If ever the G20, the self-styled apex forum for international economic cooperation, needed to step up to the plate it is now. However, while it did so for the 2009 London Summit — in the eye of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) — it is highly unlikely to this time. It is also not clear what the definition of success is, unlike the GFC when the core objective was to save Western financial systems from collapse. Each G20 country is correctly focused on managing its own health trajectory, with little policy bandwidth left to devote to international economic cooperation. This has generally entailed export bans on supplies of essential health-related goods, as well as severe interruptions to cross-border value chains occasioned by quarantining requirements, negatively affecting goods and services trade. Furthermore, the growing geopolitical rift between China and the West, particularly the United States (US), had already fractured fragile trade cooperation prior to COVID-19. Now international tensions over how to manage the crisis, who is to blame, as well as who should take credit for successful disaster management amplify previous fractures. Yet when the immediate crisis abates every country will rely on a resumption of global trade cooperation to reflate economic growth, as quickly as possible. This means that the breakdown of international trade cooperation we are now seeing has to be attenuated, while at the same time allowing for the primacy of domestic health considerations. Calls for free trade to be restored are not likely to find fertile terrain amongst governments increasingly desperate to insulate their populations from COVID-19’s ravages. In that light this briefing reviews recommendations for salvaging international trade cooperation, particularly those directed to G20 leaders, applying a political economy perspective across a longer time horizon. Since the current health crisis feeds into, and greatly amplifies, the prior disintegrative forces set in motion by a number of causes [1] the analysis is embedded in a broader view of the prospects for the G20 to restore international trade cooperation. It concludes by offering a framework to guide international trade cooperation beyond the COVID-19 crisis, anchored in the military notion of ‘dual-use technologies’, and with a view to containing the worst protectionist impulses the crisis is feeding.

[1] For a dissection of these forces in relation to countervailing integrative forces, see Draper, P 2019 ‘How should Africans respond to the investment, technology, security, and trade wars?’ Africa in Focus, Brookings Institution, at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2019/09/30/how-should-africans-respond-to-the-investment-technology-security-and-trade-wars/

Challenge

Breakdown of Global Trade Cooperation

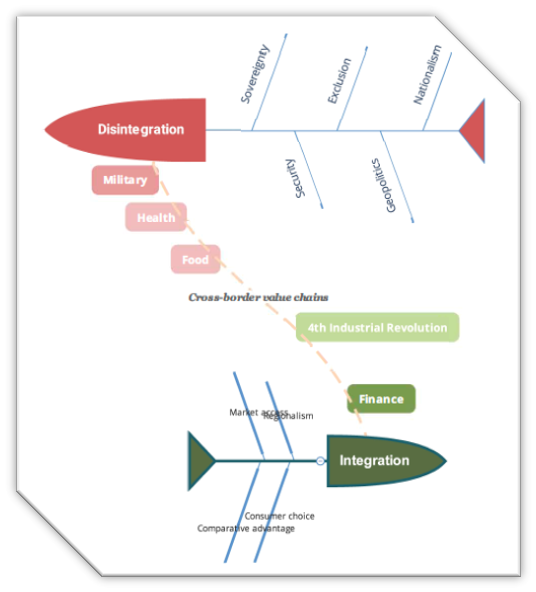

International trade cooperation has been under growing strains since at least the turn of the twenty first century. Figure 1 sets out a stylised framework for understanding this global disintegration/integration dynamic.

Figure 1: Centrifugal vs Centripetal Forces Shaping Global Trade Cooperation

Source: Author’s construction

Each primary force has a number of distinct drivers, indicated in the spines feeding into them. The thin dash line connecting the two primary, opposing, forces of integration and disintegration represents the countless cross-border value chains connecting disparate parts of the world to each other in tangible (goods, particularly parts and components) as well as intangible (services, particularly data-fuelled) terms. To each side of this divide, a number of additional core trade-related drivers are shown, each with its own dynamics. Above the central text in this divider line my assumption is that these additional drivers are currently weighted towards the disintegrative force; below the opposite is true; but in both cases the closer they are to the primary force the greater the alignment to that force. Using this framework I discuss how the current picture is evolving below, starting with a brief historical perspective on international trade cooperation over the last two decades.

Prior to the GFC market-led integration, backed by a confident US military and economic super-power, dominated international economic cooperation. It was driven by the logic of economic integration through ‘Global Value Chains’ (GVCs), led by apex firms or multinational corporations (MNCs), scouring the world in search of markets (‘consumer choice’ in Figure 1), choosing optimum production locations based on ‘comparative advantage’ (Figure 1). This was anchored in a proliferation of regional economic integration arrangements (‘Regionalism’ in Figure 1) mushrooming across the world, underpinned by the launch of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994. The lead-in to the GFC was the apex of the neoliberal ‘Washington consensus’ culminating, in the trade world, in the launch of the Doha Development Round under the WTO’s auspices.

