Over the past five years, investment screening has gained in prominence as a policy tool. The COVID-19 pandemic has once more accelerated this trend. Investment screening is a justified policy instrument to protect national security and public order. However, an overly broad interpretation of these interests, an increasing number of covered sectors, and opaque decision-making could create new investment barriers and distort worldwide investment flows. This policy brief aims to provide an overview of screening mechanisms in G20 countries, the criteria that trigger the screening process, the covered sectors, and designated thresholds. This is to help provide a basis for the G20 to deal with investment screening by establishing comparisons and best practices.

Challenge

Countries benefit greatly from the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) in terms of technology transfer, job creation, innovation and economic growth. But FDI can also become a risk to national security and public order – at least, more and more governments around the world believe this to be the case. Over the past five years, investment screening has gained in prominence as a policy tool, particularly in developed G20 countries, including Australia, Canada, Germany, the European Union, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, global FDI fell by 42 per cent in 2020 according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The decrease in investment flows was particularly felt in the developed countries, which experienced a drop of 69 per cent, while developing countries experienced a drop of 12 per cent (UNCTAD, 2021). This has not stopped many countries from once more tightening their investment screening laws and regulations. For example, many countries have lowered their foreign ownership thresholds for screening, and more and more sectors of the economy are considered critical. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), more than 50 per cent of investment flows today are potentially subject to screening under cross-sectoral mechanisms – in the 1990s it was less than 30 per cent (OECD, 2020b). Investment screening has gained in acceptance not only among policy-makers but also within the business community, and the line between investment screening in the interest of national security and industrial policy is blurring.

The driving factors behind this development are geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts, in particular the rise of China. The world’s economic centre of gravity (WECG) is moving. While it was located in the Atlantic Ocean until 2007, by 2030 the WECG could be located around the confluence of China, India and Pakistan, according to computer simulations by Euler Hermes (Euler Hermes, 2021). This trend is accelerating as the Asia-Pacific region, and particularly China, is recovering faster from the COVID-19 crisis than other regions of the world. While China’s outbound investment has decreased since 2016 after a decade of double-digit growth (Kratz et al., 2020), this has not eased fears in many developed countries that China is strategically buying critical assets (technologies and infrastructure) abroad. Four years of US President Donald Trump and the US–China conflict have driven a trend towards securitization of trade and investment policy in the developed countries. In other words, trade and investment are more and more viewed from a security perspective.

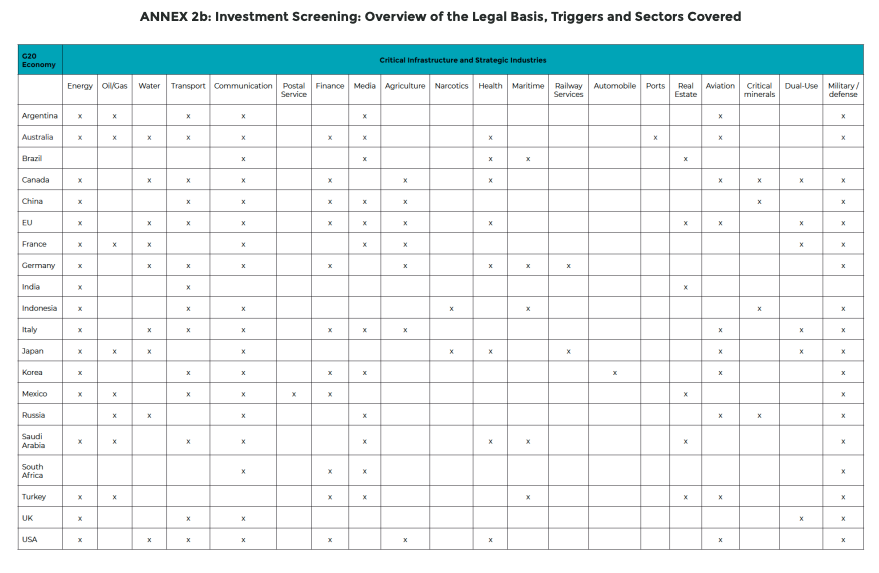

Another driving factor is the development of new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, 5G, quantum technology, nanotechnologies, biotechnologies and satellites. These are a key factor for the international competitiveness of countries. Not only are many of these technologies seen as critical to national security, but many governments regard them as vital for competitiveness (UNCTAD, 2019).

