Tight fiscal space because of the response to the outbreak of COVID-19 is forcing governments around the world to pursue higher participation by the private sector in developing and operating ports. The outbreak of COVID-19 has severely disrupted global supply chains placing more focus on the vital role ports play in global trade. Participation of the private sector in developing and operating ports has been successful especially in gateway ports across the Group of 20 (G20) members, with Indonesia being the exception. This paper argues that institutional arrangements, the dominant role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the sector and above all a convoluted port tariff policy stifle port investment. Comparative analysis of port tariff policies across G20 members shows the need for tariffs to recover costs and price formation to take place through competition. Indonesia’s port tariff policy is implicitly attempting to sustain a nationwide cross-subsidy from high revenue-generating gateways to a complex system of domestic trade, non-commercial ports and subsidised shipping. With domestic trade flows outgrowing international flows, this cross subsidy is highly unsustainable. Without port tariff reform it is practically impossible to develop commercially feasible port projects, which are essential in public private partnerships (PPPs).

Challenge

The G20 is held together by close cooperation in the area of trade. Sea transport is the main modality. The outbreak of COVID-19 and the responses by governments across the globe have shown how vulnerable supply chains can be, these disruptions are ongoing[1]. Sea freight rates have escalated rapidly creating an additional tax on trade. Especially in times of turbulence it is critical the port system continues to operate, invest and innovate. Infrastructure has a long economic life and needs to deal not only with the obstacles today but all over the next century that includes pandemics, climate change, automation and digitalisation. After the COVID-19 outbreak the fiscal space of governments is tight, which places more responsibility with the private sector to develop port systems. It is critical the environment is created and sustained to foster participation by the private sector. Most G20 countries have been successful in this area but the analysis of Indonesia has shown that vital reforms are urgently needed. Good ports foster diverse shipping networks that integrate trade, also between G20 members in the South-South sphere. With the current tensions it is important to remember that trade is an effective mitigation tool to avoid conflicts.

Proposal

PPP arrangements rely on (i) user payments, (ii) a single government user paying or (iii) a mix of these where the government payment is a subsidy. Most G20 countries have well established user pay models for the delivery of services and substantial investment in ports, especially mechanical handling equipment within terminals.

This paper sets out evidence that port tariff policy in Indonesia results in different investment returns between international and domestic port investments. More direct evidence for this situation is hidden by the corporate structures of sector SOEs that blend returns from international and domestic ports, hindering transparency. The difference in investment returns is crippling domestic port investment when domestic throughput is outgrowing international throughput (Annex 1). The failure in domestic port investment undermines key government policies on equal opportunity across the archipelago and highlights the urgency of reform.

In Indonesia the dominance of SOEs as port operators and combined with tariff regulation by the Ministry of Transport (MoT) delivers a commercial situation in which the private sector finds it difficult to identify, secure and invest in ports through PPPs or other arrangements. To address this failure, this briefing proposes the adoption of a new policy for port tariff regulation and a new approach to the management of the involvement of Indonesian SOEs in the port sector.

To match best practice in the G20 nations, port tariff regulation reform in Indonesia should focus on two simple principles (i) an obligation for the user to pay the full cost of the services they use and (ii) ensuring competition between providers of port services to limit excessive port charges.

These principles would be implemented through a policy whereby the MoT would revoke all previous tariff regulations related to port services and concessions. In their place, the MoT would institute a transparent complaints process to enable users to make representations to the MoT if they believe tariffs charged are above the full cost of delivering adequate port capability and productivity. If, after review of such complaints, the MoT identifies such claims to be legitimate, it would have the power to require modification of the tariff and take associated remedial measures.

The form and nature of remedial measures would be defined and enabled by the terms of operating licenses (BUP). Potential remedial measures include the conversion of revenue more than 25 percent in excess of the deemed valid user-pays charge into de-facto non-tax state revenue (similar to the existing concession fees).

The policy on management of the involvement of SOEs in the port sector would again match best practices in the G20:

- A ban on SOEs that do not operate ports and terminals as part of their core business from owning shares in port or terminal operations or new developments. Such a policy is in line with the management of SOEs in most G20 countries.

- A ban on the issue of port construction licenses to any SOE already involved in the port and terminal sector for building a new terminal or for a major extension to an existing terminal. This ban to be waived if the SOE can show a clear, detailed and failed process to realise investment from the private sector for the subject terminal or extension. The process of seeking such investment should have been undertaken in a fair and reasonable manner and concluded within the previous six months. Such a policy is in line with best practice across most G20 countries to prioritise private sector infrastructure investment whenever practical and it releases government/SOE funds for more urgent priorities.

The policies set out above are envisaged as the first phase in a longer-term policy initiative designed to achieve full implementation of the 2008 Shipping Law. An inventory of G20 countries shows that successful port operation and development is delivered through the port landlord model that underpins the existing law. Progress towards the implementation of the model has been prevented by the continuing strong presence of SOEs and the associated tight regulation of tariffs. Further phases of policy will need to address the complex geography of Indonesia (a wide variety of different ports, port costs and technical concerns within those ports) and the sensitive subject of land ownership.

Status report on port governance and development in Indonesia

Indonesia is the world’s largest archipelago with 17,000 islands of which 6,000 are estimated to be inhabited. Indonesia also has the fourth-largest population in the world and these two factors combined result in a large and diverse port sector.

The port sector is governed through the 2008 Shipping Law. The aim of this law is to introduce more private sector participation in the development of the maritime sector including ports. The most common port management model found in G20 countries, the landlord model, informs the spirit of the law. The primary focus of the landlord (port authorities) is the creation/maintenance of basic infrastructure and the regulation of private service providers operating basic infrastructure.

