One of the challenges that population aging poses is to ensure that people have an adequate level of saving for old age. While individuals are increasingly being asked to take more responsibility for their old-age saving, the evidence suggests that low levels of financial literacy are prevalent across the world and that the effectiveness of financial incentives that are offered to encourage people to enhance their retirement saving seems somewhat limited. We propose a number of policies that address these challenges with the aim of ensuring the financial wellbeing of the elderly in their retirement.

Challenge

Population aging is now a pressing issue not only for advanced economies but also for developing economies. In particular, in many countries in Asia, population aging is progressing at an unprecedented rate and is occurring at a relatively early stage of development, which gives these countries limited time and opportunity to prepare themselves for the needs of an aged society.

One of the challenges that population aging poses is the adequacy of saving for old age. While public pension programs continue to play an important role in people’s old age saving in most developed countries, the fiscal sustainability of such programs is increasingly being challenged as a result of population aging. In response, governments have been introducing measures that encourage individuals to take more responsibility for securing their financial wellbeing in old age, but there remains room for further efforts. Moreover, increases in life expectancy are making it harder to ensure the adequacy of old-age saving. Turning to the case of the developing world, many emerging and developing countries are not yet equipped with an adequate system of public pensions, and people continue to rely largely on family support for their old age.

Another issue that is related but at the other extreme is the slower than expected wealth decumulation rate of the elderly observed in many countries across the world. Indeed, there is a growing literature that examines why the elderly tend to hold onto their wealth into very old age, and several alternative explanations have been put forward to explain this puzzle, including precautionary saving and bequest motives (1). For example, using data on Japan, Horioka and Niimi (2017) and Niimi and Horioka (2018) find that it is due more to saving for precautionary purposes arising from lifespan uncertainty and uncertainty about future medical and long-term care expenses than to saving for bequest motives. One of the important implications of such a phenomenon is that the wellbeing of the elderly is being adversely affected because they are not able to enjoy as high a standard of living as they can afford because of their perceived need to save so much for precautionary purposes. The consumption and saving behavior of the elderly has profound macroeconomic implications, and its importance will increase given that the share of household wealth held by the elderly will invariably increase along with population aging. For example, in Japan, the most aged society in the world, almost 70% of total financial wealth is held by households whose heads are aged 60 or above and more than 90% of total financial net wealth is held by such households. (2)

Proposal

One of the solutions we propose for the above challenges is to enhance people’s financial literacy to help them plan better for retirement. Other solutions include financial incentives that encourage individuals to be better prepared for old age and financial innovations that allow the elderly to decumulate their wealth more rapidly without sacrificing their peace of mind.

Proposal 1: Enhance financial literacy

The importance of having an adequate level of financial literacy has been widely recognized and emphasized across the world in recent years. Its importance in the context of ensuring the adequacy of saving for old age is no exception. Van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie (2012), for example, provide evidence of a strong association between financial literacy and the level of wealth. They identify two channels through which financial literacy may facilitate wealth accumulation: (i) financial literacy increases the likelihood of investing in the stock market, allowing individuals to benefit from the equity premium; and (ii) financial literacy is also positively related to retirement planning, and having a savings plan helps individuals accumulate wealth. Given that the fiscal sustainability of public pension programs is being challenged as a result of population aging, individuals are being increasingly encouraged to take more responsibility for managing their own retirement saving, mainly through a general shift from defined-benefit to defined-contribution pension plans. Indeed, a growing number of products are being offered for retirement saving by increasingly complex financial markets. Thus, having an adequate level of financial literacy is becoming more important than ever.

