The post-COVID stage represents a unique window of opportunity to accelerate the transition towards sustainable development. Public investment will be essential to achieve such a goal; yet, government spending in middleand low-income countries will address the myriad social demands arising from the current situation. Consequently, reinventing the incentive structure to catalyse efforts in mobilising private finance will remain more crucial than ever. The G20 should bring the debate to the next level and deliver a global public good: an internationally recognised standard for environmental, social and governance investment, key in allowing more effectively integrated approaches to public and private finance.

Challenge

The post-COVID stage will represent a unique window of opportunity to accelerate thus far timid transformations towards sustainable development. Public investment will be essential to achieve such a goal; yet, government spending in middleand low-income countries will address the myriad social demands arising from the current situation.

Consequently, reinventing the incentive structure to catalyse efforts in mobilising private finance will remain more crucial than ever. And one of the critical challenges for such endeavour is the lack of a common standard that allows for heightened sovereign demand to efficiently match the growing supply of environmental, social and governance (ESG) data tools informing sustainable investment decisions.

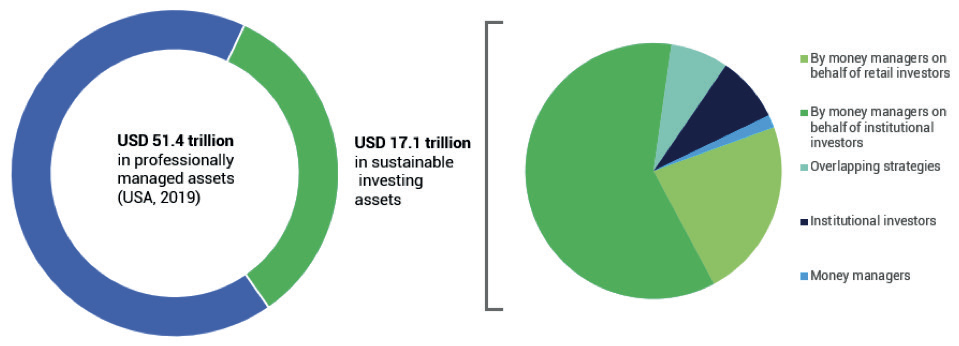

On GSIA/Bloomberg data, assets abiding by some form of ESG standard are on track to reach USD 55 trillion (up from USD 37.8 trillion by 2020EOY). Private investors consider ESG factors across USD 17.1 trillion of professionally managed assets in the US alone a 48 per cent increase since 2018.

Figure 1: Sustainable investment in the US (2019EOY)

Source: USSIF

Yet, despite such accelerated growth in sustainable funding, OECD data estimates that the existing gap in financing for developing countries towards achieving the 17 SDGs by 2030 still stands at USD 25 trillion through the next decade and expanding due to the COVID-19 economic contraction.

As policy makers and market authorities worldwide are accelerating ESG disclosure requirements for both corporates and investors, momentum is ripe for developing the most efficient and effective ways of both (1) evaluating the actual impact of sustainable financing; and (2) providing efficient policy tools for the unsupervised matching of demand and supply.

Their common baseline represents a critical asset to leverage: sovereignly defined SDGs and privately settled ESG standards show a high degree of convergence (an overlapping discernible in development finance institutions).

Both metrics provide insights into mostly intangible aspects of valuation such as corporate/sovereign reputation by measuring decisions taken by company management/governments that affect operational efficiency and future strategic directions of such entities.

However, whereas the international system has agreed upon a set of common goals and indicators crystalised in the 2030 Agenda, the proliferation of differing visions of what ESG means results in the misinterpretation of data (McFarlane, 2020).

With an estimated 185 multi-stakeholder initiatives in existence, and 59 classified as “standards” (UNDP/OECD, 2020), the levels of divergence between different ESG assessments of companies (upon which many investors rely) hold back the real impact of this ongoing global shift.

This proliferation of disclosure frameworks including but not limited to GRI, SASB, CDP, CTFD, DJSI and CHRB plus a growing number of rating agencies, investor surveys and performance standards represents an escalating concern.

