Financial stability is a prerequisite for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement. A value-driven and rules-based Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) that fosters cooperative policy sovereignty toward these goals needs to be at the center of Group of Twenty (G20) policymaking. The G20 has long supported “further efforts to strengthen the [GFSN] and promote a resilient international monetary and financial system, including by reconsidering elements of the IMF’s lending toolkit and deepening collaboration with regional financing arrangements (RFAs).” To this end, we recommend urgent action. The G20 must expand and bolster the GFSN’s geographic coverage as well as the range of instruments to identify, prevent, and mitigate crises. It must expand the thematic coverage of the GFSN to monitor volatile capital flows, pandemics, and climate shocks. A stepwise, quota-based increase in resources for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an expansion in the level and role of Special Drawing Rights (SDR), and new resources for new and existing RFAs will be critical to this expansion. This renewed multilateralism will enable nation-states to pursue their own strategies to meet these broader goals in a globally coordinated matter.

Challenge

During a period when support for multilateral institutions has been waning, the world economy continues to face significant financial fragility due to global policy tensions, volatile capital flows, the COVID-19 pandemic, and climate shocks. As fragility has increased, so has the overall size of the global financial system and debt levels. The financial agents involved and the type of financial transactions and assets, including digital financial assets, have also changed, generating new risks. However, the capacity of national, regional, and global institutions to keep pace with these trends has been on the decline. A major challenge for the Group of Twenty (G20) nations is to build a comprehensive GFSN that can identify early signs of financial fragility, prevent fragility from doing harm and spreading, and provide ample liquidity when nations experience balance of payments problems and crises. A patchwork GFSN has emerged over the past two decades, but it has proven to be limited in its ability to identify, prevent, and mitigate financial instability across the world.

Proposal

The G20 and the IMF have repeatedly reaffirmed their “commitment to a strong, quota-based, and adequately resourced IMF” to preserve its role at the center of the GFSN. They have also advocated for “further efforts to strengthen the [GFSN] and promote a resilient international monetary and financial system, including by reconsidering elements of the IMF’s lending toolkit and deepening collaboration with regional financing arrangements” (G20 2019; IMFC 2019).

To this end, we propose that the G20 call on member governments and the broader global community to reform and expand the GFSN’s geographic and thematic coverage, toolkits and instruments, financial resources, and governance and coordination functions. The costs of inaction are proving to be significant. It is paramount that the G20 jump-start a process to put in place a comprehensive, robust, and multilayered GFSN that strikes a balance between coordination and autonomy.

The Limits of the GFSN

The GFSN has not evolved by design, but rather as a patchwork of institutions and instruments, several of which have arisen in response to the unmet needs of the system. A well-functioning GFSN would need a coordinated set of engagements that can identify financial instability and risk (commonly referred to as surveillance), precautionary instruments, and facilities to mitigate financial instability when it arises.

