While only one African member is formally part of the G20, Africa remains severely underrepresented in the most important multilateral group regarding global economic and financial cooperation. This policy brief argues that a greater degree of global integration and regional representation is key to ensuring the long-term legitimacy of the G20 itself. For this to be achieved, the G20 needs to become more inclusive, particularly by systematising its relationship with African multilateral institutions. Strengthening the relationship between the G20 and African multilateral institutions could be key to ensuring that a complex and diverse continent is better represented in global decision-making bodies. It also argues that the more systematic inclusion of African multilateral institutions should be followed by changes in the way the AU itself guarantees that its participation in G20 discussions will be more effective and meaningful.

Challenge

Since the expansion of the G20 in 2008, it has become one of the most important global representatives of “club diplomacy”, replacing the major role once played by the G7 in global economic and financial cooperation (Bertoldi, Scherrer, and Stanoeva 2016; Sidiropoulos 2019). As a key grouping for international economic and financial cooperation, Africa has, unsurprisingly, featured regularly in its discussions. This type of engagement with the continent can be exemplified by the G20 Compact with Africa (CWA), launched during the German G20 presidency in 2017 to increase the engagement of the G20 with specific African countries.

South Africa is the only African member of the G20, and its membership has been important in elevating the role of Africa within the group. To some extent, South Africa could, in principle, be seen as a gateway for African voices and for improved representation, as it has worked towards ensuring that the group includes discussions relevant to African development, particularly issues dealing with illicit financial flows (IFFs) and infrastructure financing (Sidiropoulos 2019, pp. 3-4). However, South Africa’s membership, while important, is not enough to ensure an effective participation of Africa in the G20.

In most G20 summits and working group meetings, African issues have been raised in the discussions, often focusing on development cooperation arrangements with the continent. In addition, the chairs of the African Union (AU) and the African Union Development Agency-New Partnership for African Development (AUDA-NEPAD) have regularly been invited as observers to the G20 process (Bradlow 2013, p. 5; Sidiropoulos 2019, p. 27).

However, despite South African and African efforts, promoting African voices and the idea of African agency remains problematic within the G20. With only South Africa as member, Africa remains severely underrepresented in the G20 and the continent is often seen as a subject rather than an agent. Africa is mainly approached from the point of view of how G20 countries can support African development; little space is given to elevating Africa’s agency and voice in G20 decisions (Leininger 2017; Mabera 2019).

In principle, the invitation of African member states (beyond South Africa) and multilateral institutions could further promote the inclusion of African voices in the group. However, these invitations are generally based on the initiative of the G20 chair in a particular year, being conducted more on a customary and ad hoc basis, rather than as part of a more systematic engagement (Mabera 2019).

Also, the fact that invitations to African multilateral institutions are limited to the chairs of the AU and AUDA-NEPAD, who are appointed in a rotational basis, implies that most of the persons invited have little previous engagement on G20 issues (Sidiropoulos, Elizabeth, personal communication, 27 April 2021). These challenges exacerbate the limited scope for Africa to fully influence decisions in the body.

This policy brief argues that to remain relevant globally, the G20 needs to become more inclusive, particularly by systematising and formalising its relationship with African multilateral institutions. Permanent membership, preferably full membership, for Africa in the G20 would help to institutionalise the continuity of issues discussed and help monitor progress on achievements and identify emerging gaps in a systematic way. Therefore, strengthening the relationship between the G20 and African multilateral institutions would be a key mechanism for ensuring that a complex and diverse continent is better represented in global decision-making bodies. The brief also argues that to be successful, a more systematic inclusion of African multilateral institutions should be followed by decisions by the AU and AUDA-NEPAD (both at political and technical levels) on how their participation in G20 discussions can become more effective and meaningful.

Proposal

Since the transition from the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) to the African Union (AU) in 2002, Africa has been at the forefront of innovative multilateral practices. From using a wide range of tools, including the Lagos Plan of Action (1981) and more recently the development of Agenda 2063, African multilateralism has not been short of ambition.

