National governments, even in the current phase of “hyper-globalization”, have important freedom of initiative in social and economic policy. The great variety of economic and social policies around the world, even among the most open economies, proves that the welfare state has not lost its original function of compensating citizens from the risk of income variability in open economies. The claim that globalization requires rolling back the welfare state is therefore unfounded. National politics should therefore be seen by all relevant actors (policy-makers, citizens, civil society) as crucial for determining the path of their country and deserving of their investment and energy.

Challenge

The current period of “hyper-globalization” combines important international circulation of goods, services, financial flows, knowledge, and workers. It also involves the emergence of large international corporations whose size dwarfs many national economies. Such international agents have gained considerable leverage in their interactions with national policy, both through their heavy weight in determining job and economic opportunities in local markets and through favorable international norms such as the dispute resolution systems pitting them against national governments in front of private litigation bodies. Many policy-makers now refer to international constraints when pressed about their lack of effectiveness to address national challenges, and analysts point to the difficulty to combine democratic national sovereignty and global economic integration. According to Rodrik (2011) in particular, globalization requires either to lift the scale of democratic governance to the global level, leaving little policy-making at the national level, or to submit national policies to international norms, thereby reducing the scope of democratic control. At the moment, both globalization and democratic institutions suffer from growing disaffection from the population, while the sirens of nationalism, closure and xenophobia attract increasing numbers of citizens.

A critical department of national policy that is put under pressure by globalization is solidarity and welfare. Can social safety nets remain democratically determined at the national level under the pressure of global competition?

Since a global democratic governing body is politically out of question nowadays, and is not seen as desirable by most analysts because of the distance it would create between citizens and representatives, the challenge for our time is to imagine a way to preserve national democratic policy-making while making the most of the economic and social opportunities offered by the free circulation of capital, goods and services, technology, and labor.

Going back to the Bretton Woods institutions is an option that may not be possible either, given the technological transformations in financial activities, IT industries, and in global value chains. Therefore one needs to either imagine a new formula, or, more modestly, examine what degrees of freedom national government still have in the current era.

