Over the last two decades, the world has seen a proliferation of digital platforms and the emergence of an ecosystem of digital work. Now, with the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, not only is technological change accelerating, but it is providing additional impetus for firms and workers to move work online. This geographically untethered work is creating new opportunities for homebased platform work for women that has the potential to reduce the gaps in male and female labour force participation toward significant economic gains. Yet this will only happen if policymakers enable women to adjust to, engage with, and thrive in this digital world of work punctuated by the pandemic. Such a policy and regulatory agenda entails overcoming the digital divide; addressing women’s time poverty; ensuring that homebased platform work is visible and that the online world of work doesn’t replicate or amplify offline biases; instituting labour and welfare protections that cover homebased platform workers; creating frameworks for non-judicial redressal of grievances; and promoting digital entrepreneurship that is viable and sustainable.

Challenge

Over the last two decades, the world has seen a proliferation of digital platforms and the emergence of an ecosystem of digital work. The onset of the pandemic is accelerating this trend fuelling an expansion of e-commerce and other forms of geographically untethered gig-work that can be performed from home. Many believe that these emerging forms of homebased digital work will enhance female labour force participation and narrow existing gaps in male and female participation (Appendix 1). This reduction in the participation gap, scholars believe, offers large economic benefits (Ostry, J. et al. 2018).

Whether it is driven by choice or by compulsion in the face of restrictive social norms, women often prefer to work from home (Berg et al. 2018; Sharma and Kunduri 2015; Betcherman 2017). Home-based platform work also offers greater flexibility enabling women to balance domestic responsibilities and income generation (Hewlett and Luce 2005). Given these facts, many believe that women will naturally gravitate toward homebased platform work. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this form of work is growing (Berg et al. 2018).

Yet, this form of work will only translate into meaningful economic gains if policy frameworks address the challenges that prevent women from participating in homebased platform work effectively; in a way that realises their potential. This brief addresses the question: How can policymakers enable women to adjust to, engage with, and thrive in the rapidly emerging digital world of work punctuated by the pandemic? The brief hones in on home-based platform work, assessing the challenges and opportunities it poses for women. A growing body of literature examines female labour force participation and emerging forms of work in the platform economy, but a disaggregated analysis of home-based platform work, the opportunities and challenges it poses for women and their empowerment, is still lacking.

The current reality is that not only is there a sizeable digital divide between women and men in some G20 countries in access to technology, education, and skills, but evidence suggests that the online world of work may replicate, and even intensify, existing offline biases (Athreya, 2021). Investigations into crowd work on freelancing platforms show some ways in which gender-based discrimination can be reconfigured, rather than erased, when work moves online. A significant share of women’s economic activity, such as unpaid care work, is already invisible and their contributions therefore get lost in economic accounting. Unless policymakers undertake a clear agenda to change this, homebased platform work will only exacerbate this phenomenon. Moreover, women entrepreneurs that shifted their businesses online or started new ones during the pandemic need a policy environment that is conducive to the growth and sustainability of their businesses.

Without addressing these challenges and removing the structural and systemic barriers that women confront, they will not be in a position to effectively leverage emerging opportunities in the platform economy. And policymakers will not be able to improve women’s labour market participation, or effectively harness their productive potential, to the detriment of their respective economies.

Proposal

The pandemic is accelerating technological change and providing additional incentives for both firms and workers to move work online. Homebased platform work is especially relevant in a COVID-era economic landscape, given that both public health guidelines and consumer behaviour are leading to more physical distancing and remote work. The longer the pandemic lasts, the more entrenched and lasting these trends are likely to be.

These forms of work include e-commerce platforms such as Amazon or Etsy that enable homebased artisans to connect with buyers around the globe. Social media platforms like WhatsApp, YouTube, and Facebook are providing channels for micro-retailers to find customers through their networks. Platforms, such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, or Upwork, offer women the potential to earn money while working from home, performing tasks like data entry and editing or “micro-tasks” like tagging photos or posting comments. Various food delivery platforms are also enabling women to turn their home kitchens into catering kitchens.

Leveraging the emerging opportunities in the platform economy to improve the labour market participation of women and to effectively harness their productive potential entails creating polices and regulations that are conducive to these goals. To this end, the G20 policy makers should undertake the following agenda.

