Humanitarian organizations estimate that there are more than 25.9 million refugees and 41.3 million internally displaced persons worldwide (UNHCR 2020). Humanitarian organizations and host governments often struggle to meet the basic survival needs of communities on the move. The basics of food, shelter, sanitation, and health care are often the initial focus, with access to education forgotten. We recommend that the international community place access to education for migrant youths as a global public good and reinforce the need for strategic education partnerships to ensure that young people can continue their education, even in times of displacement.

Challenge

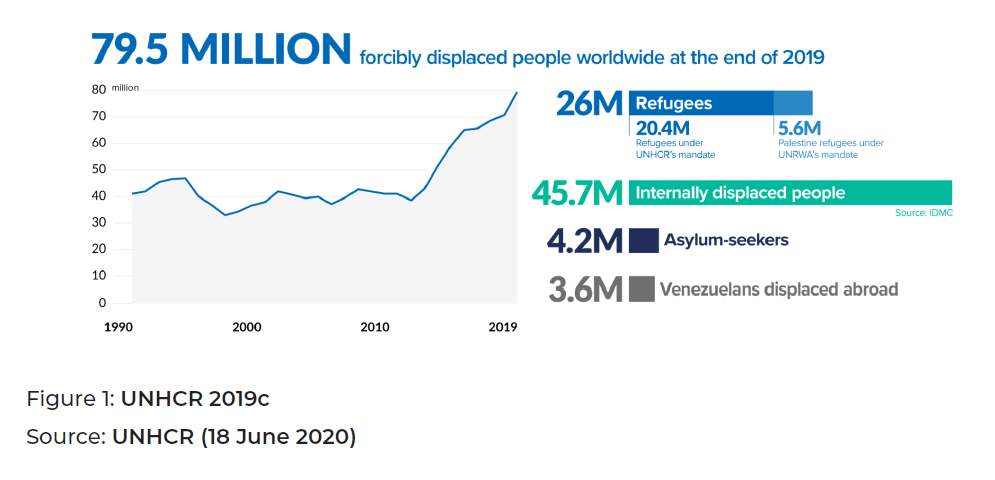

Migration is one of the main challenges of modern society. While international and non-governmental organizations focus on providing basic survival needs, often, education for youths remains an under-addressed issue. United Nations indicates that only 63 percent of refugee children go to primary school, and 24 percent of adolescent refugees have the opportunity for secondary education. Even fewer refugees and displaced youths attend university. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has highlighted that education is a priority issue for refugee and internally displaced populations and has codified education as a top human need in their 2017 Framework for Access to Education policy (ICRC 2017). At present, only 3 percent of refugee youths attend university, and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has set new targets that seek to increase enrolment to 15 percent (UNHCR 2019a). Lack of access to education limits the opportunities for children as they grow to adulthood, creates hopelessness for teens, and at risk for radicalization. The challenge with displacement is one of global scale. The United Nations reports that, at the end of 2019, close to 80 million people were refugees, internally displaced or living abroad due to instability.

The UNHCR indicates that global resettlement needs will rise in the years to come, and UNHCR’s statistical yearbook illustrates that the top refugee-hosting countries are Germany, Sudan, Uganda, Pakistan, and Turkey (UNHCR 2019a). In this paper, we focus on the unmet education needs of refugee and displaced youth, incorporate the current policy proposals from international organizations that work on displacement issues, and suggest innovative approaches to promote education opportunities to enhance basic human dignity. (UNHCR n.d. a.)

Proposal

Sustainable Development Goal Four (SDG 4) and human rights covenants speak to the need to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” The SDGs frame education as a route to poverty eradication, and international covenants speak to the role of education in human development, linking investments in education to social and economic gains in communities that host refugees.

The ICRC best captures the essential nature of education for young populations in crises with the following statement: “Humanitarian action is not simply about helping people to survive, it is also about helping people to live with dignity.” (ICRC 2017). Other humanitarian organizations, such as the UNHCR, have spearheaded a new strategy in the Refugee Education 2030 strategy that builds on the understanding of the role of education for both the individual and the community as a whole (UNHCR 2019b). The UNHCR viewpoint is that it is essential to help refugees “thrive, not just survive.” Furthermore, educators around the globe highlight the role that schools and education have in creating economic growth and socially cohesive communities, not only for new arrivals but for longtime residents.

Policy Recommendations

While the G20 has historically had a focus on economic cooperation, over the years, we have witnessed a greater dialogue on critical social issues, including the nexus between economic growth and investments in social and education infrastructure. Most recently, G20 statements during the COVID-19 era have reminded global leaders of not just economic reconstruction, but also the intertwined nature of financial markets, health investments, and social expenditure. The G20 can remind the international community of the policy issues that may be overlooked and provide the leadership necessary to encourage humanitarian communities to make more significant commitments to reduce obstacles to education. In this regard, the G20 should highlight the following.