Most recently, as health product value chains have come under enormous stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many governments have made investment in the health sector subject to investment screening (e.g. in France, Germany and Japan). The production of medical goods and pharmaceuticals is increasingly viewed as critical to a country’s national security and public order. Furthermore, fears have grown in many countries that foreign investors could use the crisis to buy up companies in financial distress.

Investment screening is nothing new and serves as an important policy tool to ensure public order and security. At the same time, there is a fine line between national security interests and economic protectionism. Opaque rules and procedures as well as uncoordinated approaches could easily become a new investment hurdle, with negative consequences for economic growth and development worldwide.

Proposal

DIFFERENCES AND COMMONALITIES IN INVESTMENT SCREENING

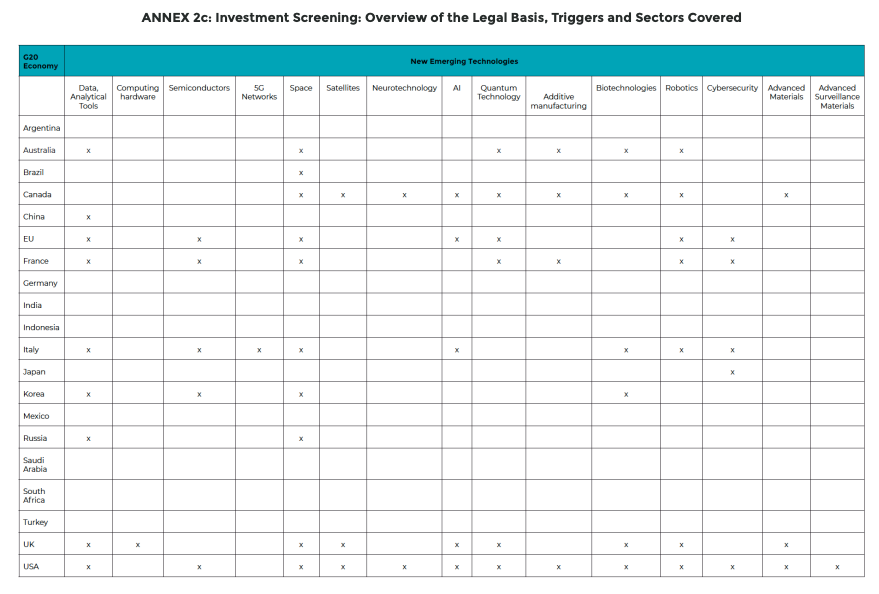

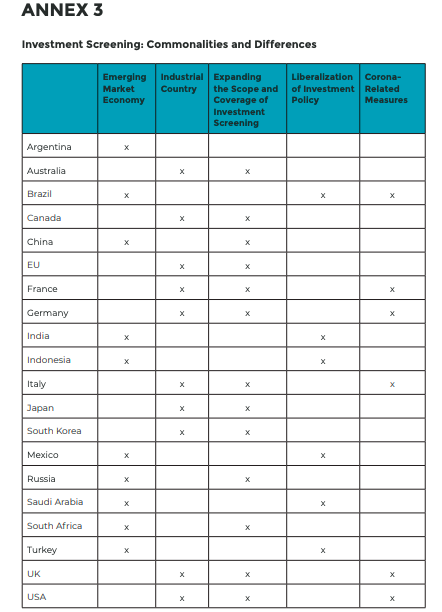

Not all G20 countries have stand-alone investment screening mechanisms. Those which have such mechanisms are Australia, Canada, China, the EU, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Korea, Russia, South Africa, the UK and the United States. Those G20 countries that do not have such a mechanism often control inward investment through other means, mostly sector-specific provisions.