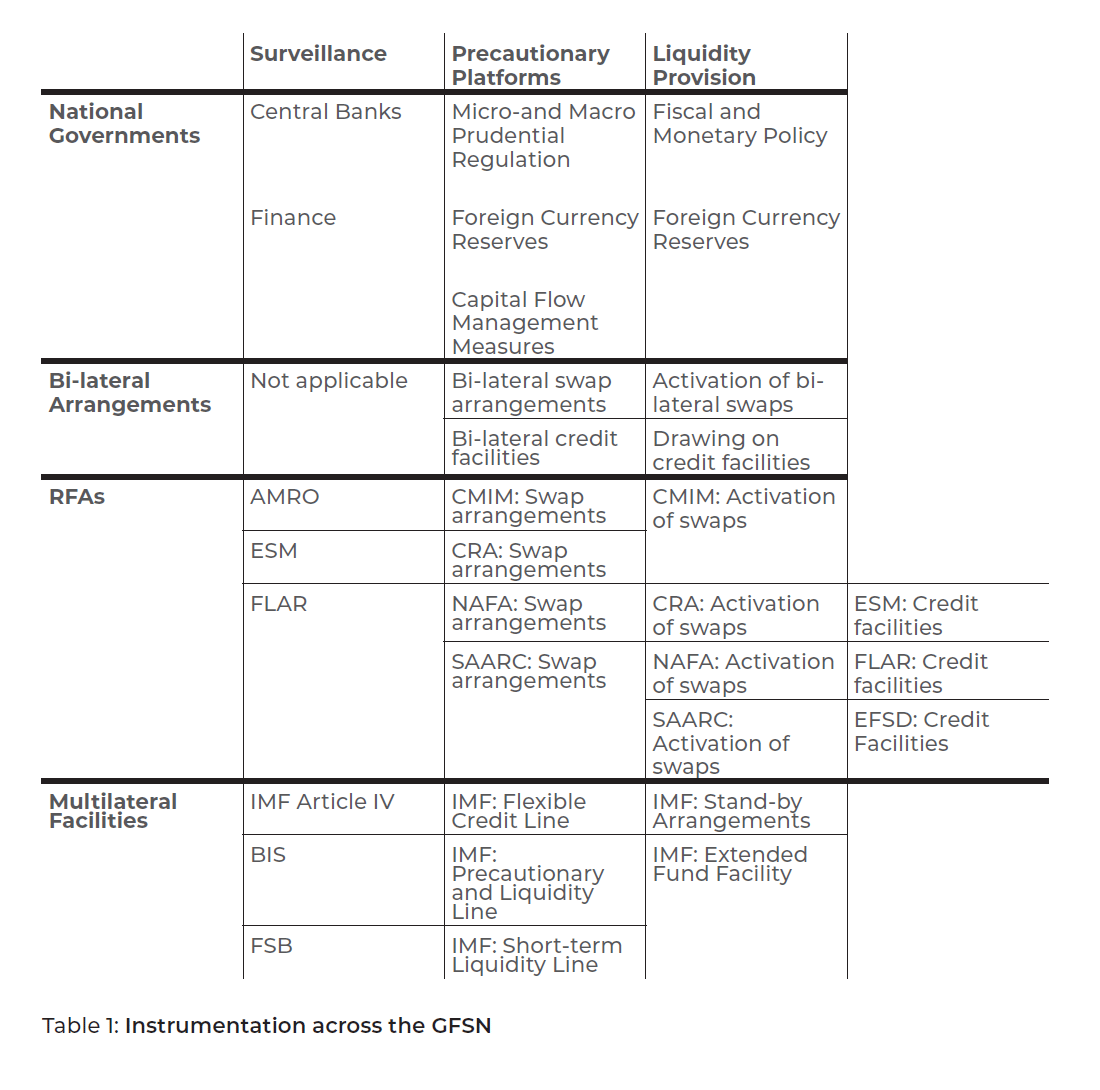

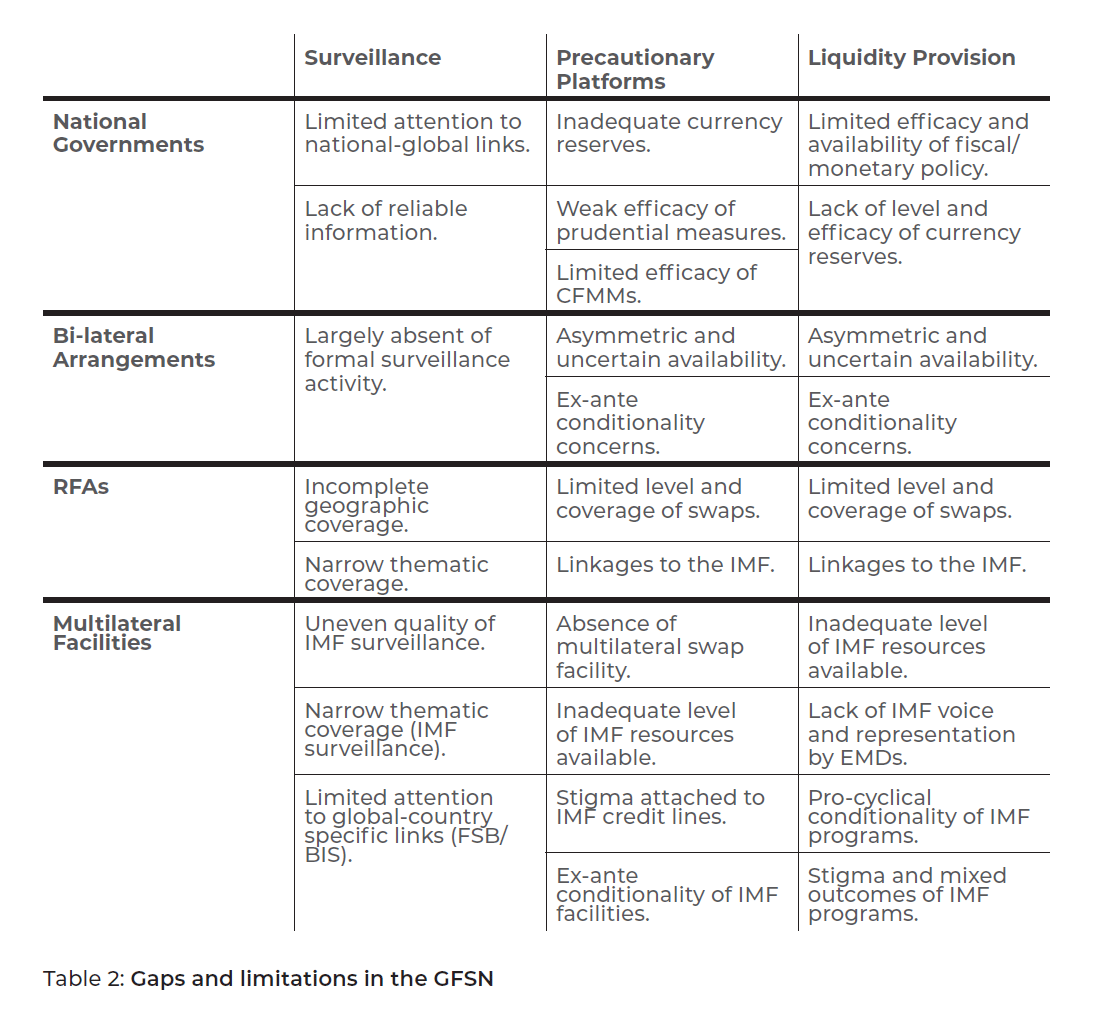

These functions are performed across four layers of the global system. Table 1 provides an illustrative list of the four layers of the GFSN and the major instruments used across the spectrum. Table 2 exhibits some of the gaps and limitations in the system.

Acronyms: ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), Chang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM), Arab Monetary Fund (ArMF), European Stability Mechanism (ESM), Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), North American Framework Agreement (NAFA), Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR), South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development (EFSD).

The first layer of the GFSN is the realm of national governments and central banks that provide their own surveillance, precautionary measures, and contingency policies. As the major source of financial instability comes in the form of external shocks related to volatile capital flows, climate change, and now pandemics, national-level surveillance is sufficient by itself to identify sources of fragility that will impact their economies. Beginning in the 1990s, after controversial crises and IMF responses in East Asia, many countries now self-insure their economies by accumulating foreign exchange reserves and use capital flow management measures (CFMMs) and macroprudential policies to prevent and mitigate crises at a national level (Ghosh et al. 2012; Gallagher 2015; Ocampo 2017). These policies can have positive results and provide nations the most autonomy for preventing and mitigating crises, but research has demonstrated that their effectiveness can diminish over time for a variety of reasons. Furthermore, by purchasing developed countries’ assets, this insurance strategy amounts to an enormous transfer of wealth from emerging markets and developing economies to more advanced economies at a high opportunity cost to domestic investment (Ocampo 2017).

