In increasingly multi-ethnic societies, discrimination of immigrants is a challenge for social cohesion. A large-scale conjoint experiment we conducted in Germany shows that native citizens reward immigrants who (A) have high educational attainments or (B) actively engage in community work, with (B) triggering higher rewards than (A). We then recommend the establishment of volunteering partnerships where immigrants join local civil society associations and perform community work. We recommend the strengthening of active labour market policies for immigrants, the involvement of the media sector in disseminating unbiased information to the public, and actions to increase social interactions between natives and immigrants.

Challenge

Migration is one of the most serious challenges for societies around the world.

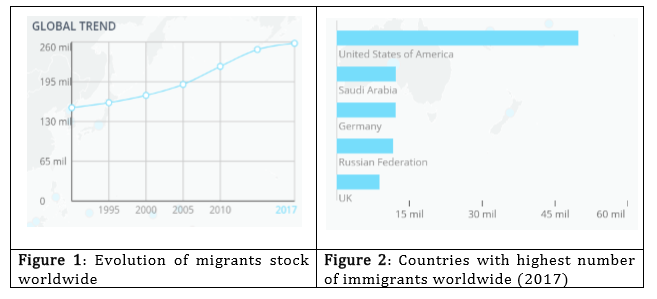

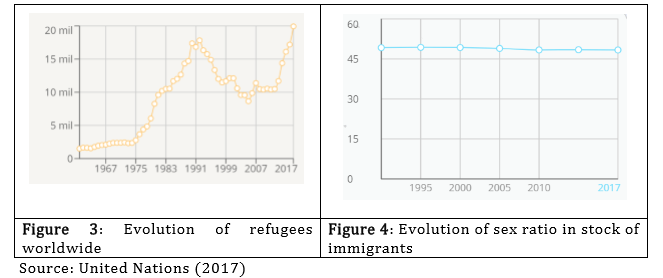

- According to the United Nations (2017), the stock of internationalimmigrants1 in 2017 was 258 million people, equal to 3.4% of the world population (See Figure 1).

- Migration is on the rise (See Figure 1). With demographic growth in Africa and Asia, demand for emigration towards richest countries is expected to further increase in the next decades.

- Countries receiving the largest number of immigrants are part of the G20 (see Figure 2). The US is the country receiving the largest number of immigrants- with nearly 50 million foreigners living in the US in 2017. Saudi Arabia is the second most preferred country by emigrants, with about 12 million foreigners.

- Only a minor proportion of immigrants are refugees – about 8%. However, their number is fast increasing (see Figure 3).

- The migrant stock is nearly equally balanced across gender, with only a slight majority of male migrant (51.6% of the total in 2017; see Figure 4

Migration is relevant under many domains, such as global income redistribution (Milanovic, 2016) and brain drain (Docquier & Rapoport2012). In this policy brief we focus on social cohesion

Studies on immigrants’ integration tell a completely different story depending on the level of analysis.

- At the micro or psychological level, the available evidence (almost exclusively coming from North-Western countries) suggests that integration may be successfully achieved. Social psychologists have put forward two contrasting theories regarding the impact of being exposed to racial or ethnic diversity. Contact theory (Stouffer, 1949; Allport, 1954) states that encounters of natives and immigrants reduces social distance, so with time discrimination will decrease (Blumer, 1958; Blalock, 1967). Conflict theory argues instead that people become even more radicalized after different ethnicities mix. The available evidence, reviewed in a meta-study by Pettigrew and Tropp (2006), suggests that contact theory prevails over conflict theory.

- At the meso-or sociological level- comprehensive evidence shows instead negative effects for ethnic and racial heterogeneity in urban districts or countries on various macroeconomic outcomes. Heterogeneity reduces trust in others (Alesina & La Ferrara 2002), propensity to join associations (Alesina & La Ferrara 2000) – thus negatively affecting social cohesion (Easterly et al., 2006). Ethnic heterogeneity also reduces public goods spending in US metropolitan areas (Alesina et al., 1999), propensity to redistribute (Luttmer, 2001), and economic growth (Easterly and Levine, 1997). We believe that the main reason for the mismatch between micro-level and meso-level evidence is that integration of different racial or ethnic groups has not yet been satisfactorily achieved. This policy brief aims to tackle the issue of how to improve integration in multi-ethnic societies.

