There is a significant funding gap hindering the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in developing countries. Philanthropic organizations, therefore, have a unique opportunity to help meet these targets by providing the much-needed additional capital and expertise. However, according to recent data, many global philanthropic initiatives tend to concentrate on middle-income countries and a limited number of SDGs, neglecting low-income countries and other SDGs, compounded by unclear governance frameworks. The Group of Twenty (G20) countries could address these challenges by enhancing meaningful partnerships between governments, philanthropic organizations, and multilaterals to ensure that all SDGs are achieved.

Challenge

Philanthropic funding has reached an unprecedented global scale. In the US alone, seventy-five thousand private foundations have been established since the late 1990s, and over five thousand new ones are founded annually (Johnson 2018). About 75% of the 260 thousand foundations, spread over 39 countries, have been established in the past 25 years. Their assets surpass USD 1.5 trillion and they spend over USD 150 billion annually (Johnson 2018). However, the vast majority—almost 95%—of the global philanthropic organizations are concentrated in Europe and North America (Johnson 2018).

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is critical to ensuring an equitable and environmentally sustainable future for all humankind. Current estimates find that the financing gap for developing countries in achieving the SDGs by 2030, is approximately USD 2.5 trillion (Doumbia and Lauridsen 2019; UN in India 2019). This shortfall offers an opportunity whereby the philanthropic sector could support countries and regions in achieving the SDGs. However, five key challenges emerge when philanthropic contributions to the SDGs are examined.