Certain nations also have access to bilateral credit lines and swaps. The United States Treasury is home to the Exchange Stabilization Fund that disbursed numerous loans and swaps to Mexico in the 1990s. Japan and Russia also provided bilateral credit to neighboring countries during the same period (Henning 1999; Katada 2001; Grimes 2009; Schneider and Tobin 2019). Somewhat unique to the recent financial crises has been a network of central banks that provides bilateral swaps to some countries during a crisis, which performs the second layer of credit lines and swaps (Mehrling 2015). The crisis of 2008–09 and the succeeding eurozone crisis led to a significant use of these swap lines with no ex-post conditionality. Additionally, since 2008, the People’s Bank of China has signed numerous swap agreements with other countries. Rather than the hegemonic provision of public goods, many countries are concerned that the allocation of bilateral swaps is uncertain, incomplete, and asymmetric. Many countries were concerned that they did not have access to this type of support—either because they did not qualify because of ex-ante conditionality criteria or more arbitrary geopolitical criteria (Aizenman and Pasricha 2010; Volz 2016; Ocampo 2017).

The joint announcement in March 2020 by the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, and the Swiss National Bank to enhance the provision of liquidity amongst each other via the standing USD liquidity swap line arrangements is an important contribution to the management of the crisis. However, it also illustrates that the vast majority of economies are excluded from these lines of defense.

The third layer of support is in the form of RFAs that take the form of swap arrangements (such as the Chang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement) and credit facilities (such as the Latin American Reserve Fund, the European Stability Mechanism, and the Arab Monetary Fund). While RFAs are more flexible and have more ownership over their policies, they lack adequate levels of capital, and those that require a parallel IMF program are not sufficiently used because of the general stigma associated with IMF conditionality (McKay et al. 2011). Thus, except for the eurozone’s extensive use of the ESM and some countries’ use of the FLAR (which has no formal conditionality), the other RFAs remained dormant during the recent crisis in favor of swaps or self-insurance (Kring and Grimes 2019). Although many of the RFAs, especially the CMIM (through AMRO) and FLAR, have developed sophisticated surveillance activities that are more attuned to understanding how capital flows impact regional stability, their limited mandates, size, and capacity have prevented them from expanding their purview to examine new shocks associated with climate change and health pandemics. Furthermore, a large number of countries across the world lack any access to an RFA (Volz 2016; Mühlich and Fritz 2018).

Most nations have to resort to the fourth and only multilateral layer, the IMF. IMF surveillance efforts have been assessed by the IMF Independent Evaluation Office to be lacking as they have failed to anticipate the instabilities preceding the financial crisis of 2008–09 (IEO 2014; IEO 2019). This was strengthened after the crisis, both at the bilateral level and through the creation of a range of multilateral surveillance instruments. Only recently has the IMF focused on global climate change and health pandemics, with landmark issues of the Fiscal Monitor and the Global Financial Stability Report that have included climate change (IMF 2019a, 2019b). However, the IMF is only now starting to officially incorporate these important sources of financial shocks into their analyses of the financial systems of member countries.

Additionally, the limitations of existing facilities limit the Fund’s ability to perform effectively. In particular, between 2009 and 2010, the Fund created a host of precautionary facilities that were potentially more flexible, including the Flexible Credit Line (FCL) and the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL). These new facilities received little use because of the inherent stigmas attached to IMF programs and the strict ex-ante conditions involved in qualifying for them (Marino and Volz 2012). Thus, nations often had no choice but to resort to traditional Stand-By Arrangements that remain highly conditional, frequently include contractionary macroeconomic policies, and have a mixed record in the context of crisis recovery and social outcomes (Kentikelenis et al. 2016).

