This policy brief sets out recommendations to achieve a new multilateral framework of trade rules in the digital arena, thereby facilitating continued digital transformation of services and growth in cross-border flows of data. The present moment is critical. Successful conclusion of World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations on E-Commerce will support trade in digital services, underpinned by cross-border data flows, complementing the expected recovery in travel and tourism services to provide a robust basis for global economic recovery and sustainable and inclusive growth. If the talks stall and fail to complete in 2022, technological change threatens another serious blow to a global institution which is reeling and seemingly unable to manage the regulatory heterogeneity resulting from national policies that threaten to compartmentalize data governance and fragment the global digital economy.

BACKGROUND

Digital transformation is challenging all aspects of our economies and societies. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend towards online work, education, professional and social communication and entertainment, and altered consumption habits, shifting them to electronic exchange, sales and purchases. Digitalization will further increase the role of services in the economy. E-commerce is increasingly drawing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) into the global marketplace, providing them with a platform to buy and sell inputs and products from anywhere in the world. More than 80% of SMEs report that online sales are vital to their business success (McKinsey Global Institute, 2016).

Data flows enabling and accompanying digitalization are a central feature of new business models and product innovation. Policies related to cross-border data flows affect international trade opportunities, in turn determining the scope for digital connectivity and data sharing to contribute to realizing the Sustainable Development Goals. As noted in Borchert et al. (2020), there is a disconnect between the growing digitalization of international trade and the rules that govern the multilateral trading system. Differences across G20 members on the relationship between the state and business, the state and citizens and business and individuals are reflected in divergent regulation of data flows and personal privacy protection. Minimizing trade and competition-reducing effects of national regulation of cross-border data flows will determine the future prospects for digital trade growth.

Many issues relevant to digital trade and e-commerce are not currently covered by WTO disciplines. The WTO needs urgent updating to offer global governance for digital trade. To remedy this gap, the Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on Trade-related Aspects of E-Commerce was launched at the 11th WTO Ministerial Council (MC11) in 2017. In December 2020 a draft consolidated negotiating text was circulated, divided into five broad issues: enabling e-commerce, openness, trust, telecommunications, market access and additional cross-cutting issues.

Challenge

Proposal

CHALLENGES AND PROPOSALS

CROSS-BORDER DATA FLOWS

Cross-border movement, storage and use of data has become crucial for trade and production; including for day-to-day operations of international corporations. As important, free flow of data creates opportunities for small firms and women to leverage a forecast 5.3 billion internet users by 2023 (CISCO, 2018-2023). The capacity to seize these opportunities is threatened by the rapid increase in data regulations which impinge on cross-border data flows, ranging from making data flows conditional on adequacy determinations or discretionary approvals to case by case bans on data exports, as well as local storage and processing requirements.

The need to ensure the cross-border flow of data, including personal data, for the conduct of international business cannot and should not undercut governments’ ability to regulate data flows for legitimate purposes, including personal data privacy, cybersecurity concerns and national security. What is needed is that regulatory regimes minimize adverse trade effects. Many WTO members are resorting to regional trade agreements (RTAs) and Digital Economy Agreements (DEAs) to strike this balance, but apparent differences in the disciplines on data flows across RTAs are leading to sub optimal business outcomes. The G20 must identify new ways to balance this tension especially at the WTO.

Solutions

1. Encourage consideration, in the WTO E-Commerce negotiations, of provisions being adopted in recent RTAs including as highlighted in the Annex.

2. Ensure that the outcomes from the JSI on E-Commerce are legally incorporated as additional commitments in WTO members’ GATS schedules of specific commitments. G20 members should ensure that the additional commitments do not conflict with the provisions of the GATS, fall outside the GATS remit or undermine the rights and obligations of non-participants.

3. Offer technical assistance to developing countries that wish to improve and upgrade data protection laws and regulation in the context of greater digitalization.

PRIVACY STANDARDS

The collection of personal data generated by digital economic and social interactions is growing and has become a source of concern for users of digital technologies. Approaches to personal data protection differ, influenced by diverse cultural values, policy preferences and legal traditions. Some jurisdictions view personal data protection as a matter of individual privacy rights and have implemented omnibus privacy legislation. Others view it more as a matter of consumer protection and follow a piecemeal legislative approach for specific sectors or types of data.