Prior to the round’s effective collapse in July 2008[1] serious underlying tensions had become apparent across some old and new fault lines[2], notably:

- In what ways developing countries at various stages of development and with varying levels of trade integration ambition could be accommodated in the Round’s final package, or the ‘Special and Differential Treatment’ (SDT) issue

- Whether some developed countries could reform old pockets of resistance — notably agriculture (‘Food’ in Figure 1), perhaps best thought of as ‘SDT of a special type’[3]

- How new issues of interest to developed countries, notably services[4] could be meaningfully accommodated

- Would the traditional post-war engine of international trade liberalization under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) — the so-called ‘quad’ of the US, Canada, the European Union (EU), and Japan — be able to direct proceedings as they had up to that point (‘Geopolitics’ in Figure 1).[5]

The effective cessation of WTO negotiations prior to the onset of the GFC[6] signalled that business would not be as usual, and that a power shift was well underway. In a prior report I co-edited[7] we drew on political science literature to label this ‘The Interregnum’ (‘Geopolitics’ in Figure 1), referring to a period when an embedded political-economic regime is breaking down but no replacement regime yet exists to take its place. While tensions in the US-China relationship were pivotal to this power shift, there was more in play than this critical bilateral axis. Economic growth in the developing world generally continued to outpace developed world rates, and investment as well as trade flows were increasingly being directed to or from an emerging group of developing countries. These dynamics were best captured in two influential Goldman Sachs reports, on the BRICs[8], and the Next-11[9], respectively, in which the investment bank mapped out the contours of future economic growth and consumption, anchored in the emerging giants Brazil, Russia, India, and, most consequentially, China, as well as the mid-tier developing countries following in their wake. Importantly, China’s embrace of the global trading system, and the after-effects of India as well as Brazil’s economic reforms carried out in the 1990s and turn of the century, reinforced the economic integration trend underway prior to the GFC at global and regional levels.[10] Furthermore, the integrative aspects of the cluster of technologies dubbed the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (Figure 1) was emerging and provided powerful support for economic integration even as the locus of economic activity was shifting.

Yet the GFC lifted the lid on a veritable Pandora’s box of disintegrative forces already in play, culminating most potently in the election of President Donald Trump in the US, and mirrored in Western societies particularly (in Figure 1 ‘Sovereignty’, e.g. Brexit; ‘Exclusion’; and the associated rise of ‘Nationalism’). The Trump administration’s trade policy reflected and amplified this shift, assuming an overt and intensifying mercantilist hue[11], matched by developments in China already in train prior to President Xi’s assumption of leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2013, and subsequent sharp turn towards state capitalism anchored on resurgent State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs).

From the time President Trump unleashed his ‘trade wars’[12] the EU has responded by assuming an explicitly ‘geopolitical’ trajectory, including reviving previously discredited notions of industrial policy couched in terms of economic sovereignty, and labelling China a ‘systemic rival’ as well as a ‘strategic partner’. China’s economic rise and investments in military modernization lent these trends a decidedly militaristic flavour (‘Security’ in Figure 1), while the CCP’s worldwide projection of its authoritarian governance model has challenged Western democracy’s position of relative supremacy. These heightened geopolitical tensions are now driving intense contestation over who will control the cluster of ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (Figure 1) technologies, as well as drawing ‘Military’ (Figure 1) establishments increasingly into the frame. In response Western governments, led by the US and in some cases Australia, are tightening access to their markets for ‘dual-use’ technology-related investments (think Huawei) as well as outward investments by their own firms into rival geopolitical competitors, especially China. On the trade front this is being matched by a proliferation of export control measures over the same cluster of dual-use technologies. At the same time, a backlash against the social implications of some aspects of ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ technologies has been growing in Western societies, and increasingly manifests in control over personal data, feeding into associated policy regimes designed to reign in the power of MNCs driving these technological developments.

Consequently, the COVID-19 ‘Health’ (Figure 1) pandemic interacts with an accelerating process of disintegration in train at least a decade prior to 2020, and has dramatically strengthened those disintegrative forces.

[1] This is my interpretation. It is important to note, however, that officially the Round is still alive and referenced in the WTO’s various committee meetings.

[2] For a page-turning journalist’s account of the ebb and flow of the round see Blustein, P 2009. Misadventures of the most favored nations: clashing egos, inflated ambitions, and the great shambles of the world trade system, PublicAffairs, New York.

[3] This observation was frequently made by the then South African trade minister, Alec Erwin, for whom the author worked (in the Department of Trade and Industry).

[4] Some of which could be subsumed under the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ driver in Figure 1. Veterans of the Round will also remember the US-EU attempt to include competition, investment, and government procurement. This was derailed by a loose coalition of developing countries.