The current resurgence of investment screening is driven largely by developed countries – countries which are characterized by a high degree of investment openness. In the developing countries, investment screening was a widely used policy tool prior to the 1990s. In the course of shifting towards greater openness for trade and investment, many emerging economies not only dismantled requirements for screening and approval, but now see FDI as indispensable for economic growth and development. However, investment openness is still considerably lower in emerging economies than in the developed nations of the G20, with investment restrictions for certain sectors or investment caps, that is, limits on investment in certain sectors.

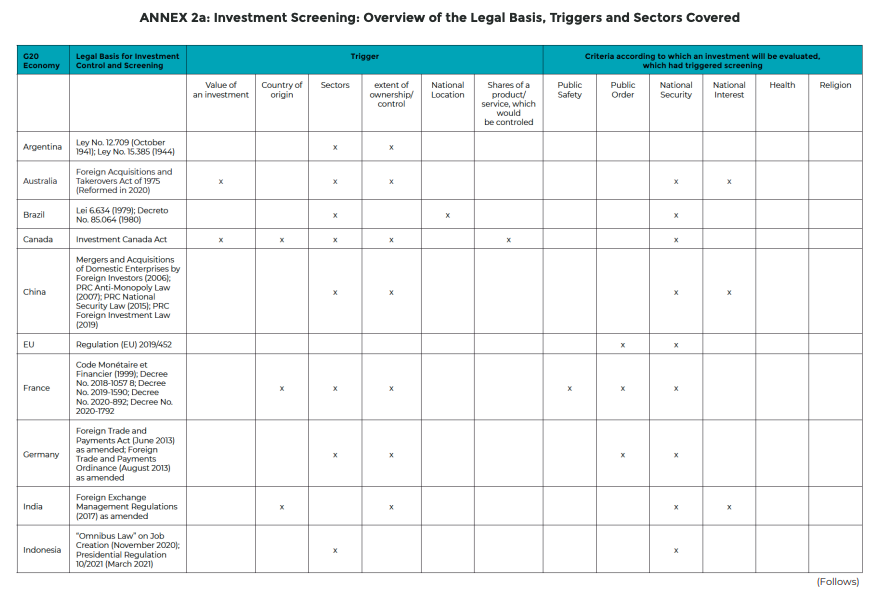

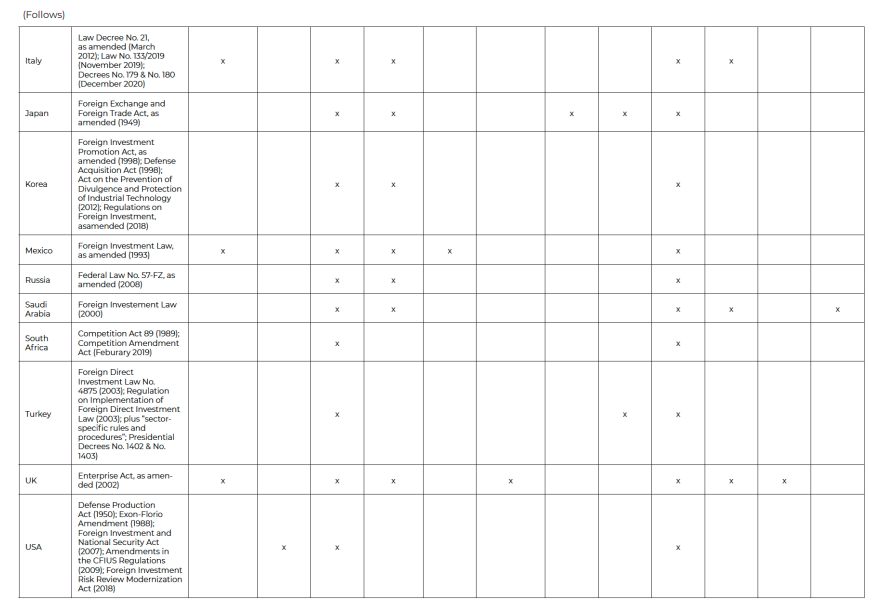

The following sections give a brief overview of current developments in those G20 countries which have stand-alone investment screening mechanisms (the G20 countries with no stand-alone mechanisms are listed in the Annex (A1)). Table A2 in the Annex supplements this overview. Furthermore, Table A3 also offers summaries for those countries which do not have stand-alone mechanisms but nonetheless control investment flows.

