The rules-based Multilateral Trading System (MTS) is in need of reforms. Reasons include the consensus principle leading to stuck negotiations as well as bilaterals and plurilaterals; and the WTO DSM stalemate hindering speedy resolution of trade frictions. To improve the WTO’s effectiveness, we suggest a hierarchical framework for plurilaterals to support developing nations. We also propose a comparative analysis of the major plurilateral bodies to improve the WTO’s consensus-based decision-making process. To strengthen the rules-based MTS, we propose a G20 pledge against discriminatory trade policies along with a mechanism facilitated by G20 and the regional blocs to effect WTO reforms.

Challenge

The World Trade Organization (WTO) has been under pressure for quite some time. While the rules as such are widely accepted as the welfare enhancing nature of trade is principally recognized and endorsed by all member countries, they are not obeyed thoroughly and progress in liberalization is even more unlikely. This has its reasons in procedural flaws, institutional deficiencies and growing distrust among members. Problems such as the vetoenabling consensus principle and the impasse over the WTO Appellate Body (AB) appointments resulted in a dysfunctional Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM), eroding the credibility of the world trading order. Major trade frictions, especially the high-profile US-China trade war, highlighted two major problems: the DSM is not swift enough in resolving trade disputes and the delays result in huge financial losses for businesses; and the WTO lacks adequate capacity to deal with nuanced policies concealing subsidies and forcing technology

transfer.

With the Multilateral Trading System (MTS) facing these challenges, bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTA) have gained ground. These pacts are becoming platforms for countries to discuss and agree on WTO-plus matters including those related to digital trade and health. The difficulties in taking forward the consensus-based decision-making process have also led to open plurilaterals or Joint Statement Initiatives (JSI), reflecting the dilemma. Only an agile and flexible rules-based MTS with resilient procedures can respond dynamically and effectively to the multitude of challenges faced by the global economy that is in a constant state of flux due to reasons—both economic and non-economic. While discussions on plurilaterals and RTAs are underway to address some of these issues, the moot point is to ensure the assimilation of multilateral trade negotiations as well as the JSIs and regionals happens within the WTO itself.

The WTO’s inadequate capacity is making it difficult for the global body to effectively address its “core” functions–i.e., “trade negotiations”; “dispute settlement”; “implementation and monitoring multilateral trade pacts”; and “supporting development and trade capacity building” (WTO website). This paper focuses on the first two functions: strengthening the negotiation process and achieving substantial agreements, and; making dispute settlement become more effective and less vulnerable. The logic is that the WTO is facing relatively greater challenges in addressing those two functions, owing to the lack of any multilateral pact other than the Trade Facilitation Agreement since its inception and the deadlock over the WTO AB appointments.

The ramifications of the current global economic situation, including the supply chain disruptions have provided justification for governments to shift from multilateralism and adopt nationalist, protectionist and unilateral policies and measures, as well as go for bilateral and regional agreements, thus accelerating the ongoing pattern of slowbalization (Footnote 1). In addition, food, fuel, and fertilizer shortages as well as an impending global recession lends greater importance to the need to boost those functions to maintain rulesbased global trade governance and provide certainty.

Proposals for the G20

The G20 has recognized the need for updating the global trade rulebook and has committed itself to working with WTO Members to reform the global trade body in an inclusive, transparent, open, fair and equitable manner. With developing countries constituting a majority of the WTO Members, it is important for the G20 to ensure that WTO reform measures address the developmental challenges faced by the Global South.

In this context, the challenges can be distinguished into two categories: substance and procedures. Whereas the substance–e.g., the “Most Favored Nation” principle), national treatment, and reciprocity–is mostly accepted, although not necessarily enforced, the

procedural weaknesses contribute to the lack of enforcement of the substance. We, therefore, will focus on procedures. Given this backdrop, we suggest that in order to effectively address the challenges—such as those related to difficulties in consensus-based decision-making and a weakened DSM—that are at the core of the rules-based MTS, the G20 members should consider the following proposals for reforming the WTO:

1. Ways to make plurilaterals successful and effective within the ambit of the MTS using a hierarchical framework;

2. (a) An analysis of RTAs to help them evolve into multilateral agreements; (b) a structural and functional analysis of select multilateral institutions and their decision-making processes.

3. The deployment of a mechanism facilitated by the G20 and regional blocs (political, economic and trade) to take forward the WTO reforms with a particular focus on ending the DSM-related impasse.