OVERCOME THE DIGITAL DIVIDE BY ENABLING BETTER ACCESS TO TECHNOLOGY, EDUCATION, AND SKILLS

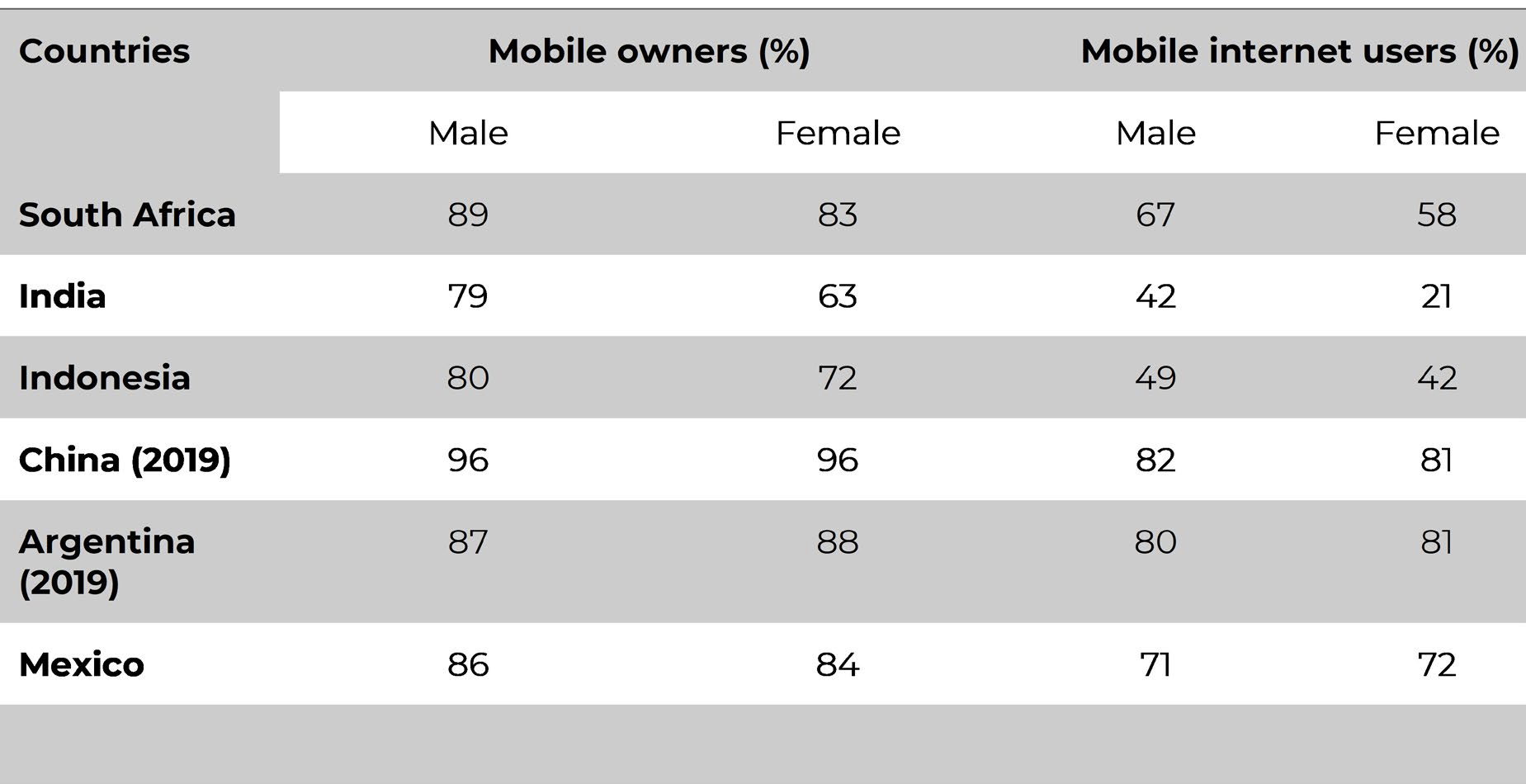

Inequity in access to technology, education and skills on the basis of gender (Appendix 2) much of which are deeply rooted in patriarchy and gender norms must be addressed to enable women’s engagement with the emerging ecosystem of digital work (Brussevich, M. et al. 2018). A recent study by the ILO highlights that not only has there been a rise in the share of workers whose work is mediated through a technology platform, but that worldwide, four out of ten workers on online web-based platforms are women (ILO 2021). The discrepancy can partly be attributed to the inequitable access females have relative to men.