Two recent examples showcase Africa’s ambitions. First, the transformation of NEPAD into AUDA-NEPAD is a key indicator of the continent’s commitment toward directing its own development. Second, the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCTA), is expected to boost intra-African cooperation and elevate the role of the continent within global economic chains. These developments are part of the process of ensuring that Africa’s development path is changed and triggered by increasing growth.

These examples show that African states, through the role played by the AU, are increasingly positioning themselves to advance a common voice that can enhance the continent’s leverage globally and its ability to ensure that its agency and voice are effective. The following sections discuss two proposed solutions that the G20 and AU may consider in engagements between the G20 and African multilateral institutions.

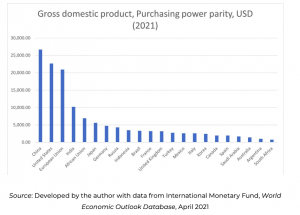

Individually, most African countries would not be even close to meeting the loose criteria set by the G20 for membership of the group of the world’s largest economies. Most African nations are among the least developed countries (LDCs). The G20, on the other hand, is dominated by the greatest global economic powers, as well as a range of middle-income emerging countries.

However, if seen as a collective, Africa accounts for 17% of the global population, and 4% of the world economy (Cilliers 2021). By 2040, according to the forecast produced by Jakkie Cilliers, Africa is expected to represent 28% of the world’s population, though still only around 4% of the global economy (2021, p. 15). While this percentage may seem small at first sight, when compared to other members of the group, the AU membership as a whole would actually counts as the fifth largest economy within the G20, in front of countries like Japan, Germany, or Russia.

Fig. 1 Gross Domestic product among G20 countries and the AU

The G20 is a key symbol of why multilateralism matters for countries, as it provides them with a platform to find solutions and identify mechanisms that can reduce economic insecurity and foster trust and cooperation. For African states, multilateralism matters even more:

“By pooling resources and ideas, and searching for common approaches, multilateralism can be advantageous to smaller players, largely benefitting them by setting out the rules of the game, to which all states have to adhere (De Carvalho, Mutangadura, and Gruzd 2019, p. 6).”

Therefore, by sitting at the margins of G20 decisions, Africa misses the opportunity to advocate for positions that are not only beneficial to the continent, but also increase the global integration, regional representation, and legitimacy of the G20 itself.

The G20 already includes the European Union (EU) as one of its full members, alongside France, Germany, Italy, and Spain (a permanent guest invitee), and from time-to-time other European members observe discussions. Certainly, the EU has some supranational capacities that the AU lacks, including regulatory functions and binding power over members (e.g., development of monetary policies). However, its mere presence as a full member illustrates the fact that the G20 already acknowledges the importance of including regional voices in its decision-making processes.

Studies have shown that the presence of the EU at the G20 level can be mutually beneficial and that both institutions add to each other’s agenda and action, including at the EU commission level (Bertoldi, Scherrer, and Stanoeva 2016). Inclusion of the AU and AUDA-NEDAP chairs should therefore be extended to the AU Commission and AUDA-NEPAD bureaucracy. Ensuring that the senior leadership and technical personnel of the AU Commission and AU-NEPAD are better represented, particularly in the working group levels, could provide an opportunity not only to get their voices heard, but also to generate an incentive loop that enables African member states to implement decisions made by the group.

Considering the AU is busy implementing the AfCTA, a more systematic inclusion of the AU in G20 decision making processes can be a great opportunity for more seamless global economic governance. While trade is not a major area of discussion in the G20 (Sidiropoulos, Elizabeth, personal communication, 27 April 2021), when fully implemented, the AfCTA will become one of the largest drivers of growth in the continent. The free trade area provides a major opportunity for increased complementarity amongst African economies, leading to more sustainable development and growth.

The G20 can benefit by ensuring that its recommendations are relevant and applicable beyond the context of advanced economies and key middle-income powers. This does not mean that doing so would be a simple process. But to increase G20 legitimacy and ensure that Africa is not disadvantaged by G20 decisions, the continent’s active presence is key.