Recommendations

1: Refining the procedures of plurilaterals

The WTO’s effectiveness with regard to negotiations for multilateral trade agreements has been reduced significantly by the obligation of consensus-based decision-making and the attendant constraints (CRS: Cimino-Isaacs and Fefer, 2021); this becomes more obvious the more diverse membership is. Therefore, the decision of a growing number of members to join plurilaterals/JSIs within the rules-based MTS could be seen as an attempt to overcome the negative effects of the consensus-based decision-making. However, since these plurilaterals only witness a low participation of developing countries (Akman et al., 2021), they should be made more accommodative to the multiple interests of the membership (WTO, 2021a; Geneva Trade Platform’s website).

Additionally, there is a need to settle the dispute around the legitimacy of the JSIs. The controversy around whether these “open” JSIs are “a new set of Agreements which are neither multilateral agreements nor Plurilateral Agreements”—as defined in Article II.3 of the Marrakesh Agreement”—or are entirely legitimate and compliant with the WTO’s fundamental principles, needs to be settled by amending the concerned rules, as opposed to efforts by some Members to do so through modifications to schedules (WTO, 2021a; Akman et al, 2021).

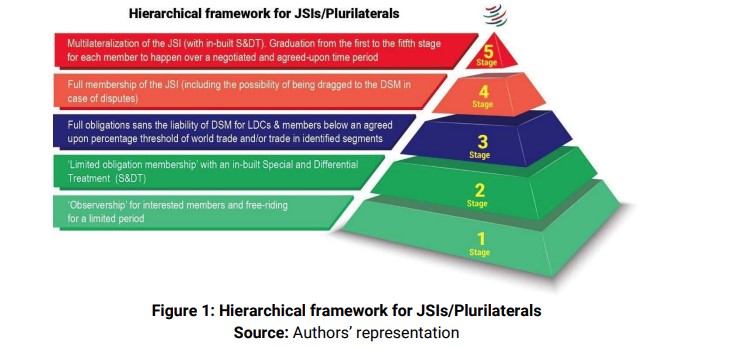

Once that issue is settled, a hierarchy of obligations can be formulated through a multilateral agreement for the WTO Membership to provide them an opportunity to incrementally join any JSI negotiation based on their preparedness to do so and then gradually enter the different stages. Several leading economies in the G20 are participants in the JSIs. The G20, therefore, could suggest a hierarchical framework (See Figure 1) that can provide sufficient flexibility to WTO Members from the Global South. This paper contends that only a JSI process embedded with adequate flexibilities can ensure greater and effective participation of the Global South in the plurilaterals. Of course, coalition-building to protect the interests of the developing world, generating greater awareness about the benefits of the JSIs, and developing capacities in the Global South can also help strengthen the efforts in this context.

1. The first stage of this process could be providing the interested member the freedom to join a JSI it is interested in purely as an Observer. During the period of “Observership”, the member would be accorded the benefit of free-riding for a limited period, if desired by it;

2. The second stage could be a “limited obligation membership” which has an in-built Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT). With S&DT being a major incentive for economies in the Global South to take part in the WTO processes to boost their trading prospects and simultaneously address developmental challenges, we suggest that “open, transparent and non-discriminatory” plurilaterals/JSIs should also incorporate effective S&DT norms for developing countries to enable such innovative efforts to address various inequities in the existing global trade architecture;

3. The third stage could be full obligations sans the liability of the DSM to the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and those members below an agreed upon percentage threshold of world trade and/or trade in the segments identified by the JSI participants (e.g., e-commerce) or global investment threshold for investment facilitation talks. Those crossing the set limit(s) will not be eligible to be exempted from being subjected to the DSM in instances of violations/disputes;

4. The penultimate stage could be full membership of the JSI, including the possibility of being dragged to the DSM in case of disputes;

5. This will be followed by the last stage (i.e., multilateralization of the JSI). The important principle in this context is the acceptance of flexibility and the S&DT concept.

The graduation from the first to the final stage for each member can happen over a negotiated and agreed-upon period of time. If the country fails to move to the next stage within the committed deadline, the membership would consider the consequences following due process.

The basis for this proposal includes the following factors: (i) carve-outs even for developed members exist in present set of agreements; (ii) S&DT provisions are a recognition of the multilayered structure of the WTO membership on the basis of the economic status of members; and (iii) existence of the “peace clause” is in effect an acknowledgment of impracticalities of the extant provisions and point to the need for their modification. Moreover, these accommodative factors are an indication of the need to continuously ensure adequate flexibilities to boost the preparedness of members to effectively participate and gain from a rules-based multilateral trading system that is resilient and sustainable.

2(a): Analysis of RTAs to help them evolve into multilateral agreements:

The MTS is faced with the proliferation of bilateral and RTAs, which often become platforms for their partner countries to discuss matters that have not been successfully discussed in WTO negotiations. These trade agreements, including those between the developed and developing countries have commitments that are “deeper” than those made at the WTO (WTO: Crawford and Fiorentino, 2005).