Stand-alone investment screening mechanisms in G20 industrialized countries

Australia: In December 2020, Parliament passed legislation to reform the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act of 1975. The new national security test, which has been in force since January 2021, makes the notification of investments in national security land or a national security business mandatory. The screening mechanism provides for a last resort power, which permits the Treasurer to impose new or vary existing conditions, or require the divestment of any approved investment, when national security risks emerge. The criteria for the screening process include safeguarding national security and sovereignty, upholding Australia’s international reputation and relationships, preventing economic damage, and safeguarding critical infrastructure. Critical sectors include, among others, defence, telecommunications, information technology (IT), data and ports.

Canada: The primary mechanism for reviewing foreign investment in Canada is the Investment Canada Act (ICA). Under this law, the government can block a proposed investment, impose conditions (pre- or post-implementation) or order the divestiture of an implemented investment. Investment screening is triggered if non-Canadian investors aim at acquiring control of an existing business or want to establish a new unrelated Canadian business. The aim of the law is to ensure that an investment is of net economic benefit and to review investments that could impair national security. Criteria include the potential effect on the country’s defence capabilities and interests; the impact on sensitive technology or know-how; and the potential impact on the supply of critical goods and services, on critical minerals and their supply chains, on the security of critical infrastructure and on access to personal data.

China: The National Security Review (NSR) was first created under the Provisions on Mergers and Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors (in 2006). Since then, the mechanism has been reaffirmed as well as modified several times. The Measures on National Security Review of Foreign Investments (FINSR) (2020) are designed to mitigate the negative impact of foreign investments on the country’s national security. The screening mechanism is triggered if the investment is made in defence-related sectors or in regions where there are military facilities or military infrastructures, or in “important” sectors. The latter refer, among others, to agricultural products, energy and resources, large manufacturing equipment, infrastructure, transport services and IT. Another trigger is control over the entity in which the investment is made. Control is specified in three ways: (i) the foreign shareholder will hold 50 per cent or more of the interest in the proposed investment entity; (ii) the share is less than 50 per cent but the voting rights of the investor could significantly influence decision-making; or (iii) the investor will otherwise be able to significantly influence business decisions.

European Union: The EU’s FDI Screening Regulation of 2017 put in place an EU-level mechanism to coordinate the screening of foreign investments likely to affect the security and public order of the Union and its member states. At the centre stand critical infrastructure and critical technologies. The mechanism obliges EU member states to exchange information and gives the Commission and member states the right to issue opinions and comments on specific transactions. In the future, member states are to take due account of comments and opinions from other member states. The final decision regarding an investment, however, remains the sole responsibility of the member state in which the investment is planned or has been completed.

France: The basis of investment screening is the Code Monétaire et Financier – FDI Screening law from 1999. In November 2018, Decree No. 2018-1057 expanded the scope of the foreign investment regulation to the “sectors of the future”, making them subject to prior approval (including space operations, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors and additive manufacturing). In December 2019, Decree No. 2019-1590 lowered the threshold from 33.33 per cent to 25 per cent. The decree of 27 April 2020 added biotechnology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In July 2020, Decree No. 020-892 temporarily lowered the threshold that triggers a review of foreign acquisitions from 25 per cent to 10 per cent. On 28 December 2020, Decree No. 2020-1729 extended this requirement from 31 December 2020 until 31 December 2021. Three triggers apply: (i) origin of the investor; (ii) nature of investment operation; and (iii) sensitive activities of the targeted company. The criteria for screening are public order, public security and national defence.

Germany: The legal basis for FDI screening in Germany is the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (AWG) as of June 2013 and the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance (AWV) as of August 2013. There have been several adaptations, the latest in 2021. Investment screening has been tightened in terms of both triggers and criteria. Investment screening is triggered for investment in non-defence sectors that are listed and specially protected if the acquisition leads to control of more than 10 per cent of the voting rights or assets in a German company. In other non-defence sectors (i.e. those that are not listed), acquisitions of 25 per cent of the voting rights or assets in a German company by foreign investors can also be subject to review if public order or public security is affected. The 2020 reform of the AWG broadened the screening criteria. The adaptation of the AWV in 2021 listed several sectors/critical technologies, such as artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, biotechnology and quantum technology.