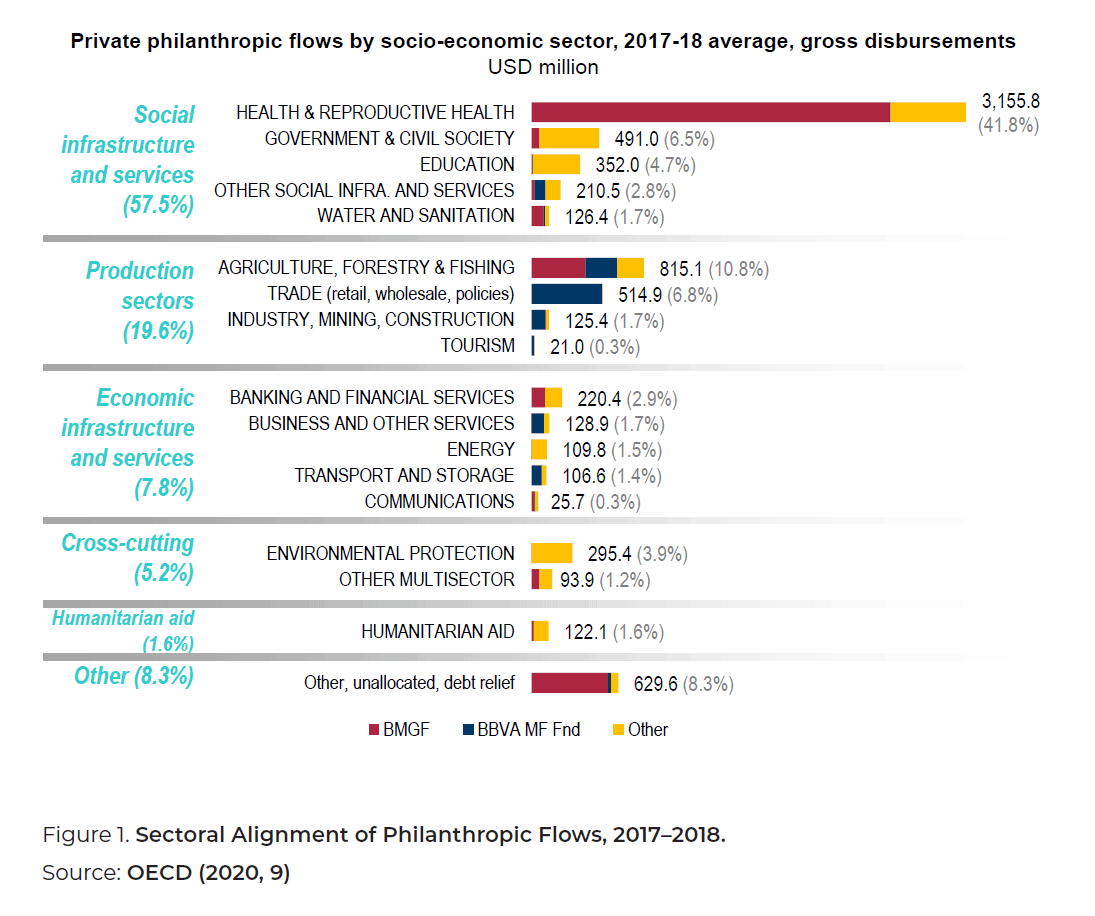

1. Targeting by Sector

Figure 1 illustrates that 57.5% of philanthropic funding is allocated to social infrastructure and services, with 41.8% being allocated to health and reproductive health within the sector alone. This results in not only the comparative neglect of other sectors, such as production (19.6%), economic infrastructure and services (7.8%), and humanitarian aid (1.6%), but also the neglect of other social infrastructure and services, such as education, and water and sanitation.

