect them from the international value chains and further limit the attainment of accepted development goals. |

More generally, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has noted “an overall tightening of the global regulatory environment for services trade” (OECD 2018). Such statements are confirmed by examining the data in the Global Trade Alert. G20 members have implemented 534 policy interventions that restrict service trade or harm foreign service providers since November 2008. In contrast, on 37 occasions they have liberalised services trade. The fourteen-to-one ratio in favour of protectionism in service trade far exceeds the three-to-one ratio found in goods trade (as implied by Figure 2 above.) Such evidence is particularly worrying given the service sector accounts for the largest share of gross domestic product in many nations.

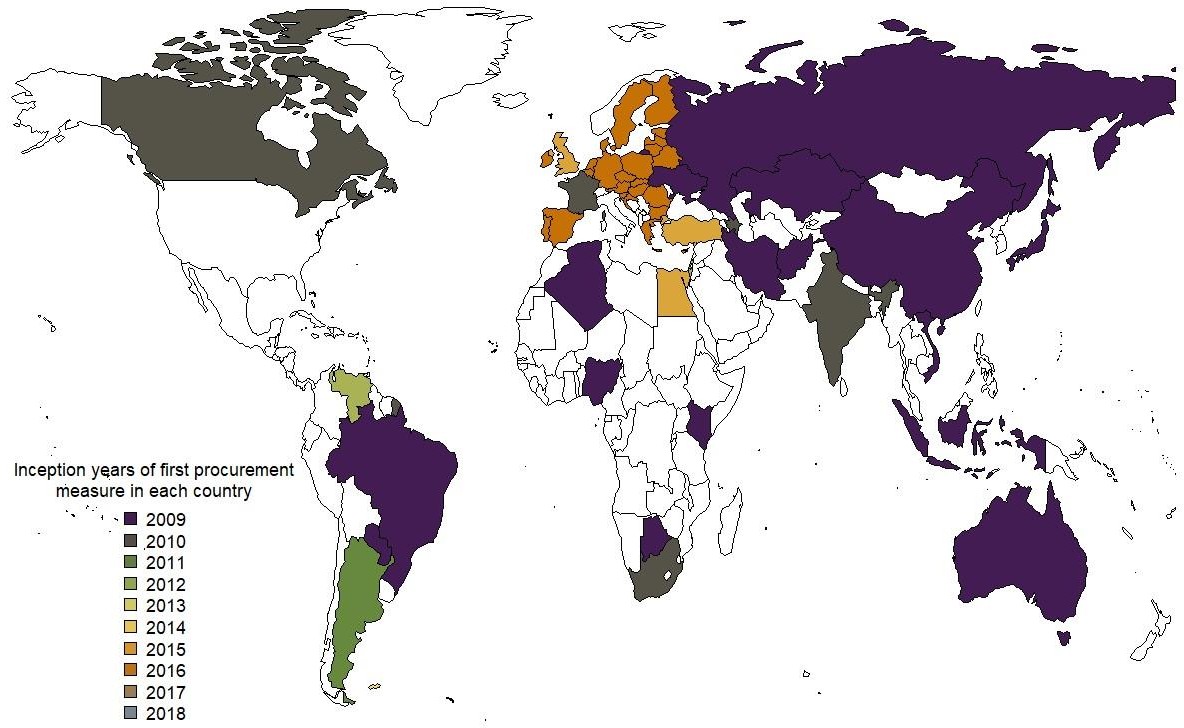

In addition to these actual distortions to cross-border commerce in tangibles and intangibles, an emergent threat relates to G20 countries misusing allowed exceptions to WTO rules. Multilateral trade accords sensibly allow governments to take action in pursuit of certain legitimate societal objectives, but such action is typically conditioned and must follow agreed steps. Moreover, while some exceptions such as those relating to national security exist on the books, until recently governments of major trading nations have wisely eschewed their use. Absent such restraint by the trading powers, copycat behaviour is likely. This is not a hypothetical concern. An example of copycatting behaviour is shown in Figure 4, which reports the worldwide spread of provisions further restricting government purchases to local firms in the wake of discriminatory provisions enacted as part of the US fiscal stimulus package of 2009.