There are also significant concerns about voice and representation of all members of the IMF and delays to regular quota reviews (Gao and Gallagher 2019). It took six years for the 2010 quota increases and redistributions of votes at the IMF to be adopted. Further, it is quite troublesome that expected efforts to follow-up with new reforms on quotas and votes have been delayed until 2023. Although the IMF is tasked to follow a “doctrine of economic neutrality” (Swedberg 1986), case studies and statistical analyses have found that lending decisions (including loan conditionality) often reflected the geopolitical and economic interests of G7 countries in general and the US in particular. Considering the IMF, Thacker (1999), Stone (2002, 2011), and Copelovitch (2010a, 2010b) find this pattern, whether looking at countries known to be important to the US at the time or when analyzing key United Nations General Assembly votes. Dreher et al. (2009a, 2010, 2015) demonstrated that this favoritism extends to IMF lending, and Dreher et al. (2018) linked this specifically to UN Security Council voting records.

Proposals for Expansion and Reform of the GFSN

To reiterate, the G20 and IMF have called on members and beyond to strengthen the GFSN and “promote a resilient international monetary and financial system, including by reconsidering elements of the IMF’s lending toolkit and deepening collaboration with regional financing arrangements.” (G20 2019; IMFC 2019). To this end, this policy brief advances a five-point policy agenda to address the shortcomings of the present state of the GFSN:

Expand the available resources of the GFSN.

We encourage the G20 to call on member states to provide significant new resources for new swap facilities, the IMF, and the RFAs. As indicated above, the GFSN is not keeping pace with the magnitude of the global financial system. Not counting swap arrangements, the size of the GFSN in terms of core capital is roughly USD 13 trillion, including global currency reserves—just 4 percent of total global financial assets as measured by the Financial Stability Board (FSB 2020). Quota-based increases should form the core of IMF resource mobilization, and the 16th Quota Review should be adopted as soon as possible, and mandate a stepwise increase in quota increases, and a redistribution of quota and voting shares. Existing and newly created RFAs should be scaled up in a stepwise manner as well.

As a stop-gap, it is of vital importance to ensure that the IMF’s current lending capacity is maintained. Although the ongoing agreements on renewal and expansion of “Bilateral Loans and Note Purchase Agreements” and the “New Arrangements to Borrow” (NAB) are important, they should never be seen as a substitute for an adequate level of quotas. More ambitiously, however, creative alternatives should be considered such as broadening the role and use of SDRs as an instrument of international policy cooperation, and in this regard to its more active use as a reserve currency and source of financing of IMF programs, which requires sizable and more frequent SDR allocations (G-24 2018; Ocampo 2017). The IMF board should approve an allocation of SDRs of at least USD 500 billion (Gallagher et al. 2020a, 2020b). Close to two-fifths of such an allocation would enhance the international liquidity of emerging and developing economies, which are the primary users of SDRs. A decision should also be adopted by which high-income countries would lend the SDRs they do not use to the IMF, to enhance the Fund’s lending capacity.

Expand the geographic coverage of the GFSN.

We encourage the G20 to call on the IMF to establish a multilateral swap facility and to call for and support the development of RFAs to broaden the geographic coverage of the GFSN. Many countries lack access to a variety of swap and credit lines at the regional and multilateral levels. In response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve took immediate action, first to lower the funding cost of its swap lines signed with five other central banks, and then extended the dollar swap lines to nine more central banks to meet the surge for dollar liquidity. Such emergency assistance would certainly help lessen strains in the global dollar funding market for some specific jurisdictions. However, it benefits only two emerging economies (Brazil and Mexico). In the immediate term, the swap lines of the Federal Reserve should be extended to at least the People’s Bank of China. As proposed below, a multilateral, short-term liquidity facility should also be established for all nations. The most glaring gap in RFAs is in Africa. Although several African countries have signed on to a new African Monetary Fund, many countries are yet to sign on, and they then need to ratify the articles of agreement (Dagah et al. 2019). Significant gaps also exist in South and Central America and the Caribbean, Eurasia, and South Asia. Also, and notably, several G20 countries—Argentina, Brazil, South Africa, and Turkey—are not covered by an RFA.

Expand the thematic coverage of the GFSN.