Proposal

Diversity of economic and social policies among open economies

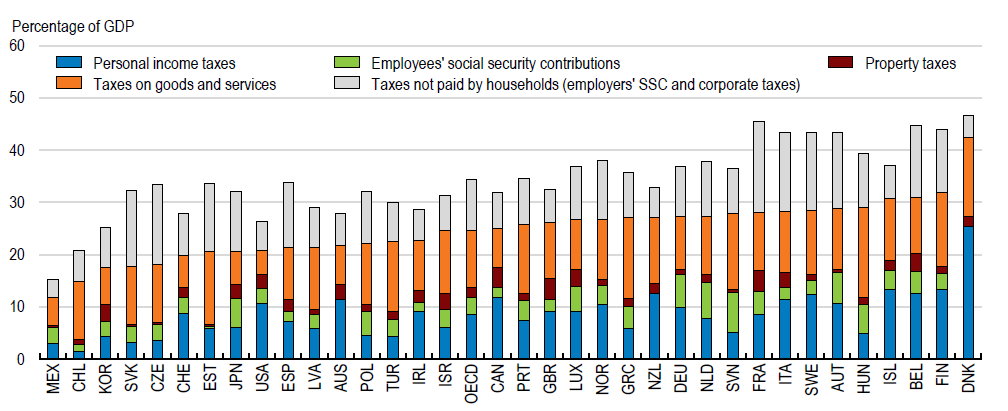

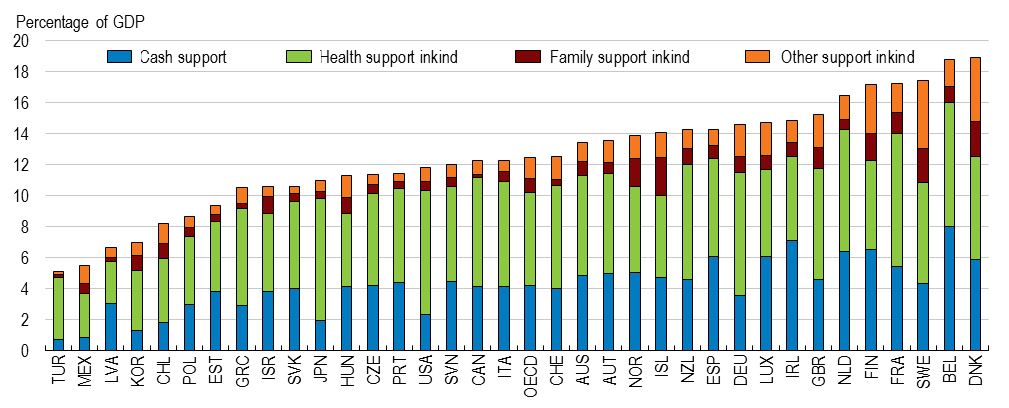

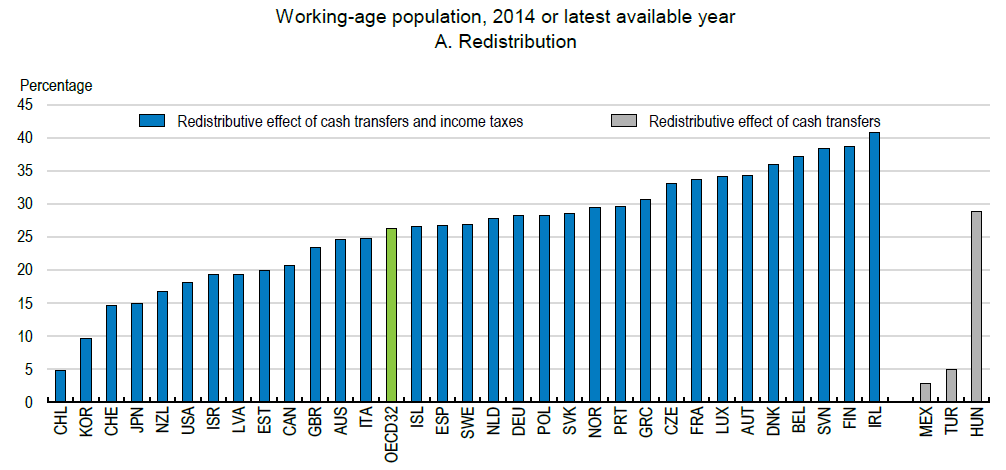

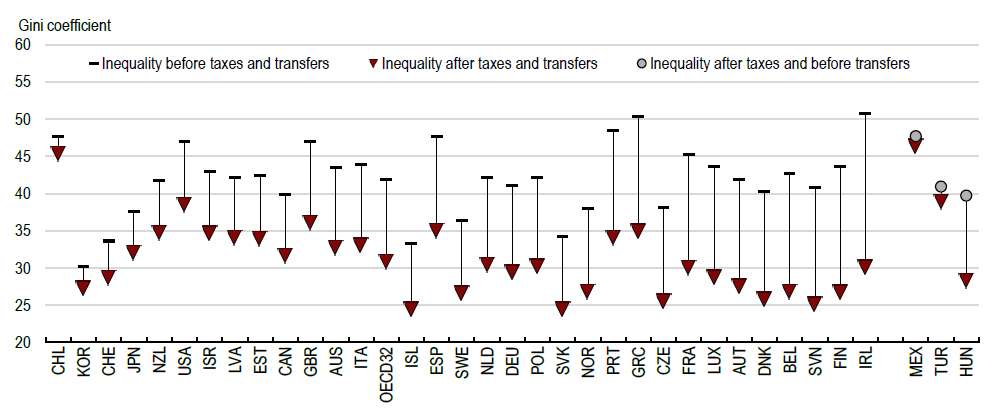

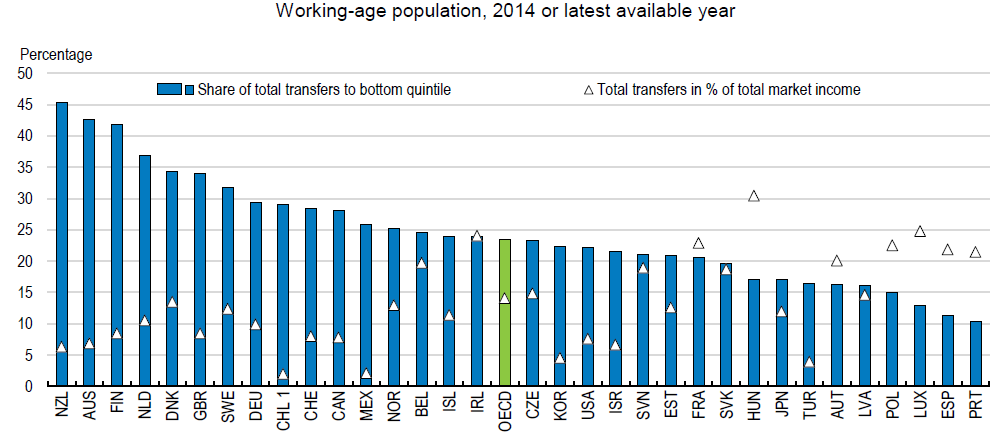

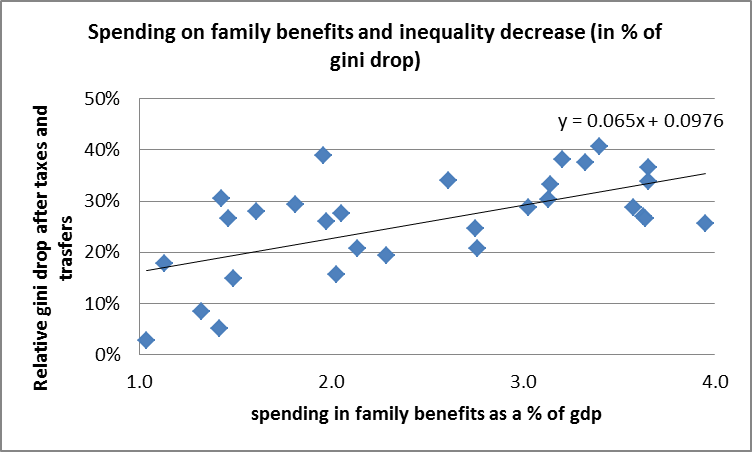

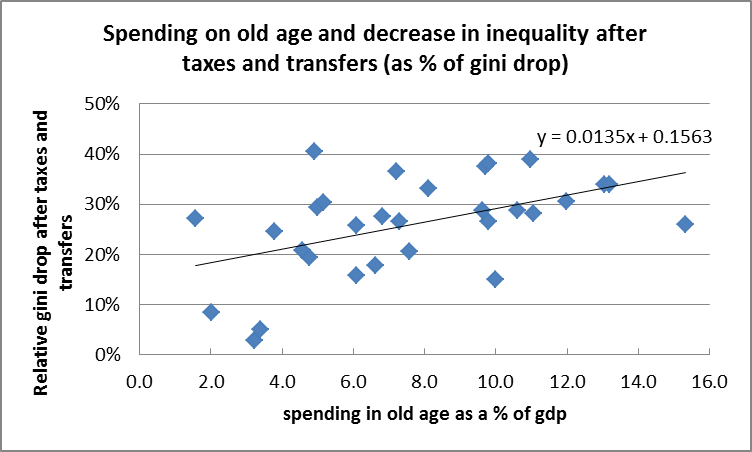

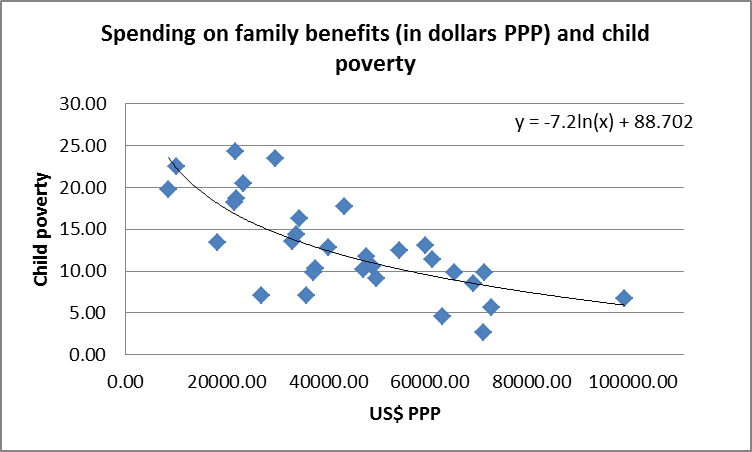

The diversity of economic and social policies belies the claim that globalization has imposed a uniform mantle of norms and policies over most countries. This is illustrated both on the revenue side and on the social spending side, in the variety of levels and composition of taxes raised from households and transfers redistributed to households (Figure 1). More significantly, the redistributive impact of taxes and transfers varies widely across countries (Fig. 2), even for similar levels of market income inequalities (Fig. 3). For example, although market income inequality stands at around 38 Gini points in both Japan and Norway, disposable income inequality is around 27 points in Norway compared to 32 points in Japan. In other words, taxes and transfers reduce twice as much market income inequalities in Norway than in Japan. Such variations partly reflect cross-country differences in the size of the public sector: the level of redistribution is strongly associated with the level of public social spending on cash support to the working-age population as well as to the level of total tax revenues. At the same time, the size of taxes and transfers cannot fully explain income redistribution, as this depends on the extent to which social spending accrues to least affluent households (Figure 4). In particular, there is a marked difference in the strong progressive distributional bend of child benefits, early childhood education and care and even maternity, paternity and parental leaves compared to a much weaker progressive –and sometimes even regressive– architecture in pension systems (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 1. Tax revenue and social spending in the OECD

Panel A. Total tax revenue raised from households, 2015

Panel B. Levels of public social spending on the working-age population, 2013

Figure 2: Percentage of reduction of the Gini coefficient

Source: Causa and Hermansen (2017).

Figure 3: Gini coefficient before and after redistribution

Source: Causa and Hermansen (2017).

Figure 4: Targeting of cash transfers to low-income households

Source: Causa and Hermansen (2017).

Figure 5: Redistribution and family benefits vs. pensions in the OECD

Source: OECD family database, OECD Social database and OECD economic database, 2018.

Figure 6: Family benefits and child poverty in the OECD

Source: OECD family database, OECD Social database and OECD economic database, 2018.