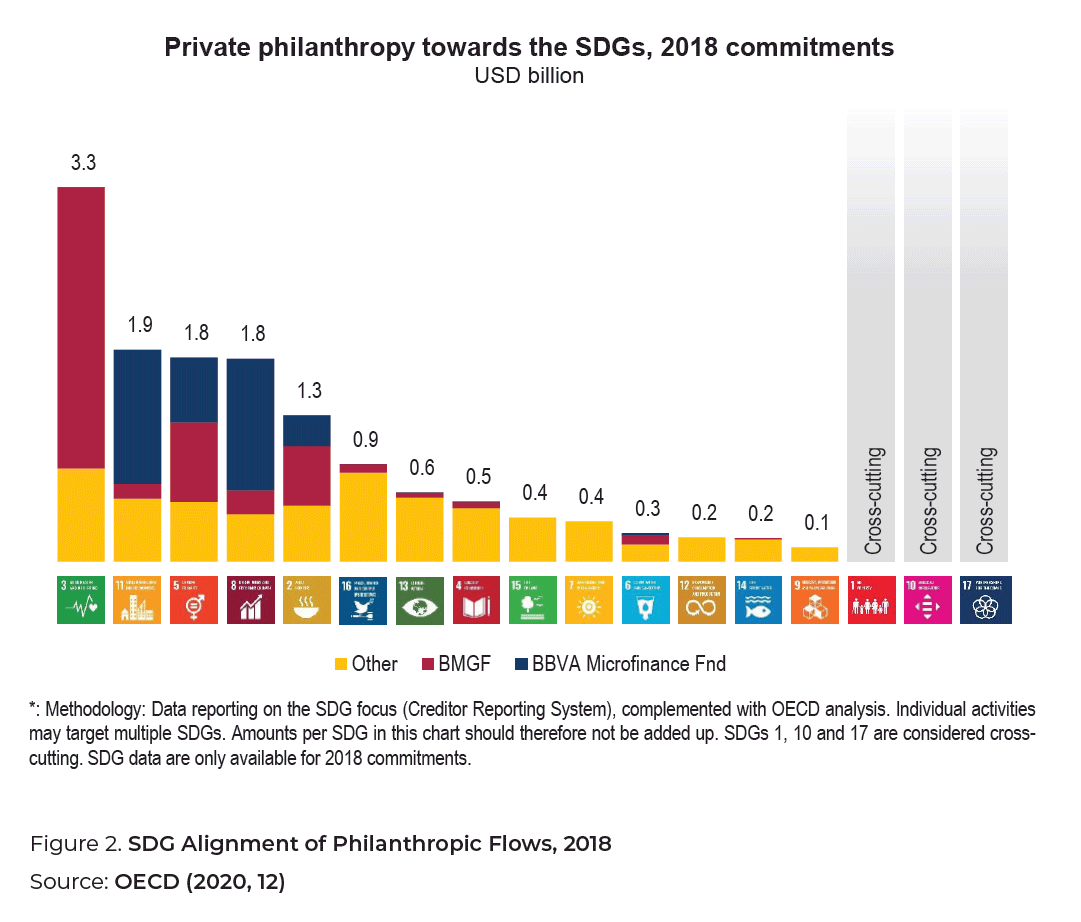

2. Allocation of Funding by SDG

Figure 2 shows that 74% of philanthropic flows in the sample from the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Statistics fall under only five SDGs (OECD 2020). In this regard, 24% of philanthropic funding is allocated to SDG 3 (health and well-being), although seven other SDGs have an even larger funding gap, such as the SDG for education (OECD 2020). Similarly, the allocation of funding varies within each SDG and by country. For example, funding focused on gender equality tends to be concentrated on reproductive health in middle-income countries of Africa and South America, as well as in India, leaving other gender inequality issues unaddressed (OECD 2020).