Italy: The legal basis for investment screening is Law Decree No. 21 of 15 March 2012, as amended. Accordingly, the government can review transactions that relate to either “strategic activities” in the defence and national security sector or “assets with strategic relevance” in certain specific sectors. Criteria are national security and other public interests. Several laws and decrees followed, extending the number of sectors subject to revision, the latest being in 2020. In December 2020, the scope of the “strategic assets and activities” was significantly modified and clarified: Decrees no. 179 and 180 list several sectors as strategic, including defence and homeland security, energy, transport, communication, healthcare, financial infrastructure and artificial intelligence (New Strategic Sectors). The criteria for investment screening are defence interests, national security, essential interests of the state and public order.

Japan: The legal basis for investment screening in Japan is the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, as amended. For certain designated business sectors, prior notification for FDI is necessary. Japan amended its investment screening in 2020. As such, the threshold for Stock Purchases (PN-SP) with regard to the acquisition of a listed company’s stocks was lowered from 10 per cent to 1 per cent. The criteria for investment screening are national security, public order, public safety and smooth operation of the economy.

Mexico: FDI is regulated by the Foreign Investment Law of 1993. That law has been amended several times. The law established the National Registry of Foreign Investment, to which every foreign investment needs to be reported. Generally, FDI is authorized without restrictions, unless the Foreign Investment Law expressly includes a limitation or prohibition. In these cases, the National Foreign Investment Commission is tasked with evaluating foreign investments. Economic sectors, in which foreign investment is completely prohibited, are classified as “activities reserved to the Mexican State” or “activities reserved to Mexicans”.

Russia: The basis for Russia’s investment screening related to national security concerns lies in Federal Law No. 57-FZ on “Procedures for Foreign Investments in the Business Entities of Strategic Importance for Russian National Defense and State Security”, as amended, from 2008. Since 2008, the screening mechanism has been changed with regard to the sectors covered as well as the limit on acquisitions (OECD, 2020a). In July 2017, Russia introduced a general foreign investment screening mechanism. The Government Commission on Control over Foreign Investments is entitled to initiate a review of any transaction by a foreign investor in a Russian company in order to ensure national defence and state security. In July 2020, even temporary foreign acquisitions of voting stakes in strategic companies were subjected to FDI screening procedures. The Russian Federation lists almost fifty sensitive sectors that are relevant for defence and security issues. Government approval is generally required for control of up to 25 per cent of the shares.

South Africa: The Competition Amendment Act (February 2019), which amended the Competition Act 89 of 1998, established a new process for reviewing national security issues arising from FDI. The process includes a review by a presidentially appointed foreign investment committee (FIC) on transactions that may have an adverse effect on national security interests. The provisions relating to the new process have yet to be implemented and the president stil has to identify a list of national security interests the committee must consider. However, the country already regulates FDI in strategic industries through sectoral regulation, including banking, insurance, broadcasting and telecommunications sectors. In determining what constitutes national security interests, the president must consider several factors, including the potential impact on defence, the transfer of sensitive technology, the security of infrastructure, the supply of critical goods, international interests, and the economic and social stability of the Republic.

South Korea: The country has three different investment screening mechanisms for different kinds of threats to its security interests. Firstly, the Foreign Investment Promotion Act (FIPL), the related Enforcement Decree of the Foreign Investment Promotion Act (1998, amended) and the Regulations on Foreign Investment (as amended in June 2018) established a scrutiny mechanism for critical sectors. Secondly, the Foreign Investment Promotion Act, together with the Defense Acquisition Programme Act, established a mechanism in 1998 which requires government approval when investing in defence industries. Thirdly, under the Act on the Prevention of Divulgence and Protection of Industrial Technology, a mechanism was established in 2012 which reviews FDI in national core technology whose development was co-funded by the government (OECD, 2020a). In February 2020, the latter act was further tightened: FDI in national core technologies now always needs prior government approval. According to the three screening mechanisms, the screening triggers are critical industries, national security and national core technologies.