And such discrepancies across ESG ratings affect company managers (BNP Paribas, 2019), who may feel less urgency to improve their ESG performance and identify appropriate strategies to do so.

Proposal

The need to develop a new “lingua franca”, a common framework that fosters public-private collaboration towards sustainability aligned with the Italian Presidency’s pillars and priorities stands chief among the priorities for the decade until 2030.

The G20 is furnished with the capacity to move the current discussion one step forward and deliver a specific global public good: an internationally recognised framework for environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment and comprehensive tools for its adoption and adaptation at the national level.

Several reasons cement our views on why the current setting is ripe for action:

1) The trend is well underway, and the setting provides the opportunity

The World Bank Investor Survey shows that 85 per cent of investors use ESG information to assess credit risk. One hundred fifty investors and 19 credit risk agencies signed on to the Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) Statement on ESG in Credit Risk and Ratings, which commits signatories to incorporate ESG in their credit analyses systematically and transparently (PRI, 2019).

As this trend unfolds, extensive work has been conducted on what needs to be done to harmonise ESG criteria and further align such standards with the SDGs. The most sophisticated effort was made by the OECD and UNDP, commissioned by the G7 ministers, to define a common framework focused on mobilising and enhancing the development impact of private finance through alignment with the SDGs.

Similarly, examples of stakeholders stating their willingness to coordinate are abundant. The GRI/SASB/CDP/CDSB/IIRC joint statement from September 2020, seeking to harmonise nonfinancial reporting, underpins our views about awareness and efforts undertaken in this regard.

2) But time is of the essence, as incentives for further dispersion are abundant

As different sides of the financial sector continue to demand data solutions, the spread keeps widening without clear disclosure rules, definitions or methodologies, increasingly contributing to misleading investors and market distortions.

Under the volatile setting resulting from the COVID-19 global disruption, such an increase in the availability of standards is bound to continue, further hampering the appropriateness of management and investment decisions relying upon increasingly scattered criteria.

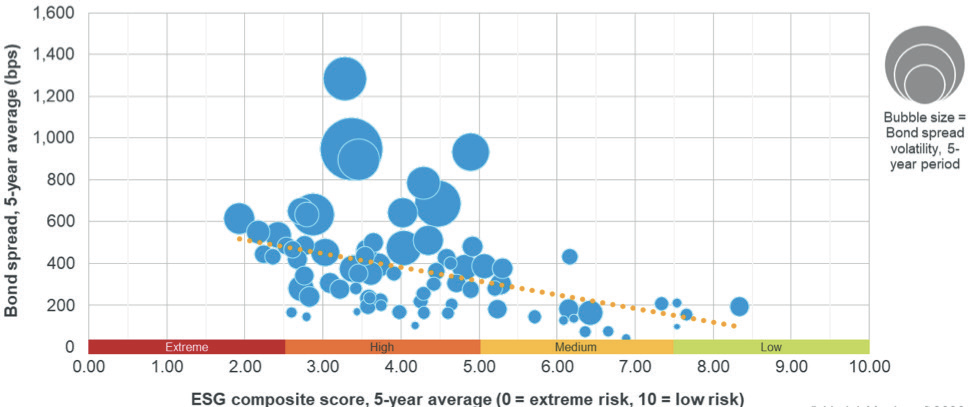

In the absence of this direct dialogue, such dispersion has critical consequences for both investors and developing economies. Investors may be unable to price in the country’s sustainability efforts correctly, with asymmetric information resulting in higher risk premiums, increased cost of borrowing for sovereign issuers, and deflated investment.

Hence, reducing the current level of dispersion setting global parameters that act as organising points could improve both the baseline of indicators used for such metrics and the quality of the evidence provided by the jurisdictions under assessment.

Figure 2: Average ESG risk scores, bond spreads and volatility for members of a standard emerging market bond portfolio, average from 2015 to 2019 Caption: Investment managers use ESG metrics to integrate political, climate and ESG risks into global macro strategies and use risk exposure to predicts sovereign bond pricing and volatility

Source: Verisk Maplecroft 2020

3) As before, the G20 can act to promote these changes

Unlike other international fora, the G20 strikes a unique balance of legitimacy and functionality to address these normative challenges. Gathering two-thirds of the world’s population and 80 per cent of its economy within a concise number of decision makers, the Group is equipped with a remarkable degree of legitimacy to harness discussions over the factual implementation of global standards.