Further, mega-trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have also come into force. These agreements, essentially being regional in nature, may lead to the fragmentation of the global trade regime with different rules for different regions (Dollar, 2020). The rules being applied to RTAs could adversely impact the relevance of MTS and lead to power-based trade regimes, in turn hampering the WTO’s capacity as a global trade arbiter (Baldwin, 2014).

Nevertheless, the number of RTAs has grown over the years (WTO, RTA-IS) and these pacts have now become an integral component of the global trade architecture. They have also contributed

to innovations in the trading system, including ways to address new issues such as those related to the digital economy (Duval and Mengjing, 2017).

Against this background, it has become imperative to analyze them particularly from a perspective of identifying provisions in them that have the potential to be multilateralized as well as formulating a mechanism for the same. In this context, it is also vital to compare such an analysis with the lessons learnt from the Tokyo Round Codes that were multilateralized as well as the expansion of plurilaterals such as the Information Technology Agreement. It needs to be underlined that multilateralization of some of the concepts adopted in the regional arrangements would require internalization of elements of S&DT to enhance their acceptability by the developing world over time.

Such an exercise to multilateralize certain provisions of RTAs can also help address the criticism of the “proliferation” of RTAs leading to “overlapping rules” and “spaghetti bowl of rules of

origin”, in turn increasing costs of production and trade as well as hampering the Global Value Chain concept of “fragmentation of production”. Multilateralization of RTA provisions through harmonization of rules could also help reduce trade conflicts and in the process strengthen multilateralism and global trade governance through the WTO (for details, refer Estevadeordal,

et al., Eds, 2009; Baldwin, et al., 2009; Baldwin and Low, Eds, 2009).

The G20 could step in here and provide the means and resources for a thorough analysis of the potential transition path from regional to multilateral agreements. The G20 Trade, Industry and Investment Working Group could, however, suggest the areas within RTAs that have the potential to be multilateralized following an analysis. It is not necessary to build up new research capacities. What is needed, of course, is a process to commission research efficiently and effectively as well as funding.

2 (b): Analysis of select multilateral organizations to understand the multiplicity of flows and thoughts of their members, with a view to ensure greater effectiveness of the WTO

In a similar vein, the G20 should initiate a comparative analysis of other multilateral organizations/entities such as the United Nations (UN), IMF, World Bank, the World Health Organization, the International Labor Organization and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Like the WTO, other similarly placed multilateral organizations too have faced challenges relating to decision-making by consensus. They have also been troubled by the abuse of veto power and control of power by some geo-politically and geo-economically influential member states as well as marginalization of weaker states in terms of their representation and voice in the decision-making processes. In this context, it is essential to understand the broad canvas of decision-making in multilateral organizations to see if the WTO processes can gain from any inclusive and equitable mechanisms that have evolved elsewhere, including during crisis situations, to break stalemates through effective and innovative decision-making strategies.

Such a multi-dimensional analysis of similarly placed multilateral bodies is meant to understand the multiplicity of flows and thoughts of their members, in order to detect mechanisms to mainstream various economic, social and political realities in the decision-making exercise in a manner that will enhance the resilience, sustainability and effectiveness of the WTO. Special focus should be given to understanding the nature of influence of vulnerable economies as well as developing country-coalitions in multilateral agenda-setting, negotiation processes as well as the final outcomes.

This kind of a study can also help members in facilitating mechanisms that enable WTO reforms through effective inter-linkages with other multilateral organizations, especially in the light of the

global risks such as pandemics and climate change and those related to geo-politics.

3: Taking first steps to revitalize the Dispute Settlement Mechanism of the WTO

The current paralysis of the WTO’s AB highlights the urgency of WTO reform for well-functioning MTS. The DSM, including the AB, has provided much-needed security and predictability to the

MTS. Our proposal is directed toward the general principles of the DSM, but also acknowledges details as suggested under various proposals including those for amendment of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU) (See Table 1 in the Appendix).

We propose that the AB deadlock should be seen within a larger context that requires addressing long-standing issues, particularly with respect to developing countries. Gonzáles and Jung

(2020) argue that the leading developing countries could claim to retain S&DT as a starting point of the give-and-take negotiation process to preserve and improve the WTO’s appeals process. Technical assistance and capacity-building support are also essential as they are aimed at addressing the capacity gap between developed and developing countries, especially to deal with the lengthy and costly dispute settlement procedures which need to be reformed. Members with better legal capacity, usually from the developed world, are currently better placed to win disputes.