Once the traditional focus on goods trade restrictions is set aside, then more significant protectionist threats to G20 living standards, current and future growth prospects, public finances, and bank solvency become evident. For example, the direct fiscal cost of export incentives as well as the contingent liabilities building up in aggressive trade finance policies— which have long departed from their original goal of helping SMEs to export—have adverse implications for public finances. Propping up zombie firms in sectors with excess capacity threatens bank solvency and limits lending to dynamic firms. Zero-sum industrial policy thinking that fragments markets is increasingly hampering the development of cutting-edge information technologies which benefit most from global scale.

Consequently, the G20 protectionist build up should not only exercise trade ministry officials— finance ministry officials, central bankers, bank regulators and those officials responsible for national economic strategies should be concerned with the sand that the many forms of contemporary protectionism throw into the wheels of economic growth and financial systems. The reality is that sustained attempts to tilt the commercial playing field in favour of domestic firms threatens the G20 economic agenda far more than textbook treatments of trade policy suggest.[7]

Two mutually-reinforcing policy recommendations follow from this factual overview of G20 protectionism and are discussed in the following sections of this Policy Brief. These recommendations take on particular force in 2018 as this year G20 Leaders must decide at their summit whether to renew the G20 Protectionism Pledge, on what terms, and what supporting initiatives—such as the monitoring of protectionism by international organisations—should be undertaken.

Table 1: Eighty percent of G20 exports compete against one or more trade distortions—with subsidies responsible for the largest share.

| UN MAST chapter | Class of discriminatory policy instrument | Percentage of G20 exports facing given trade distortion in overseas markets in given year | |||||||||

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 20-Mar-18 | ||

| All | 40.72% | 57.06% | 59.96% | 65.07% | 68.36% | 74.73% | 78.32% | 79.85% | 80.55% | 80.71% | |

| P7 | Export subsidies | 34.87% | 50.14% | 53.66% | 59.80% | 62.55% | 68.43% | 73.01% | 74.89% | 75.49% | 75.43% |

|

L | Subsidies (excluding P7 and P8) |

5.43% |

8.24% |

9.69% |

11.89% |

13.35% |

14.84% |

15.60% |

16.93% |

18.09% |

18.79% |

| P8 | Export credits | 2.39% | 3.06% | 2.80% | 3.01% | 14.64% | 4.94% | 12.38% | 15.68% | 15.60% | 15.63% |

| Import tariff increases | 0.62% | 1.32% | 1.23% | 1.55% | 3.22% | 6.54% | 6.96% | 7.32% | 8.39% | 8.71% | |

| M | Government procurement | 0.65% | 1.33% | 1.40% | 2.05% | 2.63% | 2.99% | 3.49% | 3.54% | 3.71% | 3.83% |

| E | Non-automatic licensing, quotas | 0.63% | 0.59% | 2.17% | 2.56% | 2.99% | 2.83% | 3.06% | 3.12% | 3.29% | 3.51% |

| Instrument unclear | 0.06% | 0.31% | 0.39% | 0.47% | 0.74% | 1.62% | 3.24% | 3.28% | 3.33% | 3.41% | |

|

I | Trade-related investment measures |

0.23% |

0.77% |

0.82% |

0.91% |

0.93% |

1.33% |

1.86% |

2.34% |

2.37% |

2.34% |

| D | Contingent trade protection | 0.20% | 0.48% | 0.70% | 0.84% | 0.96% | 1.06% | 1.12% | 1.42% | 1.60% | 1.91% |

| F | Price control measures | 0.43% | 0.43% | 0.48% | 0.54% | 0.55% | 0.76% | 1.07% | 1.15% | 1.23% | 1.23% |

| G | Finance measures | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.04% | 0.05% | 0.05% | 0.05% |