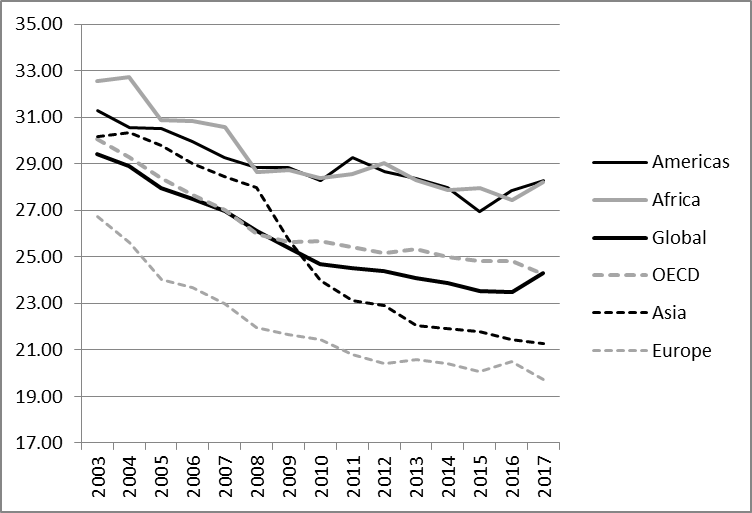

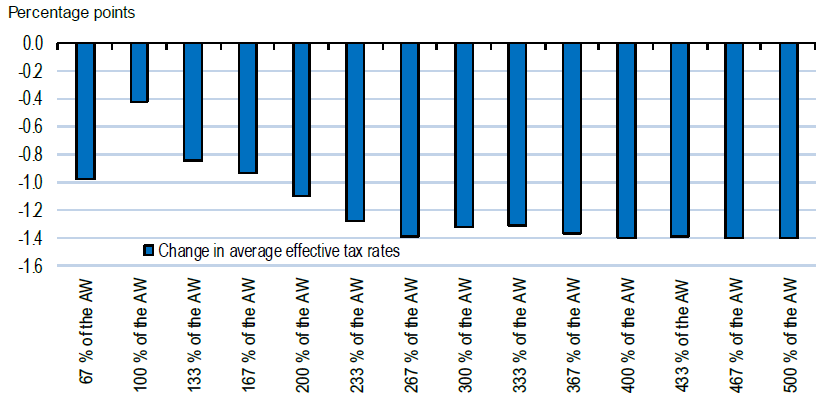

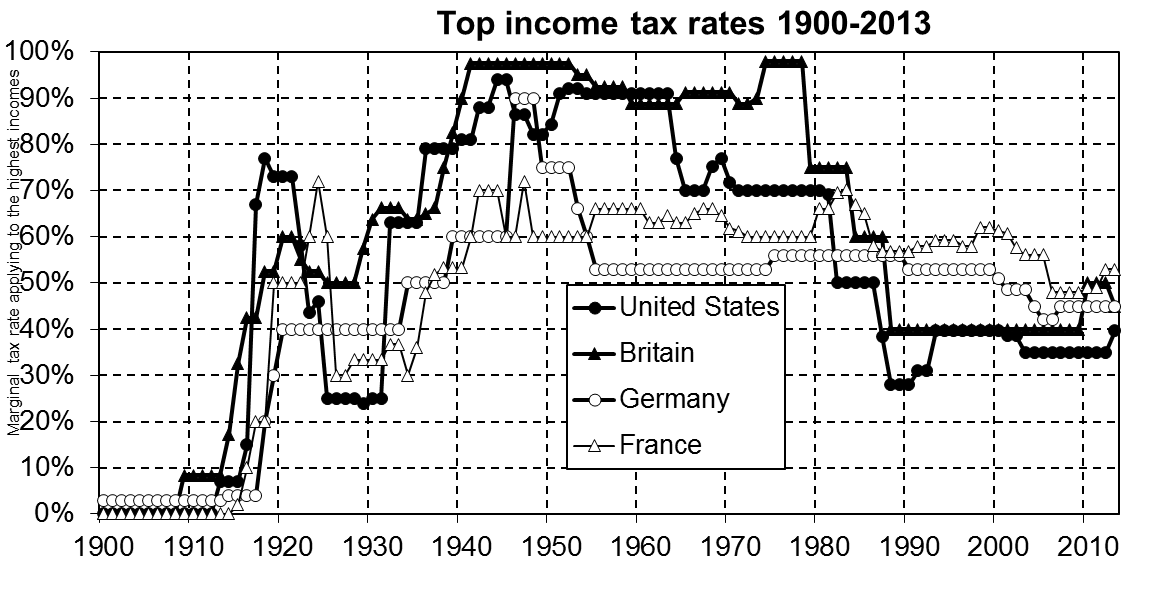

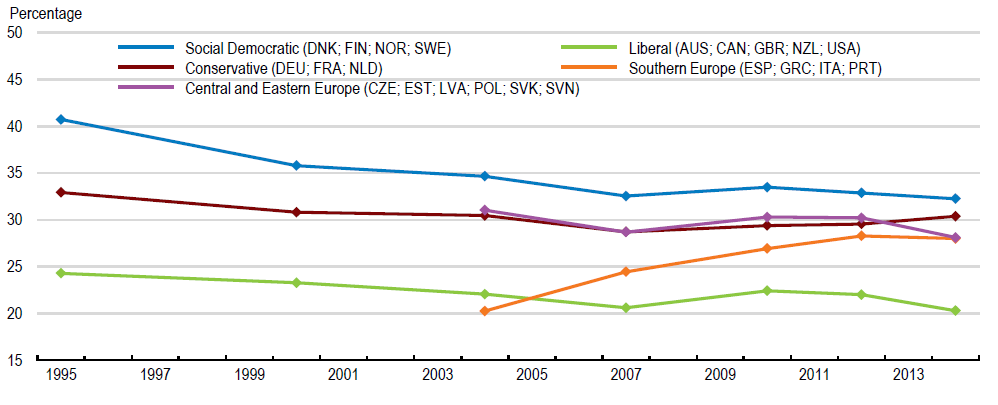

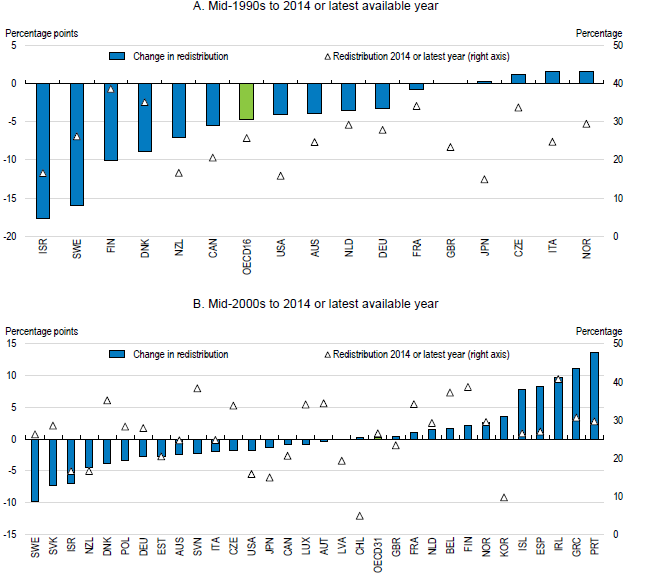

A decline in certain taxes and redistributive policies

In spite of a great variation in policies and a relative stability in general social public spending and fiscal pressure, government policies have shown some trends that suggest a reduction in tax pressure on mobile factors, such as capital (Fig. 7) and top incomes (Fig. 8) and a reduction in the extent of redistribution (Fig. 9-10). It is particularly notable that redistribution has declined most in the most redistributive welfare systems, i.e., the Scandinavian countries but those are still among the most egalitarian OECD countries. The trend towards less redistribution was most pronounced over the pre-crisis period, and was temporarily reversed during the first period of the crisis, reflecting the cushioning impact of automatic stabilizers and fiscal discretionary measures (Fig. 11).

Figure 7: Statutory corporate tax rates

Source: KPMG

Figure 8: Change in average effective tax rates across the distribution, 2000-2015

Source: Causa et al (2018).

Figure 9: Top income tax rates 1900-2013

Source: piketty.pse.ens.fr/capital21c (Piketty 2014).

Figure 10: Average redistribution trend by welfare model, working-age population

Source: Causa and Hermansen (2017).

Figure 11: Change in redistribution for the working-age population

Source: Causa and Hermansen (2017).

It should be noted that globalization is not the only force putting pressure on public policy. Another major trend to be considered is ageing and family transformation. How the state deals with the distributional implications of an ageing society and of changes in family structures will also be critical in making the state more or less able to steer growth while fostering social cohesion.