[5] The answer was a resounding ‘no’. This was perhaps best captured in the symbolism of the ‘green room’ (the WTO Director General’s boardroom) in which the quad had traditionally met to hammer out their deals. As the Round’s complexity and coalitional dynamics multiplied, participation in green room deliberations expanded to a core set of systemically-significant developed and developing countries. Pascal Lamy, then the WTO’s Director General, described his approach to mobilizing consensus as one of expanding concentric circles, ie creating a contract zone in the new core group and then progressively rolling it out to the wider membership. See this WTO news item from the July 2008 Geneva Ministerial: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news08_e/meet08_summary_24july_e.htm

[6] See Blustein, Ibid. for a detailed discussion of the proxy causes for this breakdown. As he notes throughout the book, reaching an overall package deal to consummate the Round had become progressively more challenging as the underlying structural fault lines briefly identified above began to manifest.

[7] World Economic Forum, 2015. The High and Low Politics of Trade: Can the World Trade Organization’s Centrality be Restored in a New Multi-Tiered Global Trading System? Geneva.

[8] O’ Neill, J, 2001. ‘Building Better Global Economic BRICs’, Global Economics Paper, no. 66, Goldman Sachs.

[9] O’ Neill, J, Wilson, D, Purushothaman, R and Stupnytska, A, 2005, ‘How Solid are the BRICs?’ Global Economics Paper, no. 134, Goldman Sachs.

[10] See Draper, P, Sally, R, and Alves, P 2009 (eds) The Political Economy of Trade Reform in Emerging Markets, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

[11] While ‘mercantilists’ are best-known in the economics profession for their espousal of balance of trade surpluses — President Trump being an ardent and influential supporter — they were also historically associated with advocating strong militaries to enforce trade prerogatives of the-then colonial powers. See the magisterial Findlay, R & O’Rourke, K 2009, Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

[12] For a critique of this term See Draper, P 2019, op.cit.

Proposal

Disease Containment and Economic Disintegration

National governments have, understandably but also after considerable delay in some countries, followed the advice of their medical and scientific establishments and have moved to self-isolate their countries and citizens. Two positive readings can be taken from this: that scientific advice and medical knowledge is still valued in an increasingly populist world; and that the apex United Nations body charged with cross-border cooperation in international health matters — the World Health Organization (WHO) — is still relevant.

Unfortunately, the good news ends there. With few exceptions implementation of medical advice has led to precipitous disruptions to economic activity and international trade, sparking meltdowns in stock markets, which are generally the quickest to grasp the potential dimensions of the rapid economic slowdown underway across the world. Economists identify three ‘legs’ to this economic disruption: a financial shock as markets plummet off the cliff edge; a supply shock as factories close, workers are sent home, and international trade is curtailed; and a demand shock as companies shut down, trade less with each other, and the new ranks of the unemployed quickly swell. By contrast, the GFC was characterised primarily by a financial shock, ‘curable’ by massive monetary policy stimulus and bank bailouts, and concentrated fiscal support packages, notably in the US. The COVID—19 crisis response has occasioned both massive monetary and fiscal stimulus measures across the world, primarily concentrated in G20, and especially developed, economies. The effect of such actions is seriously blunted so long as economies are in lockdown. Nonetheless, bad as things are in G20 economies, the economic shocks will be felt much more severely in the developing world where governments and societies are far less resilient and have much weaker healthcare systems.[1]

‘Sicken thy neighbour’[2] trade measures have accompanied massive disruptions to supply chains as a consequence of isolation measures implemented across the world. Hoarding, at individual, sub-national, and national levels, of essential medicines, personal protective equipment, respirators, and now food, is taking place in many countries. As is well-known citizens hoarding in the domestic market drives up prices by creating temporary shortages. Similarly, governments’ hoarding by imposing export restrictions creates shortages in international supplies, putting importers at risk and driving up international prices. Unseemly practices, such as shipments destined for one country being intercepted on airport runways and diverted to another owing to more money having been proffered, are mushrooming. Steep price increases for those same medical supplies have occurred, with shortages of critical inputs — often normally sourced from abroad — exacerbating the situation. Transportation restrictions, particularly across borders, have severely interrupted supply chains, and not just for medical equipment. Consequently, governments, notably conservative governments, are compelling companies to produce critical medical products by invoking powers not seen, at least in Western democracies, since the Second World War. Cumulatively these short-term impacts could be devastating for poor consumers, and developing countries, especially when combined with the sudden and massive global joblessness caused by the three-pronged economic crisis induced by COVID-19 self-isolation measures.

Clearly, these are not normal times. Governments should be accountable to their citizens, and individuals will look after their families first. These powerful human impulses are accelerating the breakdown of international cooperation, and are not likely to attenuate until the crisis has passed. Compounding this already grim downward economic spiral is the sharpening of underlying geopolitical tensions, as the major powers, particularly the US and China, seek to cast blame for the onset of the disease and to earn praise for how they have responded. Furthermore, it is not clear when the virus storm clouds will pass, meaning the consequences of global self-isolation could intensify in the months ahead. And possibly most importantly, it is not clear whether the trade shutters will be taken down once the crisis abates.

Overall, the ‘health’ crisis has poured fuel onto the ‘sovereignty’ and ‘nationalism’ fires burning before the disease’s outbreak. And so ‘health security’ is interacting strongly with ‘national security’ and ‘food security’, in ways probably without historical precedent. It is very likely that after the crisis supply chains regarded as critical to maintaining national security (in Figure 1 ‘military’, ‘health’, and ‘food’) will continue to be looked at differently.