Research shows that even programs that provide free or low-cost technology don’t always work because social norms in many cultures restrict women’s access to hardware and internet access (Wamala 2019). Against this backdrop, the importance of long-term public campaigns that promote girls/women’s engagement with technology at the community level cannot be overstated.

In addition to this, policymakers should pay special attention to ensuring that schools, institutions for higher education and training institutions not only foster the skills needed to participate in a technologically driven world, but that they also design programs that prioritise equitable exposure, access, and use of technology for girls. If girls are unable to acquire this access and skills on their own at home, they should be given priority in the learning institutions they are already enrolled in. This alone will not be enough to enable women to avail opportunities offered by homebased platform work, but it is a step in the right direction, removing a key barrier in terms of access to necessary education and skills.

The G20 should work with relevant multilateral organisations to provide guidance on education and skills training curricula, outlining what is appropriate at which stage of age and learning. Reformed education and skills agendas should not only focus on imparting knowledge on how to acquire and use technology digital skills, but also on cultivating a broader set of capabilities on how to productively engage with an increasingly technologically driven world that is fundamentally restructuring the way we live and work.

ADDRESS TIME POVERTY

The advantages of working from home and the flexibility that homebased digital work offers can only be realised if women are in a position to avail them. With a disproportionate burden of domestic responsibilities falling to women in many countries (Salin et al. 2018), it is difficult for them to effectively engage in income generation even if the potential to do so is greater from home. With women’s care burdens rising as children stay home from school, husbands and other members of the household work from home and additional attention is needed to protect the elderly from the virus, the pandemic has exacerbated women’s time poverty posing a real prospect of worsening the already poor control women have over their own time.

If policymakers are to leverage the platform economy to enhance labour force participation of women, as soon as the pandemic abates, they must ensure that they institute measures to alleviate time poverty. The first step to this is understanding how women spend their time through systematic time use surveys (Budlender, 2010). Second, governments should invest in the early childcare sector to facilitate access to childcare services and thus alleviate the childcare burden that typically concerns women more than men.

ENSURE THAT HOMEBASED DIGITAL WORK IS VISIBLE AND ACCOUNTED FOR

A great deal of literature documents the invisibility of women’s work (Budlender 2010). From unpaid care work to women’s participation in fragmented value chains, the extent of women’s work and economic contributions remains uncaptured by data (Barrientos 2019). Homebased digital work runs the same risk. Unless policymakers take explicit measures to make women’s homebased digital work visible, not only will women’s economic contributions continue to be discounted, but women will also remain beyond the purview of labour protections and welfare benefits. This stymies both their economic participation and productivity.

The first step to rectifying this is to promote data sharing of anonymised user data (service consumers and providers) with government officials to make women’s economic participation and their contributions visible. A recent OECD study identified two legal bases for voluntary and collaborative approaches: i) the contractual basis, and ii) data sharing partnerships, including PPPs. Governments may also want to specify what is considered “data of public interest” and render their publication mandatory, by the private and the public sector alike (OECD 2019). As data makes the scale and magnitude of women’s contributions apparent, policymakers will have additional impetus to reform labour protections and welfare to extend coverage to homebased workers with special regard to the specific needs of women.

ENSURE THAT THE EMERGING ECOSYSTEM OF ONLINE WORK DOESN’T REPLICATE OFFLINE BIASES

Recent experience with artificial intelligence has shed light on the imperfections of algorithms that reflect biases prevalent in the big data that algorithms rely on. Amazon.com Inc., for example, realised that their machine learning based recruitment tool was biased against women. The algorithm “learned from” resumes from the last ten years for certain jobs such as software developer; but previous applicants for these positions were mostly men reflecting a gender bias in the technology industry. Looking at the CVs submitted, the algorithm sorted candidates such that men over women were put forward as the preferred candidates for such jobs (Reuters 2018).