There is solid evidence of the significant extent of trade costs stemming from such regulatory heterogeneity (Nordås, 2016). Disparate privacy regimes create different rights and obligations for governments, data subjects and data controllers, raising compliance costs for companies. This disproportionately affects SMEs and micro SMEs, compromising their chances to tap into the trade opportunities offered by digital technologies. The deepening of these differences risks fragmentation of digital markets to a point of no return.

Solutions

1. All G20 members should join the JSI on Services Domestic Regulation as commitment to principles for good regulatory practice will assist significantly. The G20 should endorse good regulatory practices, including impact assessment of proposed regulations, stakeholder consultations and retrospective evaluations to ensure the quality of personal data protection laws and regulations, including that regulations are necessary and proportionate to the purpose, avoiding unnecessary, duplicative or inefficient regulations.

2. Encourage interoperability of data privacy approaches and reference to international standards, principles, guidelines and criteria when developing national personal data protection regulations, to enable cross-border flows of data to be appropriately safeguarded.

3. The G20 should pledge capacity building assistance for developing countries to enhance awareness and understanding of the importance of personal data protection laws and regulations that satisfy international standards, principles and guidelines, and to support them to introduce reforms aimed at developing or aligning their laws.

4. Foster international regulatory cooperation, including open dialogue and sharing of best practices to build trust in e-commerce, including by ensuring effective protection of personal data transferred across borders.

5. Recognizing that countries are adopting different approaches to protecting personal data, the G20 should encourage development of mechanisms to promote interoperability. This should start with ensuring legal frameworks make clear that firms with a legal nexus in a jurisdiction are responsible for managing data in a certain way, wherever the data is transferred and stored. A country’s data-protection rules thereby travel with the data.1

6. Further steps towards interoperability can build on approaches in recent DEAs, including:2

(a) Recognition of regulatory outcomes, whether autonomous or by mutual arrangement, preferably minimizing the risk of discrimination, by designing mutual recognition agreements in an open and transparent manner, offering due process guarantees to any party wishing to apply to join;

(b) Support for exchange of information on such mechanisms applied in the jurisdictions of the parties and exploration of ways to extend them to promote compatibility.

(c) Encouragement of adoption and recognition by businesses of data protection trust marks that would help facilitate cross-border data transfers while protecting personal data.

CYBERSECURITY STANDARDS

Cybersecurity is essential for digital trade, creating trust for internet users and businesses. But there is an important balance to get right. Overregulation will interfere with digital innovation and competition; under-regulation will increase cyber threats and reduce trust in digital trade. The economic costs of getting it wrong are very high both for digital trade and for cybersecurity governance. A range of cybersecurity measures are being introduced that can inhibit digital trade.3 Some countries ban certain digital technologies on grounds of national security in case digital products contain malware, spyware or enable the conduct of unauthorized surveillance. In some cases, government procurement of foreign digital technologies is restricted. Restrictive unilateral cybersecurity measures increase business uncertainties and reduce the quality and choice of business offerings.

Solutions

1. As cybersecurity is an important precondition for cross-border data flows, the G20 should strive for greater international regulatory cooperation on cybersecurity.

2. Support consensus-based international standards development to ensure interoperability of cybersecurity frameworks while reducing the costs of regulatory friction.

OTHER DIGITAL STANDARDS

Technical Standards, when built around international consensus, represent internationally recognized guidelines and frameworks that facilitate economic activity, enhance competition and boost industry. Up to 80% of global trade is affected by standards or associated technical regulations (Outsell, 2017). As is the case for the traditional economy, the development and adoption of consistent international standards, through collaborative technical input of both governments and the private sector, will be fundamental to enabling trade in the global digital economy. Widespread adoption of international standards in ICT has already demonstrably increased interoperability and security across technology platforms, decreased barriers to trade, ensured quality and built greater public and user trust in digital products and services. By adopting common standards, countries can avoid redundant efforts and technical duplication, achieve a higher level of interoperability and lower trade costs.

There is increasing evidence of a global race under way for unilateral dominance in extraterritorial digital standards-setting that goes well beyond the issues of privacy and cybersecurity, and which is increasingly oriented to achieving market dominance by capturing the technical specifications of all digital technologies including distributed ledgers, artificial intelligence and the internet-of-things. It is vital for the inclusive growth of the global digital economy that WTO members commit to supporting the multilateral standardization system by increasing their investment in the collaborative international processes available through the international standards development bodies rather than strive for unilateral dominance.