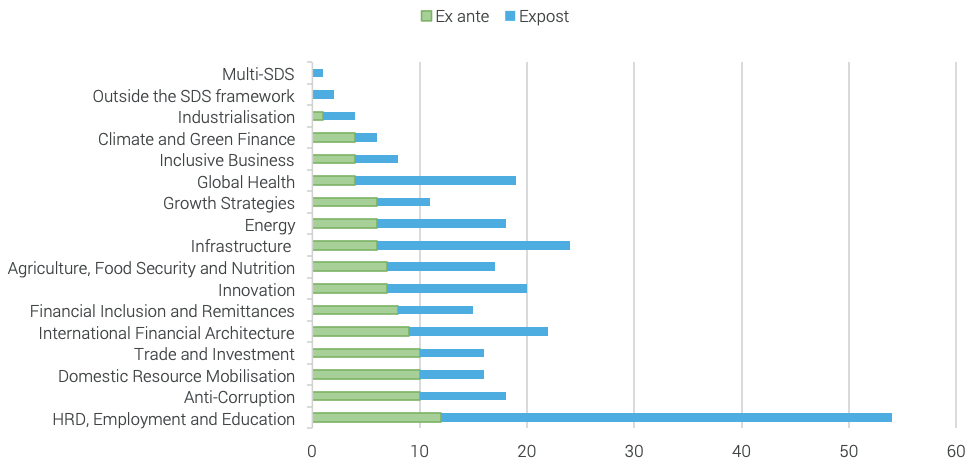

Figure 3: G20 collective actions in the Sustainable Development Sectors, after and before Action Plan on the 2030 Agenda (2010-2019)

Source: OECD

And as the Group has deepened its whole-of-G20 approach by improving collaboration across working groups, actions mandated by the G20 to support global goals are far from novel. Furthermore, they have remarkably increased in quantitative terms since adopting the G20’s 2030 Action Plan (see Figure 3 below).

4) The toolbox is open but something new is required

Agenda setting has been one of the G20’s primary modes to promote such collective action. By agreeing on common principles, initiating reforms and innovative collective instruments, it has leveraged the technical and administrative capabilities to fill gaps in international standard-setting before and it can do it again.

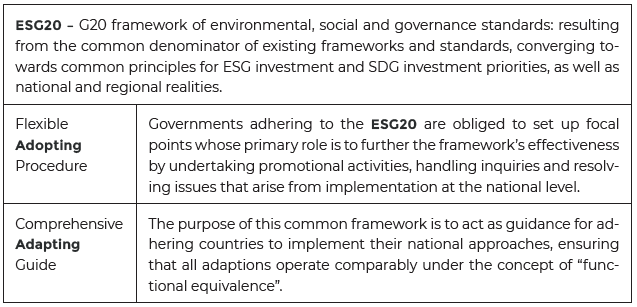

The dynamic reality of the discussions at hand risks creating yet another ESG framework, which is not what is needed. Hence, we propose to task the Sustainable Finance Working Group (SFWG) with the design of a global good: the G20’s Comprehensive Agreement on an ESG meta-framework (ESG20).

Tapping into the 2016 Principles for Global Investment Policymaking experience, the ESG20 framework of frameworks will have its core advantage in seeking to culminate ongoing harmonising efforts concerning ESG convergence, yet actively avoiding three major policy pitfalls:

i. Aiming for a “one-size-for-all”: The dual “adopting and adapting” process should provide enough wiggle room for sovereign accommodation to each domestic financial market.

ii. Well-intended but non-binding: Although any type of commitment over the IFESG would be voluntary, the active process of national “adapting and adopting” aims to ensure that such instruments become binding within each sovereign jurisdiction’s criteria.

iii. One-off effort: Adaptability and evolution of frameworks and composite indexes of sustainability remain essential (Bose, 2020) because the collective understanding of sustainability remains in flux.