United Kingdom: The government’s powers to scrutinize transactions on national security grounds are defined in the Enterprise Act 2002, as part of the UK’s merger control regime. The law allows the government to intervene in mergers and takeovers on four specified public interest considerations: national security, media plurality, financial stability and to combat a public health emergency. Once the merger notification thresholds are met, the UK government can intervene on public interest grounds. In 2018, the UK lowered the thresholds that trigger investment screening from £70 million to £1 million in high-tech industries. In June 2020, section 58 of the Enterprise Act 2002 was amended to specify an additional ground of intervention: “the need to maintain in the United Kingdom the capability to combat, and to mitigate the effects of, public health emergencies”. A further reform bill was passed in 2021.

United States: The main legal basis is the 1950 Defense Production Act, the 1988 Exon–Florio Amendment, the 2007 Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA) and the amendments in the 2009 Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) regulations. The investment screening process was significantly reformed by the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) in August 2018, expanding CFIUS’s jurisdiction to include stand-alone acquisitions, leases or concessions of real estate in certain instances, as well as “covered investments”. The law requires mandatory filings with CFIUS for certain transactions involving foreign government ownership and so-called TID US businesses (businesses involved with critical technology, critical infrastructure and sensitive personal data). U.S. decision-making on investment control is guided by the criteria of national security, including homeland security issues. The law and subsequent presidential directives and regulations define a number of critical infrastructures and technologies which are subject to screening. The U.S. screening mechanism features two unique characteristics. Firstly, it is very closely linked to export controls. Secondly, it encompasses a whitelist of countries for which certain easements apply.

COMMONALITIES AND DIFFERENCES

While there are considerable differences in investment screening mechanisms, there are several key elements which can be found in all of them. Firstly, most screening mechanisms include cross-sectoral, sector-specific and entity-specific approaches – to varying degrees in the different countries. Regarding specific sectors subject to review, most mechanisms apply to defence industries, critical infrastructure, information technology, data and strategic industries, as well as new and emerging technologies. Secondly, all screening mechanisms feature a trigger mechanism for screening. Triggers include, for example, (i) the value of a proposed investment (e.g. UK); (ii) sectors in which an investment is planned to be made (e.g. France, Germany, USA); (iii) the characteristics of an investment; (iv) the type of asset being acquired (e.g. USA); (v) the extent of ownership/control over the enterprise (e.g. Germany); and (vi) the share of a product/service market that would be controlled by the enterprise (e.g. Italy, UK). Thirdly, the screening mechanisms include criteria for review. Criteria mostly relate to public order and national security, but some countries go further, applying a national interest test to a planned investment (e.g. Australia, USA). Criteria are usually very broadly defined. The fourth commonality is that most mechanisms give governments the power to conditionally approve or block foreign investment. Some go as far as giving a government the power to order the divestiture of an implemented investment (e.g. Australia, Canada).

Proposals for G20 initiatives

There are four trends which can be observed in many G20 countries. Firstly, the triggers for investment screening are being lowered in many developed countries. Secondly, the criteria for screening are being broadened. Thus, new criteria are being introduced, going beyond traditional concerns. At the same time, the definitions and interpretations of what constitutes national security are changing. In some countries, social costs are taken into consideration (UNCTAD, 2019; UNCTAD, ongoing; OECD, 2020b). Thirdly, concerns regarding the type of investors, in particular state-owned enterprises, are growing. Fourthly, screening legislation usually does not identify specific countries of origin of investment as screening triggers. However, in the implementation, investment from certain countries – foremost China – is often subject to particular scrutiny. Lastly, some countries are trying to make investment screening more transparent and accountable. In general, however, considerable room for interpretation of legal terminology often remains. And data on covered and/or banned transactions is hard to come by.

Both the UNCTAD and the OECD have tried to increase transparency on investment screening by compiling information on current trends and country-specific developments. Investment screening is now also part of the G7 agenda. Furthermore, the G7 has an Investment Screening Expert Group, which discusses guidelines for investment screening. The group also serves as a forum for exchange on best practices as well as on trends, for example subsequent to the COVID-19 pandemic. At their summit in mid-June 2021, the G7 countries agreed to enhance cooperation on investment security within the Investment Screening Expert Group to ensure resilience.

