Amidst global challenges and uncertainties, low-income countries (LICs) and lower middle-income countries (LMICs) will continue borrowing and pushing debt levels to further heights, in order to alleviate social costs and to jump-start the recovery phase, which is expected to be more inclusive and green. In the absence of a comprehensive financing infrastructure framework to develop their economies, these countries will not be able to build inclusive, green economic resilience and, hence, continue the payment of the debt stock they have. In 2021, in a paper[1] for the T20 in Italy, we proposed and described an innovative public-private partnership (PPP) financing framework that decouples financial and execution risk, which relies on either domestic or international financial markets to finance infrastructure development, with guarantees from the LMICs and partial guarantees from international financial development institutions with a higher rating, to reduce the cost of financing. This framework is described as the Ready for Audit Framework (RAF), the essence of which is to monitor the performance of the executing entity by an independent reputable audit firm and to disclose progress to the investors and guarantor(s).

The proposal of this new paper is to outline the pillars of the regulatory framework (policy, tools and institutions) that would regulate a new market for financing infrastructure development with enhanced transparency, liquidity and sustainability. The domestic and international dimensions will be highlighted, introducing the two-tiered regulatory framework.

Challenge

Financing public infrastructure is essential for the growth agenda of developing countries. Due to increasing government indebtedness, particularly in lower middle-income countries (LMICs) and reducing public fiscal space, private sector investment and financing are expected to grow.

According to the World Bank (WB) data[2] and report[3], there is a large infrastructure[4] gap: “940 million individuals are without electricity, 663 million lack improved sources of drinking water, 2.4 billion lack improved sanitation facilities, 1 billion live more than 2 kilometers from an all-season road, and uncounted numbers are unable to access work and educational opportunities due to the absence or high cost of transport services”.

In LMICs, the developed infrastructure falls short of what is needed to address public health and individual welfare, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and environmental targets, as well as to achieve economic development and growth. It is worth noting that infrastructure, such as healthcare and other social facilities, is not included in the definition used by the WB.

LMICs would have to spend between 2 and 8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) per year up to 2030 on new infrastructure, depending on the quality and quantity of the targeted service and the spending efficiency. To achieve the SDGs and to comply with the 2 degrees Celsius target to curb climate change and by applying the right policies, an average investment of 4.5 percent of GDP would allow these countries to achieve a sustainable development track.

However, the report emphasises that investing in infrastructure must go hand-in-hand with maintaining it. This means additional capital expenditure for maintenance services. These maintenance services must be efficient, in order to generate substantial savings (more than 50 percent) to reduce the total life-cycle cost of transport, water and the sanitation infrastructure.