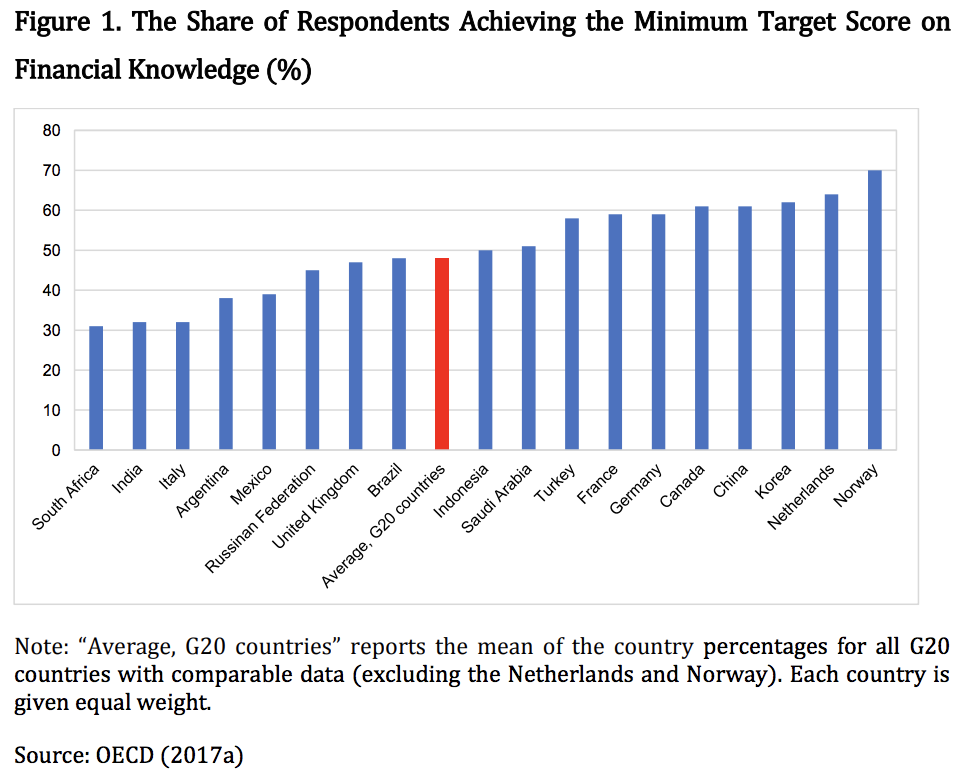

Recent years have witnessed growing efforts to assess the levels of financial literacy of the population. For instance, the OECD International Network on Financial Education (INFE) has developed a survey instrument that can be used to measure financial literacy. Its core questions cover financial knowledge, behavior, and attitudes that are thought to be necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial wellbeing (OECD, 2017a). According to the findings obtained by the OECD/INFE survey, on average, fewer than half (about 48%) of adults in the G20 countries could answer 70% of the financial knowledge questions correctly (the minimum target score) (see Figure 1). Similarly, a growing literature on financial literacy underscores the fact that low levels of financial literacy are prevalent across the world (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014). Moreover, women are generally found to have less financial knowledge than men: on average, only about 43% of women in the G20 countries achieved the minimum target score, while about 54% of men did so (OECD, 2017a).

To address the prevalence of financial illiteracy across the world, we propose the following three policies:

Policy 1: Ensure that people have an equal opportunity to access financial education at a young age.

Policy 2: Enhance concerted and coordinated efforts among the ministry responsible for education, financial regulatory authorities, and the private sector (financial institutions) to develop appropriate financial education programs.

Policy 3: Enhance our understanding of the effectiveness of financial education at school so that it can be better designed and delivered in a more efficient and effective way.

One way of enhancing the general level of financial literacy in the long run is to ensure that people have an equal opportunity to access financial education at a relatively early stage of their lives. In response to the recognition that basic financial literacy is an essential life skill, the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has been assessing the financial literacy of 15-year-old students since PISA 2012. According to PISA 2015, far too many students around the world were found to be failing to attain a baseline level of proficiency, suggesting that greater investments in financial literacy from a young age are needed (OECD, 2017b). However, to develop and design appropriate financial education programs, concerted and coordinated efforts among the key stakeholders, including the ministry responsible for education, financial regulatory authorities, and the private sector (financial institutions) are needed. At the same time, we still know too little about what should be taught in financial education and how and when it should be delivered to children. We therefore need to conduct more empirical analyses of the effectiveness of existing financial education programs, identify good (and bad) practices across the world, and encourage countries to share their experiences so that financial education can be better designed and delivered in a more efficient and effective way.