Moreover, Galperin, Cruces and Greppi (2017) also find evidence of gender-based wage discrimination on Nubelo, a freelance labour platform for the Spanish-speaking world. The G20 should institute norms for transparency and best practices in algorithm governance to avoid such discrimination that is even harder to trace in the online world than it is offline.

INSTITUTE, IN AN ITERATIVE WAY, GOVERNMENT PROVISION OF BASIC WELFARE BENEFITS TO ALL WORKERS INCLUDING HOMEBASED DIGITAL WORKERS

In the world of digital work, especially homebased digital work, the traditional employeeemployer relationship is replaced by a trilateral relationship between the service provider, the service consumer, and the technology intermediary. Moreover, a once full-time job becomes fragmented into short-term gigs. A single service provider could be performing tasks for multiple consumers. Against this backdrop, traditional models of social protection that are tied to a single employer and job break down. Who then is responsible for ensuring that these workers are protected and that they have appropriate benefits, particularly if they are homebased? Research also shows that a majority of self-employed workers, especially women of developing countries (Ranson et al. 2006) but also in OECD countries (Kwapisz 2020), do not buy insurance in the private market; many simply cannot afford it.

As these new employment relationships emerge and the world of work changes, social protection systems and the enforcement of labour protections must change as well. It should be an indisputable aspiration for all governments to provide coverage to all workers including self-employed workers; but this would not be realistic for many countries given the fiscal constraints they face, especially after the pandemic.

Against the backdrop of these fiscal constraints that confront many governments, hybrid models funded through increased tax collection, contributory models, and an iterative approach to gradually extending benefits starting with the most vulnerable income bands to others in a progressive manner is warranted. Technology intermediaries through different regimes for e-commerce platforms versus gig-work platforms, and the end consumer of the service, should both be appropriately taxed to contribute to public provision of basic welfare benefits. This calls for an examination of how these platforms are taxed and for a standardisation of tax norms across countries.

The G20 in collaboration with the International Labour Organization should agree to a framework on how to institute social protection systems and labour protections in this changing landscape of digital work, ensuring that women in homebased work are covered.

CREATE A FRAMEWORK FOR REDRESSAL FOR GIG-WORKERS

The question about how to institute enforcement and redressal mechanisms for homebased gig workers that may be located in a different country and legal jurisdiction from the buyers of that service is similar to the discussion that was raised in the context of protecting workers in global value chains. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises prompted the creation of National Contact Points for workers in different countries to seek non-judicial handling of their grievances. Although the success of this model has been limited, the G20 could build on this to explore more effective mechanisms to allow for cross border mediation and redressal for gig-workers, including homebased gig-workers.

PROMOTE DIGITAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP FOR WOMEN THE RIGHT WAY

An ongoing research project led by the authors of this brief and funded by the International Development Research Center (IDRC, n.d.), on the opportunities, costs and outcomes of the gig economy for women, indicates that women engaging in homebased platform work fall into one of two categories. They are either contractors, or entrepreneurs. Both contractors and entrepreneurs are self-employed, but entrepreneurs own and control their own means of production, the product, pricing and sales; whereas contractors often bid for tasks and are generally subject to several terms and conditions set by the technology intermediary and whomever they are performing the task for.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, with lockdowns and persistent social distancing norms that led to a decline in aggregate demand and in business for physical retailers, e-commerce emerged as a viable alternative for some small business owners. Among them were women creative entrepreneurs.

Often home-based, some women skilled in crafts, design and other creative endeavours were able to leverage their creativity, talent and intellectual property to avail opportunities brought about by the growing demand for products sold online. They fulfilled the need for products ranging from masks and other wearables to household and packaged food items. The geographically untethered nature of this kind of e-commerce enables women entrepreneurs to balance income generation with domestic responsibilities in a way that geographically tethered work may not allow (Dewan, 2021).

Success in e-commerce also ultimately relies on relatively low prices, but high volumes of production that call for larger set-ups. To enable more women to grow their businesses, they need (a) access to more and better education that includes training on how to run a business; (b) more equitable access to a steady stream of capital beyond short-term micro loans that frequently get used for consumption as opposed to business investments; and (c) more gender-specific provisions in government schemes supporting small and medium enterprises.