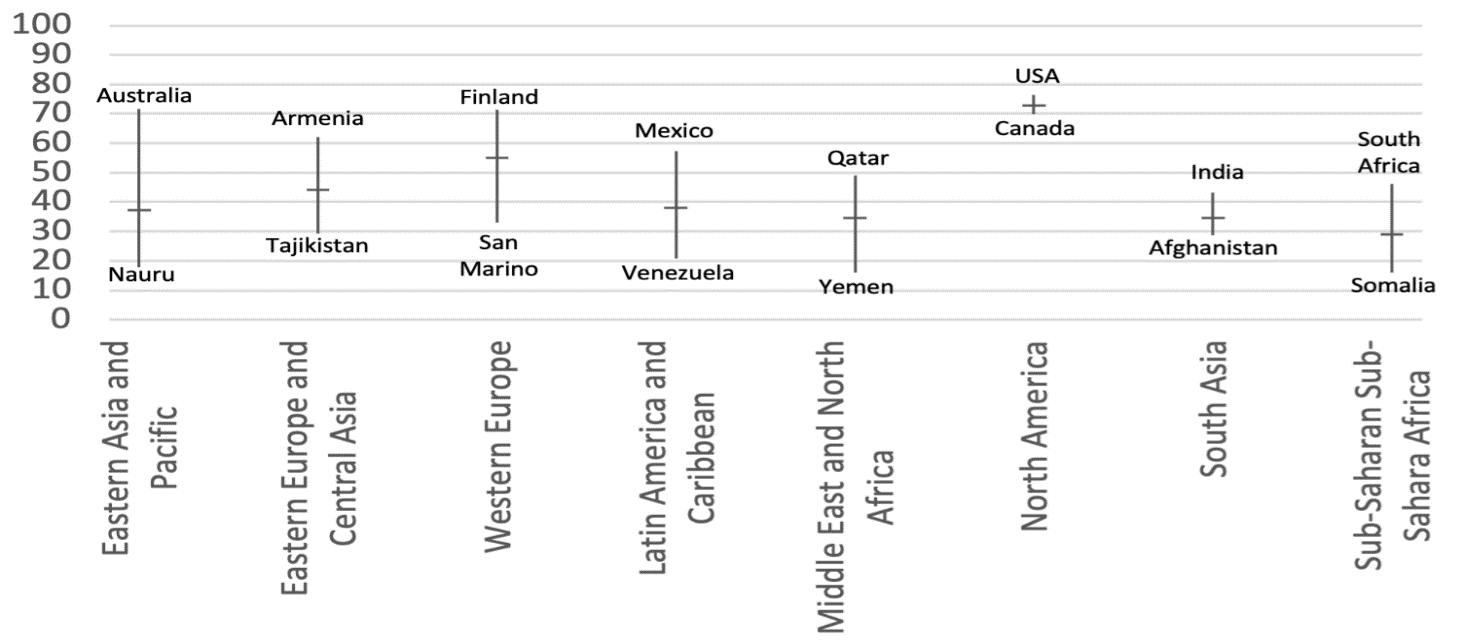

The COVID-19 pandemic showed that healthcare and other key social infrastructure are lagging behind and unprepared to deal with a heath emergency and social needs (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Global Health Security Index – regional averages

Note: The regional classification follows the one used by the Global Health Security (GHS) Index, whilst Southeast Asia in the graph includes both Southeastern Asia and Southern Asia. The GHS Index is a project of the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and was developed with the Economist Intelligence Unit. The average overall GHS Index score is 40.2 out of a possible 100. Whilst high-income countries report an average score of 51.9, the index shows that, collectively, international preparedness for epidemics and pandemics remains very weak.

Source: Author elaboration based on data retrieved from the Global Health Security Index. https://www.ghsindex.org (accessed 20 April 2022).

In their paper, Ayadi et al.[5] (2021) emphasised the urgent need to strengthen infrastructure investment and financing for green and inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in LMICs.

Regrettably, LMICs are not only fiscally constrained but the most vulnerable countries amongst them are facing default scenarios, because of increasing sovereign indebtedness and lack of capacity to honour their obligations[6]. Proposals have been put forward[7] to curb indebtedness and free-up fiscal space for infrastructure development that is SDG- and climate target-compliant, with a systematic contribution from the private sector and attracted investment.

Ayadi et al. proposed new financing mechanisms underpinned in public-private partnerships (PPPs), a carefully regulated framework as a means to attract private financing and necessary investments, in order to fill the financing gap in infrastructure development.

PPPs have been used for decades with various levels of success, due to several factors in government spending (e.g. lack of transparency, high level of corruption, poor governance, lack of accountability and weak capacity, among others).

Whilst LMICs continue to battle with the socio-economic consequences of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, exacerbating the contraction of their fiscal space, they ought to fill the financing gaps of their infrastructure development requirements. This is necessary to develop a resilient response to facing future shocks, for dealing with environmental challenges and to continue growing and paying their domestic and external debt. However, the lack of a policy and regulatory framework for new financing mechanisms, underpinned in PPPs, hampers development adding to the overall policy void and regulatory uncertainty.

Proposal

The 2008 global financial crisis and stricter regulations on banks, including higher capital requirements, not only reduced banks’ appetites to fund infrastructure projects by traditional debt, but also reduced the internal rates of return for project developers, particularly in LMICs. Since then, accessing institutional bond markets has become a viable alternative for funding infrastructure projects, via dedicated project bonds[8] that aim to reduce the cost of funding. However, because of the inherent high risk attached to infrastructure construction and related performance, the market has remained small and largely underdeveloped. The increasing sovereign indebtedness of LMICs, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, has reduced the capacity of these countries to access international funding.