Proposal 2: Improve the design of financial incentives to save for retirement

The provision of financial incentives has long been a common tool for governments to boost saving, and the promotion of saving for old age is no exception. In light of the growing problem of the fiscal sustainability of public pension programs due to population aging, governments have been introducing various financial incentives to enhance participation in, and contributions to, retirement saving plans to complement public pensions and to enhance overall saving for old age, thereby making people take more responsibility for their financial wellbeing after retirement. Financial incentives generally take the form of both tax incentives and non-tax incentives: tax incentives, the most common type of such measures, provide favorable tax treatment to retirement saving as compared to other types of saving, while non-tax incentives, which are more recent, include matching contributions and fixed nominal subsidies paid into the pension accounts of eligible individuals (OECD, 2018). However, given that these measures imply a fiscal cost to governments, it is important that the intended objectives of the measures be met without causing an excessive fiscal burden on governments. There has thus been an increasing number of studies that assess the effectiveness of financial incentives introduced in various countries (3). The empirical evidence from this literature seems somewhat mixed, but much of the evidence tends to show that the effectiveness of tax incentives as a tool for enhancing “new” saving is relatively limited as saving in pension accounts tends to crowd out saving in taxable accounts (e.g., Attanasio and DeLeire, 2002; Chetty et al., 2014). Similarly, the incentive effects of employer matching contributions are found to be rather small (e.g., Mitchell, Utkus, and Yang, 2007). These findings therefore suggest that the design of financial incentives needs to be improved to enhance retirement saving. Toward this end, we propose the following two policies:

Policy 4: Incorporate automatic enrollment and automatic escalation of contributions in pension plans.

Policy 5: Make offered financial incentives simple and stable.

In our view, the most effective way of encouraging individuals to save more for retirement is to increase their level of financial literacy, as discussed in Proposal 1, but a complementary approach is to get the design of the programs right. For example, Chetty et al. (2014) find that automatic employer contributions to retirement accounts are more effective at raising saving rates than tax subsidies, particularly among passive savers who are least prepared for retirement. Similarly, Benartzi and Thaler (2007) argue that automatic enrollment in company pension plans will lead to broader participation than requiring workers to fill out a form and bring it to a particular office in order to enroll. Another solution is the automatic escalation of contributions, and the Save for Tomorrow program, which pre-commits workers to save more every time they receive a pay raise, is a concrete example of this approach. Many retirement plan administrators in the US have adopted this program, and Benartzi and Thaler (2007) show that a large share of workers signed up for the program when it was offered to them and that it led to sharp increases in saving for retirement. Given that people have a tendency to save too little for their retirement in the first place as a result of inertia, procrastination, and myopia, making the default setting of pension plans automatic enrollment is likely to be more effective at raising saving for retirement. We also propose that financial incentives, whether tax or non-tax, need to be simple and stable to meet the intended objective of these measures. Programs that are complex with many options and/or with frequent changes are harder for people to comprehend, and they will be reluctant to sign up for them.

Proposal 3: Facilitate the decumulation of wealth after retirement

One of the puzzles about the saving behavior of the elderly identified in empirical studies is that the elderly do not decumulate their wealth at all or that they do not decumulate their wealth as rapidly as predicted theoretically (e.g., Horioka, 2010; De Nardi, et al., 2016; Horioka and Niimi, 2017; and Niimi and Horioka, 2018). The three leading explanations for this phenomenon are that the elderly want to leave bequests to their children, that they are worried about future medical and long-term care expenses and/or about running out of wealth before they die, and that financial products that would facilitate wealth decumulation are not available. A consensus has not been reached about the relative importance of these explanations, but they are all undoubtedly important to at least some extent.

Here we wish to focus on what financial products can be used to make it easier for the elderly to decumulate their wealth in order to finance living expenses during retirement, and thus we propose the following four policies:

Policy 6: Introduce financial products that make it easier for the elderly to decumulate their wealth.

Policy 7: Ensure that such financial products are safe, properly designed, and actuarially fair.

Policy 8: Make information on such financial products more readily available.

Policy 9: Enhance the capacity of the relevant stakeholders to assist and guide the elderly with deteriorating cognitive skills to make appropriate financial decisions.

One financial innovation that will help is private lifetime annuities, which will enable the elderly to increase their spending on living expenses without their having to worry about running out of wealth before they die. Another closely related financial innovation is reverse mortgages (also called home equity conversion mortgages), whereby the elderly sell their homes to another party subject to the provision that they be allowed to continue living in the house until they die. In effect, the elderly borrow from the party purchasing their homes using their homes as collateral. The advantage of this product is that it allows the elderly to draw down their housing wealth while continuing to live in their homes until death. Since many elderly have a strong preference for living in familiar surroundings until their death, this is an especially attractive financial product. A more general financial innovation is home equity loans whereby homeowners borrow using their homes as collateral. Such loans have shown rapid growth in the United States (US), as documented by Canner, Durkin, and Luckett (1998).