Finally, enabling women to capitalise on the opportunities that e-commerce has to offer entails protecting the rights of sellers (to set prices, for example) and consumers (in receipt of transparent information on issues like returns to modes of payment and delivery), but also in streamlining regulations to make e-commerce and exports more viable by reducing other compliance burdens for e-tailers. Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba in 2016 suggested that over time, the line between online and offline retail will become increasingly blurred. Regulations then need to adapt to such emerging trends and leverage the potential that e-commerce offers while ensuring checks that protect sellers and consumers.

APPENDIX

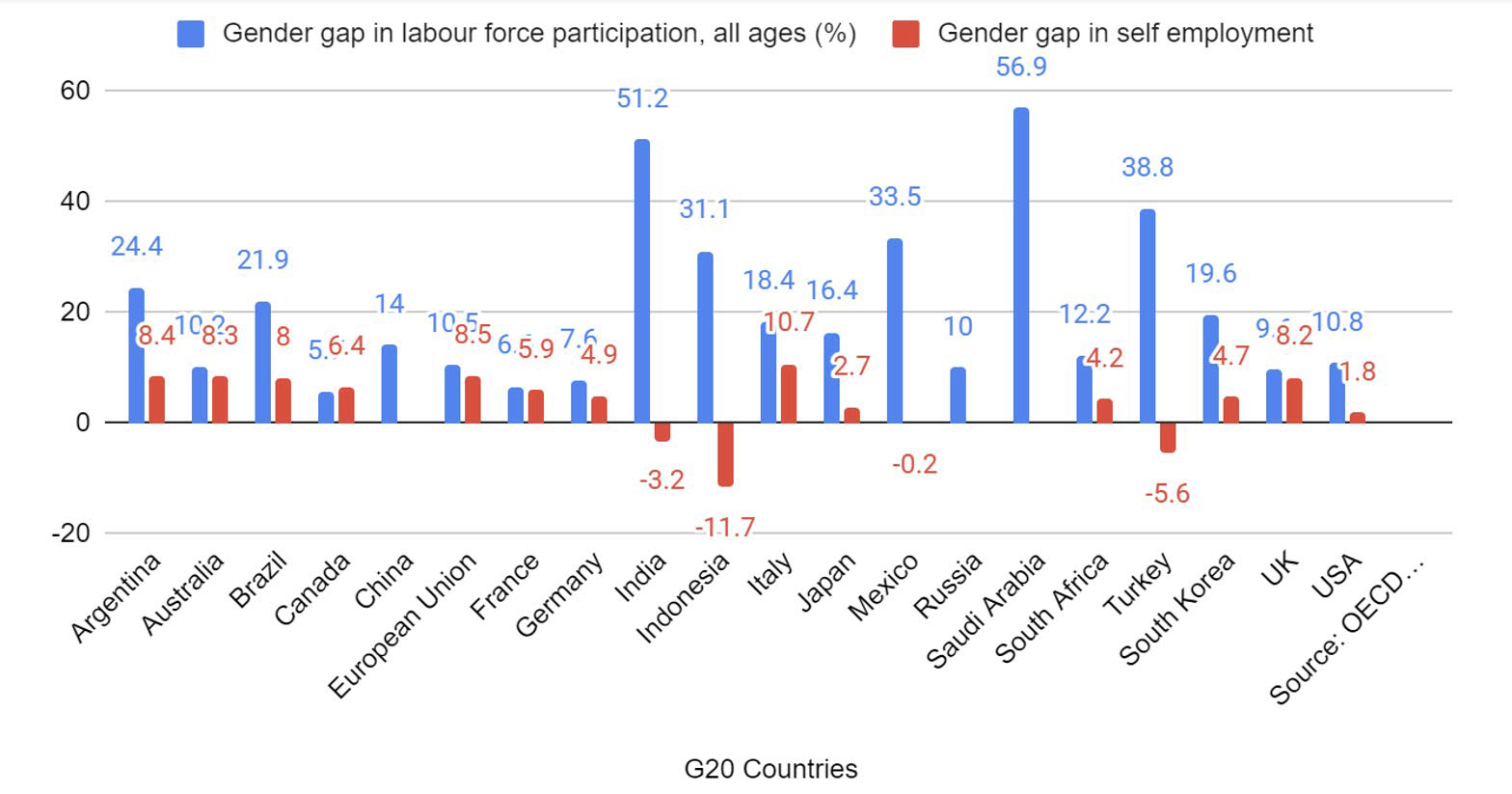

GENDER GAP IN LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION AND SELF EMPLOYMENT