So what can the G20 realistically do to arrest the slide towards disintegration, and what credible measures is it willing to take?

G20 Options and Constraints

G20 Trade Ministers COVID-19 Principles

- Temporary application and snapback

- WTO consistency

- Transparency (via WTO notifications)

- Targeted, proportionate, least trade restrictive

- International solidarity

- Assistance for LDCs and SIDS

At their recent virtual meeting G20 trade ministers’ issued a statement setting out how they planned to cooperate to ensure their individual COVID-19 mitigation strategies do not unnecessarily undermine the global trading system. Their official statement contains a number of principles to govern implementation of COVID-19 trade measures, not explicitly stated per se, as shown in the sidebar. These are based on the acknowledgement that each member will implement trade restrictions to manage their own health situations as they see fit, with health understandably taking priority over free trade. These principles anticipate temporary interventions consistent with international rules, implemented transparently and in as least trade-restrictive a manner as possible. Support for poor countries is also pledged.

Taken at face value this is reassuring. Yet as the Global Trade Alert has systematically documented, G20 countries have in the past generally observed their trade commitments in the breach. For example prior to the current crisis the stock of protectionist measures implemented by G20 countries has risen sharply since a pledge for ‘no new protectionist measures’ was undertaken at the London (2009) Summit. Since 2017 protectionism has accelerated. While US trade policy since 2017 has made a large contribution to the recent escalation, this is by no means a purely US story. President Trump’s highly regrettable abandonment of the no-protectionism pledge at the 2018 Berlin G20 Summit thus reflected both new US trade policy reality, and an end to the G20’s charade vis a vis observing the pledge. Furthermore, the massive fiscal expenditures being laid out by developed countries may preclude increases in official development assistance (ODA) flows now, and are very likely to lead to austerity measures down the track, implying ODA reductions down the line.

Therefore, little credence should be attributed to the principles set out at the latest G20 trade ministers meeting. However, to whom trade policy proposals should be addressed if not the G20, is not at all clear. What is clear is that if COVID-19 is not quickly contained and the health threat greatly diminished, ideally removed, then the stock of trade restrictions will accumulate rapidly and become very difficult to disentangle. Accordingly, as levels of alarm rise in the trade policy community there is a mushrooming of policy proposals to G20 trade ministers aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of proliferating COVID-19 related trade restrictions. A selection is provided in Table 1.

With the exception of (1), which transcends health matters, these proposals make for sensible trade policy. Yet viewed from the standpoint of national governments’ protecting their citizens — in other words the politics of pandemic management — some conflict with the pressing needs of ensuring ample domestic medical supplies are available for worst-case scenarios.

The proposals (2 through 4) to eliminate import duties on critical health-related inputs and final products are likely to be patchily implemented since, in every country faced with domestic supply shortages, lobbies are forming around re-shoring supply chains. This means that beyond the crisis trade restrictions are likely to be widely introduced to promote domestic manufacturing. In the next section a framework for containing potential protectionist excesses is proffered.

The advice to terminate export restrictions is sensible trade policy in normal times, and particularly in relation to food which is not in short supply at the global level. But in the current crisis no government accountable to its citizens is likely to tolerate essential medicines or protective equipment being shipped from its jurisdiction in circumstances of acute domestic shortages, or potential shortages based on epidemiological models.

Therefore, little credence should be attributed to the principles set out at the latest G20 trade ministers meeting. However, to whom trade policy proposals should be addressed if not the G20, is not at all clear. What is clear is that if COVID-19 is not quickly contained and the health threat greatly diminished, ideally removed, then the stock of trade restrictions will accumulate rapidly and become very difficult to disentangle. Accordingly, as levels of alarm rise in the trade policy community there is a mushrooming of policy proposals to G20 trade ministers aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of proliferating COVID-19 related trade restrictions. A selection is provided in Table 1.

With the exception of (1), which transcends health matters, these proposals make for sensible trade policy. Yet viewed from the standpoint of national governments’ protecting their citizens — in other words the politics of pandemic management — some conflict with the pressing needs of ensuring ample domestic medical supplies are available for worst-case scenarios.

The proposals (2 through 4) to eliminate import duties on critical health-related inputs and final products are likely to be patchily implemented since, in every country faced with domestic supply shortages, lobbies are forming around re-shoring supply chains. This means that beyond the crisis trade restrictions are likely to be widely introduced to promote domestic manufacturing. In the next section a framework for containing potential protectionist excesses is proffered.

The advice to terminate export restrictions is sensible trade policy in normal times, and particularly in relation to food which is not in short supply at the global level.[3] But in the current crisis no government accountable to its citizens is likely to tolerate essential medicines or protective equipment being shipped from its jurisdiction in circumstances of acute domestic shortages, or potential shortages based on epidemiological models.