We encourage the G20 to call on GFSN institutions to expand their surveillance activities to focus on the new drivers of shocks, particularly the spillovers generated by the monetary policies of advanced countries, volatile short-term capital flows, cross-border digital asset movements, global climate change, and health epidemics. In particular, it is necessary to highlight the importance of the surveillance of macroeconomic and financial conditions that generate the risk of crises. Another glaring gap in the system is the lack of an adequate sovereign debt workout arrangement that involves private creditors, which is urgently required given the current rising levels of debt and the prevalence of shocks in the world economy. In relation to official debt workouts, the Paris Club must expand the 2020 debt standstill for LICs into 2021, private creditors participate in this process as requested by the G20, and other large creditor countries, notably China, engage in similar debt relief efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

Expand the toolkit of the GFSN.

We encourage the G20 to call on its members to expand the set of tools available across the GFSN. First, a multilateral Short-term-Liquidity Swap (SLS)—a Fast Qualification Facility—is necessary that would multilateralize central bank swaps or create a new IMF swap arrangement financed by the automatic emission of new SDRs to tackle sudden capital flow blockages. This has been elaborated on by IMF staff, and earlier versions have been proposed by experts and the G20 Eminent Persons Group (Truman 2010; IMF 2017a; De Gregorio et al. 2018). In 2017, the proposal for such a facility was rejected by the IMF Board by a minority of creditor shareholders that have a disproportionate share of voting rights at the IMF, but it is shovel ready in design. It is also important to improve the access and flexibility of existing tools, such as the FCL and the PLL for tackling potential balance of payments pressures. Even more importantly, access and funding for the emergency facilities—the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) and the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF)—must be improved further to face the urgent needs arising from pandemics, commodity price shocks, conflict situations, climate change, and natural disasters. The recent IMF decision of double access to these emergency facilities temporarily represents a good start.

Most importantly, the IMF, RFAs, and national entities need to align conditionality policies with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Despite the recognized improvements in the number of conditionalities explicitly required in IMF programs, in addition to spending “floors” for social programs, IMF conditionalities still carry a stigma because of their pro-cyclical nature and social impact. While the academic literature on the impact of IMF programs on economic growth is somewhat mixed, there is overwhelming evidence that IMF conditionality is correlated with worsening inequality, educational spending, health systems, and environmental quality (IMF 2018; Kentikelenis et al. 2016).

Expand coordination and governance of the GFSN and the policy space of its members.

We encourage the G20 to call on the IMF and other parts of the GFSN to reform its governance structures and cooperate in a manner that provides global public goods without jeopardizing national policy sovereignty. The IMF, with its broad membership, remains the global multilateral body that provides predictability to liquidity needs in the global economy. Echoing G20 principles, the IMF should work with central banks and RFAs in a manner that respects the roles, independence, and decision-making processes of each institution, taking into account regional specificities in a flexible manner (G20 2011; McKay et al. 2011; Volz 2013; EPG 2018). These institutions should closely cooperate during crises while allowing for complementarity and diverse approaches to governance, surveillance, program design, and conditionality over the longer run. The new multilateral liquidity swap line we propose would be a good example of strengthening the cooperation among members of the GFSN. They should create mechanisms for greater international policy coordination for managing capital flows across regions and between emerging markets and developing countries and advanced economies (Ostry et al. 2012). Moreover, the IMF should work to ensure that trade and investment regimes also allow ample policy space for national efforts and international cooperation on capital flow management. Such treaties increasingly restrict the ability of such coordination, and the IMF has recognized that “these agreements in many cases do not provide appropriate safeguards or proper sequencing of liberalization, and could thus benefit from reform to include these protections” (IMF 2012, 8; Gallagher et al. 2019).

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Aizenman, Joshua, and Gurnain Kaur Pasricha. 2010. “Selective Swap Arrangements

and the Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Interpretation.” International Review of

Economics & Finance 19 (3): 353–65.

Copelovitch, Mark S. 2010a. “Master or Servant? Common Agency and the Political

Economy of IMF Lending.” International Studies Quarterly 54 (1): 49–77.