Proposal

The psychological basis of discrimination and the vicious circle between discrimination and lack of integration

- As argued by Adida et al. (2010), discrimination and lack of integration are two sides of a vicious cycle. They observe how the French white majority tend to discriminate against immigrants because of their reluctance to integrate in French society. This attitude is particularly strong against Muslim immigrants, who indeed show persistent attachment to the values of their ancestors’ motherland even after two or three generations of establishment in the country (Basin et al., 2008). On the other hand, immigrants do not want to integrate because they feel discriminated against. A virtuous circle is instead one where natives do not discriminate against immigrants, who then find optimal conditions to integrate.

- Why is there discrimination in the first place? One of the dominant theories in social psychology is so-called social identity theory (see Box 1 in the Appendix). A key insight from the empirical investigations related with this theory is that individuals have a natural tendency to categorize others into an “ingroup” – the group with whom the individual identifies– and the “outgroup” – a group with whom the individual does not identify (Brewer, 1999).Extensive empirical evidence shows that most individuals will tend to favor the ingroup over the outgroup and to discriminate against the outgroup (Balliet et al., 2014).

- Why is this the case? Arguably the reason rests in human evolution. Our psychology has been shaped in situations of strong inter-group competition over scarce resources, such as food. According to one theory, the psychological propensity to cooperate – a typical human trait – rests on the need to help people from one’s own group in a conflictual situation with competing groups (Choi and Bowles, 2007). It is then not coincidental that human brain assesses whether another person belongs to one’s ethnic group even faster than the capacity to assess gender or age.

- This tendency to categorize others into ingroups and outgroups is “natural”, in the sense that it is embedded into basic human psychological traits inherited from our evolutionary past. However, this does not mean that this tendency is irreversible, especially in our era where evolutionary pressures are scarce, if not inexistent. Extensive research shows that many people acquire so called “cosmopolitan” personalities, where the cleavage between ingroups and outgroups is removed (Buchan et al., 2009). Globalization should further strengthen the spread of cosmopolitan values. As argued by Giddens (1991: 27), “with globalization humankind becomes a we, where there are no others”.

- Moreover, theorists distinguish between two types of discrimination. Taste-based discrimination is associated with generally negative judgement of the outgroup that is invariant to additional information over the outgroup. Statistical discrimination is instead based on negative beliefs over the outgroups – for instance beliefs that the immigrants would be lacking work ethic, or holding too different values from those held by natives, or being undeserving of help because they have not contributed to society’s wealth in the past or because they are prone to committing criminal offences (Gilens, 1999). Such beliefs are often factually wrong and lead to stereotyping. Statistical discrimination offers greater leverage to reduce discrimination than taste-based discrimination. Spreading correct information over immigrants may rectify factually wrong beliefs and thus reduce statistical discrimination. How to unlock the vicious circle between discrimination and lack of integration?

- We believe that effective mechanisms to break the vicious circle illustrated above should build on the two aspects illustrated in the previous section that are most conducive to decrease discrimination: (a) Remove stereotypes over immigrants; (b)Desegregate and increase contact between people from different groups;