Table 1: Select Trade-related Proposals for Managing COVID-19 Health Issues

| Proposal | Sources[1] |

| 1. Fix outstanding trade issues (‘trade wars’) before COVID-19 aggravates negativity in international cooperation | ICC; B20; WHO[2] |

| 2. Import tariff elimination (medicines; medical devices; protective equipment) | GTA[3]; PIIE[4] |

| 3. G20 members should join a WTO pharmaceuticals zero-for-zero import tariffs initiative | DIHK[5] |

| 4. A moratorium on new import tariffs and non-tariff barriers | DIHK[6] |

| 5. Freeze and eliminate export restrictions for essential health and food products | GTA[7] ; PIIE[8] |

| 6. Notifications for new export restrictions lasting beyond 12 months; agree exceptions and procedures | PIIE[9]; DIHK[10] |

| 7. Suspension of WTO and State Aid rules for medicines packages | GTA[11] |

| 8. Market interventions to arrest sudden price spikes | PIIE[12] |

| 9. International Organizations to coordinate PPPs to produce essential health products in select locations based on comparative advantage | World Bank[13]; ICC[14] |

| 10. Control licit and illicit trade in wildlife products to contain risks of cross-species transmission | SCMP[15] |

| 11. Accelerate support for a ‘green deal’ that includes greater control over deforestation, specifically wild animals’ habitat destruction | JDI[16] |

| 12. Support and maintain air cargo flows and develop standards for handling workers | GBC[17] |

| 13. Maintain open sea ports for commercial vessels and ensure rapid crew rotations | ICS[18] |

| 14. Keep digital trade free by extending e-commerce moratorium and concluding the JSI negotiations | DIHK[19] |

Clearly, until governments have a clear picture on national needs relative to covid-19 export restrictions have to be accommodated in realistic future-oriented proposals. In that light, Proposal 6 makes sense as effective implementation would at least have the benefit of signalling forthcoming interventions to trading partners. However, beyond the crisis export restrictions disciplines will need to be revisited in the WTO. Meanwhile, since export restrictions will drive up price levels by reducing availability, those governments with the means to do so will increasingly have recourse to (8) — market interventions to lower prices — but will also need to maintain good relations with key suppliers and associated reciprocal trade arrangements to smooth availability of supplies.

Proposals (7) and (9) are variations on the same theme, which is to subsidise domestic and/or regional production of critical supplies, respectively. In both cases production capacity is a key constraint, being a function of access to finance, critical services and goods inputs, inter alia, as well as intellectual property rights (IPR) although those could conceivably be waived under the Public Health Exception to the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement. Regional production facilities would reside on one or more state’s national territory and could be vulnerable to export restrictions imposed by the host state. Proposals (12) through (14) address the services dimensions related to boosting production capacities, and impact on trade in general, so they have beneficial health and trade policy implications.

Finally, proposals (10) and (11) are sensible health and environmental policies, but face many practical cultural and political obstacles. While the pandemic gives extra impetus to finding solutions to these problems, each is subject to its own complex political economy constraints, which are not amenable to short-term, or potentially medium term, solutions.

Beyond CVD-19: A Trade Policy Framework for Managing Health Crises

It is easy to be critical, more difficult to submit implementable solutions. The proposals reviewed above are useful contributions in the context of the current crisis, even if there are shortcomings, as discussed. A future-oriented policy toolkit that maximises international trade cooperation while optimising governments’ health policy prerogatives requires elaboration of a robust framework.

This framework could be considered a ‘containment’ strategy, designed to minimise the drift towards disintegration by acknowledging the need for free trade to be suspended exceptionally, transparently, and temporarily in response to health crises, and to condition free trade in good times on building crisis-preparedness for the future, in the least trade distorting manner possible.

Trade policy specialists, and particularly international trade lawyers, will note that such flexibilities have long been presaged in WTO law through the GATT’s exceptions clauses (Articles XX and XXI). What those provisions cannot tell states is how to deploy those flexibilities in ways that keep the lights of international cooperation burning, while not tying their hands to respond to health emergencies.

As presaged at the beginning of this briefing, the military-civilian ‘dual-use technology’ concept offers one way of thinking about this. States clearly need to safeguard supplies of essential goods — health and food in this case — needed in crisis times. Since autarky in production of these goods is highly unlikely to be an option for most states owing to production capacity constraints, but also highly undesirable from a trade policy viewpoint since the cross-border value chains that provision modern health systems offer powerful economic benefits in normal times, the framework must involve tailored combinations of import liberalization, stockpiling, and export restrictions in crisis times. From a national point of view it must also entail strategic alliances with trusted trading partners based on complementarities. And it has to encompass a range of services, which traditionally do not receive the attention they deserve in relation to goods trade. Also, states need to establish international trade cooperation frameworks that enable crisis-preparedness at national levels.