Under such a notion, the agreement must include a revision mechanism to allow for bidirectional updates either driven by G20 or national focal points, based upon lessons from on-the-ground policy deployment.

5) The G20 can lead the charge in delivering such innovation as soon as possible

The urgency and scope of private capital mobilisation for the 2030 Agenda is now mission-critical. Given the diversity of context and stages of development, G20 efforts should aim for a globally oriented but domestically adaptable solution. By developing the proposed “ESG20” framework, cascading policy reforms would be country-specific, allowing each jurisdiction to effectively scale and streamline its own sustainable finance strategy yet allowing for “functional equivalence” as a way to provide clarity and equal footing.

The G20 has already acknowledged the critical role that finance plays in fostering the green transition and tackling climate change by establishing the Sustainable Finance Working Group. And the SFWG is already commanded with the task to identify and overcome barriers to a better alignment of the international financial system to the objectives of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement.

The political will to define a core set of variables would partially resolve inconsistencies and lack of uniform standards (López, Contreras and Bendix, 2020). Further, it would be in line with the decision made at the Second G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting (7 April 2021) and with the T20 policy recommendations to the G20 Finance Ministers (9 July 2021).

However, the development of the ESG20 is more than a technical suggestion of deploying a common yet differentiated set of converging standards for sustainable investment. It is a call to action to allow each country to recognise, support and adopt international standards and accelerate economic transformation in all sectors of the economy to help overcome global crises.

Hence, as a continuation of the political will mustered by the Italian Presidency in upgrading the status of the SFWG (from study to working group), initial efforts to find evidence-based and climate-focused roadmaps should be accelerated.

As a way of sustaining political momentum for such innovation, the creation process of this product should be monitored by a special political commission, led by the current presidency and co-led by the other two members of the “troika” (Saudi Arabia and Indonesia).

REFERENCES

Bloomberg Intelligence (2021), “ESG Assets May Hit $53 Trillion by 2025, a Third of Global AUM”, 23 February

BNP Paribas (2019), ESG Global Survey 2019: Investing with Purpose for Performance

Bose, Satyajit (2020), Evolution of ESG Reporting Frameworks, October, DOI:10.1007/ 978-3-030-55613-6_2

Bouyé, Eric; and Diane Menville (2021), “The Convergence of Sovereign Environmental, Social and Governance Ratings”, in World Bank Policy Research Working Papers, No. 9583 (March)

CFA Institute (2019), “Integrating ESG Factors into Sovereign Debt Analysis”, in Business Ethics, 4 November

Global Impact Investing Network (2020), 2020 Annual Impact Investor Survey, December

Lopez, Claude; Joseph Bendix; and Oscar Contretas (2020), “ESG Ratings: The Road Ahead”, in Milken Institute, 9 November

Blue Bay Asset Management, Verisk Ma plecroft (2019), ESG risk factors are material for sovereign debt investing, https://www.maplecroft.com/insights/analysis/esg-investing-sovereign-bonds-maplecroft-bluebay/

Verisk Maplecroft (2020), Is Conventional ESG Data Failing Mining Companies and investors?, https://www.maplecroft.com/insights/news-events/the-esg-data-challenge-for-investors-in-the-mining-sectorand-the-way-forward/

OECD + UNDP (2020) Framework for SDG Aligned Finance, https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/Framework-for-SDG-AlignedFinance-OECD-UNDP.pdf

OECD (2020), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021: A New Way to Invest for People and Planet, Paris, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3c30a9a-en

OECD/UNDP (2019), G20 Contribution to the 2030 Agenda: Progress and Way Forward Paris, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/db84dfca-en

PRI (Principles for Responsible Investment) (2019), Statement on ESG in Credit Risk and Ratings

Siaba Serrate, José (2019), Turning Sustainable Finance into Mainstream Finance, Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales (CARI), 6 May, https://www.g20-insights.org/think_tanks/consejo-argentino-para-las-relaciones-internacionales-cari/

USSIF (2021), Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends 2020, February

World Bank (2020), Riding the Wave: Navigating the ESG Landscape for Sovereign Debt Managers, 22 October, Washington, DC.