Notes:

| 1. Where relevant, policy instruments classified according to the UN MAST categories for non-tariff measures, see https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab20122_en.pdf |

| 2. Only discriminatory policy interventions implemented from 1 November 2008 on were taken into account in these calculations. This is the month that the G20 first stated they would eschew protectionism. Policy interventions by all governments worldwide (not just the G20) are included in the above calculations. |

| 3. When a policy intervention lapses then from that date on it no longer contributes to the export coverage totals reported above. When date of lapse is uncertain the most conservative possible date is used. |

| 4. Data source for underlying policy interventions: Global Trade Alert, where the HS 6 digit classification is used to identify products affected. When there is uncertainty about product coverage the most conservative interpretation is used, including possibly identifying no affected products. |

| 5. Data source for trade flows: UN COMTRADE. |

| 6. As policy interventions can influence the magnitude of trade flows, to avoid concerns about endogeneity these shares are calculated using pre-crisis (2005-2007) shares of observed world trade. |

| 7. The above table refers to the shares of G20 exports in a given year affected by each group of discriminatory policy instrument. A discriminatory policy instrument is one that treats a domestic commercial interest better than a foreign rival. |

Figure 4: Bad ideas spread fast—The spread of Buy National public procurement provisions after the enactment of the US fiscal stimulus package of 2009.

Source: Global Trade Alert. 20 March 2018.

[1] In its September 2017 monitoring report on G20 government intervention, the WTO Secretariat noted “Initial responses to the Director-General’s request for information were received from all G20 delegations. These data, as well as information collected from other sources, were returned for verification. However, in several cases the Secretariat received only partial responses, and often significantly after the indicated deadline” (WTO 2017a, page 8). A lack of cooperation from many G20 members also resulted in the WTO secretariat stopping in 2017 its reporting on “General Economic Support Measures,” typically subsidies

[2] The following observation was made in the WTO Secretariat’s latest overview of trade policy developments:

“The overview of the compliance and timeliness of Members’ notifications to the WTO clearly illustrates that, with a few exceptions, compliance with notification requirements of the various WTO Agreements leaves much to be improved” (WTO 2017b, page 106).

[3] The independent Global Trade Alert team has documented over 15,000 liberalising and protectionist policy interventions that were implemented worldwide since November 2008. In a review of available sources documenting commercial policy choice in 2016, the International Monetary Fund stated the Global Trade Alert “has the most comprehensive coverage of all types of trade-discriminatory and trade liberalizing measures.” The Swedish National Board of Trade also relied on GTA data in their review of protectionism in the 21st century. For this reason, amongst others, the Global Trade Alert data is routinely referred to by corporate executives, by policy makers, in leading media outlets around the globe, and in 1,400 studies and entries in the Google Scholar database. Only 6.8% of the policy interventions documented in the Global Trade Alert database are based on non-official sources.

[4] The extent to which different export incentives are legal under WTO rules is debated. However, for firms competing against rivals benefiting from such incentives, this debate is beside the point as they face pressure to lower prices or lose sales. If any export incentives are indeed WTO legal that merely demonstrates that loopholes exist in a WTO rulebook that has long been thought to ban (for most countries) export subsidies in manufactured goods and, more recently, expanded to include the phase-out of such subsidies in agricultural trade.

[5] September 2015 proposals to cut the tax refunds to exporters associated with the REINTEGRA programme (see https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Brazilian_Government_announces_new_tax_measures/$FILE/201 5G_CM5793_Brazilian%20Government%20announces%20new%20tax%20measures.pdf) were reversed a year later (see https://www.brazilgovnews.gov.br/news/2016/09/brazilian-government-will-raise-tax-rebate-for- exporters). Interestingly, the latter official source noted “According to the organisations that represent export companies, REINTEGRA beneficiaries account for 46% of all jobs in the manufacturing industry.”

[6] Trade officials and experts may not be aware of the extensive analysis done in recent years by the staffs of the Bank of International Settlements, the European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development on the ability of firms in very weak financial situations (so called zombie firms) to survive. To date, the linkages between such firms and trade distortions (the latter possibly as cause or consequence of the former) have not been much discussed in trade policy circles, although those linkages are implied in some discussions about the consequences of sectoral excess capacity.