Therefore, the G20 should further promote cooperation and collaboration with African multilateral institutions, and the AU and AUDA-NEPAD, by institutionalising, formalising and even expanding its engagements with these institutions, their political leaders, and their bureaucracies. This should be done first by systematising engagement with the AU and AUDA-NEPAD, and potentially formalising their inclusion, either as permanent observers, like Spain, or potentially as full members, like the EU.

ADJUSTING THE AU’S APPROACH TOWARDS MORE MEANINGFUL ENGAGEMENT WITH THE G20

Through its multilateral institutions, Africa has, in the last decades, attempted to increase its voice and position in the world. This has often been done by promoting common views and standpoints that not only guide the continent’s collective views, but also enhance its leverage and its ability to contribute to global outcomes that are beneficial to the continent (Adeoye 2020). Certainly the process of identifying common African positions is far from perfect, but efforts towards further consultation, coordination and communication (Adeoye 2020, p. 2) have increased in recent years and should be taken into account.

There are many success stories of how common African positions have influenced global political outcomes, even in areas covered by the G20. The adoption of a common continental position was key in driving negotiations during the Post-2015 development agenda, which eventually led to the Sustainable Development Goals (De Carvalho, Mutangadura, and Gruzd 2019). Furthermore, the development of the African Consensus and Position on Development Effectiveness, on the margins of the 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation and the G20 Summit in Cannes, played an important role in ensuring that African development should not be achieved through development aid alone, but be driven by direct investments as a tool for development (Adeoye 2020; Rampa, Bilal, and Sidiropoulos 2012).

While the AU and AUDA-NEPAD chairs are frequently present in G20 discussions, their participation tends to be generally ineffective. Considering that their position is rotational, most AU and AUDA-NEPAD chairs have limited or no experience in engaging with the G20 in a more systematic manner. An exception, of course, was South Africa in 2020, as the country also served as the AU chair and is already a permanent G20 member.

Considering the importance of African participation, the continent needs to make sure it provides meaningful contributions to G20 decisions and discussions. Becoming more involved in G20 discussions would certainly provide benefits to the continent, but Africa also needs to change the way in which it engages in these meetings. Both the AU and AUDA-NEPAD need to identify how their institutions can provide the time and resources required for effective participation.

In the process of ensuring strong African representation, there are several issues that can be addressed at AU level to strengthen its role in the G20, preferably on a more permanent and less customary basis. These include, for instance, generating a cascade of structures that facilitate timely information gathering and sharing.

At the political level, the EU experience in the G20 indicates that AU Commissioners should be part of many working groups, especially those organised at ministerial level. Their roles could complement those of the AU and AUDA-NEPAD chairs by providing continuous engagement, especially within working groups that tend to have a more political participation.

Also, AU Member States should ensure that the positions presented by South Africa, and by the chairs of AU and AUDA-NEPAD, are based on previously defined common positions. These should ideally be decided during negotiations prior to and during the annual AU Summit in January-February but also during the mid-year coordination meetings between the AU and Africa’s regional economic communities (RECs). These common positions should ideally be included in the official communique by the AU’s Executive Committee. In this way, the AU would be able not only to verify the positions of its own member states, but make those positions more representative of how the different African sub-regional organisations see the benefit of greater engagement with the G20.

At a technical level, the AU Commission has a key role to play in assisting the AU and AUDA-NEPAD chairs by providing continuity, assistance in drafting positions, technical support, and institutional history. Creating an interdepartmental working group within the AU Commission to address G20 matters, would be a great step forward in ensuring that the organisation’s voice is better understood, clarified, and ultimately included in G20 outcome documents. Such a working group should be formed by technical staff from different departments of the AU, including infrastructure and energy; social affairs; trade and industry; rural economy and agriculture; human resources, science, and technology; and economic affairs. By establishing a dedicated team within its own structure, through the above-mentioned interdepartmental working group, the AU Commission and AUDA-NEPAD bureaucracies can effectively fulfil the role of informal support secretariat for African leadership participation in the G20. This could be a similar role to that which the AU Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations (AUPOM) fulfils as informal secretariat for the three African Member States in the UN Security Council.