As a follow up to the paper by Ayadi et al. (2021) [9] introducing the PPP financing framework, in this paper we propose a policy and regulatory framework to regulate the functioning and management of this new form of financing, whilst taking into account the key objectives – mainly enhanced transparency and liquidity and contributing to sustainable development (introducing the environmental, social and governance [ESG] assessment matrix), reinforcing stability and resilience.

PPPs are generally defined[10] as long-term contracts between a private party and a government agency for providing public assets or services, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility. PPPs are useful mechanisms for risk sharing between the private and public sectors; they are service oriented, efficient and bring in expertise in infrastructure development projects (IDPs).

Ayadi et al. propose a PPP financing framework in the form of a market financing i.e. PPP bonds that decouple country and execution/performance risks.

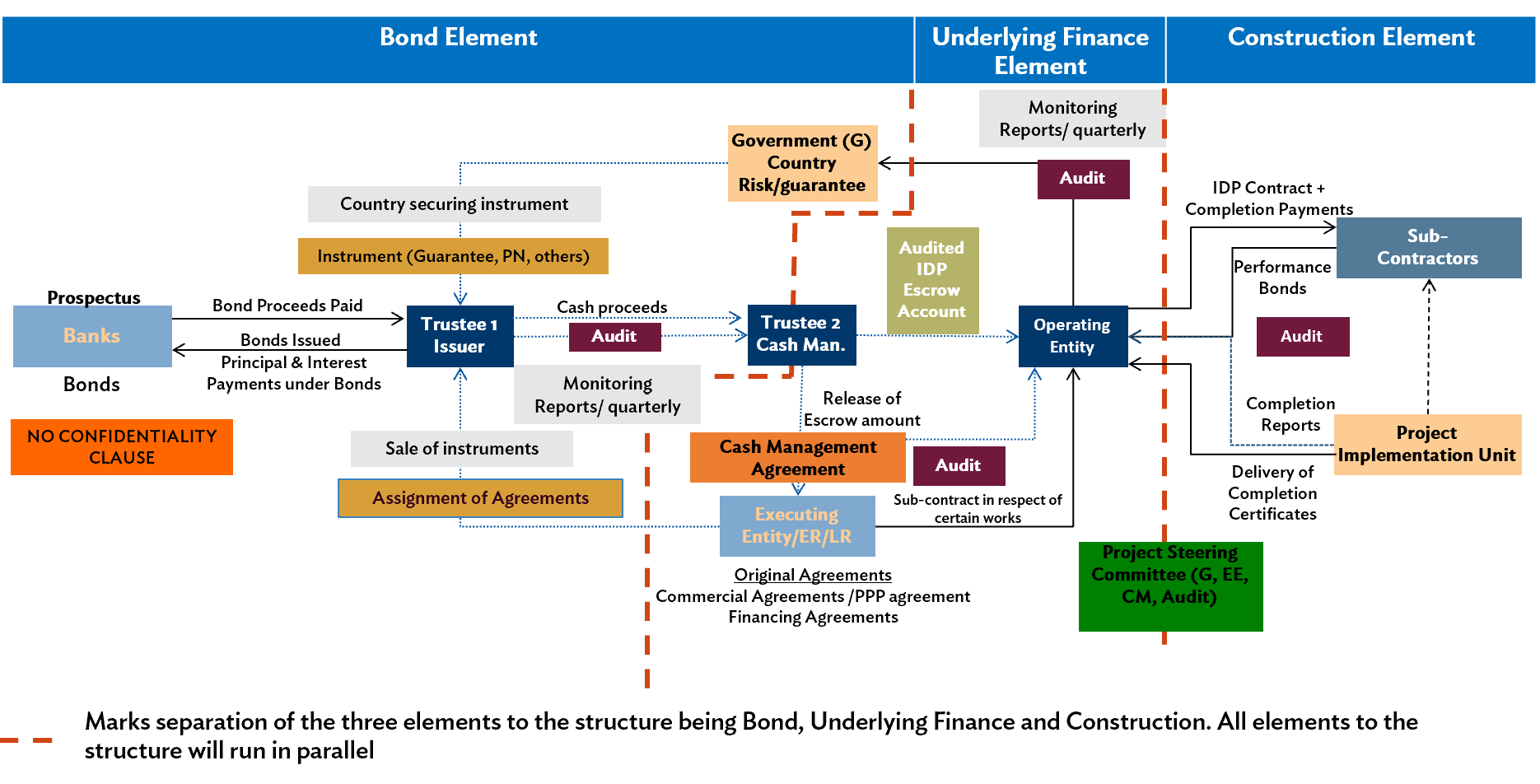

The bond structure relies on the financial pillar. The stakeholders include the following:

- Government institutions: to guarantee the debt for IDPs and to pay for country risk

- Promoters/developers: to develop the IDPs and assume and manage execution risk

- Financing institutions: financial institutions, advisors and investment funds: to structure the financing and invest in country risk against a pre-defined fee

- Corporate advisors, legal and trustees: to set-up the special purpose vehicles (SPVs) and legal agreements

- Audit firms: to perform independent due diligence assessment (including value for money of the proposals by the developers) and monitoring of use of funds

The financial pillar is built on underlying government assets (e.g., guarantees from governments and co-guarantees from international development institutions) to pay for the cost of the project and/or the cash flow that it could generate. The government that guarantees the debt (which can be domestic or external) must go through a debt sustainability assessment[11] performed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to ensure that the country has the financial capacity to pay back its debt with the relevant maturity. In situations of major external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or any other similar events, other assessments may need to be performed to ensure the debt guarantor can honour its financial obligations under strict conditions. When the bond is structured with the underlying guarantee of the governments that will benefit from the IDPs, the trustee, responsible for the issuing SPV, will hold the financial exposure and must be reputable, independent (from the government and the developer) and have the adequate technical capacity to manage the financial risks.