Prior to the 2008 Shipping Law, state-owned port companies (Pelindo I to IV) managed the commercial ports of Indonesia. Depending on which company is considered, these companies acted to some degree as a landlord and to some degree as a port operator. The Pelindo companies under the new law were not changed or reformed in any way though, by implication, they were directed to be terminal operators.

To implement the landlord model a new landlord port authority was imposed on the existing governance structure for Indonesian ports. The port authorities were created from existing administrative coordination bodies that existed under the auspices of the MoT. The need to do this was rooted in the law, which determined that port authorities can only be staffed by civil servants. This prevented existing port management and operations, being reformed by Pelindo into port authorities and terminal operators as has been done in many G20 countries (and other countries) over the last 50 years.

The 2008 Shipping Law did not allocate any state assets to support the creation of the port authorities. It did not enable or require the transfer of land that had previously been granted to the SOE port operators (Pelindo) to the port authorities. It also did not require or enable existing basic infrastructure to be transferred to the port authorities. Indeed, the treatment of existing port land, port infrastructure or port operations was not mentioned within the law. This led to the creation of port authorities with no assets to regulate and no means to develop existing large-scale public ports.

Following the 2008 Shipping Law, terminals within commercial ports were to be licensed to operate under concessions or other forms of agreement issued by the port authorities. However, the law made no stipulation on the transfer of land and Pelindo was not willing transfer its assets to the port authorities without appropriate compensation to the satisfaction of the state auditor. In some ports the situation of the Pelindo was further complicated by existing agreements they had with international and domestic terminal operators in the form of concessions (that would need to become sub-concessions), stevedore services agreements and other forms of cooperation agreements (including land leases).

In reality, the new port authorities lacked the funds to so compensate Pelindo. To avoid a long and complex asset transfer process and with no prospect of funding compensation when complete, Pelindo assets were therefore placed under master concession agreements with a 2.5 percent gross revenue fee paid to the port authorities over a term of 30 years.

Hence, although the Shipping Law implicitly directs Pelindo to become an operator, in almost all projects its role resembles more that of a facility developer and provider (landlord), even where is landlord to its own subsidiaries. For example, in Indonesia’s largest port of Tanjung Priok (Jakarta), the three main international container terminals are operated by private international terminal operators[2] under operational agreements that resemble concession agreements found in other G20 countries. In Tanjung Perak (Surabaya) the two major container terminals are now operated by subsidiaries of Pelindo under similar concession agreements found in other G20 countries.

After the enactment of the Shipping Law where Pelindo initiated new build projects, new concessions were created. Some concessions were also issued to private companies. Annex 2 provides and inventory of concession fees and terms for the concessions issued by the port authorities.

The inventory reveals that the average concession fee for a new development by an SOE was 2.6 percent with an average term of 66 years. For private sector concessions, the average concession fee was 4.3 percent with a term of 48 years. Given that the private sector concessions are generally for greenfield developments and SOE concessions for brownfield ones, the disparity in concession fee and length of term is counter-intuitive because the private sector is making investments that are inherently more risky yet are being expected to undertake that investment whilst paying a higher percentage of gross revenue to the government and achieving their investment return in a shorter period of time. For greenfield ports all practical experience is that they find it challenging to integrate into the existing logistics provision of the region or market they are built to serve and require long concession terms.

Since 2008 only one major new port has been developed by the MoT, Patimban (to the east of Tanjung Priok). This port has been developed with the support of funding from the government of Japan (JICA) and was designed as the 100-year replacement for Jakarta’s main port of Tanjung Priok. It is also intended to introduce more competition into the port sector. This has indeed been the case but in practice this means that investors in Tanjung Priok and Patimban see themselves in competition and facing increased demand-side risk.

Another more modest port investment by MoT has been made in Belawan where a reclamation that could be completed as an international container terminal has been carried out with the support of the Islamic Development Bank.

Analysis of the published accounts of the Pelindo companies show they have found it difficult to generate a successful business case for investment in their ports. They have identified markets in Tanjung Priok, Tanjung Perak, Makassar and Belawan but, with the exception of a development in Tanjung Priok, they have failed to develop a successful commercial terminal. This is best shown by the increased level of debt taken on by the companies at unsustainable levels. Only Pelindo 2 has implemented a major development and maintained its debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) at a sustainable level. The primary reasons for these failures are:

- The regulated tariff for international and domestic container handling (and ships) and in particular the differential between international (at a commercial level) and domestic (well below a commercial level)

- Political pressure to implement national strategic projects (for example Kuala Tanjung)

- Competition for funding from other MoT developments

Overall, the problems within the Indonesia ports sector may be summarised as:

- Port authorities are acting as landlord without land and only very limited access to investment funds

- The absence of a clear project pipeline or a lack of willingness to enforce appropriate governance on investments made by MoT and SOEs leading to direct competition between investments made by different actors reporting to the government.

- A blend of international and domestic cargoes that deliver very different revenues but require the same physical investment per unit of cargo.

This paper focuses on the third issue of tariff regulation. The other two issues are essentially governance/political issues.

Tariff regulation in Indonesia and good practice in the G20

Annex 2 provides a conceptual review of port tariff regulation for container terminals across G20 countries. From this review, it is clear that the dominant practices are for container terminal charges to be determined and controlled by competition between terminals subject to oversight governed by competition law. Some 80 percent of G20 countries adopt this stance with some variation in how competition is entertained within port-governance structures. In a further 15 percent of G20 countries, there is clear direct tariff regulation, but basic infrastructure is well funded by government and tariffs set to encourage private sector involvement in operations. Only in Indonesia are port tariffs regulated without reference to the commercial market for maritime services.