Nevertheless, many of these financial products are currently available only in a small number of countries. For example, reverse mortgages are available only in such countries as Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, Taiwan, and the US. Moreover, even in countries in which these products are available, their take-up rate is low. For example, in the case of the US where such products are relatively more available, Benartzi, Previtero, and Thaler (2011) find that the take-up rate for annuities was only about 13% in their sample of enrollees in defined-benefit company pension plans. Similarly, Nakajima and Telyukova (2017) find that the take-up rate for reverse mortgages among eligible homeowners was only about 2% in 2013.

There is a large literature that examines possible reasons for the low take-up rate of private annuities–the so-called “annuity puzzle.” Benartzi, Previtero, and Thaler (2011), for example, find that the low take-up rate for private annuities is due partly to the time and trouble needed to decide on an annuity supplier and an annuity plan. Among the few studies that look at the case of reverse mortgages, Nakajima and Telyukova (2017) find that the low take-up rate for reverse mortgages is due partly to high loan costs, especially the high mandatory insurance costs. These findings suggest that even in countries where these financial products are already available, there is room for making their terms more favorable and for making information on such products more readily available to enhance the take-up rate. It is equally important, however, that people have an adequate level of financial literacy to fully understand and maximize the benefits of these somewhat complex financial products in order to enhance their financial wellbeing during retirement.

Lastly, a growing challenge of population aging in recent years is to ensure that the elderly make sound financial decisions throughout their lives even if they face growing difficulties with cognition as they get older. It is thus important to accommodate the needs of the elderly by enhancing the capacity of the relevant stakeholders (e.g., public pension officers, regulators, financial advisors, financial institutions, etc.) to assist and guide the elderly with deteriorating cognitive skills in their financial decision making.

References

• Attanasio, O. P. and T. DeLeire (2002) “The Effect of Individual Retirement Accounts on Household Consumption and National Saving,” Economic Journal, 112 (481), pp. 504- 538.

• Benartzi, S., A. Previtero, and R. H. Thaler (2011), “Annuitization Puzzles,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), pp. 143-164.

• Benartzi, S. and R. H. Thaler (2007), “Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), pp. 81-104.

• Canner, G. B., T. A. Durkin, and C. A. Luckett (1998), “Recent Developments in Home Equity Lending,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, 84, pp. 241-251.

• Chetty, R., J. N. Friedman, S. Leth-Petersen, T. H. Nielsen, and T. Olsen (2014), “Active vs. Passive Decisions and Crowd-Out in Retirement Savings Accounts: Evidence from Denmark,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(3), pp. 1141-1219.

• De Nardi, M., E. French, and J. B. Jones (2016), “Saving After Retirement: A Survey,” Annual Review of Economics, 8, pp. 177-204.

• Horioka, C. Y. (2010), “The (Dis)saving Behavior of the Aged in Japan,” Japan and the World Economy, 22(3), pp. 151-158.

• Horioka, C. Y. and A. Terada-Hagiwara (2012), “The Determinants and Long-term Projections of Saving Rates in Developing Asia,” Japan and the World Economy, 24(2), pp. 128-137.

• Horioka, C. Y. and Y. Niimi (2017), “Nihon no Koureisha Setai no Chochiku Koudou ni kansuru Jisshou Bunseki (An Empirical Analysis of the Saving Behavior of Elderly Households in Japan),” Keizai Bunseki (Economic Analysis), 196, pp. 29-47 (in Japanese).

• Lusardi, A. and O. S. Mitchell (2014), “The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5-44

• Mitchell, O. S., S. P. Utkus, and T. Yang (2007), “Turning Workers into Savers? Incentives, Liquidity, and Choice in 401(k) Plan Design,” National Tax Journal, 60(3), pp. 469-489.

• Nakajima, M. and I. A. Telyukova (2017), “Reverse Mortgage Loans: A Quantitative Analysis,” Journal of Finance, 72(2), pp. 911-950.

• Niimi, Y. and C. Y. Horioka (2018), “The Wealth Decumulation Behavior of the Retired Elderly in Japan: The Relative Importance of Precautionary Saving and Bequest Motives” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, forthcoming, DOI: 10.1016/j.jjie.2018.10.002

• OECD (2017a), G20/OECD INFE Report on Adult Financial Literacy in G20 Countries, Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD (2017b), PISA 2015 Results (Volume IV): Students’ Financial Literacy, Paris: OECD Publishing.

• OECD (2018), Financial Incentives and Retirement Savings, Paris: OECD Publishing.

• Van Rooij, M. C. J., A. Lusardi, and R. J. M. Alessie (2012), “Financial Literacy, Retirement Planning and Household Wealth,” Economic Journal, 122 (560), pp. 449-478.