The WTO has been challenged by its inadequate resources in keeping up with the growing workload, the intricacies of the disputes as well as the legal arguments therein (Van den Bossche, 2022). Moreover, nations are increasingly resorting to litigation to win trade disputes, rather than settling them through negotiations—an issue that highlights the growing disparity between the judicial and negotiating branch of the WTO.

A weakened DSM is leading to doubts about the WTO’s effectiveness and reliability as a global body governing international trade, and therefore, heightens the need for its reforms. Some of the DSM reform proposals (See Table 1 in the Appendix) can be suitably adopted to address several concerns of the membership. G20 itself has acknowledged the need for such amendments in its meeting in 2019. Hence it needs to take that intent aggressively forward for materialization.

Concluding Remarks

The G20 as a dominant economic and political power grouping has a duty to drive the WTO reforms in an inclusive, transparent and equitable manner (Footnote 2). The above-mentioned proposals, including those concerning the DSM, can be taken forward through the following steps:

(i) As the current President of the G20, Indonesia needs to take the lead in rolling out these proposals by including them in the agenda of the Trade, Industry and Investment Working Group and highlighting that the topic of WTO reforms has been under discussion in the G20 for a long time (Footnote 3). Indonesia should aim to ensure that the G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration prioritizes the need for expeditious reforms of the WTO.

(ii) Following the conclusion of the G20 Indonesia meeting, the G20 members should start gathering support for WTO reforms through their respective regional trade, economic and political associations. In the talks with the regional blocs, the G20 members should convey the importance of reforming the WTO by eliminating outdated rules and processes as well as the long-standing imbalances/asymmetries between the developing and developed countries. By taking forward the previous Saudi Arabia and Italy G20 WTO reform efforts (Footnote 4), G20 members can help drive these reforms through a pledge to de-escalate recent trade tensions and prevent unilateral actions and discriminatory trade policies. Such a move would help bring about certainty in regulations, fix supply chain issues, and in turn boost investor confidence and business climate to strengthen growth, ultimately leading to “reglobalization” (Swanson, 2021).

Further, our proposal emphasizes incorporation of adequate flexibilities in WTO agreements on the basis of effective S&DT provisions to allow countries to ground their reform commitments

on their national capacities (Footnote 5). Such constructive approaches would also allow members to voluntarily engage in plurilaterals/JSIs using “the principle of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and capabilities” and be open to being subjected to healthy peer pressure.

Finally, these proposals are aimed at ensuring that open, transparent and non-discriminatory trade negotiations through inclusive and equitable processes happen within the WTO ambit itself and not outside. Ensuring the centrality of the MTS can help map out concrete actions to support the global economic recovery in the near-term and address evolving trade issues in the post pandemic era (Footnote 6).

References

Anabel González and Euijin Jung, Developing Countries Can Help Restore the WTO’s Dispute Settlement System (Policy Brief 20-1), Peterson Institute for International Economics. January 2020.

https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/developing-countries-can-help-restore-wtos-disputesettlement-system

Ana Swanson, W.T.O. chief calls for deeper global trade to address supply chain disruptions, The New York Times, 21 March 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/21/business/world-tradeorganization-supply-chains.html

Antoni Estevadeordal, Kati Suominen, and Robert Teh, eds. Regional rules in the global trading system. Cambridge University Press, 2009. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/region_rules09_e.pdf

Congressional Research Service – Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs and Rachel F. Fefer, ‘World Trade Organization: Overview and Future Direction’, (R45417), 18 October, 2021. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R45417.pdf

David Dollar, The future of global supply chains: What are the implications for international trade, Reimagining the global economy, Brookings Institute, 17 November, 2020.

https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-future-of-global-supply-chains-what-are-the-implications-forinternational-trade/

G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Meeting: Communiqué, G20 Information Centre – University of Toronto, September 22, 2020. https://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2020/2020-g20-trade-0922.html

Geneva Trade Platform’s website on WTO Plurilaterals https://wtoplurilaterals.info/ G20 (2021), G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration, G20 Italia 2021 https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/7_G20%20Rome%20Leaders%27%20Declaration.pdf

Jo-Ann Crawford and Roberto V. Fiorentino, The Changing Landscape of Regional Trade Agreements, Discussion Paper No: 8), World Trade Organization, 2005.

https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/discussion_papers8_e.pdf

Mehmet Sait Akman, Axel Berger, Fabrizio Botti, Peter Draper, Andreas Freytag, Claudi Schmucker, Boosting G20 Cooperation for WTO Reform: Leveraging the Full Potential of Plurilateral

Initiatives, G20 Insights Policy Brief, 25 September 2021.