In Indonesia, the 2008 Shipping Law establishes the primacy of the MoT, as the representative of government. Table 1 schedules the major ports of Indonesia, which together handle about 80 percent of national port throughput. This table provides strong support for the view of the MoT that the Pelindo companies are monopoly operators within their respective regions. In the absence of a strong competition authority, the MoT therefore believes that tariff regulation is required.

Table 1: Summary of port governance in Indonesia

| Port | SOE (Pelindo) percent | Int./Dom. Split | |

| Landowner | Container capacity | ||

| Tanjung Priok | 100 percent | 5-10 percent | 66/33 |

| Tanjung Perak | 100 percent | 100 percent | 50/50 |

| Belawan | 95 percent | 100 percent | 50/50 |

| Makassar | 100 percent | 100 percent | 0/100 |

| Tanjung Emas | 100 percent | 100 percent | 98/2 |

| Bitung | 100 percent | 100 percent | 0/100 |

As a historical legacy and to regulate monopoly, the MoT therefore continues to set all port tariffs. This regime has numerous elements, including many that should be considered as relics of previous shipping and port laws going back to colonial times. The regulatory regime can be summarised as having five primary elements:

- A rigorous structure for the tariff, defining in effect the services that can be provided

- The historic tariff rates (and by implication the historic services that provided revenue)

- A cost-plus approach to establish the highest rate an operator is allowed to charge

- The regulated tariff acting as a ceiling. Operators may discount from the ceiling to provide incentives to their users.

- Amendments, including increases to rates, require consultation[3] with a broad range of stakeholders. Many of those consulted do not have direct financial interests in the capability, capacity and productivity of the port or terminal. Many of them also have clear conflicts of interest in any rate increase.

A further complication to the situation in Indonesia is that the MoT has chosen to apply the same tariff rates to similar classes of port across Indonesia. The similarities leading to the definition of port class relate to administrative functions and measures rather than factors that impact the actual cost of providing the service for which the tariff rate is charged.

A causal impact analysis of tariff regulation in Indonesia

The primary elements of regulation applied by the MoT conflict with the regulatory approach of all other G20 countries because the competitive pressures are ignored and the investment requirements of the ports are ignored. Rates are adjusted from historic levels according to the profit that is deemed allowable upon written-down and inflation-devalued assets. These rates then cannot be changed without approval from stakeholders. The private sector is provided with no incentive to deliver port infrastructure with the capacity or capability to deliver the services and productivity sought by users. For want of private-sector investors, reliance must then be placed on either the government or an SOE to identify and fund port investments, perpetuating the cycle without regard to the 2008 Shipping Law.

The structure of the tariff also restricts innovation in the provision of port services in Indonesia. Hearsay evidence from shipping companies operating and interested in operating freight roll-on/roll-off (RO-RO) services in Indonesia indicates the severity of this problem. Freight RO-RO services require very limited facilities because the freight drives on and off the ship and is stored within the port for only very short periods (measured in hours). However, the legacy tariff structure does not have any relevant item for this. The SOE therefore indicates it will charge RO-RO cargo at the same rate as a lift-on/lift-off containers or general cargo, thereby removing the key benefit of RO-RO to shippers in low port costs, while at the same time discouraging a more efficient use of port facilities. Innovation is thereby constrained, and logistics costs are maintained at an artificially high level.

Current port tariff policies have a number of negative impacts. First, there is strong evidence that inflation has steadily reduced or eliminated the element of the tariff that allows for the renewal or replacement of aging port assets. Second, larger ships and better productivity can only be realised by investment in new port assets that are more capital intensive: recovery of the cost of that investment requires more of the tariff to be dedicated to paying for the capital cost of the asset. Thirdly, it would appear that historic devaluations of the rupiah against the United States dollar has led to a very significant differential between domestic and international port tariffs. Anecdotal and documentary evidence suggests that, prior to the Asian financial crisis, rupiah-denominated domestic tariffs were equal to dollar-denominated international tariffs. The financial crisis saw a major devaluation of the rupiah vis-a-via the dollar. Domestic economic and political forces since then have meant that the differential for the provision of the same service has never been eliminated by adjusting the domestic rupiah tariff. Without a decisive policy intervention, Indonesia has a differential between these tariffs that is discouraging investment, in particular in domestic trade-oriented port assets.

Cost-plus tariff regulation is a complex exercise. India is the only recent example in the G20 where port tariff regulation has been based on controlling profit or investment return. India has in the last year completed a legislative reform program to cease such regulation. Any regulatory process relying on limiting profit or investment return is complex and subject to substantial error. Throughput volume, capital costs, operating costs, financing costs and risk all need to be addressed. Many other factors including economic growth, differential employment, energy and other cost inflation, exchange rate variations etc. also need to be considered. Current MoT regulations in Indonesia do not address the full spectrum of costs and risk inherent in any port development.

The use of cap tariffs and allowing operators to apply discounts is standard practice within G20 countries where it is relevant. This approach is used in other countries outside the G20. Indonesia does adopt a cap and discount approach but the cap does not reflect the cost of providing the service, especially for port services provided to domestic users.