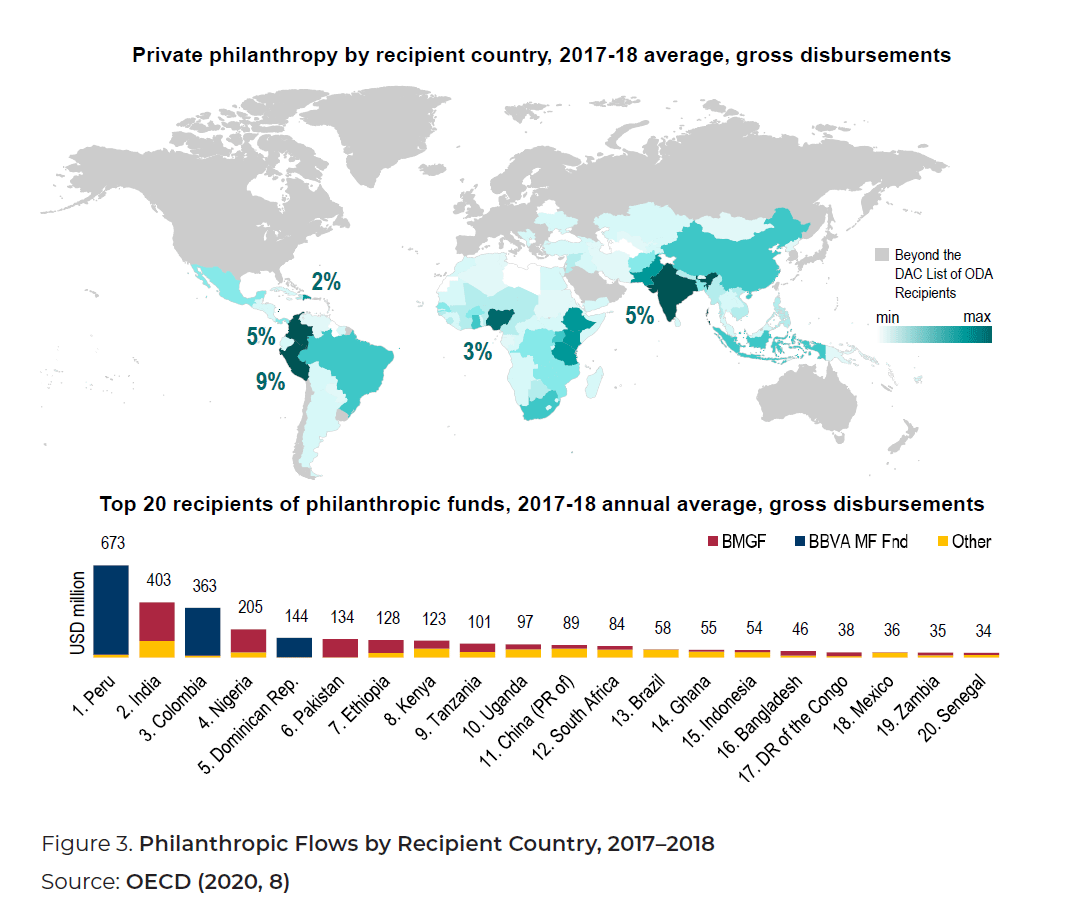

3. Geographic Distribution of Funding

Philanthropic flows currently tend to be directed at middle-income countries and countries in specific regions, neglecting low-income countries and other regions. According to the OECD, middle-income countries receive two-thirds of country-allocable giving, and this difference becomes even larger when considering private philanthropy alone (Sangaré and Hos 2017). In 2017 and 2018, private philanthropy to middle-income countries was approximately USD 2.6 billion per year, while it was only USD 757 million per year to least developed countries (LDCs) and USD 20 million per year to low-income countries (OECD 2020). Over the same period, 24% of philanthropic flows went to five countries, namely Peru, India, Colombia, Nigeria, and the Dominican Republic, while all other countries and regions received comparatively smaller flows (as shown in Figure 3). The reason for the comparatively larger philanthropic fund flows to India has been the presence of a global Indian diaspora and government regulations that promote corporate social responsibility and philanthropy, coupled with the growing economy and middle-class community (Chaturvedi 2019; India Abroad 2019). Several other nations suffer from a lack of capacity to absorb the magnitude of these flows. This could be due to the absence of a strong non-governmental organization system that could help in developing SDG projects and infusing funds.

4. Coordination between Funding Stakeholders

Philanthropic actors are failing to effectively coordinate with other donors, governments, and development stakeholders with regard to the SDGs. This has led to the duplication of initiatives and inefficient use of resources. As a result, philanthropic organizations repeat mistakes, struggle to establish credibility, and are less aware of underserved groups. A report by the World Humanitarian Summit describes philanthropic flows as uncoordinated and ad hoc, highlighting the risks of working in isolation (Webster and Paton 2016). This lack of coordination has led to misinformation and limited understanding of global philanthropic flows, as well as the complexities and specificity of issues in local contexts (Boesso and Cerbioni 2019, Di Lorenzo and Scarlata 2019, Scott 2009, Merz, Peloza, and Chen 2010).

5. Framing Philanthropy to Ensure Good Governance, Transparency, and Accountability

National governments are often the lead actor responsible for providing access to many essential services covered by the SDGs, including quality education, healthcare, and employment support. However, as funding gaps continue to grow, private philanthropy becomes an increasingly influential actor at the local, national, and international levels across various public domains addressed by the SDGs. Currently, there is little agreement on how philanthropic organizations fit into the public services landscape with other non-state actors, and on how they should be regulated (Srivastava 2020); this is further complicated by the lack of a common global language with local definitions. The lack of a common regulatory framework and definitions for the work of the philanthropic sector makes coordination across the sector difficult for all stakeholders. Additionally, transparency and accountability mechanisms to monitor organizations’ activities are less feasible if institutional arrangements, decision-making mechanisms, and risk sharing are unclear. As a result, stakeholders supporting the SDGs may face difficulty in effectively targeting sectors, allocating funding to address local needs, and supporting communities in achieving the SDGs.

Proposal

“Because for prosperity to be sustained, it must be shared.”

G20 Seoul Summit, Annex I

Leveraging and engaging with private philanthropy provides opportunities for the G20 member states to develop partnerships that contribute to achieving the SDGs. Although the relationship between the philanthropic sector and government is complex (Moran 2014), the G20 countries have a key role to play in establishing a clear direction, framework, and ethos for the sector. This would help leverage trillions of dollars of private funds to create long-term positive impact. Such engagement is critical for ensuring better coordination among stakeholders, so that the initiatives are tailored and targeted towards those geographic and thematic areas that are critical for reaching the targets set by the SDGs. In addition, leveraging private philanthropy would allow the G20 countries to strengthen the critical SDG 17 on seeking partnerships between the public and private sectors, as philanthropic organizations are core parts of such collaborations (Ogden, Prasad, and Thompson 2018).