Copelovitch, Mark S. 2010b. The International Monetary Fund in the Global Economy:

Banks, Bonds, and Bailouts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dagah, Hadiza, William Kring, and Daniel Bradlow. 2019. “Jump-starting the African

Monetary Fund.” GEGI Policy Brief No. 008. Boston, MA: Global Development Policy

Center, Boston University.

De Gregorio, José, Barry Eichengreen, Takatoshi Ito, and Charles Wyplosz. 2018. IMF

Reform: The Unfinished Agenda. Geneva Reports on the World Economy. Geneva:

International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies and the Centre for Economic

Policy Research.

Dreher Axel, Valentin F. Lang, B. Peter Rosendorff, and James Raymond Vreeland.

2018. “Buying Votes and International Organizations: The Dirty Work-Hypothesis.”

CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13290. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Dreher, Axel, Jan-Egbert Sturm, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2009a. “Global Horse

Trading: IMF Loans for Votes in the United Nations Security Council.” European

Economic Review 53 (7): 742–57.

Dreher, Axel, Jan-Egbert Sturm, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2009b. “Development

Aid and International Politics: Does Membership on the UN Security Council Influence

World Bank Decisions?” Journal of Development Economics 88 (1): 1–18.

Dreher, Axel, Jan-Egbert Sturm, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2010. “Does

Membership on the UN Security Council Influence IMF Conditionality?” CEGE

Discussion Paper No. 104. Göttingen: Center for European, Governance and

Development Research, Georg-August University Göttingen.

Dreher, Axel, Jan-Egbert Sturm, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2015. “Politics and

IMF Conditionality.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 5(1): 120–48.

FSB. 2020. “Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2018.”

Basel: Financial Stability Board.

Gallagher, Kevin P. 2015. Ruling Capital: Emerging Markets and the Reregulation of

Cross-border Financial Flows. Ithaca, NY: Cornel University Press.

Gallagher, Kevin P., Sarah Sklar, and Rachel Thrasher. 2019. “Policy Space for

Managing Capital Flows in Trade and Investment Treaties: An Empirical Approach.”

G-24 Working Paper, Washington, G-24 Secretariat.

Gallagher, Kevin P., José Antonio Ocampo, and Ulrich Volz. 2020a. “It’s Time for a

Major Issuance of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights.” Financial Times Alphaville,

March 20, 2020. https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2020/03/20/1584709367000/It-s-time-fora-major-issuance-of-the-IMF-s-Special-Drawing-Rights.

Gallagher, Kevin P., José Antonio Ocampo, and Ulrich Volz. 2020b. “Special Drawing

Rights: A Key Tool for Attacking a COVID-19 Financial Fallout in Developing Countries.”

Future Development, Brookings Institution, March 26, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/03/26/imf-special-drawing-rights-a-key-toolfor-attacking-a-covid-19-financial-fallout-in-developing-countries.

Gao, Haihong, and Kevin P. Gallagher. 2019. “Strengthening the International

Monetary Fund for Stability and Sustainable Development.” A Policy Brief submitted

to T20 Japan Taskforce, March 2019.

Ghosh, A. R., Ostry, J. D., and Tsangarides, C. 2012. “Shifting Motives: Explaining the

Buildup in Official Reserves in Emerging Markets since the 1980s.” IMF Working

Paper No. 12/34, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Grimes, William. 2009. Currency and Contest in East Asia: The Great Power Politics of

Financial Regionalism. Ithaca, Cornel University Press.

G20. 2019. G20 International Financial Architecture Working Group 2019 Final Report

to the Osaka Summit. G20 IFA, Japan. Accessed July 20, 2020. https://www.mof.go.jp/english/international_policy/convention/g20/annex4_1.pdf.

G-24. 2018. Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four on International Monetary

Affairs and Development. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Accessed

June 26, 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2018/04/20/intergovernmentalgroup-of-twenty-four-on-international-monetary-affairs-and-development.