Peter Van den Bossche, Is there a Future for the WTO Appellate Body and WTO Dispute Settlement?. WTI Working Paper No. 01/2022. Available at https://www.wti.org/research/publications/1344/is-there-a-future-for-the-wto-appellate-body-and-wtodispute-settlement/

Richard Baldwin, and Patrick Low, eds., Multilateralizing regionalism: challenges for the global trading system. Cambridge University Press, 2009. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/multila_region_e.pdf

Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett, and Patrick Low, “Beyond tariffs: multilateralising deeper RTA commitments.” 79-141, 2009. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/con_sep07_e/baldwin_evenett_low_e.pdf

Richard Baldwin, WTO 2.0: Governance of 21st century trade. The Review of International Organizations, Springer, vol. 9(2), pages 261-283, June, 2014. https://ideas.repec.org/a/spr/revint/v9y2014i2p261-283.html

The Economist (2019), The Steam has Gone out of Globalisation, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/01/24/the-steam-has-gone-out-of-globalisation.

WTO website, Why work at the WTO? https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/vacan_e/whywto_e.htm

World Trade Organization (2021a), ‘The legal status of ‘joint statement initiatives’ and their negotiated outcomes’, (WT/GC/W/819), 19 February 2021. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/GC/W819.pdf&Open=True

World Trade Organization (2021b), Trade policy review – Report by the Secretariat – The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, WT/TPR/S/407, 27 January 2021. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/s407_e.pdf

WTO, Regional Trade Agreements Information System (RTA-IS) https://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx

WTO, Strengthening and modernizing the wto: discussion paper – Communication from Canada,

JOB/GC/201, 24 September 2018. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspx language=E&CatalogueIdList=248327&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=0&FullTextHash=371857150 &HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True

WTO, Joint Communiqué of the Ottawa Ministerial on WTO Reform, 26 October, 2018. https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news18_e/dgra_26oct18_e.pdf

WTO, Communication from the European Union, China, Canada, India, Norway, New Zealand, Switzerland, Australia, Republic of Korea, Iceland, Singapore and Mexico to the General Council,

WT/GC/W/752, 26 November, 2018. https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009DP.aspxlanguage=E&CatalogueIdList=249918&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=0&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=True&HasSpanishRecord=True#:~:text=It%20is%20proposed%20to%20amend,of%20the%2090%2Dday%20timeframe.

WTO, Communication from the European Union, China and India to the General Council, WT/GC/W/753, 26 November, 2018. https://docsonline.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S009-DP.aspxlanguage=E&CatalogueIdList=249937,249918,249919,249678,249534,249527,249457,249426,249402,249403&CurrentCatalogueIdIndex=2&FullTextHash=371857150&HasEnglishRecord=True&HasFrenchRecord=False&HasSpanishRecord=False#:~:text=It%20is%20proposed%20to%20provide,%2FGC%2FW%2F752%20.

Yann Duval and Kong Mengjing, Digital trade facilitation: Paperless trade in regional trade agreements, ADBI Working Paper Series No: 747), Asian Development Bank Institute, June 2017.

https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/321851/adbi-wp747.pdf

Footnote

1: This is a term first coined by The Economist (2019), referring to a pattern showing the slowing advancement of globalization following the end of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

2: The G20 has been reiterating its political support for WTO reforms over the years. The SaudivArabia Presidency saw the launch of the Riyadh Initiative “on the Future of the WTO, which aimsvto identify common ground and shared principles for the next 25 years of the WTO” (WTO, 2021b). The G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration (G20, 2021) also emphasizes G20’s continued efforts to play an essential role in providing political support for WTO reform discussions. Indonesia’s Presidency of the G20, therefore, offers a crucial opportunity to take forward this legacy issue and discuss reform measures more concretely to take them to their logical conclusion.

3: Several points in the G20 Trade and Investment Ministerial Meeting communiqué of 2020 refer to the G20’s acknowledgement of the need for the WTO reforms and its commitment to facilitate

the same (G20, 2020).

4: The Riyadh Initiative on the Future of the WTO in the G20 Saudi Arabia and its reaffirmation in the G20 Rome Leaders’ Declaration.

5: We recommend a multidimensional approach so that the concerns of member countries that fall under various levels of development are taken into consideration.

6: Making the MTS more effective through WTO reforms is important to address the challenges of ensuring broad-based recovery from the ongoing crises. While the WTO reform agenda is expected to figure prominently in this year’s G20 meetings, the members of the grouping need to show greater willingness by mobilizing the needed political will to set the direction and scope of the reform process.