We propose five broad policy recommendations for the G20 countries to effectively leverage private philanthropy towards achieving the SDGs:

1. Philanthropic organizations must take a local approach in supporting the SDGs

Many actors in the development sector continue to duplicate projects that address the same SDGs, while neglecting the targets of other SDGs (Reckhow and Snyder 2014). These must be purposefully targeted in order to address such gaps. This effort should be further complemented by the identification of priority areas, based on the needs of the local community, as well as national and regional contexts.

Policy Recommendation 1.1

The G20 countries should foster stronger and closer coordination between the philanthropic sector, local governments, and experts. Information is crucial for facilitating a local approach. Philanthropic actors and all stakeholders should begin liaising with local governments before starting a project. This will allow local governments to identify areas in greater need. It will also facilitate information exchange between local experts, other actors, and central governments. Over time, this information will help to develop a system of documenting previous experiences to ensure that similar projects are not repeated, while also offering the potential to share lessons learned. This could be further complemented by ensuring more robust monitoring and evaluation of development projects and their implementation at the local level. In addition, local governments should be encouraged to coordinate between funders and local experts to facilitate information exchange, so that projects are better adapted to local contexts.

Policy Recommendation 1.2

The G20 should promote the cross-mapping of development projects with local needs and the SDGs. Using information from local development projects is a key element for local governments. This facilitates the cross-mapping of community needs based on their own knowledge and those based on the knowledge of local experts. This information should then be analyzed to determine how local development projects are meeting the needs of the local community, using the SDGs as indicators. This will enable philanthropic actors and governments to identify which projects should be prioritized, based on the SDGs that need more support for a given community. This will also help to identify those actors that are failing to attract donors and lack community support, but might be critical for the long-term success of the SDGs. For example, access to early childhood education and care centers might not be high on the agenda of a local community in the initial stage, but will be very helpful as the community matures and seeks to achieve all SDGs. Developing capacity early on for such communities, would subsequently enable the creation of future social infrastructure.

Policy Recommendation 1.3

The G20 member states must encourage philanthropic donors to assist in creating a platform that aggregates national information on local actors’ projects and partners. In addition to collecting information, it is essential to provide updated and accessible information through an open online platform that could be created for a country or a region. This would help to reduce the burden on a country with fewer resources and enable the sharing of resources, while also ensuring communication of the lessons learned during implementation. The platform must allocate projects and resources, using the SDGs as indicators. Information should be standardized, as it would facilitate cross-country comparisons and the development of regional indicators to identify which countries, regions, and projects need to be prioritized. Such a platform could be further supported and maintained by international organizations, such as the OECD or UNDP. Currently, several platforms are being developed; however, the existing platforms lack information on local needs and are missing significant portions of fund flows globally, with large variations across regions (see for example, Candid 2020; SDG Philanthropy Platform 2020). These are not as comprehensive as our proposed platform that would provide a single access point for governments, funders, and development actors to quickly access the key information needed before, during, and after engaging in a project. Online availability of data would also foster the much-needed transparency in data for SDG implementation, enabling communities to track the projects in their communities, thus diluting the perceived political nature of developmental assistance.

2. Prioritize philanthropic funding for the neglected SDGs

Given the prevailing gap in the funding needed to achieve the SDGs, it is essential to mobilize the private philanthropic sector to harness further funding, innovation, transparency, and flexibility. Funding must be allocated efficiently, prioritizing the neglected SDGs based on their funding gaps. Funding should be reallocated in order to avoid an uneven and skewed distribution to the detriment of the least funded SDGs (as highlighted earlier). This could enable more efficient gap reduction.