Solutions

1. G20 members should work together in the international standards bodies to develop and adopt globally competitive, open and market-driven standards rather than independent national standards which have less global stakeholder input and scrutiny.

2. Encourage international standards bodies to intensify their work programmes to focus on international standards relevant to data flows and digital transactions.

3. Refrain from engaging in unilateral extraterritorial application of digital standards and signal joint commitments to international regulatory dialogue, cooperation and collaborative regulatory sandbox experimentation.

WTO MORATORIUM ON CUSTOMS DUTIES ON E-TRANSMISSIONS (MORATORIUM)

At the very time when the uptake of digital technologies offers tremendous reductions in the cost of doing international business and unprecedented opportunity for more inclusive economic integration, the divergent regulatory response across multiple jurisdictions is risking serious dis-integration of the global marketplace. The WTO Moratorium has stood as a global beacon of hope that governments will continue to find ways of avoiding beggar-thy-neighbor policies as the shift to digitalization intensifies.

For 20 years, the global trading system has benefitted from the absence of tariffs on e-transmissions. The moratorium allowed business innovation to take place everywhere, at all levels of firm size and in all countries, spurring participation in global services outsourcing and many other types of business services exports. A steadily increasing number of WTO members are committing in RTAs to permanent application of the WTO Moratorium. Extensive economic and anecdotal business evidence points to the importance of the moratorium for the continued global growth of digital trade (Makiyama and Narayanan, 2019; Andrenelli and Lopez-Gonzalez, 2019).

Solutions

1. G20 members should lead the way in upholding the WTO Moratorium; by explaining the benefits and by providing technical assistance on how to meet collection challenges with Value-added Tax (VAT) and Goods and Services Tax (GST).

2. In the event of pending failure to secure agreement at MC12 to extend the moratorium indefinitely, the onus will be squarely on G20 members to, as a minimum, mobilize WTO members to extend the moratorium at MC12 for longer than the traditional two-year period which pertained throughout the first two decades of the WTO Work Program on E-Commerce.

3. A minimum four-year extension period should be agreed at MC12, given the JSI on E-Commerce currently under way and its associated discussions on the moratorium.

E-COMMERCE-RELATED SERVICES MARKET ACCESS

The GATS experience has shown that, to be truly effective, new rule making needs to go hand in hand with market access liberalization. Liberalizing trade in computer and related services, electronic payments (e-payments) and other financial services, logistics, telecommunications and data processing would make a significant contribution to facilitating the ongoing growth of e-commerce, for both goods and services, and make new e-commerce disciplines fully effective. Agreement to negotiate on market access in the context of the JSI is not yet unanimous but to sustain negotiating momentum and the engagement of private sector stakeholders, an exchange of offers needs to take place before the end of 2021.

Existing GATS market access commitments date from a time when digital technologies were much less prevalent. Stronger WTO commitments, even if merely to reflect current trading conditions, are long overdue and would help to rebuild stakeholder perceptions of WTO credibility. There is much scope for new bindings, in both the GATT and the GATS, given the considerable liberalization achieved in many RTAs. For two decades now the WTO Council on Trade in Services in Special Session (CTS-SS) has suffered from general inertia, prompting interest in the plurilateral approach. However, this route remains open, has recently been reactivated and deserves full G20 support.

Solutions

G20 members should:

1. Endorse the exploratory market access discussions on different clusters of services that are currently underway in informal open-ended meetings of the WTO Council on Trade in Services, including on Logistics Services, Financial Services, Tourism Services, Environmental Services and Agriculture related Services.

2. Commit to exchanging market access requests on services that enable e-commerce, as outlined above.

3. Consider extending, for all services sectors, the market access commitments already undertaken by some WTO members in accordance with the Understanding of Commitments on Financial Services to limit the right of members to take measures preventing transfers of data or processing of data, including by electronic means.

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AND THE GATS REFERENCE PAPER

The GATS Reference Paper on Telecommunications from 1996 is outdated. It was designed at a time when mobile telephones were used primarily for local, short and expensive voice calls and before the internet became a global marketplace. A systematic study of the enforcement and impact of telecommunications chapters in recent RTAs would help in modernizing the Reference Paper. Such a study could draw on work by the International Telecommunications Union on best-practice regulation and propose a path to efficient, technology-neutral polices that address possible abuse of market power that could undermine market access.