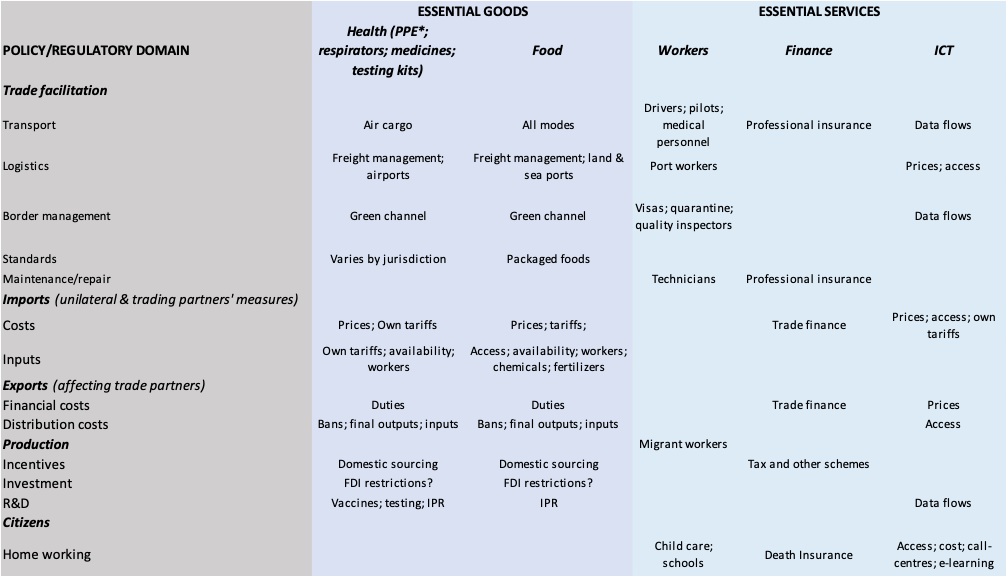

Table 2 provides a high-level elaboration of this framework, building on the proposals presented in Table 1. Services loom large, and cut across many goods sectors, not just health and food. For international trade and domestic commerce to keep functioning transport workers need to be able to move. In relation to trade in health and perishable food products, air transport is emerging as a key constraint. Yet most freight is sea-borne, and so shipping workers similarly need to be able to move relatively freely across international borders. If they cannot, then international trade would truly break down, with catastrophic consequences. Similarly, trade finance is emerging as a key constraint in some jurisdictions as many businesses are confronted with sudden and severe cash flow problems. Insurance regimes of various kinds are also needed, and need retrofitting for crisis preparedness, primarily at the national level. It is not possible to contemplate home-working without access to appropriate bandwidth and software, and without adequate home-working arrangements there would be many more unemployed people. Call-centres have emerged as critical services that underpin many businesses, meaning that quarantine arrangements for their workers have international ramifications. For international trade to function effectively, data needs to keep flowing seamlessly and cost-effectively across borders.

Table 2: A National Trade Policy ‘Containment Framework’ for Countries Planning for Pandemics beyond COVID-19

Sources: Various reports cited in Table 1, Global Services Coalition[1], and author’s elaboration.

* PPE = Personal Protective Equipment

As documented in the GTA[2], policy barriers to flows of essential health products raise prices, restrict availability, and sharpen the breakdown of international trade cooperation. Lack of national supplies, not surprisingly, has induced some governments to incentivise domestic production, while some are restricting inward foreign direct investment into sectors now deemed critical for national security and in respect of which ensuring domestic ownership may be a priority — to avoid potentially predatory behaviours as witnessed in the aftermath of the GFC.

Therefore, a set of principles to guide this framework should be elaborated. Four principles provided by the OECD in its COVID-19 briefing are a good starting point. They refer specifically to support granted to domestic stakeholders in crisis circumstances, averring that such support should be:[3]

- transparent —including with regard to the terms of any support through the financial system;

- non-discriminatory amongst similarly affected firms and targeted at those experiencing the most disruption, while avoiding rescue for those who would have failed absent the pandemic;

- time bound, and reviewed regularly to ensure that it is hitting its target and remains necessary; and

- targeted at consumers, leaving them for to decide how to spend any support, rather than tied to consumption of specific input and final goods and services

Concluding Recommendations

The framework presented in Table 2 is inherently a national one, for unilateral action. Translating it into the international, and particularly G20, terrain is challenging, but several preliminary recommendations emerge:

- G20 trade ministers should seed the following plurilateral initiatives in the WTO:

- Reduce and/or eliminate import duties for critical health equipment, pharmaceuticals, and related inputs necessary for these cross-border value chains to function smoothly. This would enable construction of stockpiles for future crises, and production capacity — whether on a national or regional level. Given that this primarily concerns import duties, the agreement should be pursued on a Most-Favoured Nation[4] (MFN) basis, once critical mass[5] amongst the major trading partners has been achieved.

- Initiate a plurilateral negotiation amongst partners in respect of containing and managing subsidisation of domestic firms, while ensuring sufficient policy space to prepare domestic and regional response capacities for future health crises.[6] Subsidies reform was a critical issue on the WTO reform agenda prior to COVID-19, and is now much more urgent owing to the rapid accumulation of subsidisation measures across the major economies, as governments roll out vast monetary and fiscal support to domestic firms to prevent economic collapse. Importantly, this negotiation should encompass both goods and services.