Henning, C. Randall. 1999. “The Exchange Stabilization Fund: Slush Money or War

Chest Policy.” Analyses in International Economics No. 57. Washington, DC: Peterson

Institute for International Economics.

IEO. 2019. IMF Financial Surveillance. Washington, DC: Independent Evaluation

Office, International Monetary Fund.

IEO. 2014. IMF Response to the Financial and Economic Crisis. Washington, DC:

Independent Evaluation Office, International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2017. Adequacy of the Global Financial Safety Net—Considerations for Fund

Toolkit Reform. IMF Policy Paper. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2018. Structural Conditionality in IMF-Supported Programs—Evaluation Update.

Washington: International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2019a. Global Financial Stability Report, October 2019. Washington, DC:

International Monetary Fund.

IMF. 2019b. Fiscal Monitor, October 2019. Washington, DC: International Monetary

Fund.

IMFC. 2019. Communiqué of the Thirty-Ninth Meeting of the IMFC. Washington, DC:

International Monetary Fund. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/04/13/communique-of-the-thirty-ninth-meeting-of-the-imfc.

Katada, Saori. 2001. Banking on Stability: Japan and the Cross-Pacific Dynamics of

International Financial Crisis Management. East Lansing: University of Michigan

Press.

Kentikelenis, A., T. Stubbs, and L. King. 2016. “IMF Conditionality and Development

Policy Space, 1985–2014.” Review of International Political Economy 23 (4): 534–82.

Kring, William, and William Grimes. 2019. “Leaving the Nest: The Rise of Regional

Financial Arrangements and the Future of Global Governance.” Development and

Change 50 (1): 72–95.

Marino, Roberto, and Ulrich Volz. 2012. A Critical Review of the IMF’s Tools for Crisis

Prevention. DIE Discussion Paper No. 4/2012. Bonn: German Development Institute.

McKay, Julie, Ulrich Volz, and Regine Wölfinger. 2011. “Regional Financing

Arrangements and the Stability of the International Monetary System.” Journal of

Globalization and Development 2(1), Article 1.

Mehrling, Perry. 2015. “Discipline and Elasticity in the Global Swap Network.”

International Journal of Political Economy 44 (4): 311–24.

Mühlich, Larissa, and Barbara Fritz. 2018. “Safety for Whom? The Scattered Global

Financial Safety Net and the Role of Regional Financial Arrangements.” Open

Economies Review 29: 981–1001.

Ocampo, José Antonio. 2017. Resetting the International Monetary (Non) System.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Ostry et al. 2012. Multilateral Aspects of Managing the Capital Account. IMF Discussion

Note. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Schneider, Christina, and Jennifer Tobin. 2020. “The Political Economy of Bilateral

Bailouts.” International Organization 74 (1): 1–29.

Stone, Randall W. 2002. Lending Credibility: The International Monetary Fund and

the Post-Communist Transition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stone, Randall W. 2011. Controlling Institutions: International Organizations and the

Global Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swedberg, Richard. 1986. “The Doctrine of Economic Neutrality of the IMF and the

World Bank.” Journal of Peace Research 23 (4): 377–90.

Thacker, Strom. 1999. “The High Politics of IMF Lending.” World Politics 52 (1): 38–75.

Truman, Edward. 2010. The G-20 and International Financial Institution Governance.

Working Paper, No. 10-13. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International

Economics.

Volz, Ulrich. 2013. “Strengthening Cooperation between Regional Financing

Arrangements and the International Monetary Fund.” In Papers & Proceedings.

VII Conferencia Internacional de Estudios Económicos. Regionalismo financiero y

estabilidad macroeconómica edited by Carlos Andrés Giraldo, 8–17. Bogotá: Fondo

Latinoamericano de Reservas.

Volz, Ulrich. 2016. “Toward the Development of a Global Financial Safety Net or a

Segmentation of the Global Financial Architecture?” Journal of Emerging Market

Trade and Finance 52 (10): 2221–237.