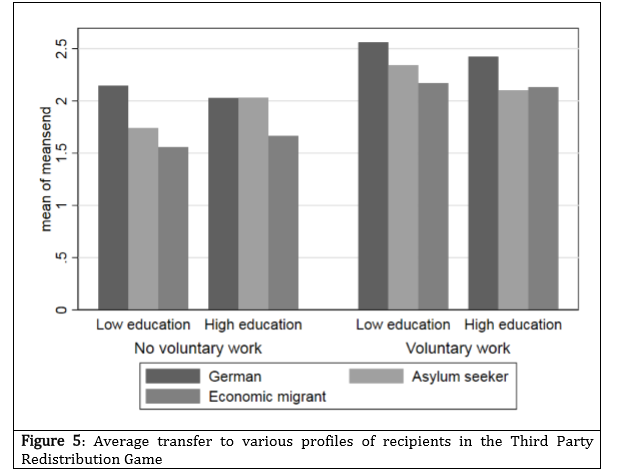

- With respect to (a), we conducted a large-scale internet experiment investigating whether releasing information that immigrants are active contributors to communities helps reduce natives’ discrimination. Participants were involved in a simple experimental game, which we call the Third-Party Redistribution Game (TPRG). This is a decision framework well-established in experimental economics to infer social preferences (Almås, 2010). Box 2 in the Appendix describes he TPRG. The key variables for our analysis are the transfer of money that the participant implemented from a German citizen towards an immigrant recipient. As typical of conjoint experiments, different profiles were given for the recipient’s characteristics. Profiles differed according to some attributes that we deemed as important in affecting discrimination.

- The attributes we considered were:

- (A) Citizenship status, where status can either be being an asylum seeker or an economic immigrant.

- (B) Engagement with community, where engagement can be either not performing or performing community work;

- (C) Educational attainment, where this can either be Educational attainment equivalent to secondary school or university degree.

- Attributes (B) and (C) were also assigned to German recipients. The comparison of the transfers sent to German recipient Vs. an immigrant permits us to quantify the extent of discrimination and how this is affected by the various attributes.

- Discrimination is widespread. For all possible profiles, German recipients receive higher or equal transfers than immigrants; Only for one immigrant profile – low-education asylum-seeker performing community work – is the discrimination gap annulled; overall, immigrants receive transfers that are 14% smaller than those received by German recipients. The amount of discrimination seems therefore substantial.

- Economic immigrants are more discriminated against than asylum seekers. Transfers towards asylum-seekers are about 11% smaller than those to Germans, while those to economic immigrants are17% smaller. A reasonable interpretation is that economic immigrants are more discriminated against than asylum seekers, because the latter are considered as more deserving and more needy than the former. This idea is also often stated in the political debate.

- Both performing community work and having university degree increase propensity to redistribute towards immigrants. Performing community work denotes an immigrant’s willingness to actively engage in the community and to deliver a positive benefit to the collectivity. As expected, German citizens reward this behavior with higher transfers in our experiment. High educational attainment also increased reward. High education denotes both high potentials to contribute to the community and commendable “moral” qualities. In fact, many countries attribute preferential visa to high-skilled workers (see Implementation Overview in the Appendix).

- It is worth noting that even if transfers to immigrants increase considerably, discrimination decreases less than proportionally, or even stays constant, because transfers to a German recipient also increase by an amount similar to the increase for an immigrant(with the above mentioned exception of the situation in which an asylum-seeker has high education and does not perform community work, for which discrimination is annulled). Therefore, the higher propensity to transfer to immigrants should be framed in a context in which German citizens are generally seen as deserving preferential treatment over immigrants.

- Performing community work permits larger increases in transfers towards immigrants than having university degree. This result is surprising inasmuch as skilled immigrants have higher potential to benefit host countries than performing community work. Nevertheless, our results clearly indicate that participants in our experiments rewarded community workers more than highly skilled immigrants. This result offers great scope for policy. While it is relatively easy to facilitate community work for immigrants, favoring the attainment of a university degree may be difficult if not impossible.

- It is also evident from our analysis that the two attributes –performing community work and having university degree – do not reinforce each other in increasing transfers. Achieving high educational attainments in addition to carrying out community work does not increase transfers. This might suggest that the “returns to scale” of expanding the number of attributes that receive favorable treatment may be limited. Our recommendations: Community work appears as a powerful tool to increase acceptance of immigrants

Recommendation 1: Establish community work programmes involving both immigrants and local voluntary associations. Such programmes should have a voluntary basis and should be oriented towards activities that have clear beneficial effects for the community. Examples are assisting the poor and the sick, cleaning up litter in the park, invigilating areas that are at risk of crime, or assisting people in need.

- Such type of activities would have many advantages in addition to public goods provision:

- They would permit “transmission” of the relevant social norms from natives to migrants, let alone language skills.

- They would contribute to remove natives’ prejudices associated with immigrants’ poor work ethic, or their unwillingness to integrate into the native community.