Source: OECD 2017; Labour force participation Data for 2016, except from Brazil (2015), Indonesia (2013), India (2012) and China (2010); Self employment Data for 2017, except from Korea (2016), Brazil (2015), Argentina (2014) and India (2012), https://www.cippec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ GSx-GEE-Policy-Brief-Labour-participation-22.5-FINAL-1.pdf

APPENDIX 2

MOBILE OWNERSHIP AND MOBILE INTERNET USE DISAGGREGATED BY GENDER IN SELECT G20 COUNTRIES

REFERENCES

Athreya, B. (forthcoming) Bias In, Bias Out? Gender and Work in the Platform Economy, Canada, IDRC, 2021

Barrientos, S. “Frontmatter”, in Gender and Work in Global Value Chains: Capturing the Gains? (Development Trajectories in Global Value Chains, pp. I-VI), Cambridge, CUP, 2019

Berg, J., M. Furrer, E. Harmon, U. Rani, and M. Silberman. Digital labour platforms and the future of work: Towards decent work in the online world., Geneva, ILO, 2018

Betcherman, G. and I. Haque. “Employment of Women in the Greater Mekong Subregion: New Insights from the Gallup-ILO World Poll”. In Vathana Roth (ed), Job Prospects for Youth, Low-skilled and Women Workers in the Greater Mekong Subregion, Cambodia, CDRI, IDRC, 2019

Brussevich, E.D., C. Kamunge; P. Karnane,

S. Khalid; and K. Kochhar. Gender, Technology and the Future of Work., Washington DC, IMF, 2018

Budlender, D. (ed), Time use studies and unpaid care work, Routledge, 2010

Dewan, S. “Women Entrepreneurship and the E-Commerce Opportunity”, in The New Indian Express, Hyderabad, May 2021

Galperin, H. and Cruces, Guillermo and Greppi, Catrihel, Gender Interactions in Wage Bargaining: Evidence from an Online Field Experiment, 20 September 2017 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3056508.

Hewlett, S. and C. Luce, “Off-Ramps and On-Ramps: Keeping Talented Women on the Road to Success”, Harvard Business Review, vol. 83, no. 3, 2015

IDRC, Opportunities, costs and outcomes of platformized home-based work for women: Case studies of Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand https://www.idrc. ca/en/project/opportunities-costs-and-outcomes-platformized-home-based-work-women-case-studies-cambodia

ILO, World Employment and Social Out look: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work, Geneva, ILO, 2021

OECD, Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-use Across Societies, OECD Publishing, 2019

Kwapisz, A. “Health insurance coverage and sources of advice in entrepreneur ship: Gender differences”, Journal of Business Venturing Insights, vol. 14, 2020, e00177

Ostry, J.D., J. Alvarez; R. Espinoza; and C. Papageorgiou. Economic Gains from Gender Inclusion: New Mechanisms, New Evidence., Washington DC, IMF, 2018

Ranson, M.K., et al. “Making health insurance work for the poor: learning from the Self-Employed Women’s Association’s (SEWA) community-based health insurance scheme in India”, Social science and medicine, vol. 62, no. 3, 2006, pp. 707-720

Salin, M., M. Ylikännö, and M. Hakovirta, “How to divide paid work and unpaid care between parents? Comparison of attitudes in 22 Western countries”, Social Sciences, vol. 7, no. 10, 2018, p. 188

Sharma, S. and E. Kunduri, “Working from home is better than going out to the factories’: Spatial embeddedness, agency and labour-market decisions of women in the city of Delhi”, In South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, Association pour la recherche sur l’Asie du Sud (ARAS), 2019

Wamala, C. Empowering women through ICT. Universitetsservice US-AB, 2012