Reiterate that education is a Global Public Good:

Education access for refugee and internally displaced children draws on a political debate that often takes on racist and nationalistic themes. A feature of the topic often includes a “scarcity mindset,” in which host nation opponents claim that immigrant and displaced populations are “taking seats away” from deserving native-born children. The G20 needs to help counter this mindset and reinforce the understanding that education is a global public good. One well-accepted definition of the concept of global public good uses the following terminology: “issues that are broadly conceived as important to the international community, that for the most part cannot or will not be adequately addressed by individual countries acting alone and that are defined through a broad international consensus or a legitimate process of decision-making.” The G20 should call on member states to ensure that policy decisions on education are framed from the global public good perspective, and reinforce the need to see education as a way to ensure that all citizens thrive (Inge and Mendoza 2003; Menashy 2009).

The ICRC and UN draw our attention to the places in human rights law where the international community has the duty to protect the right for children to have an education (United Nations General Assembly 2016; ICRC 2017). The right to education, like all human rights, imposes three levels of obligations on states: the obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill. In other words, states must refrain and prevent others from interfering with the enjoyment of the right and adopt appropriate measures toward its full realization. The right to education is economic, social, and cultural. Unlike civil and political rights, which embody an immediate obligation to respect and ensure all the relevant rights, economic, social, and cultural rights cannot always be fully realized in a short time

Increase funding:

While the G20 statements have focused on bringing the pandemic under control and protecting livelihoods, the international community has recognized that the current crisis will have a disproportionate impact on the world’s poor and vulnerable. There is a need to increase funding streams for older students to incentivize education and the completion of studies in trade schools, junior colleges, and universities. Donor nations have recognized that funding is an obstacle, and in the last decade, the Education Cannot Wait Fund has established international approaches to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Education Cannot Wait, n.d.). However, needs are outpacing resources (Dupuy, Palik, and Ostby 2019). Similarly, UNHCR’s higher education scholarship program has helped more than 15,500 refugee students gain access to tertiary education in their country of asylum (UNHCR n.d. b.). As the cost of higher education is on the rise, there needs to be a concerted effort to end the ad hoc approach to funding education for children in refugee and displacement scenarios and additional funding dedicated to scholarships for tertiary education in G20 member states.

Promote lifelong learning:

Host nation countries need to open opportunities for new arrivals to access existing education systems to allow students to catch up in their studies and become productive members of their new host country. There are existing models of success in various parts of the world that can be used as a benchmark for the interplay between different types of education and training programs. One such example comes from the Puente Center in Los Angeles, where migrant youths have the opportunity to attend educational programs that focus on all stages of education and have a family focus. The Puente philosophy recognizes that each member of the family has a different schooling need; for example, parents need language and computer training. In contrast, very young children need preschools, and school-age children need aftercare, tutoring, and exam preparation. Looking at education not only from a youth’s perspective, but the needs of the whole family, helps generations succeed and become vital members of the community.

Additionally, alternative admissions procedures for new arrivals need to be researched. One aspect of collaboration between universities has to do with the documentation students require to attend school. When children spend a prolonged time in transit, with perhaps years spent in internally displaced camps, it is not possible to obtain a traditional transcript, leaving certificate, or other documentation that demonstrates proof of educational credentials. Colleges and universities should work together to create standardized options to grant admission to migrant students who are not able to gather formal documentation from their home country. Similarly, universities and colleges should work with feeder schools, such as community colleges, to help create affordable pathways for refugee youth to obtain remedial courses required for college success.

There is an information gap for many immigrants and displaced families on the exact pathway to higher education. It is positive that more schools are recognizing the need to open education opportunities for new arrivals. Still, unless there is an outreach program to help families understand the differences between the rules and procedures for admission, the opportunities will remain a mirage. Leaders in education should explore opportunities for creating standardized exams that can help youths to overcome the documentation of education problem that serves as a barrier to obtaining a college degree.

Communicate pathways:

The international community has set a target to increase the number of refugees and displaced youths attending university, but what is often lacking is a clear pathway to access higher education. Obtaining a quality education in secondary school is a prerequisite for success at university. Secondary schools must partner with universities to help students understand funding pathways and curriculum preparation for success. Universities should begin a dialogue collaboratively, perhaps with a regional focus, to determine how to reduce the obstacles for refugees to attend university. In addition to the approach to create a unified policy by region, the schools should work in coordination with international refugee and humanitarian organizations. Together, they must gain insights into how to ensure that students can thrive in a secondary school in a way that sets them up for success in higher education.

Strengthen the community of interest:

While donor nations and philanthropic organizations have focused more significant funding and attention on the education deficit, those with the ability to help bridge the education gap lack coordination. Under the auspices of the G20, a working group must be established that unites stakeholders from G20 member countries, humanitarian organizations, and other policymakers to agree on targets and create strategic plans. Without unity of effort from stakeholders in the G20, it will be difficult to meet the established targets.