- They would show to the native population immigrants ‘willingness to contribute to community life. Since good intentions may matter more than final outcomes, the action of helping the community without receiving any tangible return may be important to remove negative stereotypes among large portions of the native population.

- Community work would also contribute to remove immigrants’ prejudice that they are discriminated against. Since voluntary association and pro-social spirits are not in short supply in many communities, the opportunities for immigrants’ involvement may be abundant.

- Our proposal shares some similarities with Atkinson (2015)’advocacy of the state acting as an employer of last resort in activities that have public utility. As such, the involvement in such activities should not be compulsory but accessible on a voluntary basis by both immigrants and associations. Public authorities should nonetheless play a role in encouraging immigrants ‘participation explaining their benefits. Native citizens’ participation as volunteers should also be encouraged. Associations may receive subsidies to implement these activities. The existence of such activities and their beneficial consequences should be disseminated across citizens.

Recommendation 2: Establish active labor market qualification programmes for immigrants. Even if rewards of community worker are higher than rewards to people holding a university degree in our experiment, the latter also has a positive impact. This evidence suggests that active labor market policies that increase immigrants’ professional skills should be pursued. The benefits may be particularly high for asylum-seekers. Clearly, native citizens may question that the costs of such programmes are worthwhile. Studies on active labor market policies show that not all programmes may be equally effective. In particular, wage subsidies for employers who hire disadvantaged workers seem to ensure the highest returns (Kluve, 2010; Butschek and Walter,2014). It then becomes important to choose the most appropriate programme of active labor market policy. Moreover, it is important to consider the whole range of benefits that integration in the labor market brings about, such benefits often extend beyond the purely economic sphere. A recent study conducted in Denmark shows that the negative effects of reducing welfare benefits for immigrants include increased property crime, reduction in household incomes, withdrawal of female immigrants from the labor market, immigrants’ children worsening of language skills because of increased school dropout rate (Andersen et al., 2019).

Recommendation 3: Policies should strive to be characterized by impartiality, and care should be taken that natives are seen to benefit as much as immigrants from the policy programmes that are implemented. We already noticed that a striking result stemming from our study is that, even if the propensity to reward immigrants significantly increases with the attributes object of our study, the reward of natives also increases proportionally. Our statistical analysis confirms that discrimination is overall reduced for individuals possessing the favorable attributes object of our study, that is, holding a university degree and performing community work. Nonetheless, participants in our study generally saw natives as deserving more than immigrants. We are aware that people’s attitudes and opinions are often not objective, being led by stereotypes, unfounded beliefs, and being easily manipulable by “political entrepreneurs” fostering divisive political discourses (Glaeser, 2005). For these reasons, governments should take particular care in their communication strategies with communities and with the citizenry, spelling out the benefits for both natives and immigrants of the programmes to be implemented. Dialogue with citizens and with relevant stakeholders is necessary at various stages. Before the implementation stage it is necessary to engage the public into dialogue to gain consensus over the programme. After the implementation stage, it is also necessary to monitor the results of the programme and to disseminate the results of such monitoring.

Recommendation 4: The media sector and relevant civil society organisations should be involved in the process of transmitting to the public information that is unbiased and free from stereotyping of immigrants. This goal should be realized without denting the independence of the media sector. By relevant civil society organisations we mean organisations that are active in factchecking activities with reference to fake news. We recommend that the government encourage media agents to elaborate, take up and disseminate codes of conduct aiming to ensure unbiased communication of news, restrain from stereotyping of immigrants, and willingness to communicate “success stories” of immigrants’ integration in society rather than focusing exclusively on negative stories of failures to integrate.

Recommendation 5: Policies to reduce segregation at the urban or social level should be put in place. Even if this was not a goal of our study, the evidence we mentioned in the challenge section reveals positive psychological predisposition in reducing discrimination and treating more favorably people of different ethnicity. Therefore, in accordance with “contact theory”, governments should aim to increase the possibility of social contacts between natives and immigrants. This should occur at different levels. At the residential levels, policies should be put in place that reduce the residential segregation of ethnicities. The situation where different ethnicities inhabit different districts of a city should be avoided, either with subsidizing the payment of housing rents or through programmes of public housing. Mixing people from different ethnic background in schools should also be favored. Cultural exchanges and the organisation of multi-cultural events should also be encouraged. As forcefully argued by Putnam (2007), the long-run benefits of mixing people from different groups – be their religious, ethnic, or economic – far exceed the short-term costs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Mercator Dialogue on Asylum and Migration (MEDAM), to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy Research Initiative for funding the experimental project on which the recommendations of this policy brief are based. We also thank Fondazione Franceschi ONLUS for providing a scholarship to one of our research assistants.