Policy Recommendation 2.1

The G20 countries should encourage philanthropic organizations to disclose their financial statements and reports. Financial information is needed not only to improve transparency and accountability in the philanthropic sector, but also to design better funding allocation. Nevertheless, many foundations and philanthropic actors do not disclose their finances and other information regarding funding allocation at the project level, within their portfolios (Ridge, Kippels, and Bruce 2019). The lack of information undermines the efforts towards calculating and allocating the available global resources, including official development assistance. The G20 countries should work with philanthropic entities around the world to disclose this information to governments, and enable its access. This would help all stakeholders to identify which SDGs and regions to prioritize.

Policy Recommendation 2.2

The G20 countries must promote cross-mapping between philanthropic funding and the SDGs. Availability of financial information from private philanthropy, governments, and non-state actors enables the cross-mapping of these flows with the SDGs. However, it is also essential that this information be made accessible. This information could therefore, be integrated with the aforementioned online platform, providing a complete picture of how and where philanthropic flows are being used. This will enable all development actors to identify those areas under the SDGs that are being neglected, and determine how to better direct philanthropic flows to meet local needs.

Policy Recommendation 2.3

The G20 countries and leading philanthropic organizations should incentivize the funding of the neglected SDGs. In addition to demonstrating which program areas need increased funding to ensure achievement of the SDGs, the G20 countries and development donors can incentivize other funders to prioritize projects that fall under the purview of those SDGs that are most in need. This can be achieved by designing projects addressing the neglected SDG areas and providing incentives for other funders. For example, private philanthropy could support these projects by either matching their funding, providing in-kind support, or by offering other incentives for supporting these high-priority projects. This process can be further promoted by complementing this funding approach with the online platform. Thus, similar projects are matched together, thereby enabling the sharing of resources and the achievement of economies of scale that some of these projects would require. For example, rural sanitation and drinking water projects could be paired together to provide local communities with a single SDG project addressing two different SDG outcomes, thus ensuring that the project is successful.

3. Develop better coordination initiatives to fully leverage philanthropic funding

Numerous funders are currently involved in the SDGs—bilaterals, multilaterals, and private philanthropy—operating within echo chambers, independent of one another, with limited coordination. The G20 countries should promote better coordination among various stakeholders by creating spaces that include all types of funders (the public, private, and development sectors). Stakeholders should work in two different directions that need to be better integrated:

- Horizontally: Governments, philanthropic organizations, the private sector, and unions must be included. Collaborations become stronger if agreement is established among different sectors and types of actors.

- Vertically: Better coordination can be achieved if, rather than working as gatekeepers, large philanthropic organizations include smaller organizations (generally local), as well as wider organizations (larger organizations and multilaterals).

Horizontal and vertical agreement will ensure better coordination, allowing for more inclusive and efficient funding allocation, as well as better informed decision-making.

Policy Recommendation 3.1

The G20 countries should promote spaces where SDG priorities are presented to potential philanthropic funders. Creating platforms for all funders and stakeholders working in the development sector is essential to ensure greater inclusion. G20 events and other national and regional events could work with other side events led by governments and engagement groups, on philanthropic opportunities and challenges in supporting the SDGs.

Policy Recommendation 3.2

The G20 countries must ensure partnership sustainability when addressing the SDGs. Development projects implemented by philanthropic funders should be strengthened by involving a wide range of stakeholders. This aims at reducing risks for all involved actors (the local communities, governments, philanthropic organizations, international agencies, and others), as well as ensuring long-term commitment.

Policy Recommendation 3.3

The G20 countries should develop and implement a regulatory framework to coordinate philanthropic activities among local stakeholders. Stronger community consent and inclusion could be achieved by establishing frameworks involving local stakeholders and philanthropic organizations. This would enable aligned and co-created activities based on all stakeholders’ interests, especially those from local communities. Such a framework would not only ensure that a more diverse set of views are present on a project, but also enable better allocation according to the stakeholders’ experience, know-how, and commitment possibilities. In this regard, all stakeholders must identify the strengths and weaknesses of each actor and formulate detailed plans for the distribution of responsibilities that may be related to advocacy, implementation, and development of local capacity, research, and evaluation.