- Similarly, G20 trade ministers should initiate a multilateral discussion in the WTO to bring greater clarity to governance of GATTs exceptions clauses, specifically:

- Those GATT provisions relating to export restrictions

- The security exception, which was under much scrutiny prior to COVID-19 owing to some member states, notably the US, making increasing use of them.

In making these recommendations I am very cognisant that getting anything done in the WTO is a major challenge. Nonetheless, the G20 has supported a WTO reform agenda, which now needs to be updated to reflect COVI-19 exigencies, in pursuance of which these recommendations could provide a roadmap. The time for the G20 to act is now.

[1] Global Services Coalition, 1 April 2020, ‘Ensuring Resilience of Global Supply of Essential Services in Combating COVID-19’, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/gsc_statement_e.pdf

[2] Global Trade Alert, 2020, op.cit.

[3] OECD, 2020, op.cit, P9.

[4] Meaning that ensuing tariff reductions would be multilateralised, so that non-participating countries could also benefit.

[5] Meaning that a sufficient volume of trade is involved so that the problem of free-riding is minimized.

[6] See OECD, 2020, op.cit, P8 for a brief discussion of this imperative.

Sources: Various reports cited in Table 1, Global Services Coalition[1], and author’s elaboration.

* PPE = Personal Protective Equipment

As documented in the GTA[2], policy barriers to flows of essential health products raise prices, restrict availability, and sharpen the breakdown of international trade cooperation. Lack of national supplies, not surprisingly, has induced some governments to incentivise domestic production, while some are restricting inward foreign direct investment into sectors now deemed critical for national security and in respect of which ensuring domestic ownership may be a priority — to avoid potentially predatory behaviours as witnessed in the aftermath of the GFC.

Therefore, a set of principles to guide this framework should be elaborated. Four principles provided by the OECD in its COVID-19 briefing are a good starting point. They refer specifically to support granted to domestic stakeholders in crisis circumstances, averring that such support should be:[3]

- transparent —including with regard to the terms of any support through the financial system;

- non-discriminatory amongst similarly affected firms and targeted at those experiencing the most disruption, while avoiding rescue for those who would have failed absent the pandemic;

- time bound, and reviewed regularly to ensure that it is hitting its target and remains necessary; and

- targeted at consumers, leaving them for to decide how to spend any support, rather than tied to consumption of specific input and final goods and services

Concluding Recommendations

The framework presented in Table 2 is inherently a national one, for unilateral action. Translating it into the international, and particularly G20, terrain is challenging, but several preliminary recommendations emerge:

- G20 trade ministers should seed the following plurilateral initiatives in the WTO:

- Reduce and/or eliminate import duties for critical health equipment, pharmaceuticals, and related inputs necessary for these cross-border value chains to function smoothly. This would enable construction of stockpiles for future crises, and production capacity — whether on a national or regional level. Given that this primarily concerns import duties, the agreement should be pursued on a Most-Favoured Nation[4] (MFN) basis, once critical mass[5] amongst the major trading partners has been achieved.

- Initiate a plurilateral negotiation amongst partners in respect of containing and managing subsidisation of domestic firms, while ensuring sufficient policy space to prepare domestic and regional response capacities for future health crises.[6] Subsidies reform was a critical issue on the WTO reform agenda prior to COVID-19, and is now much more urgent owing to the rapid accumulation of subsidisation measures across the major economies, as governments roll out vast monetary and fiscal support to domestic firms to prevent economic collapse. Importantly, this negotiation should encompass both goods and services.

- Similarly, G20 trade ministers should initiate a multilateral discussion in the WTO to bring greater clarity to governance of GATTs exceptions clauses, specifically:

- Those GATT provisions relating to export restrictions

- The security exception, which was under much scrutiny prior to COVID-19 owing to some member states, notably the US, making increasing use of them.

In making these recommendations I am very cognisant that getting anything done in the WTO is a major challenge. Nonetheless, the G20 has supported a WTO reform agenda, which now needs to be updated to reflect COVI-19 exigencies, in pursuance of which these recommendations could provide a roadmap. The time for the G20 to act is now.

[1] Global Services Coalition, 1 April 2020, ‘Ensuring Resilience of Global Supply of Essential Services in Combating COVID-19’, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/gsc_statement_e.pdf

[2] Global Trade Alert, 2020, op.cit.

[3] OECD, 2020, op.cit, P9.

[4] Meaning that ensuing tariff reductions would be multilateralised, so that non-participating countries could also benefit.

[5] Meaning that a sufficient volume of trade is involved so that the problem of free-riding is minimized.

[6] See OECD, 2020, op.cit, P8 for a brief discussion of this imperative.

[1] GTA = Global Trade Alert; PIIE – Petersen Institute for International Economics; DIHK = Deutscher Industrie-und Handelsmammertag; ICC = International Chambers of Commerce; B20 = Business 20; WHO = World Health Organization; SCMP = South China Morning Post; JDI = Jacques Delors Institute; GBC = Global Business Coalition; ICS = International Chamber of Shipping.