The proceeds of the bond for the IDPs must be held in escrow account for the execution of the IDP and be systematically audited against approval from the trustees, who legally hold the funds under a dedicated SPV and are responsible for monitoring the use of funds. The underlying financial instruments (such as guarantees or other financial instruments) must be custodied by international banks that will manage the clearing and settlement of the payments. Preferably, the trustee responsible for the SPV that issued the bond for the IDP, should receive regular reports on the execution risk from the trustee who is responsible for the SPV that disburses the funds under a strict framework, pre-agreed during the fund-raising phase.

The underlying debt, in whichever form, must be disclosed in a globally recognised registry, as argued in Ayadi and Avgouleas[12] (2020), and the issuer must be fully independent from the government and the developer.

The execution pillar includes the following stakeholders:

- Construction companies and developers: to take and manage execution risk

- Audit and management firms: to monitor the execution risk and the use of funds

- Finance institutions: to custody the project accounts and instruments

- Governments institutions: to monitor the implementation of work

- Corporate advisors, trustees: to manage the implementation of agreements and use of funds

The execution/performance risks are externalised from the bond structure and are the responsibility of the project’s developers and associated construction companies.

When the bond is issued and proceeds are raised for a specific project and escrowed in a project account for the benefit of the project, under a dedicated SPV, the funds will be subjected to strict regulation (e.g., fund management agreement) and monitored via a reputable independent audit firm that will be required, under the prospectus of the bond, to periodically disclose the progress of the projects to the trustees responsible of the issuance, investors and the co-guarantors.

In case of non-performance of the executor, following at least two consecutive quarterly meetings with the appointed officials responsible for monitoring project progress on behalf of the government and the auditors, predetermined prompt corrective action is implemented. In case of performance, the executor will be paid a portion of the margin in deferred consideration.