4. Address geographic and income-based country-biased gaps

Private philanthropy is usually focused on middle-income countries and specific regions. This implies that many other countries at risk of not achieving the SDGs, are overlooked. It is, therefore, essential that the G20 countries work towards better addressing geographic, and income and country-biased gaps. The G20 could also help in ensuring that projects are tailored to specific contexts, by including local stakeholders and addressing the needs of the local community.

Policy Recommendation 4.1

The G20 should incentivize philanthropic funding in high-needs regions and countries, especially in LDCs. The G20 countries have a key role in encouraging philanthropic funders to target those regions and LDCs that are most in need. In this regard, our previous recommendations addressing local approaches and better coordination could be the key drivers to promote incentives among stakeholders. For example, actors in those countries and regions could incentivize other funders to partner with them by providing matched funding or in-kind support. This could be further complemented by prioritizing high-needs regions and countries on a global platform and integrating a partnering mechanism to create a market exchange for the provision of funding and in-kind support for development projects.

Policy Recommendation 4.2

The G20 countries should advocate for the SDG indicators to include statistics on trends in countries, grouped by income level or region, in all United Nations SDG reports. Greater effort among the G20 countries and multilaterals should be made, to include statistics on the SDG indicators that could be used to examine regional trends, as well as trends for various groupings of countries, such as by income level. This would highlight any systematic disparities and help identify which regions and countries should be prioritized.

5. Provide a clear global framework and common language for private philanthropy that recognizes local needs

Private philanthropy has been increasingly involved in supporting essential services, such as access to quality education, healthcare, and employment, but with varying degrees of transparency and accountability. The G20 countries could support the sector through the development of a common language defining the work of private philanthropy, as well as an international framework to promote good governance across the philanthropic sector. While philanthropic activities must be local in nature, much of the regulatory framework for philanthropic actors can and must be developed at the global level. This will not only be more efficient for the G20 countries, but also enable better coordination, allocation, and sectoral targeting, because information will be more reliable and better aligned across regions for comparability.

Policy Recommendation 5.1

The G20 countries should promote collaboration to develop a framework for philanthropic organizations participating in public services at the global level. This framework must seek to build common regulations in terms of contracting, partnerships, and financing. These regulations will provide better guidelines to ensure mechanisms for transparency and accountability, as well as governance structures, particularly in essential social services, such as health, education, and employment, all of which have spillover effects across the SDGs.

Policy Recommendation 5.2

The G20 countries should advocate for a common global language to be used across the development sector, to facilitate better coordination with private philanthropy. The development of a common global language, with local definitions for philanthropic activities, is essential to ensure that the data on these activities are reliable and accurate, regardless of who the actors are, or where they are operating. The definitions should cover the areas of contracting, partnerships, financing, programmatic activities, regulations, and management. This will provide a clear understanding of the current activities of private philanthropy as they relate to the SDGs, and enable priority areas to be identified.

Policy Recommendation 5.3

The G20 countries should advocate for data production on philanthropic activities at the global level. Given that philanthropic actors often operate across international borders, comprehensive data on the activities of the philanthropic sector at the local level will require coordinated efforts at the global level. Although the effort has been made by multilaterals, there is an urgent need for comprehensive information on private philanthropy with regard to the actors, investment levels, providers, programmatic activities, and recipients. This would help to facilitate better coordination, sectoral targeting, and funding allocation on a global scale.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Boesso, Giacomo, and Fabrizio Cerbioni. 2019. “Social Role, Strategic Profiles and

Management Tools of Foundations.” In Governance and Strategic Philanthropy

in Grant-Making Foundations, 1–43. New York: Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16357-0_1.

Candid. 2020. “SDGfunders.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://sdgfunders.org/home.

Chaturvedi, Anumeha. 2019. “India Maintains Strong Philanthropic Momentum: Bain

and Company.” The Economic Times, March 19, 2019. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/company/corporate-trends/india-maintains-strong-philanthropic-momentum-bain-company/articleshow/68332136.cms?from=mdr.