The G20 countries have – so far – shied away from discussing this politically sensitive issue. This is not surprising given the conflictual nature of the topic and the divergent views on the nature and goals of investment screening even among industrial countries, and even more so between developed and emerging economies. This does not make the topic less pressing. Quite the contrary, it is high time to analyse the implications for FDI flows, for global competition and for foreign policy are analysed. And it is high time to initiate a debate among G20 leaders to develop a common understanding of the impact of FDI flows and screening on growth prospects.

In general, investment screening is a justified policy tool to protect national security and public order. However, an overly broad interpretation of these interests, inclusion of an increasing number of sectors and opaque decision-making could create new investment barriers.

The debate about investment screening is still in its infancy. We therefore propose the following recommendations:

Proposal 1: Commission international organizations to undertake a stocktaking exercise as well as comprehensive and regular reviews of investment screening

Since 2009, the G20 has mandated the OECD and the UNCTAD to publish biannual reports which monitor the commitments made by G20 countries not to introduce new barriers to trade and investment. These reports form part of wider reports on G20 trade and investment measures jointly published by the OECD, World Trade Organization (WTO) and UNCTAD. The latest report from November 2020 stresses that “COVID-19 has accelerated the introduction and strengthening of policies to counter threats to essential security interests that may be associated with foreign investment in the health sector. Overall, risk-related investment policy making has reached a historic all-time high in the first nine and a half months of 2020” (OECD, WTO and UNCTAD, 2020).

These reports form a good basis for a regular review of G20 investment screening, but they need to be much more detailed and in-depth in nature to provide the basis for a fact-based discussion in the context of the G20. Thus, the G20 should commission international organizations to conduct a comprehensive stocktaking exercise and to compile regularly updated comparative legal analyses of the different screening mechanisms. Furthermore, they should be commissioned to compile data regarding the extent and impact of investment screening, not only showing the percentage of investment potentially screened in individual countries and worldwide but also listing investments which were banned. This is necessary to evaluate the economic impact of investment screening.

Proposal 2: Commission international organizations to develop a list of best practices in investment screening

On this basis, international organizations could propose areas for G20 cooperation on investment screening, identifying best practices. What triggers (national security, national interest, etc.) are commonly used for the screening process? How can criteria be best defined to make them as concrete and not liable to interpretation as possible to avoid the politicization of decisions? Regarding the implementation of the screening mechanisms, it could be useful to include regular stakeholder consultations as well as sunset provisions (best practices regarding implementation: inter-agency set up; oversight).

Proposal 3: Initiate a debate among G20 countries on investment screening by establishing a Working Group

It would be too ambitious to expect the G20 to agree on joint guidelines for investment screening in the near future – but it is necessary to draw the leaders’ attention to this sensitive topic as well as to build a basis for better understanding in order to ensure that investment screening will not become the next big barrier to foreign investment flows. As such, a step forward could be to set up an Investment Screening Expert Group, as has been done in the G7, and to put the topic on the agenda of the Finance Ministers track. The aim would be to discuss on a high political level the outcome of the stocktaking exercise as well as the proposals for best practices and, based on this, to provide regularly updated reports with basic policy recommendations for the leaders’ level.

ANNEX A1

Investment Control and Screening in G20 Emerging Economies (G20 countries with no stand-alone investment screening mechanism)

Argentina: Regarding its essential security interests, Argentina has caps on foreign ownership in the production of war weapons and ammunition, established by Ley No 12.709 (October 1941), and requires government approval for acquisitions of real estate situated in security zones under Decreto Ley 15.385 (1944). As the OECD points out, these mechanisms have not undergone structural changes since at least the 1990s, and little is known about the practical use and outcomes of decisions under these mechanisms (OECD, 2020a). Basically, Argentina has a very liberal investment regime. FDI is not subject to specific authorization, even if this leads to a majority share of a domestic company. The exceptions are sensitive sectors such as air and road transportation (maximum 49 per cent), as well as media industries (radio and television, 30 per cent cap), which are based on public interest criteria. In the oil and gas sector, Argentina has banned hydrocarbon activities in the disputed Falkland Islands. Moreover, Resolution No. 407 and Law 26,659 dated from 2007 prohibit the registration in the Registry of Petroleum Companies. Some enterprises in sensitive sectors such as defence, energy or telecom services are also kept in state ownership.