This financing structure is viable only if the following requirements are fulfilled:

- The underwritten debt is approved by the relevant country authorities, is transparent/officially registered in official international repository and pari-passu and cross-acceleration with euro bonds

- The promoter/developer/ construction company has technical, legal and financial capacity (part of due diligence assessment) and margins are not-front loaded

- The IDP costs pass through value for money (VfM) assessment, with margins publicly disclosed

- The role of the independent audit and management firm is stressed from the start of the process

- Prompt corrective action in the case of material risk in execution phase is assessed independently by the auditor:

i) To reduce corruption, execution and reputational risk

ii) To reduce sovereign risk (i.e., lower incentives to default, lower probability of default and higher recovery rate)

iii) To reduce risk premiums – in lower yields and higher price of bond

There is also a role for digital technologies:

- To increase management efficiency of complex PPP infrastructure projects

- To monitor the quality of infrastructure and execution of maintenance contracts via dedicated software

- To streamline dialogue and consultations between stakeholders: aimed at reducing corruption, execution and reputational risk, to reduce sovereign risk (i.e., lower incentives to default – lower probability of default and higher recovery rate) and to reduce risk premiums – in lower yields and higher price of bond

The framework could rely on a mix of finance (due diligence and risk assessment), ESG assessment to comply with the SDGs and commercial and international public procurement by the relevant regulatory institutions, in order to manage the financial and execution risks of the financing infrastructure projects, aimed ultimately at enhancing performance and overall governance.

The key pillar of the regulatory framework is the Ready for Audit which, in essence, is to monitor the performance of the execution by a relevant regulatory agency during the life of the project. On the financing, the financing entities such as banks and investment firms, must abide by full transparency using a public registry of the debt underwritten by the relevant country. A previous paper [13] explained the importance and role of the debt public registry.

This financing structure (Figure 2) has the following benefits:1) it enhances predictability for the investors and reduces the reputational risks; 2) it reduces the corruption and operational risks; and 3) it increases the certainty of execution.

![]()

Source: Author elaboration

Conclusion

LIMCs are in dire need of developing their countries’ infrastructure, to sustain green and inclusive growth and to pay back their external debt. International efforts to progress debt relief and restructuring, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, are putting pressure on the financial standing of these countries and are reducing the opportunities for them to access private sector funding. The Group of 20 (G20) could support a global policy and regulatory framework for PPP infrastructure financing, in close cooperation with international organisations (e.g., WB, IMG, OECD) and the private sector, represented by the Institute of International Finance (IIF). This framework could complement the debt transparency initiative led by the OECD.[14]

References

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/sustainable-and-quality-infrastructure-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic-proposals-for-new-financing-models/ ↑

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2019/02/19/data-table-infrastructure-investment-needs-in-low-and-middle-income-countries ↑

- https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31291 ↑

- Infrastructure —defined as water and sanitation, electricity, transport, irrigation, and flood protection— ↑

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/sustainable-and-quality-infrastructure-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic-proposals-for-new-financing-models/ ↑

- From May 2020 to December 2021, the initiative suspended $12.9 billion in debt-service payments https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/covid-19-debt-service-suspension-initiative ↑

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/debt-relief-for-sustainable-recovery-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-proposal-for-new-funding-mechanisms-to-complement-the-dssi/ ↑

- In a project bond, the issuer raises funds to finance a single indivisible large-scale capital investment project, whose cash flows are the sole source to meet financial obligations and to provide returns to investors. In the case of a typical corporate borrower, the security is issued against the firm’s general credit and the underlying assets consist of multiple sources of cash flows. ↑

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/sustainable-and-quality-infrastructure-beyond-the-covid-19-pandemic-proposals-for-new-financing-models/ ↑

- https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/about-us/about-public-private-partnerships ↑

- https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/ ↑

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/time-to-implement-a-tech-driven-sovereign-debt-transparency-initiative-concept-design-and-policy-actions/ ↑

- https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/time-to-implement-a-tech-driven-sovereign-debt-transparency-initiative-concept-design-and-policy-actions/ ↑

- The author is a member of the Advisory Board of the OECD debt transparency initiative https://www.oecd.org/finance/debt-transparency/#:~:text=The%20OECD%20has%20launched%20the,data%20from%20low%2Dincome%20countries. ↑