Di Lorenzo, Francesco, and Mariarosa Scarlata. 2019. “Social Enterprises, Venture

Philanthropy and the Alleviation of Income Inequality.” Journal of Business Ethics

159, no. 2: 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4049-1.

Doumbia, Djeneba, and Morten Lykke Lauridsen. 2019. “Closing the SDG Financing

Gap—Trends and Data.”EM Compass Notes: Fresh Ideas About Business in Emerging

Markets, no. 73. International Finance Corporation (IFC). Accessed July 20, 2020.

https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/842b73cc-12b0-4fe2-b058-d3ee75f74d06/EMCompass-Note-73-Closing-SDGs-Fund-Gap.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mSHKl4S.

India Abroad. 2019. “How NGOs Play an Important Role in India’s Development.” India

Abroad, December 17, 2019. Accessed July 20, 2020. https://www.indiaabroad.com/special_reports/how-ngos-play-an-important-role-in-india-s-development/article_7e160612-212d-11ea-a8e5-17a241c7e386.html.

Johnson, Paula D. 2018. Global Philanthropy Report: Perspectives on the Global

Foundation Sector. Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School, The Hauser Institute for

Civil Society at the Center for Public Leadership. Accessed July 20, 2020. https://cpl.hks.harvard.edu/files/cpl/files/global_philanthropy_report_final_april_2018.pdf.

Merz, Michael A., John Peloza, and Qimei Chen. 2010. “Standardization or Localization?

Executing Corporate Philanthropy in International Firms.” International

Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 15, no. 3: 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.386.

Moran, Michael. 2014. Private Foundations and Development Partnerships: American

Philanthropy and Global Development Agendas. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315855585.

OECD. 2020. Private Philanthropy for the SDGs: Insights from the Latest OECD DAC

Statistics. Accessed January 20, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/beyond-oda-foundations.htm.

Ogden, Kim, Sridhar Prasad, and Roger Thompson. 2018. “Philanthropy Bets Big on

Sustainable Development Goals.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, September 18,

2018. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/philanthropy_bets_big_on_sustainable_development_goals#.

Reckhow, Sarah, and Jeffrey W. Snyder. 2014. “The Expanding Role of Philanthropy

in Education Politics.” Educational Researcher 43, no. 4: 186–195. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14536607.

Ridge, Natasha Y., Susan Kippels, and Elizabeth R. Bruce. 2019. “Education and

Philanthropy in the Middle East and North Africa.” In Philanthropy in Education: Diverse

Perspectives and Global Trends, edited by Natasha Y. Ridge and Arushi Terway,

70–89. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789904123.

Sangaré, Cécile, and Tomas Hos. 2017. Global Private Philanthropy for Development:

Results of the OECD Data Survey as of 3 October 2017. Paris: OECD. Accessed July

20, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/Philanthropy-Development-Survey.pdf.

Scott, Janelle. 2009. “The Politics of Venture Philanthropy in Charter School

Policy and Advocacy.” Educational Policy 23, no. 1: 106–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904808328531.

SDG Philanthropy Platform. 2020. “Our Work: What We Do.” Accessed July 20, 2020.

https://www.sdgphilanthropy.org/About-SDGPP.

Srivastava, Prachi. 2020. Framing Non-State Engagement in Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Accessed July 20, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000372938.locale=en.

UN in India. 2019. “Financing the SDGs.” Accessed July 7, 2020. https://in.one.un.org/un-speech/financing-the-sdgs.

Webster, Regine A., and William Paton. 2016. The World Humanitarian Summit: A

Pivot Point in Philanthropy’s Contribution to Addressing Humanitarian Crises. New

York: UNDP, SDG Philanthropy Platform. https://www.sdgphilanthropy.org/system/files/2018-01/The_World_Humanitarian_Summit_-_A_Pivot_Point_in_Philanthropy’s_Contribution_to_Addressing_Humanitarian_Crises.pdf.