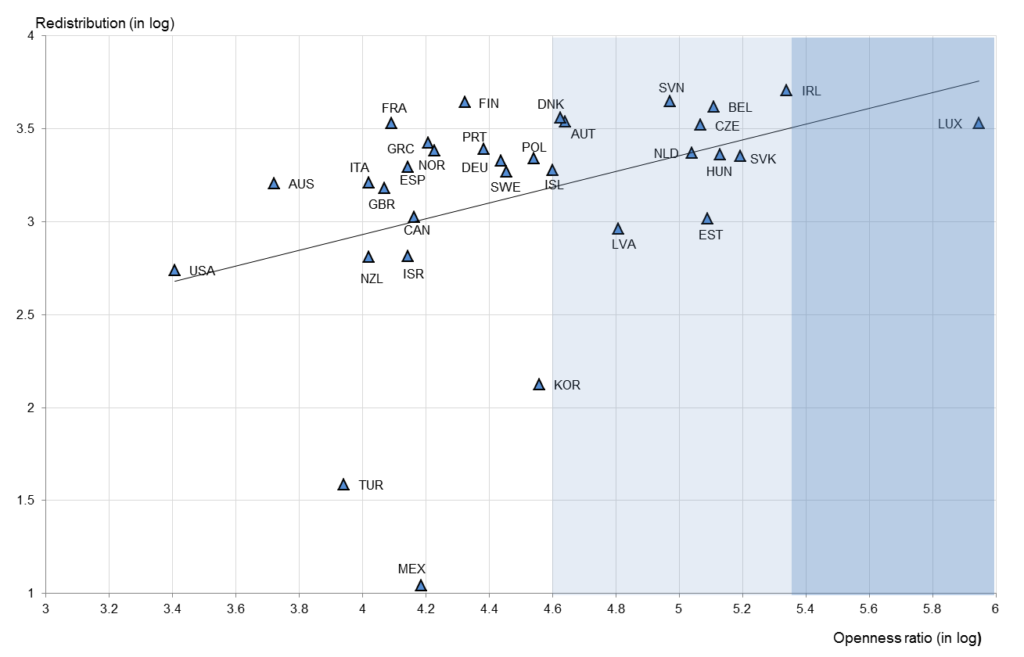

Globalization and redistribution, a complex interdependence

The previous section suggests that countries feel the pressure to redistribute less and especially to relax the fiscal pressure on mobile factors. However, the pattern of openness and redistribution suggests that these two dimensions are complementary rather than in tension (Fig. 12).

Figure 12: Openness and redistribution, 2014

Source: Causa et al (2018)

This pattern is compatible with the thesis that openness requires a high degree of insurance against the risk of income variability, especially in small countries as in Scandinavia. The social-democratic model has been using open economies as a way to discipline collective bargaining and enhance internal cooperation and high levels of technical innovation in order to ensure competitiveness and adaptability, and conversely, has implemented a high degree of social protection and solidarity to make this viable for the less advantaged citizens. Indeed, investigating the policy and non-policy drivers of redistribution, regression-based analysis in Causa et al (2018) shows that that more economic integration tends to increase income redistribution through taxes and transfers. The broad finding that rising economic integration is associated with rising redistribution is in line with the majority of comparable empirical studies, along the lines of the so-called “compensation hypothesis”. The compensation hypothesis (Rodrik, 1998, 2011) predicts that globalization increases the size of government and in particular social spending by increasing workers’ demand for compensation against risk arising from rising exposure to international economic forces; to which governments respond by expanding social safety nets.

However, extending the analysis to uncover potential interactions between globalization and income redistribution through fiscal deployment, Causa et al (2018) also find that increased economic integration has tended to reduce the redistributive effect of tax revenues, and in particular of tax revenue raised from personal income taxes and employees’ social security contributions. In other words, increased economic integration has made a given level of fiscal deployment through the tax system less effective at reducing income inequality. This result is relevant as it is fully in line with recent research that has shown that: [1] i) globalization and international tax competition have put pressure on governments in OECD countries to shift taxation towards less mobile bases, and ii) this has been achieved mainly increasing the labor tax burden on the middle and upper-middle classes while reducing the burden on the top of the distribution – leading to a decline in the progressivity of PIT. This suggests that openness does constrain the form of redistribution.

Nevertheless, one can argue that small states have demonstrated that the relationship between globalization, national governance and democracy, might not be as conflictual as Rodrik’s triangle suggests. Countries like Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Austria and others have a very high share of their economy exposed to global markets – as such they are more globalized than most. At the same time, these countries have developed their adaptiveness and competitiveness, by developing national institutions and mechanisms that promote welfare, a fair distribution of the benefits, and access to health and education. Doing so, they managed to preserve trust in democratic institutions and to preserve a high degree of autonomy in many aspects of their policies and institutions. [2]

Enhancing the effectiveness of national policies in a globalized economy

Some of the most globalized states in the world, like these small European countries, also appear on top of ranking lists of countries when it comes to democracy, equality, and well-being. Moreover, the same countries also rank high on listings related to competitiveness and rankings regarding ease of business. As argued by Katzenstein (1985) and Pareliussen et al (2018), these countries have developed adaptability through consensus-based and inclusive political processes, and also the development of tripartite cooperation (see also IPSP 2018, ch. 8). Thus, it appears that globalization or regional integration might structure the overall developments in countries, but it is in no way removing all room for national discretion and national choice. Several arguments can support this thesis.

First, global norms or regulations, standards etc. are typically vague, crude, under-specified and weak. So even if states adhere to a principle of loyalty and seek their outmost to meet their international obligations, there is still considerable discretion and possibility for national choice. There is therefore no surprise that we can observe considerable variation when it comes to policies and regulations in core areas, such as taxation, social policy, access to welfare arrangement, level of welfare arrangements, as well as policies regarding border control, policies related to migration, and integration of migrants into the labor markets, to mention some of the most contentious and disputed policy issues. Even after more than 25 years of intense integration in the EU after the launch of the Single Market, there is still considerable variation among European countries when it comes to welfare systems and levels, and in many areas there are few traces of convergence.