Perhaps the most problematic primary element of the MoT’s tariff regulation is the need to consult with stakeholders prior to amending any tariff. There are two main concerns:

- The breadth of stakeholders to be covered includes many who are not relevant but may be able to generate political benefits from controlling tariff rates

- Short-term and long-term interests conflict. Many stakeholders have short-term needs that require cost control and resist any increase in port tariffs. These stakeholders will not (may not) ever benefit from investments made by an operator funded by a tariff increase. They have no real incentive to agree to any increase but rather an incentive to delay any change.

Consequences of tariff policy on revenue generation and investment decision making

The causal impact review above provides clear evidence suggesting a change in how port tariffs are regulated in Indonesia, could be beneficial. The comparison between port tariff regulation in G20 countries and that in Indonesia also provides strong themes that could be used within any new policy.

However, further consideration of the need for a change in policy is required. The focus of this further consideration is the impact of port tariff regulation on revenue generation, investment decision and to an extent the regional competitive position of Indonesian ports. Strong empirical evidence related to this consideration is provided by a detailed study by IFC (2019). The IFC study shows how Indonesia’s port tariffs compare and contrast with its regional peers. For the purposes of illustration this paper extracts three examples from the IFC study and provides further context to the examples related to port-governance structures. The three examples are:

- Aggregate ship call charges from port authorities to ships

- Charges made to cruise ships by port authorities

- Ship pilotage fees

Aggregate ship call charges

The IFC report identifies those ports dues and associated charges that are levied for the purpose of developing and maintaining marine access to a port and ensuring safe access to the port. The report notes there are a number of charges that should be aggregated to assess the total cost to a ship of a “port call”, a visit to a specific port.

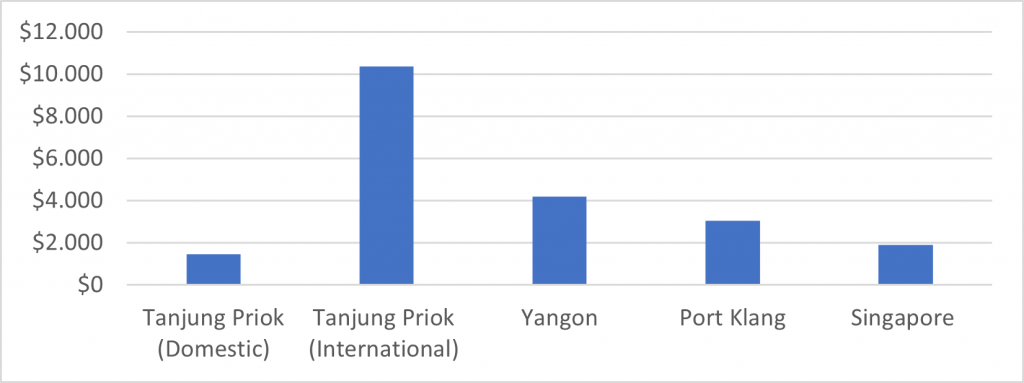

Figure 1 compares for a range of regional ports the aggregate of the port dues, pilotage, tugs and mooring for a 1,200 twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) ship making a port call in which parts of two different days are chargeable. This represents a reasonably standard port call at an Indonesian port. There are two conclusions that can be easily drawn from Figure 1.

First, for international ships, Tanjung Priok is more expensive than other regional ports. Conversely, before other factors are considered, Indonesia’s domestic charges are comparable or more competitive than those made in other regional ports.

Figure 1 Aggregate ship charges for 1,200 TEU ship making two-day ship call

Source: IFC (2019)

Second, a domestic ship pays an order of magnitude less than an international ship for the same service in Tanjung Priok. In no other regional port is there such a vast difference in these charges. This statement also holds for all G20 countries.

Table 2 is extracted from the MoT port tariff regulation; it suggests that an important driver for the difference in aggregate costs for domestic and international ships is the difference in port dues they are charged.

Table 2 Port dues applied in commercial ports in Indonesia

| International (Rp per GT for 30 days) | Domestic (Rp per GT for 30 days) | Traditional (rakyat) (Rp per GT 30 days) | |

| Main Port | 1,518 | 90 | 50 |

| Class 1 | 1,452 | 87 | 47 |

| Class 2 | 1,386 | 84 | 44 |

| Class 3 | 1,320 | 81 | 41 |

| Class 4 | 1,254 | 79 | 39 |

| Class 5 | 1,188 | 76 | 36 |

Source: Government Decree 15 of 2016

Table 2 also provides further insight into tariff regulation in Indonesia. The level of port dues depends on the “class” of port. The class of a port in Indonesia is determined in the National Port Master Plan. Tanjung Priok is a main port and serves Jakarta the capital. It is located on an open coastline with a protecting breakwater that was built in stages since 1890 (the relevance of these statements will become clear).