Relevance to the G20

Migration is a critical issue that global policymakers must address from political, economic, and social perspectives at a strategic level. While long term solutions and policy options are necessary, populations on the move require options. Previous Think 20 (T20) Summits have addressed the issue of access to education with a broad number of T20 Policy Papers, as follows:

- Transforming Education towards Equitable Quality Education to Achieve the SDGs (Tanaka et al. 2019)

- Early Childhood Development Education and Care: The Future is What We Build Today (Urban et al. 2019)

- Developing National Agendas in Order to Achieve Gender Equality in Education (SDG 4) (Ridge et al. 2019)

- Measuring Transformational Pedagogies Across G20 Countries to Achieve Breakthrough Learning: The Case for Collaboration (Istance, Mackay and Winthrop 2019)

- Teacher Professional Skills: Key Strategies to Advance in Better Learning Opportunities in Latin America (González D et al. 2019)

- Bridging the Gap Between Digital Skills and Employability for Vulnerable Populations (Lyons et al. 2019)

The G20 has tackled the issue of education access in prior statements, but often from the perspective of comprehensive immigration reform and establishment of ombudsman services for migrants. Other G20 approaches have looked at immigration from a social cohesion standpoint and have highlighted the role of community service as a way to help bridge the divide between immigrant and host nation populations. The G20 has yet to focus on the challenge of education access for migrant populations from the standpoint of tertiary access for university or technical training for young adults.

Disclaimer

This policy brief was developed and written by the authors and has undergone a peer review process. The views and opinions expressed in this policy brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the authors’ organizations or the T20 Secretariat.

References

Dupuy, Kendra, Julia Palik, and Gudrun Ostby. 2019. “Walk the Talk? Review of Financing

for Education in Emergencies, 2015–2018.” Save the Children Norway. Accessed

August 20, 2020. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/walk-talk-review-financing-education-emergencies-2015-2018.

Education Cannot Wait. n.d. “About Us.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.educationcannotwait.org/about-ecw.

González D., Javier, Dante Castillo C., Claudia Costin, and Alejandra Cardini. 2019.

“Teacher Professional Skills: Key Strategies to Advance in Better Learning Opportunities

in Latin America.” T20 Japan. https://t20japan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/t20-japan-tf1-6-teacher-professional-skills.pdf.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). 2017. “Framework for Access to

Education.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/icrc-framework-access-education.

Istance, David, Anthony Mackay, and Rebecca Winthrop. 2019. “Measuring Transformational

Pedagogies Across G20 Countries to Achieve Breakthrough Learning: The

Case for Collaboration.” T20 Japan. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-measuring-pedagogies-g20-countries-achive-learning.

Kaul, Inge, and Ronald U. Mendoza. 2003. “Advancing the Concept of Global Public

Goods.” In Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization, edited by Inge

Kaul, Pedro Conceição, Katell Le Goulven, and Ronald U. Mendoza. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Lyons, Angela C., Josephine Kass-Hanna, Cristobal Cobo, and Alessia Zucchetti. 2019.

“Bridging the Gap Between Digital Skills and Employability for Vulnerable Populations.”

T20 Japan. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332013345_Bridging_the_Gap_Between_Digital_Skills_and_Employability_for_Vulnerable_Populations.

Menashy, Francine. 2009. “Education as a Global Public Good: The Applicability and

Implications of a Framework.” Globalisation, Societies, and Education, 7, (3): 307–20.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14767720903166111.

Ridge, Natasha, Susan Kippels, Alejandra Cardini, and Joannes Paulus Yimbesalu.

2019. “Developing National Agendas in Order To Achieve Gender Equality in Education

(SDG 4).” T20 Japan. https://t20japan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/t20-japan-tf1-4-national-agendas-achieve-gender-equality-education.pdf.

Tanaka, Shinichiro, Shimpei Taguchi, Kazuhiro Yoshida, Alejandra Cardini, Nobuko

Kayashima and Hiromichi Morishita. 2019. “Transforming Education Towards Equitable

Quality Education to Achieve the SDGs.” T20 Japan. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-transforming-education-towards-quality-education-sdgs.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). n.d. a. “Comprehensive

Refugee Response Framework.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/comprehensive-refugee-response-framework-crrf.html.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). n.d. b. “DAFI Program.” Accessed

August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e4a2dd6.html.

United Nations General Assembly. 2016. “The New York Declaration for Refugees and

Migrants.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/57e39d987.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019a. “Stepping up: Refugee

Education in Crisis.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/steppingup/wp-content/uploads/sites/76/2019/09/Education-Report-2019-Final-web-9.pdf.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019b. “Refugee Education

2030: A Strategy for Refugee Inclusion.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/5d651da88d7.pdf.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019c. “Figures at a Glance,

Statistical Yearbooks.” Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-ata-glance.html.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. “Internally Displaced People.”

Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/internally-displaced-people.html.

Urban, Mathias, Alejandra Cardini, Jennifer Guevara, Lynette Okengo, and Rita Flórez

Romero. 2019. “Early Childhood Development Education and Care: The Future is What

We Build Today.” T20 Japan. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-early-childhood-development-education-and-care.