[7] This is in addition to longstanding empirical evidence linking open trade regimes to economic growth. For a sophisticated treatment of such matters see Wirtschaft Köln / IW Consult (2016).

Policy recommendation 1: Adopt a new, more relevant G20 Protectionism Pledge.

The 1930s-inspired G20 Pledge on protectionism adopted in November 2008 is no longer fit for purpose. No one should be shocked by this statement in the year 2018. After all, it has been more than five years since G20 Leaders at the Los Cabos Summit stated “We are deeply concerned about rising instances of protectionism around the world.” Moreover, in their detailed work on excess capacity in the steel sector, G20 officials acknowledge the adverse role that subsidies and the like can play, going beyond the range of policies considered in the November 2008 Pledge. Furthermore, it is clear that some G20 Leaders believe other governments have systematically cheated both hard and soft trade rules (the 2008 Pledge being an example of the latter.)

The wrong response to dissatisfaction with the 2008 Pledge is to abandon this G20 initiative on protectionism. Little good will come from signalling to the private sector, to financial markets, and to non-G20 governments that there is now a free-for-all in trade policymaking by G20 countries, especially at a time when confidence in the WTO is at a low ebb. Abandoning monitoring of G20 policy choice won’t stop the media and others from pointing out beggar- thy-neighbour policies. Nor will it stop trade frictions—they won’t disappear just because the G20 collectively turns a blind eye to protectionism. Better, then, to upgrade the 2008 Pledge so as to:

- broaden its scope to the include full range of beggar-thy-neighbour policies that distort goods exports and imports, that distort the services and intangible economies, and that hamper foreign direct [1]

- encourage the unwinding of previously implemented trade distortions as well as continuing to discourage the adoption of new protectionist

- identify, examine, and discuss the public finance implications of subsidies, tax incentives, and off-the-balance-sheet liabilities of export credit agencies, in addition to examining the effects on such policy choice on cross-border flows of goods, services, investment, and intellectual

- identify, examine, and discuss the implications of discriminatory policy intervention for medium- and long-term resource misallocation (including the development of excess capacity, the organisation of supply chains, and the misallocation of scarce finance to zombie firms), productivity growth, and other sources economic

An upgraded Pledge would complement other aspects of the G20 trade work programme, in particular attempts to phase-out excess capacity in the steel sector. Interestingly, the G20 Leaders Declarations for 2016[2] and 2017[3] as well as the November 2017 report of the Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity make specific reference in the steel sector to the relevance of a broader range of trade distortions than are the focus of official monitoring of the original G20 protectionist pledge. If it is accepted that a wide range of public policy intervention can tilt the commercial playing field in the steel sector, then it is difficult to see the logic for effectively restricting the G20 protectionist pledge to a narrow range of policy measures in other sectors. This is a plea for coherence in approach—to focus work on protectionism on departures from the principle of non-discrimination rather than on specific pre-selected policy instruments. In the last section of this policy brief we suggest some text for inclusion in the G20 Leaders Declaration for 2018.

The opportunity here is for the new Protectionism Pledge and associated work programme to contribute substantially to the G20’s longstanding objective of promoting global economic recovery, and to strengthen engagement with finance officials and, where appropriate, central bankers and bank regulators on matters of mutual interest. Hence the recommendations above concerning the analysis of the public finance and medium- and long-term resource allocation implications of protectionism, steps which put the Pledge much closer to the overarching growth objectives of the G20.

Policy recommendation 2: Upgrade official monitoring of protectionism.

Official monitoring of G20 public policy choice is a global public good—very few governments can afford their own monitoring initiatives. Official monitoring provides impartial information whose importance is all the greater at a time when some G20 Leaders loudly assert that trading partners have engaged in hidden forms of protectionism and are breaking trade rules. To quote the late United States Senator Patrick Moynihan: “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.” Done well, official monitoring takes disagreements over facts off the table, enabling discussions to focus on the substantive impact of policy measures and steps to encourage the adoption of better practices.