[2] B20, ICC, WHO, 23 March 2020, ‘Need for coordinated action by G20 leaders in response to the COVID-19 pandemic – an unprecedented health and economic crisis‘, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/b20_icc_statement_e.pdf

[3] Evenett, S 2020, Op.cit.

[4] There are many good resources on the Institute’s website, available here: https://www.piie.com/research/economic-issues/coronavirus. I have drawn on the works of Chad Bown, Anabel Gonzalez, and Cullen S. Hendrix in particular.

[5] DIHK, 26 March 2020 ‘Corona – Trade Policy Challenges’, available at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/dihk_statement_e.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] Op.cit.

[8] Op.cit.

[9] Op.cit.

[10] Op.cit.

[11] Op.cit.

[12] Op.cit.

[13] The World Bank also has a dedicated Trade and COVID-19 page, available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/trade-and-covid-19. See in particular Mattoo, A and Ruta, M 2020 ‘Viral Protectionism in the time of coronavirus’, March 27, at https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/viral-protectionism-time-coronavirus.

[14] ICC letter to His Majesty King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, March 12, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/icc-letter-to-his-majesty-king-salman-bin-abdulaziz-al-saud.pdf

[15] McCarthy, S 2020 ‘Coronoavirus: what next for China’s wildlife trade ban?’ South China Morning Post, 8 April.

[16] Pons, G 2020, ‘COVID-19 Crisis: An Occasion to Accelerate the Transition Towards a new Development Model?’, mimeo.

[17] Global Business Coalition, March 19 2020, ‘GBC Members Call for measures to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on supply chains’, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/gbc_statement_e.pdf

[18] International Chamber of Shipping, March 19 2020, ‘Joint Open Letter to United Nations agencies from the global maritime transport industry’, At https://www.ics-shipping.org/news/press-releases/view-article/2020/03/19/joint-open-letter-to-united-nations-agencies-from-the-global-maritime-transport-industry

[19] Op.cit.

[1] GTA = Global Trade Alert; PIIE – Petersen Institute for International Economics; DIHK = Deutscher Industrie-und Handelsmammertag; ICC = International Chambers of Commerce; B20 = Business 20; WHO = World Health Organization; SCMP = South China Morning Post; JDI = Jacques Delors Institute; GBC = Global Business Coalition; ICS = International Chamber of Shipping.

[2] B20, ICC, WHO, 23 March 2020, ‘Need for coordinated action by G20 leaders in response to the COVID-19 pandemic – an unprecedented health and economic crisis‘, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/b20_icc_statement_e.pdf

[3] Evenett, S 2020, Op.cit.

[4] There are many good resources on the Institute’s website, available here: https://www.piie.com/research/economic-issues/coronavirus. I have drawn on the works of Chad Bown, Anabel Gonzalez, and Cullen S. Hendrix in particular.

[5] DIHK, 26 March 2020 ‘Corona – Trade Policy Challenges’, available at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/dihk_statement_e.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] Op.cit.

[8] Op.cit.

[9] Op.cit.

[10] Op.cit.

[11] Op.cit.

[12] Op.cit.

[13] The World Bank also has a dedicated Trade and COVID-19 page, available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/trade-and-covid-19. See in particular Mattoo, A and Ruta, M 2020 ‘Viral Protectionism in the time of coronavirus’, March 27, at https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/viral-protectionism-time-coronavirus.

[14] ICC letter to His Majesty King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, March 12, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/icc-letter-to-his-majesty-king-salman-bin-abdulaziz-al-saud.pdf

[15] McCarthy, S 2020 ‘Coronoavirus: what next for China’s wildlife trade ban?’ South China Morning Post, 8 April.

[16] Pons, G 2020, ‘COVID-19 Crisis: An Occasion to Accelerate the Transition Towards a new Development Model?’, mimeo.

[17] Global Business Coalition, March 19 2020, ‘GBC Members Call for measures to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on supply chains’, at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/gbc_statement_e.pdf

[18] International Chamber of Shipping, March 19 2020, ‘Joint Open Letter to United Nations agencies from the global maritime transport industry’, At https://www.ics-shipping.org/news/press-releases/view-article/2020/03/19/joint-open-letter-to-united-nations-agencies-from-the-global-maritime-transport-industry

[19] Op.cit.

[1] Available at https://www.globaltradealert.org/

[2] Evenett, SJ and Fritz, J, 29 November 2018, ‘Brazen Unilateralism: The US-China Tariff War in Perspective’, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

[3] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2020 ‘COVID-19 and international trade: Issues and Actions’, at https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128542-3ijg8kfswh&title=COVID-19-and-international-trade-issues-and-actions.

[1] Eichengreen, B 2020 ‘The most serious crisis of all’, East Asia Forum, 12 April.

[2] Global Trade Alert, 2020, Tackling Coronavirus: The Trade Policy Dimension, University of St Gallen, 11 March.

This Policy Brief was originally published here.