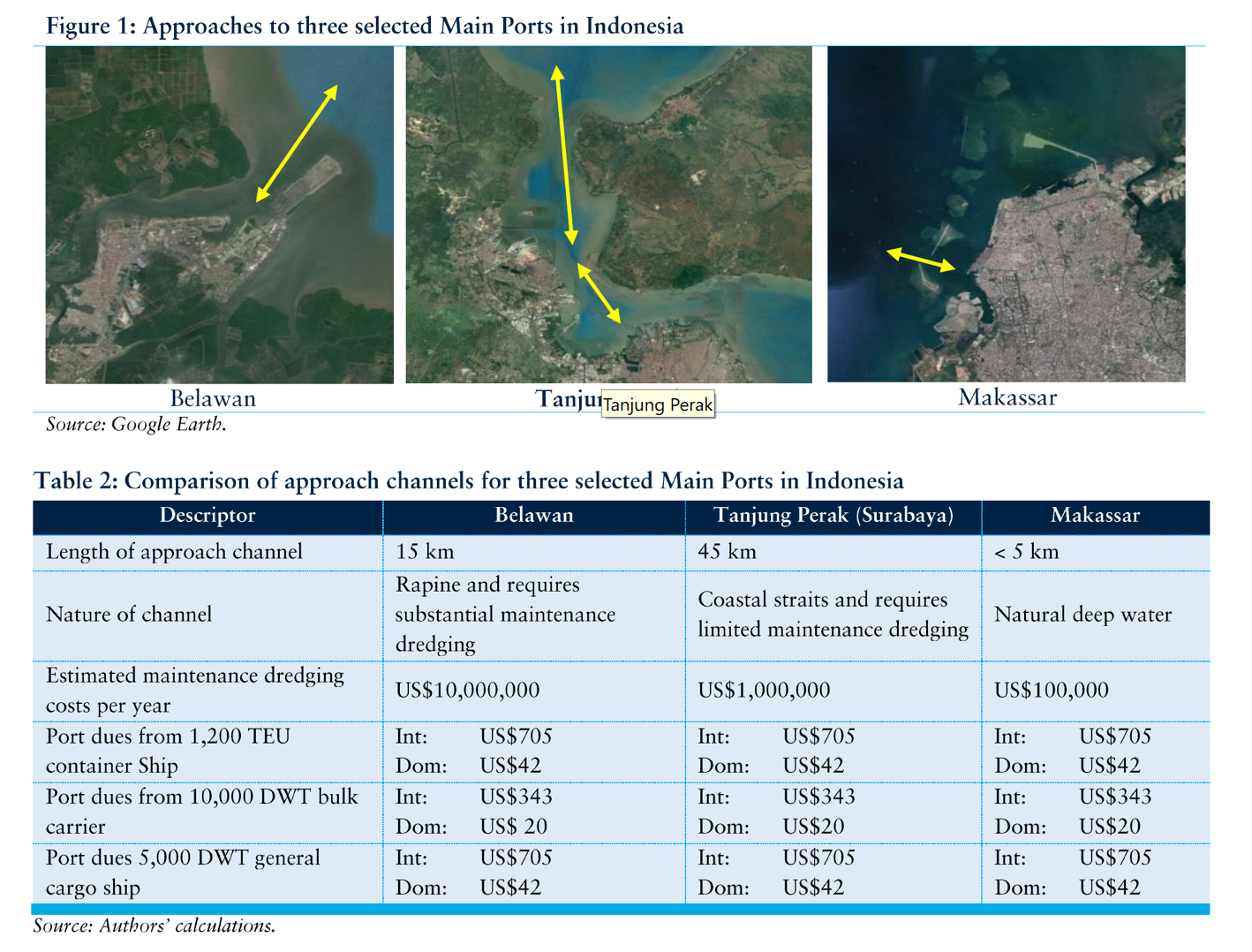

The criteria used to determine the class of a port are of less importance than noting, as the IFC study does, the class of port is not determined by the cost of providing the approach channel and safe marine access. Figure 2 is the repeat of Figure 1 and Table 2 from the IFC study. To complement Figure 2, Figure 3 has been created to provide insight into the regional comparators to Tanjung Priok.

The following observations can be made:

- The cost of creating and maintaining the approach channel to Yangon will be far greater than any other port in the region

- Tanjung Priok should be the cheapest approach channel to maintain but the cost of the breakwater needs to be considered

- Singapore has two reasons why it should be the cheapest port, (i) it has the easiest approach channel to maintain and (ii) as one of the busiest ports in the world it can share the cost out among far more ship calls.

Inherent in these observations is that the cost of developing and maintain the approach channel should be reflected in the aggregate cost of ship calls. In regional competitors, from Figure 1 and 3 this appears to be the case. For Tanjung Priok this cannot be the case.

Figure 2: Approaches to selected ports in Indonesia (from IFC report)

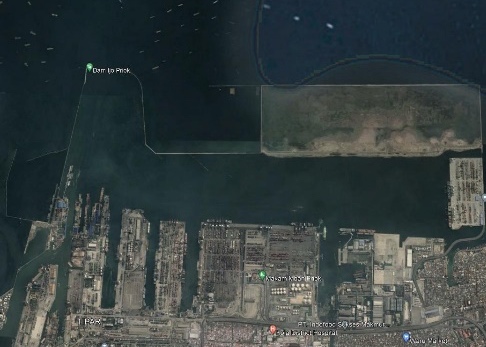

Figure 3: Approaches to regional comparison ports used in Figure 1

|  |  |  |

| Yangon | Port Klang | Singapore | Tanjung Priok |

| Descriptor | Yangon | Port Klang | Singapore | Tanjung Priok |

| Length of Approach Channel | 40 km | < 10km | 5-8 km | < 5km |

| Nature of Channel | Part of large delta for major river (Irrawaddy) | Close to estuaries for small rivers, protected by major offshore islands | Open coastline protected by offshore islands | Open coastline protected by “old” breakwater |

Table 3 investigates the issue of how aggregate port charges are set in G20 countries and whether port governance may be an important factor in the competitive failure of Tanjung Priok as illustrated by Figure 1. From Table 3 the obvious conclusion is that there is no connection between the level of port dues and expenditure by port authorities. In Indonesia, port dues are a non-tax state revenue and are subsumed into general government funds to support overall government spending. In all other G20 countries (and regional competitors) port dues directly support port development and maintenance. In every G20 country excepting Indonesia and in regional competitors the port dues paid are closely related to the cost of developing and maintaining the port they were paid to use.