Staff of the AU Commission and AUDA-NEPAD bureaucracy could also be active members of other technical working groups. Plus, the potential impact on the continent would be tangible. For instance, having more African voices in working groups like Agriculture, Health or Education would help ensure that the rules set in these discussions are not disadvantageous to Africa, considering that many of its societies are particularly vulnerable in these areas (Sidiropoulos, Elizabeth, personal communication, 27 April 2021).

Expertise already existing on the continent can be further utilised by the AU and AUDA-NEPAD. Technical support should also be provided at the T20 level, a group of G20 think tanks that provide policy recommendations and advice to G20 members. An African standing group was established during the T20 Summit in Berlin, in 2017 (Sidiropoulos, Elizabeth, personal communication, 27 April 2021). The network is a readily available source of expertise and knowledge from over 30 leading think tanks across Africa. These should be able to provide briefings, recommendations, support and expertise to the AU and AUDA-NEPAD chairs, to the AU Commission, and to South Africa in bringing key African voices to the table.

Therefore, bringing African expertise and the AU Commission and AUDA-NEPAD bureaucracy closer to the G20 organs, and particularly into its working groups, could not only produce benefits in terms of the direction taken by political decision-makers, but also provide a great opportunity to bring in unique experiences, expertise, and viewpoints from the continent to assist cooperation and ensure more effective and inclusive coordination.

CONCLUSION

A more systematic and formalised inclusion of the AU and other multilateral institutions in G20 discussions can facilitate debate on development cooperation that is not about Africa, but with Africa. The continent has its own development trajectory, encapsulated by Agenda 2063, and its experiences, concerns and suggestions can greatly benefit the G20 by making it less prescriptive in how it deals with Africa, and more inclusive in its discussions.

Despite many challenges in developing sustainable multilateral organisations, African multilateralism still plays a key role in responding to challenges that no other entity is willing or able to address. It would benefit the G20 to ensure that some of these lessons are captured, discussed, and internalised in its objectives, to enhance a broader understanding, not only of the challenges that exist on the continent, but also of the tools that are currently used to address them. It would also help ensure the G20’s long-term legitimacy though stronger representation from Africa.

If the North-South divide is to be proactively resolved, a more inclusive approach is necessary at G20 level. If Africa is only seen as a subject and not as an agent, the relationship between the G20 and the continent will remain unidirectional, imbalanced, and incomplete.

REFERENCES

Bankole A., Common African Positions on Global Issues. Achievements and Realities, Institute for Security Stiudies (ISS), December 2020 https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/ar-30-2.pdf

Bertoldi M., H. Scherrer, and G. Stanoeva, The G20 and the EU: A Win-Win Game, European Economic Briefs 009, April 2016 https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/g20-and-eu-win-wingame_en

Bradlow D., The G20 and Africa: A Critical Assessment, South African Institute for International Affairs Occasional Papers Series 145, 2013

Cilliers J., The Future of Africa: Challenges and Opportunities, Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021 https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-46590-2#about

De Carvalho G., C. Mutangadura, and S. Gruzd, At the Table or on the Menu? Afri ca’s Agency and the Global Order, Institute for Security Studies (ISS), ISS Africa Report, vol. 2019, no. 18, 31 October 2019, pp. 1-15 https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/EJC-1d23bf29c5

Leininger J., “‘On the Table or at the Table?’ G20 and Its Cooperation with Africa”, Global Summitry, vol. 3, no. 2, 2017, pp. 193-205

Mabera F., “Africa and the G20: A Relational View of African Agency in Global Governance”, South African Journal of International Affairs, vol. 26, no. 4, 2019, pp. 583-99 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10220461.2019.1702091

Rampa F., S. Bilal, and E. Sidiropoulos, “Leveraging South-South Cooperation for Africa’s Development”, South African Journal of International Affairs, vol. 19, no. 2, 2012, pp. 247-69

Sidiropoulos E., South Africa’s Changing Role in Global Development Structures: Being in Them but Not Always of Them, Discussion Paper 4, German Development Institute (D I E), 2019 https://www.die-gdi.de/en/discussion-paper/article/south-africas-changing-role-in-global-development-structures-being-in-them-but-not-always-of-them/