Solutions

1. G20 members should revisit the Telecommunications Reference Paper in the light of technological developments and changes in market structure over the past 25 years.

2. The G20 should work towards replacing the Reference Paper with technology-neutral rules with flexibility for WTO members to regulate where needed and apply competition law where regulation is not needed.

TAXATION

Double non-taxation is exacerbated in the digital economy where scale without mass has enabled companies to service a global market from a few production facilities often located in low-tax jurisdictions. The digital economy has brought cross-border tax spillovers to the G20 policy agenda, notably through the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The trade dimension of indirect taxation relates to the collection of VAT and GST on cross-border digital shopping. The BEPS Action Report 1 recommends that VAT or GST follow the destination principle combined with effective collection on cross-border supplies of services and intangibles (OECD, 2015). Depending on the effectiveness of collection and the tax incidence of VAT, this also solves some of the problems of non-taxation of digital platforms.4

BEPS includes two pillars to address the double non-taxation problem. Pillar 1 covers nexus and profit allocation, while pillar 2 covers a minimum level of taxation. At their meeting in June 2021, the G7 Finance Ministers committed to a global minimum tax of at least 15% and to strongly support work at the OECD/G20 on the allocation of taxing rights. An agreed framework is scheduled for July 2021.

Meanwhile, several WTO members have introduced digital sales taxes (DSTs), imposing a revenue tax on large foreign-owned technology companies without local commercial presence. The DST is built on the premise that value is created by users of digital services, and such value should be taxed where it is created. However, the DSTs introduced or suggested to date might breach WTO commitments and rules when by design they are levied on specific foreign companies. The G7 Finance Ministers at their meeting in June agreed to a coordinated removal of DSTs as the new OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework rules are implemented.

Solutions

G20 members should:

1. Agree to implement the destination principle for VAT and GST and find efficient collection systems that do not require firms to establish in each jurisdiction.

2. Clarify the concept of value creation. In the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, a tax nexus based on where value is created should apply horizontally to all sectors and firms.