Table 3: Port governance related to the setting and collection of port dues

| Governance issue for port dues | Indonesia | All other G20 countries |

| Set by | MoT/port authority | port authority |

| Paid by | Ships | Ships |

| Collected by | MoT/port authority | Port authority |

| Allocation and use | Ministry of Finance | Port authority |

| Used for benefit of | Government expenditure | Ships |

Charges made to cruise ships by port authorities in Indonesia

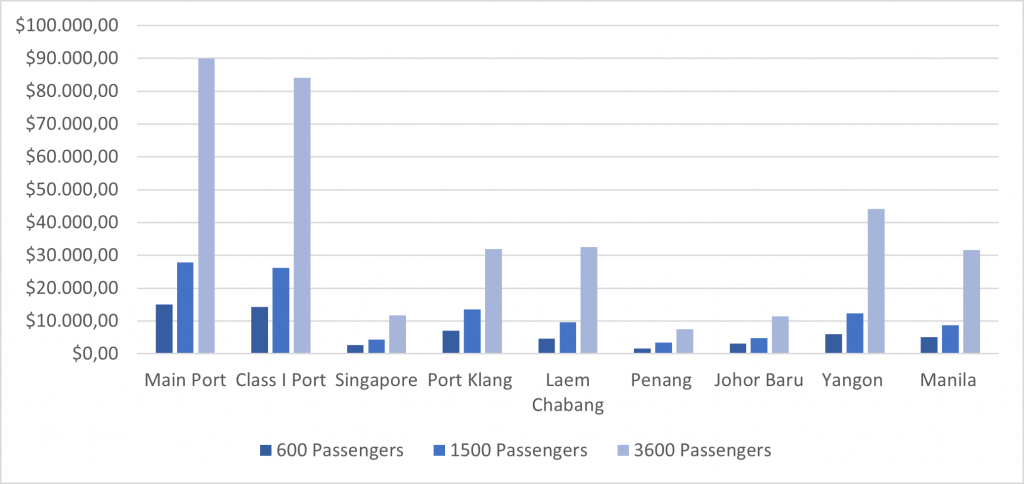

Cruise ships are not a major aspect of commercial traffic for ports across Indonesia. They are claimed to have substantial economic impact and for that reason they attract greater interest than, from a port infrastructure perspective, they deserve. Figure 4 shows the charges made by Indonesian port authorities on cruise ships in a regional context.

The MoT tariff uses gross tonnage (GT) as the key unit of measurement for port dues. This is, in itself, is not unusual. There are arguments that suggest length overall (LOA), deadweight tonnage (DWT) or draft may be more relevant measures that can be used to set port dues. But, Indonesia is not unusual and in line with many G20 countries in using GT.

Where Indonesia departs from general practice in G20 countries is that the tariff does not discriminate between ship type when it uses GT as the key unit of measurement. Cruise ships, freight RO-RO ships and roll-on/roll-off passenger (RoPax) ships all have high GTs. They also have low DWTs (which measures freight-carrying capacity) and low draft (which is important in the design of approach channels). Table 5 illustrates, for ships of similar LOA, these statements. When you add the fact that LOA and beam are when combined with ships’ drafts the keys to designing approach channels, it becomes obvious that cruise ships, freight RORO and RoPAX are very substantially discriminated against by the MoT tariff despite placing less pressure of demand on the infrastructure that port dues are intended to fund.

Figure 4: Cruise ship charges from port authorities

Source: IFC (2019)

Table 5: Illustrative principal dimensions of ships by type

| Container ship | Bulk carrier | Tanker | Cruise ship | RoPAX | |

| LOA | 190.0m | 189.0m | 183.0m | 193.0m | 191.0m |

| Beam | 31.0m | 32.2 | 27.4m | 27.0m | 36.0m |

| DWT | 27,500 | 51,000 | 36,000 | 3,800 | 4,300 |

| GT/GRT | 26,000 | 28,800 | 24,000 | 38,600 | 46,400 |

| Summer Draft | 10.5m | 12.0m | 11.0m | 6.0m | 6.8m |

A conclusion to be drawn from Figure 4 and Table 5 is that port dues in Indonesia are a deterrent to cruise ship calls when compared with other regional ports. This competitive disadvantage is a direct result of the structure of MoT tariffs. A tariff in line with the practices used in other G20 countries would remove this disadvantage. A further conclusion can be reached from Table 5, RORO shipping is discriminated against, this despite it being the most important potential provider of inter-island shipping in Indonesia and despite RORO providing the majority of short sea links through and between G20 countries.

Pilotage fees

Marine piloting is one of the oldest professions in the world. It is a specialist activity that requires high levels of training, certification and attention to safety. Human resources and therefore employment costs are critical to the cost of delivering a pilotage service. This is true in all G20 countries.