References:

- Adida, C. L., Laitin, D. D., & Valfort, M. A. (2010). Identifying barriers to Muslim integration in France. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(52), 22384-22390.

- Alesina, A., La Ferrara, E. (2000). Participation in heterogeneous communities. Quarterly Journal of Economics, August, 847–904.

- Alesina, A., La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trust others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207-234.

- Alesina, A., R. Baqir, and W. Easterly (1999) “Public goods and ethnic divisions”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114 (4): 1243-1284.

- Allport, G. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Almås, Ingvild, Alexander Cappelen, Erik Sørensen and Bertil Tungodden (2010). ‘Fairness and the development of inequality acceptance’, Science 328(5982), 1176-1178.

- Andersen, L. H., Dustmann, C., & Landersø, R. (2019). Lowering Welfare Benefits: Intended and Unintended Consequences for Migrants and their Families (No. 1905). Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), Department of Economics, University College London.

- Atkinson, A. B. 2015. Inequality –What Can be Done?. Harvard University Press.

- Balliet, D., Wu, J., & De Dreu, C. K. (2014). Ingroup favoritism in cooperation: a metaanalysis. Psychological bulletin, 140(6), 1556.

- Bisin A, Patacchini E, Verdier TA, Zenou Y (2008) Are Muslim immigrants different in terms of cultural integration? J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2-3):445–456

- Blalock, H. M. Jr. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-group Relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 3–7.

- Blumer, H. 1958. ‘Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position’, Pacific Sociological Review 1,

- Brewer, M. 1999. ‘The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love or Outgroup Hate’, Journal of Social Issues 55, 429–44.

- Buchan N, Grimalda G, Wilson R, Brewer M, Fatas E, Foddy M, (2009). “Globalization and Human Cooperation”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 106 (11): 4138-4142.

- Butschek, S., & Walter, T. (2014). What active labour market programmes work for immigrants in Europe? A meta-analysis of the evaluation literature. IZA Journal of Migration, 3(1), 48.

- Choi, J., Bowles, S. (2007) The coevolution of parochial altruism and war. Science 318: 636-640.

- Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. 2012. “Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development”. Journal of Economic Literature, 50/3: 681–730.

- Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. The quarterly journal of economics, 112(4), 1203-1250.

- Easterly, W., Ritzen, J., & Woolcock, M. (2006). Social cohesion, institutions, and growth. Economics & Politics, 18(2), 103-120.

- Fong, Christina, Samuel Bowles, and Herbert Gintis, (2005). “Strong Reciprocity and the Welfare State.” in: Herbert Gintis, Samuel Bowles, Robert Boyd, and Ernst Fehr (eds). Moral Sentiments and Material Interests: The Foundations of Cooperation in Economic Life, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Giddens, Anthony. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gilens, M. (1999), Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Anti-Poverty Policy, Chicago University Press.

- Glaeser, E (2005). The Political Economy of Hatred, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120 (1), 45-86.

- Grimalda G, Tänzer N, (2018). Understanding and fostering social cohesion. G20 Insights. T20 Task Force on Global Inequality and Social Cohesion.

- Kluve, J. (2010). The effectiveness of European active labor market programs. Labour economics, 17(6), 904-918.

- Louis, W. R. Duck, J. M. Terry, D. J. Schuller, R. A. Lalonde, R. N., (2007). “Why do citizens want to keep refugees out? Threats, fairness and hostile norms in the treatment of asylum seekers” European Journal of Social Psychology 37, 53–73.

- Luttmer, E. F. 2001. “Group Loyalty and the Taste for Redistribution”. Journal of political Economy, 109/3: 500–528.