3. Take an early lead in rolling back de facto discriminatory digital services taxes.

ANNEX

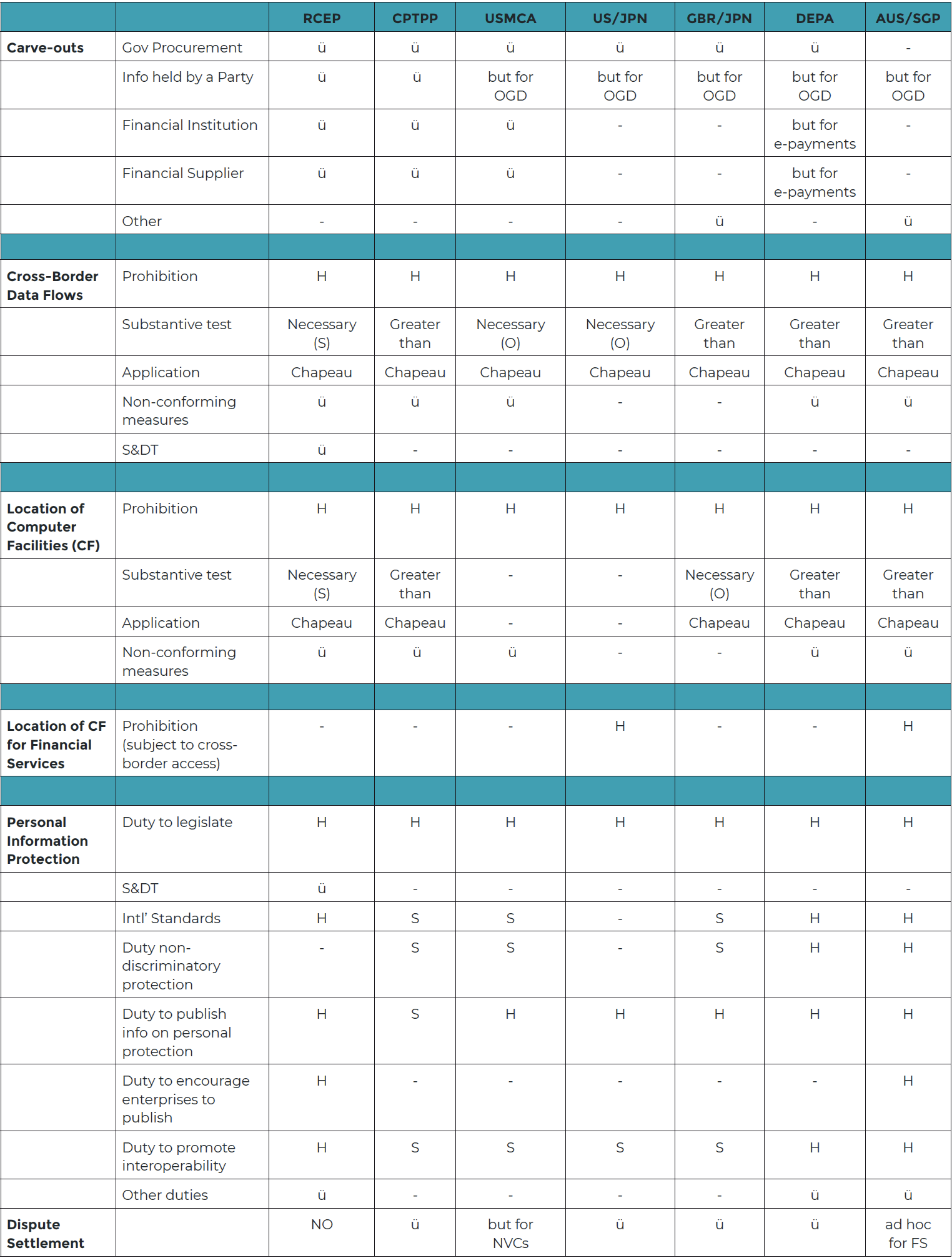

Summary Table of Digital Trade Provisions in recent RTAs

Note: H: phrased in hard terms; S: phrased in soft terms; (S): subjective test; (O): objective test; NVC: non-violation complaint; FS: financial services; OGD: open government data. Chapeau: duty not to apply the measure in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade.

NOTES

1 Specific models of interoperability include the APEC Privacy Framework and the OECD Guidelines governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data.

2 The approaches listed here are drawn from the trilateral Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. See DEPA (2020).

3 What follows draws on Mishra (2020).

4 Data value chains are observed in all sectors of the economy. Scholars describe them as a sequence of data collection, information creation and value creation. Raw data is abundant, non-rival and has value only when processed and used. Thus, value is created from the use of information. However, this is not new and applies to all sectors (Lim et al., 2018).

REFERENCES

Andrenelli A, Lopez-Gonzalez J (2019). Electronic transmissions and international trade-shedding new light on the moratorium debate. Working Party of the Trade Committee. 4 November. OECD Publishing Paris

Borchert I, Cory N, Drake-Brockman J, Fan Z, Findlay C, Kimura F, Lodefalk M, Nordas H.K, Peng S-Y, Roelfsema H, Rizal Y.D, Stephenson S, Tu X, Van der Marel E, Yagci M (2020). Impact of digital technologies and the fourth industrial revolution on trade in services, THINK 20 Policy Brief. https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/impact-of-digital-technologies-and-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-on-trade-in-services/ accessed 23 July 2021

CISCO Annual Internet Report (2018-2023)

DEPA (Digital Economy Partnership Agreement) (2020). Digital economy partnership agreement between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/digital-economy-partnership-agreement-depa/depa-text-and-resources/ accessed 23 July 2021

Lim C, Kim KH, Kim MJ, Heo JY, Kim KJ, Maglio PP (2018). From data to value: A nine-factor framework for data-based value creation in information-intensive services. International Journal of Information Management 39:121-135

Makiyama HL, Narayanan B (2019). The economic losses from ending the WTO moratorium on electronic transmissions. ECIPE Policy Brief No. 3. Brussels

McKinsey Global Institute (2016). Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows., McKinsey & Company, March, 2016

Mishra N (2020). The trade: (Cyber)security dilemma and its impact on global cybersecurity governance, Journal of World Trade Law 54(4):567-90

Nordås H (2016). Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI): The trade effect of regulatory differences. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing Paris. https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlz9z022plp-en

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development) (2015). Addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy, action 1 – 2015 Final Report, OECD/ G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241046-en

Outsell (2017). Global Standards Publishing Market: 2017. Market Size Share Forecast Trend Report 20 June 2017. Burlingame, CA: Outsell