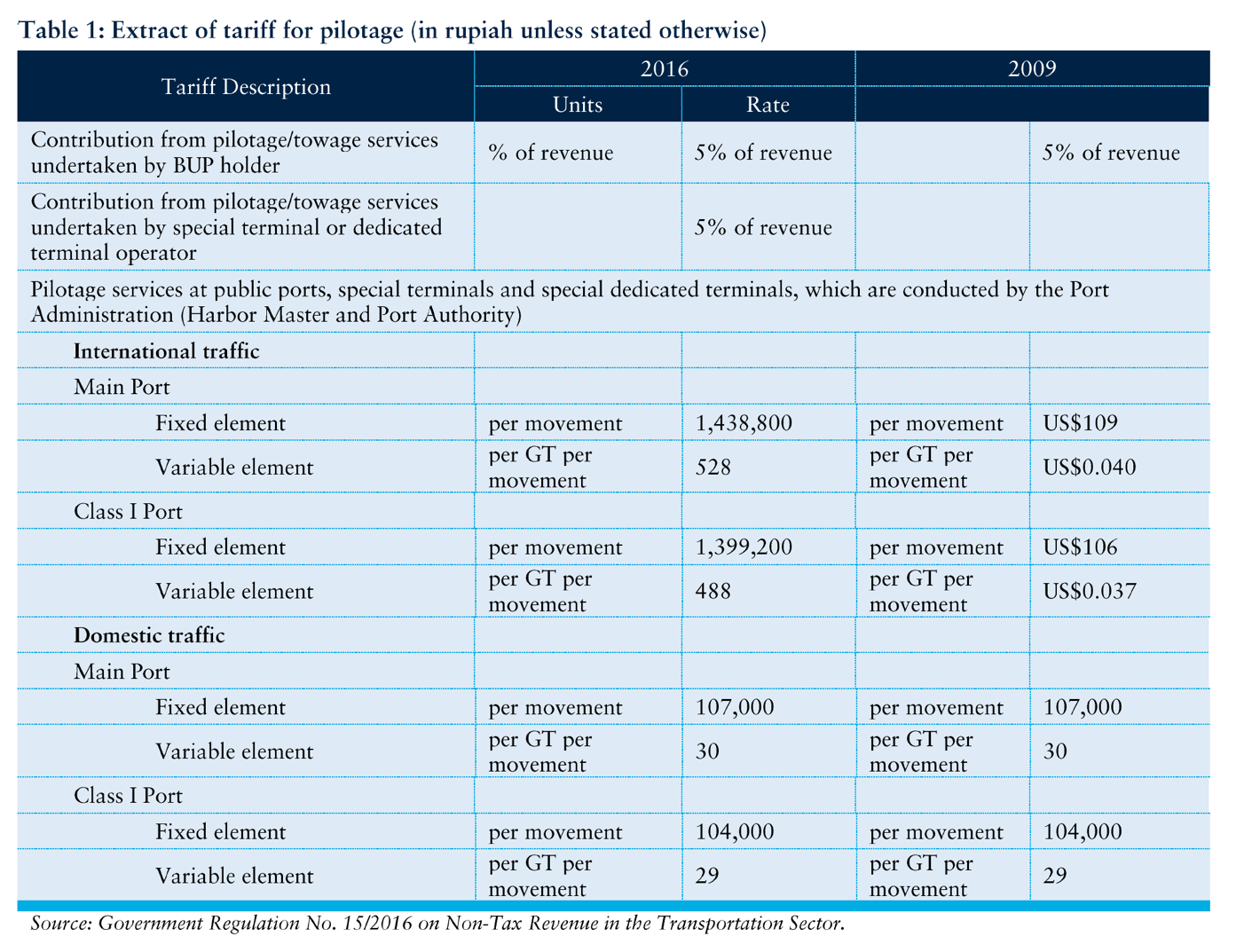

Figure 5 is an extract of the MoT tariff as it refers to pilotage and provides insight into the historic trends in these tariffs. Figure 5 is taken from the IFC study. The key observations to be made from Figure 5 are:

- The ratio of cost between domestic and international ships charges is 1:15 for delivery of the same service

- There has effectively been no change in charges for pilotage over the last 15 years (a period during which inflation has been approximately 240 percent)

Figure 5: Extract of pilotage tariffs (from IFC report)

The conclusions to be drawn from Figure 5 are:

- There is no relation between the cost of delivery of the service and the level of the tariff. Further, either the cost of international pilotage to ships is causing a competitive disadvantage to Indonesian ports because it is too high or there is a very substantial subsidy being provided to Indonesian domestic shipping (alternatively they are receiving a poor service leading to delays and safety concerns)

- It is proving difficult to amend Indonesian port tariffs in line with inflation. This failure to adjust port tariffs is in contrast to the situation in all other G20 countries where the pilotage tariff is adjusted on a regular (usually annual) basis.

Conclusion and recommendations

To deliver port investment across Indonesia the private sector needs incentives to invest. This means that port tariffs must be high enough to provide commercially justifiable returns on their investments in line with best practice. The returns must allow for private-sector risk. Part of that risk is competition with SOEs. So, any successful PPP in the port sector in Indonesia is rooted in a reform of port tariff regulation.

Competition-based tariffs. Based on the example of G20 countries the form of regulation should be reliant on B2B discussions to set the levels of port tariffs, the World Bank (2022) on developing China’s ports confirms this. Alternatively, using experience from a minority of G20 countries, port tariffs should be set through the competition process for new concessions.

Transparent cost recovery. Should ability-to-pay concerns arise, the MoT could consider viability gap funding (subsidies). This could be provided through different mechanisms including capital contributions or operating subsidy payments based on least-cost offers from operators. Transparency is essential in award or payment of any subsidy. Transparency requires clear and accurate cost-recovery calculations and/or open tender for their sizing and award. Neither of these are at present possible.

SOE competition management. The MoT has identified the critical concern that Pelindo, the relevant SOE dominates the port sector in Indonesia and has a broad range of anticompetitive methods through which to resist new market entrants and retain its monopoly. The encouragement and promotion of competitors to Pelindo is therefore a second and equally important policy requirement to support private sector involvement in PPP port projects. Given Pelindo has existing assets and has limited need to invest to deliver the user a service, even if that service is of low utility to the user, maintaining the current tariff policy, structure and levels acts as a strong protective measure. It may depress the returns made by Pelindo but it ensures there is no competition or threat to those returns continuing ad-infinitum.