An upgraded G20 Pledge on Protectionism calls for upgraded official monitoring of G20 policy choice. The shackles limiting existing official protectionism should be cast off—the goal of official monitoring should be to provide a complete picture of all relevant government policy choice since the global economic crisis began. G20 Leaders should invite the international organisations responsible to design more ambitious monitoring initiatives—including remedying coverage gaps in the service sector and in the growth poles of the intangible economy—and present a common report to the G20 Leaders Summit in 2019. Such monitoring should include explicit reporting of refusals of G20 governments to cooperate in verifying state acts in a timely manner.

Concluding remarks and suggested text for the G20 Leaders Declaration 2018

When adopting a pledge on protectionism in 2008 G20 Leaders claimed to have learned the lessons of the 1930s. That, to date, there have been no across-the-board tariff increases by major trading nations is a victory of sorts. But that victory is hollow as governments channelled protectionist pressures into other discriminatory policy interventions, including all manner of commerce-distorting subsidies, in doing so harming the commercial interests of the G20 often. So often, in fact, that now 80% of G20 goods exports compete against one or more trade distortions in foreign markets. Competing against multiple distortions is commonplace.

No wonder some ridicule the current system of trade rules. G20 Leaders should rise to the challenge by adopting a new Protectionism Pledge that puts the spotlight on any discriminatory policy intervention that tilts the commercial playing field against foreign rivals in the 21st century global economy, including in the less well-monitored service and intangible economies. A principle-based approach such as this is preferable to another fruitless debate about which policy actions constitute protectionism; focus instead on policy intervention that unduly favours domestic commercial interests over foreign rivals.

Specifically, G20 Leaders should adopt text that condemns any discriminatory policy intervention, unless a widely-accepted exception is invoked that is justified by evidence, least distortive, implemented only after completing established procedures, and subject to timely review.

G20 Leaders should also adopt text calling on relevant international organisations to redouble their monitoring efforts by expanding their scope in line with this principle-based approach and by ramping up their coverage of the services and intangible economies.

With our recommendation to examine the public finance and medium- and long-term resource allocation implications of discriminatory policy intervention, the G20’s work programme on trade policy would move much closer to the G20’s principal economic mission of restoring the global economy to health. Also, this work could ultimately lay the foundation for a revised set of multilateral trade rules, ideally filling in some of the biggest gaps in the WTO rulebook.

[1] Broadening the scope of the Pledge in no way diminishes concerns about the harm to the global economy that would follow from any future widespread resort to traditional trade barriers, such as import tariffs.

[2] That Declaration stated “We also recognize that subsidies and other types of support from government or government-sponsored institutions can cause market distortions and contribute to global excess capacity and therefore require attention.”

[3] That Declaration stated “We urgently call for the removal of market-distorting subsidies and other types of support by governments and related entities.”

References

- Bauer, Matthias, M.F. Ferracane, H. Lee-Makiyama, and E. van der Marel (2016). “Unleashing Internal Data Flows in the EU: An Economic Assessment of Data Localisation Measures in the EU Member States.” ECIPE Working Paper. March 2016.

- Bauer, Matthias, H. Lee-Makiyama, and E. Van der Marel (2015). “Data Localisation in Russia: A Self-imposed Sanction”. ECIPE Working Paper. June 2015.

- Evenett, Simon J., and Johannes Fritz (2017a). Will Awe Trump Rules? The 21st Global Trade Alert Report. CEPR Press. June 2017.

- Evenett, Simon J., and Johannes Fritz (2017b). Europe Fettered: The impact of crisis-era trade distortions on exports from the European Union. CEPR Press. December 2017.

- Ferracane, Martina F (2017). “Restrictions to Cross-Border Data Flows: a Taxonomy”. ECIPE Working Paper. November 2017.

- Wirtschaft Köln / IW Consult (2016). Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln and IW Consult (eds.) Wohlstand in der digitalen Welt Erster IW-Strukturbericht. 2016.

- OECD (2018). OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy trends up to 2018. January 2018.

- WTO (2017a). Report on G20 Trade Measures. 9 November 2017.

- WTO (2017b). Overview of Developments in the International Trade Environment. Annual Report by the Director-General. 16 November 2017. WTO document number WT/TPR/OV/20.