Brazil: In Brazil, Lei 6.634 (1979) and Decreto No. 85.064 of 1980 deal with acquisition and ownership risks relating to its security interests through controls over activities that are conducted within a security zone of 150 kilometres along its borders. Regardless of nationality, investors need to acquire prior approval by the National Security Council for certain investments in this area. The sectors include transfers of land, construction of certain infrastructure and means of broadcasting, and establishment and operation of certain industries. Enterprises in the border zone also need to have majority ownership by Brazilian nationals (OECD, 2020a). In general, Brazil has an investment promotion strategy in place which focuses on automobile manufacturing, renewable energy, life sciences, oil and gas, and infrastructure sectors. Foreign investors in Brazil receive national treatment. However, Brazil has investment restrictions in health, mass media, telecommunications, aerospace, rural property and the maritime sector. Foreign investors must register their investment with the Central Bank of Brazil within thirty days of the inflow. In June 2019, Brazil eliminated the 20 per cent cap for airlines. The Brazilian Congress is also considering legislation to liberalize restrictions on foreign ownership of rural property. However, the economic situation during the COVID-19 crisis has led to consideration of tighter investment screening reforms in Brazil (OECD, 2020b).

India: The Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIT), the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and the Government of India consolidated the previous Indian FDI Policy, effective from 15 October 2020. India differentiates between foreign investment, which enters through the “automatic route” in specific sectors limited to a certain investment cap, and investment, which needs to enter through “government approval”. The government route is necessary for an entity of a country which shares a border with India, while an entity of Pakistan is even further restricted through a ban on investment in certain sectors. As such, India uses the country of origin as a trigger. Further triggers are equity caps and the requirement for the government route for approval to deal with national security risks. The majority of equity caps relate to acquisitions from 49 to 100 per cent. Critical sectors in foreign investment include the defence industry, broadcasting, civil air transport services, telecom services, power exchanges and pharmaceuticals. Criteria for the screening of individual sectors relate to national security and public interest

REFERENCES

Euler Hermes (2021). The World is Moving East Fast, 18 January, https://www.eulerhermes.com/en_global/APAC/apac-economic-research/the-world-is-moving-east-fast.html

Kratz A, Huotari M, Hanemann T, Arcesati R (2020). Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 Update, 8 April, https://merics.org/en/report/chinese-fdi-europe-2019-update (accessed April 5, 2021)

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2020a). Acquisition- and ownership-related policies to safeguard essential security interests, Current and emerging trends, observed designs, and policy practice in 62 economies, May 2020: https://www.oecd.org/Investment/OECD-Acquisition-ownership-policies-security-May2020.pdf (accessed 30 March 2021)

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2020b). Investment Screening in Times of COVID – and Beyond, 23 June, https://www.oecd.org/investment/Investment-screening-in-times-of-COVID-19-and-beyond.pdf (accessed April 2021)

OECD, WTO, UNCTAD, Reports on G20 Trade and Investment Measures (Mid-May to Mid-October 2020), November 2020: https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/24th-Report-on-G20-Trade-and-Investment-Measures.pdf (accessed 22 April 2021)

UNCTAD, Global Foreign Direct Investment Fell by 42% in 2020, Outlook Remains Weak, January 24, 2021, https://unctad.org/news/global-foreign-direct-investment-fell-42-2020-outlook-remainsweak (accessed 5 April 2021)

UNCTAD, Investment Policy Monitor: Special Issue – National Security-Related Screening Mechanisms for Foreign Investment: An Analysis of Recent Policy Developments, Special Investment Policy Monitor, December 2019, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/publications/1213/investment-policy-monitor-special-issue—national-security-related-screening-mechanisms-for-foreign-investment-an-analysis-of-recent-policy-developments (accessed April 5, 2021)

UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/ (accessed April 5, 2021)