- Milanovic, B. 2016. “Global Inequality: a New Approach for the Age of Globalization”. The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- OECD (2018). International Migration Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Ottaviano, G. I., & Peri, G. (2005). Cities and cultures. Journal of Urban Economics, 58(2), 304-337.

- Ottaviano, G. I., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 152-197.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(5), 751.

- Putnam R (2007). “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century”, Scandinavian Political Studies, 30 (2), 137-174.

- Stouffer, S. 1949. American Soldier. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M., Oakes, P., Reicher, S., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2017 Revision (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/ Rev.2017).

- Zimmermann, Klaus F., Thomas K. Bauer, and Magnus Lofstrom. “Immigration policy, assimilation of immigrants and natives’ sentiments towards immigrants: evidence from 12 OECD-countries.” (2000).

Appendix:

Box 1: Social Identity Theory

- Social identity is “that part of the individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Turner et al., 1987). Social identity relies on categorization – namely, the psychological process of assigning people to categories-, identification – namely, the process whereby an individual associate him/herself with certain groups -, and comparison – i.e. the process whereby one’s own group is compared with other groups. A key distinction is put forward between the “ingroup” and the residual category of the “outgroup”. An ingroup can be defined as a group to which an individual (a) categorizes herself as being part of, (b) identifies with, and (c)triggers comparisons with other groups.

- Turner et al. (1987) proposed three possible levels of self-categorization, categorization at the level of humankind being the highest. At the intermediate level differences between one’s ingroup and outgroup and similarities within one’s ingroup help define the self, while at the lowest level it is the differentiation from other ingroup members that shapes an individual’s identity. Most of the research effort related to social identity has thus far focused on the intermediate level of ingroup-outgroup categorization, investigating the conditions under which ‘ingroup favoritism’, i.e. a tendency to treat more favorably ingroup members than outgroup members in situations of strategic interaction, is generated.

Box 2: The Third-Party Redistribution Game

- In the experimental social sciences, participants make decisions allocating sums of money, provided by the researchers, to different allocations. People are paid the sums of money corresponding to their decisions at the end of the experiment. Decisions are normally made under conditions of anonymity and are often computer-mediated, without interactions between participants. In conjoint experiments participants are asked to examine different profiles of people, or different scenarios, and are then asked to express a preference between the two.

- Our TPRG involves three participants, whom we call Person 1, Person 2 and Person 3.

- Person 2 is not assigned any money in the experiment. Person 2’s profile is modified over the different conditions of the experiment. In particular, a profile for Person 2 is obtained by varying these three dimensions:

- (A) Person 2’s citizenship status, where status is one out of three characteristics:{German citizen; asylum seeker; economic immigrant};

- (B) Engagement with community, where engagement can be one out of two characteristics: {Not performing community work; Performing community work};

- (C) Educational attainment, where this can be one out of two levels: {Educational attainment equivalent to secondary school; University degree}.

- The matching of (A), (B) and (C) determines 12 possible profiles. For instance, one of such profile for Person 2 is: “Asylum seeker not performing community work and holding a university degree”.

- Person 1 is a German citizen and is endowed with 5€ for having performed some tasks for the researchers. Person 1’s profile is invariant throughout the experiment. Person 1 receives the three attributes that are most common in the German population with respect to the three areas described above: Person 1 is thus a German citizen who does not hold a university degree and does not perform community work.

- The first two participants are real people but are not “active” agents of the game. The only active agent of the game is Person 3. Person 3 receives information over Person 1 and Person 2’s profiles. While Person 1’s profile is held constant, Person 2’s profile varies as illustrated above. Person 3’s has to decide how much money she wishes to redistribute from Person 1 to Person 2. With the help of a polling organization, we recruited a sample of 1800 German citizens born in the country to act as Person 3. The sample was nationally representative with respect to gender, age group, education (as a proxy of socioeconomic status), and geographical residency. Person 3’s choice has been actually implemented in 10% of the cases.