Moreover, we can also add that even in the most advanced regional integration processes, such as the EU, there are few mechanisms of monitoring compliance, and the cost of non-compliance is sometimes also limited. In many instances, such as EU law, the instrument of choice is often to seek that shared goals are met, while, consistent with the subsidiarity principle, it is left for national governments to find the appropriate instrument consistent with traditions as well as institutional and political particularities.

In the rich literature on governance in Europe, it is therefore often argued that policies are adjusted and changed, not solely because of external pressure from the EU, but because national politicians or actors are advocating that this is a change that they prefer. Sometimes it is also easier for politicians to blame “Brussels” or “globalization” for unpopular but sound reforms, rather than to face the arguments themselves. In other situations, politicians might push through reforms that otherwise would have been opposed nationally, with reference to a so-called need to adapt because of European or global pressure, and thereby avoiding normal national political constraints and concerns. But careful and systematic studies of compliance and the actual workings of the various agreements often find that the balance of competence between the European and the national level is quite appropriate. This was for instance also the outcome of the large “Review of the balance of competences” by the UK government prior to the referendum (UK 2012-2014), which through 32 reports and around 2300 pieces of evidence found that the balance of competences set out in the Lisbon Treaty was broadly right, and as a majority of the competences were shared they could also be adjusted if needed.

As a result of these observations, national politicians and national actors should be cautious about blaming the EU or globalization for any kind of domestic reform, or lack thereof In fact, states have numerous possibilities to either influence or prevent policies in global decision-making bodies, and they have ample possibilities to accommodate the well-being of their citizens when transposing and implementing such international norms into their national systems.

Welfare policies in emerging economies

The special case of economies that are consolidating their welfare state is worth mentioning here. Analyzing the diversity of welfare policies in emerging economies provides valuable insights into the comparative effectiveness of different models based on different types of social expenditures.

In Latin America the welfare state started with three pillars: education, health case and pension systems. Education was universal and state-led, health was dual (contributory for the middle class and free of charge for the “poor” with lesser quality) and pensions were contributory and started with civil servants, the military and a few white collar or blue collar skilled occupations. With time these systems evolved as follows. Primary education did well, but secondary education lost steam and budget. Health access was highly stratified. And pension systems remained small in coverage but very expensive given the generosity of initial parameters.

Asia (with the exception of Japan), in contrast, put little fiscal effort in pensions and much more in basic health and basic education. Now the richer Asian countries have moved towards greater spending on pensions, but in systems that are financially sound and with modest replacement rates.

Almost all OECD countries are now increasing spending in children and in protecting families with children. This should ideally go together with education and health where efforts are also placed in emerging economies’ welfare states. And as shown earlier, redistribution in the OECD is much more effectively performed via family benefits than with pensions.

These observations suggest that pensions should not be the driving force of the welfare state, and that spending on child and family benefits is much more effective, both as an investment in human capital and as a more effective redistributive tool.

The importance of domestic politics

Given that national policies can and do vary a lot across countries, with substantial consequences for the populations, national politics should retrieve its importance in the eyes of citizens and civil society.