Infrastructure planning. Tariff reform needs to be complemented by a clear pipeline of projects according to the National Port Master Plan. The private sector may also be able to contribute to project identification. Port developments require 30 to 50 years to mature and deliver their full returns. The private sector will not invest in projects where they do not see long-term sustainable demand.

Reconsider the role of SOEs. Pelindo could play a vital role in the identification and enabling of a clear project pipeline. This would be as a facility developer and commercial landlord rather than terminal operator. There would be strong benefits to Indonesia in clear and effective cooperation between the MoT and Pelindo to combine legal certainty (MoT) with land (Pelindo). This combination would enable port infrastructure developments (terminals) to be awarded to experienced private operators for investment and operation at the highest valuations practical. The structure of New Priok would be an effective blueprint of such cooperation.

References

IFC (2019) Review of Port Tariff Structures and Levels in Indonesia.

World Bank (2022) Aritua, Bernard; Chiu, Hei; Cheng, Lu; Farrell, Sheila; de Langen, Peter. 2022. Developing China’s Ports : How the Gateways to Economic Prosperity Were Revived. International Development in Focus;. Washington, DC: World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/37445 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Badan Pusat Statistik (2021) Statistik Perhubungan Laut – Sea Transport Statistics.

ANNEX 1

Aggregate throughput

Throughput in ‘000 tons

Source: Statistik Perhubungan Laut

Throughput in ‘000 tons aggregated

Source: Statistik Perhubungan Laut

Notes:

- Theoretically domestic loaded and unloaded should be the same.

- International throughput is heavily imbalanced toward exports.

- Export volumes are dominated by coal exports and secondly crude palm oil. Both generate limited cargo-handling revenue per ton.

- Spike in exports between 2010 and 2015 can be explained from a demand boom in commodities, in particular coal.

ANNEX 2

Overview of issued concessions by the Ministry of Transportation

| Concession for port or terminal | Concession fee percent gross Revenue | Term (years) | Operator |

| Pelabuhan Belawan | 2.5 | 30 | SOE |

| Pelabuhan Tanjung Priok | 2.5 | 50 | SOE |

| Pelabuhan Tanjung Perak | 2.5 | 30 | SOE |

| Pelabuhan Makassar | 2.5 | 30 | SOE |

| Container terminal Belawan Phase II 350 m | 0.5 | 70 | SOE |

| Bulk liquid terminal Pelabuhan Juala Tanjung | 2.5 | 69 | SOE |

| Terminal Kalibaru Pelabuhan Tanjung Priok | 0.5 | 70 | SOE |

| Terminal Kijing Pontianak | 2.5 | 69 | SOE |

| Multipurpose terminal Teluk Lamong | 2.5 | 72 | SOE |

| Alur Pelayaran Barat Surabaya | 3.5 | 25 | SOE |

| Container terminal Makassar New Port Phase 1 | 2.5 | 70 | SOE |

| Terminal Cigading Pelabuhan Banten | 3 | 75 | SOE |

| Terminal KCN Marunda | 5 | 70 | SOE |

| Terminal Manyar Pelabuhan Gresik | 2.75 | 76 | SOE |

| Terminal DABN Pelabuhan Probolinggo | 2.75 | 64 | SOE |

| Container terminal Muara Jambi | 5 | 66 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal Marunda Centre | 2.75 | 65 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal Indo Kontainer Pontianak | 5.5 | 61 | PRIVATE |

| STS Taboneo Banjarmasin | 4.5 | 49 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal Pelabuhan Swangi Indah Kotabaru | 5 | 21 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal SAL | 5 | 37 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal Bandar Bakau Jaya Cilegon | 3.5 | 73 | PRIVATE |

| Terminal Lamongan Shorebase | 2.75 | 72 | SOE |

| Terminal Siam Maspion | 2.5 | 43 | PRIVATE |

| STS Mutiara Berau | 5 | 25 | PRIVATE |

Source: compiled by authors

ANNEX 3

Principles of port tariff regulation in G20 countries

| Ports | Regulatory Method | Monopoly Situations | Comments | |

| Argentina | Cap Tariff (by contract in concessions after bidding process) | – | ||

| Australia | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | – | |

| Brazil | Tariff set within concession selection process | – | ||

| Canada | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | – | |

| China | Subject to central control but set to encourage development | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | ||

| France | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| Germany | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| India | Moving from rigid return led regulation to B2B (competition) | – | ||

| Indonesia | Approval from Government subject to agreement from stakeholders | – | ||

| Italy | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| Japan | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| Republic of Korea | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| Mexico | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | – | |

| Russia | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | – | |

| Saudi Arabia | Set by Port Authority | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | ||

| South Africa | Set by Port Authority | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | ||

| Turkey | Tariff set within concession selection process | – | ||

| United Kingdom | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Infrastructure funding by private sector | |

| United States | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Infrastructure funding by private sector or local Government | |

| European Union | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

| Spain (always invited) | B2B (competition) | Subject to competition law | Basic infrastructure funded by Government | |

- Closing of the port of Shanghai in March, April and May 2022 ↑

- Jakarta International Container Terminal (JICT) 49 percent Hutchison, KOJA 49 percent Hutchison, New Priok Container Terminal 1 (NPCT1) 27 percent Mitsui 17 percent PSA. ↑

- Consultation according to Ministry of Transportation decree is in reality a written approval. ↑