Implementation Overview

Migration policies differ for economic migrants and for asylum seekers. In case of economic migrants most countries are interested in the immigration of high skilled workers (Zimmermann et al., 2000). To facilitate the migration of high skilled workers, many G20countries made it easier for high skilled workers to enter the labor market and for employers to recruit them. Additionally, they introduced shortage lists for specific sectors. In case of asylum seekers countries try to streamline their procedures to improve the handling of matters concerning appeals and to speed up decision process – e.g. fast track procedures – and they tightened-up their asylum policies. They introduced measures to stop asylum seekers at borders, reduced time to submit applications for protection visa and tightened the family reunion immigration.

In response to the increasing migration, G20 countries sought to improve their immigration policies towards a better integration. They focused on the integration of migrants into the labor force, introducing programmes to promote language skills, educational attainment and acknowledgment of foreign qualification (OECD 2018).

As a response to increased migration flows and natives’ apparent resentment against immigrants, labor market policies were rolled back in recent years (Andersen et al., 2019). For instance, immigrants’ access to social assistance and public benefits was restricted in Canada, Finland, France, The Netherlands, Latvia, Lithuania, Switzerland (OECD, 2018). The Austrian government’s proposed cut in refugees’ transfers in 2017, and restrictions to immigrants’ access to welfare have also been proposed in Germany. European countries 17Social Cohesion, Global Governance and the Future of Politics approved, in the period 2000-2017, 158 bills regarding refugees’ and immigrants’ welfare eligibility, programme requirements, or welfare levels (OECD, 2018).

Existing policies for economic migrants

American green card (“Lawful Permanent Resident Card”): The green card is an identification card indicating the holder’s status to live and work in the USA permanently.

European blue card: The EU Blue Card is a work- and residence permit for non-EU/EEA nationals, which was adopted in 2009 (EU-Directive 2009/50/EG). All EU member states -except the United Kingdom, Denmark and Ireland- issue the EU Blue Card.

General Skilled Migration (GSM) Program: The program is the only path for skilled workers to emigrate to Australia. Candidates must meet the Basic Requirements for GSM and pass the Australian immigration Points Test to qualify for a visa to move to Australia. Australia and New Zealand introduced Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) Visa in 2017 replacing the Temporary Work (Skilled) Visa. The TSS visa comprises a short-term stream (valid for up to two years) and a medium-term stream (valid for up to four years for more critical skills shortages).

Existing Integration Programs

Australia

Australia introduced two new integration programs. The Community Support Program (2017) enables communities, businesses and individuals to propose humanitarian visa applicants with employment prospects and to support new arrivals. Supporters need to demonstrate their ability to provide adequate funding to enable refugees to achieve financial self-sufficiency within the first year in Australia. The Career Pathways Pilot is a three-year project to assist newly arrived humanitarian migrants to get a similar profession to the one they had in their origin countries. Pilot participants must be within the first five years of settlement, with professional or trade skills and a good English proficiency. Additionally, Australia established an Australian Multicultural Council which advises policies which help to build social cohesive communities and they set up funds to fund projects which help immigrants to participate in the society.

European Union

In 2016 the EU formulated an action plan to promote integration of migrants of third country nationals into the European countries. The primary goal of the action plan is to harmonize the integration strategies of the member states, supporting integration efforts and intensify the policy cooperation and coordination on migration and integration policy.

The plan offers exchange platforms, coordination tools and funds the policy areas of migration and integration pre-departure/pre-arrival measures, education, labor market and vocational training, access to basic services, active participation and social inclusion. Active participation and social inclusion of migrants includes funds to launch projects in the domain of sports, voluntary service and the active participation of migrants in political, social and cultural life of the host societies.

Canada

The Canadian government formulates three core responsibilities in the Canadian immigration and migration policy. This includes Visitors, International Students and temporary Workers, Immigrant and Refugee selection and integration and Citizenship and Passports. Regarding the integration of immigrants and refugees the Canadian identified the promotion of active participation of migrants in the Canadian society as a as a key to integration. It collaborates with non-governmental institutions and organization to promote voluntary service by immigrants and refugee. The target of immigrants and refugee to engage in voluntary service is at least 30% and has been exceeded in the period 2015-16.

Mexico

Mexico launched a special migration program between 2014-18 which besides structure immigration in Mexico also contained the goal to expand public space for cultural exchange between citizens and immigrants as well as funding projects to support the cultural exchange.