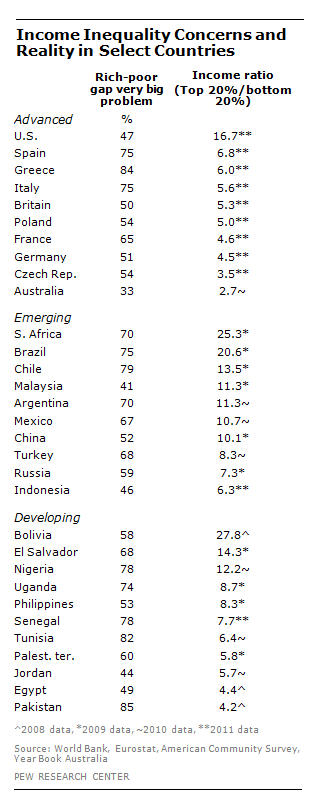

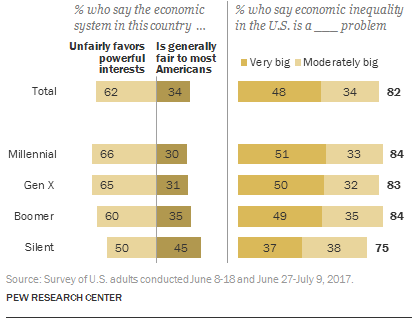

The observed disparities in the magnitude of redistribution may be the result of different demand for redistribution by citizens of different countries, but there may also be discrepancies between the wishes of the population and the implemented policies. The comparative literature highlights that preferences for redistribution are indeed broadly different across countries. According to the International Social Survey Program dataset, the percentage of people strongly agreeing with the statement that inequality in their country is too high ranges from 84% in Bulgaria to 12.2% in Cyprus (Osberg and Smeeding, 2006). On a 5-point Lickert scale, the average support for redistribution ranges from 2.9 in the US to 4.8 in Latvia. Experimental evidence also shows the existence of significant differences in preferences for redistribution between countries, as well as differences in the willingness to reward individual merit (Grimalda et al., 2018). Part of such differences in preferences may be cultural or ideological. A traditional thesis posits that part of the divide between Anglo-Saxon countries – namely, the US, Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand – and continental European countries with respect to the magnitude of redistribution is driven by different beliefs about economic mobility (Alesina and Glaeser, 2004). Citizens of Anglo-Saxon countries typically view their societies as offering upward mobility, hence they find poor people less deserving of help, as their poverty is due to lack of effort. Conversely, continental European citizens tend to think of their societies as less mobile, hence they find the poor more deserving of help. But even the US population, for instance, which stands out as being less concerned about inequalities than other countries, nevertheless thinks that inequalities are a big problem and that the economic system unfairly favors the rich, by a wide margin (see the Appendix). Other cultural or ideological factors may influence demand for redistribution, as well as the welfare state regime that is established (Dallinger, 2010). Culture and values will change over time, even endogenously or for exogenous shocks such as institutional changes, and such changes will carry over to attitudes toward redistribution (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln, 2007). Since studies on cultural change conclude that countries are far from converging to a single pattern, in spite of the homogenizing force of globalization (Inglehart and Welzel 2005), it is possible that differences in basic preferences for redistribution will endure in the future.

These points should encourage citizens to re-engage with domestic and regional democratic politics rather than desert it. In fact, it is evident that there is considerable room for national discretion and variation. The voices of voters and civil society can be heard and they can press their policy-makers and institutions to pursue policies fitting their preferences, and to encourage more transparency about the available options and to ensure that politicians are held accountable for the directions taken by national and regional polities

A final point can be made relating to the question of sovereignty and the limits of interference of international institutions in national governance. In many instances, there is a tension between state sovereignty and some more universal principles or norms, or for instance fundamental norms relating to membership in a club. In the EU, for instance, some member states want to sanction the behavior of other states for not acting according to key principles or shared values and fundamental principles. One potential risk of such initiatives is that they might turn out to be counterproductive, in the sense that they will typically lead the accused governments to blame “Brussels” even more, potentially just increasing the support for their nationalist tendencies. It is perhaps therefore important to supplement such approaches with a more effective approach to promote bottom-up mechanisms, by for instance exploring the idea of a mechanism for domestic groups to appeal to an independent European democracy watchdog if they feel that democratic rules are being violated in their country (Schlippak and Treib 2016).

[1] Egger et al (2016). These findings are also largely in line with Martinez-Vazquez et al (2012) who similarly to us show that the effect of tax on inequality is “eroded” with openness.

[2] See Pareliussen et al (2018) for an in-depth recent analysis of the Nordic model from the inequality and institutional settings perspective.

Appendix:

Younger generations are more concerned about inequalities in the US

References

- Alesina, Alberto and Fuchs-Schündeln, Nicola. Good-Bye Lenin (or Not?): The Effect of Communism on People’s Preferences. (2007). American Economic Review, 97(4): 1507–1528.

- IPSP 2018, Rethinking Society for the 21st Century, Report of the International Panel on Social Progress, Cambridge University Press.

- Causa, O. A. Vindicis and O. Akgun (2018), “An empirical investigation on the drivers of income redistribution across OECD countries”, OECD Economics Working Paper, forthcoming.

- Dallinger, U. (2010). Public support for redistribution: what explains cross-national differences?. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(4), 333-349.

- Egger, P., S. Nigai and N. Strecker (2016), “The taxing deed of globalisation”, CEPR Discussion paper DP11259.

- Grimalda, G., Farina, F., Schmidt, U. (2018). Preferences for Redistribution in the US, Italy, Norway: An Experimental Study. Kiel Working Paper, 2099, Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

Preferences for Redistribution in the US, Italy, Norway: An Experimental Study - Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge University Press.

- Katzenstein P. (1985), Small States in World Markets, Sidenius. Osberg, L and T. Smeeding (2006). “Fair” Inequality? Attitudes toward Pay Differentials: The United States in Comparative Perspective”, American Sociological Review, 450-473.

- Martínez-Vázquez J., V. Vulovic & B. Moreno Dodson, 2012. “The Impact of Tax and Expenditure Policies on Income Distribution: Evidence from a Large Panel of Countries,” Hacienda Pública Española, IEF, vol. 200(1), 95-130.

- Pareliussen, J. K., Hermansen, M., André, C. and Causa, O. (2018), Income Inequality in the Nordics from an OECD perspective, Nordic Economic Policy Review 2018.

- Schlippak B. and O. Treib 2017, Playing the Blame Game on Brussels: The Domestic Political Effects of EU Inverventions against Democratic Backsliding. Journal of European Public Policy. DOI: 10.1080/1350163.2016.1229359.

- Rodrik, D. (1998), “Why do more open economies have bigger governments?” Journal of Political Economy 106 997–1032.

- Rodrik, D. 2011, The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy, Norton.

- UK 2012-2014, Review of the balance of competences

More Information