Abstract: The immigration exchange between Canada and origin countries is a vital part of the economic growth and stability of the countries involved. The exchange, however, is often unequal, socially unbalanced and leaves Canada open to criticism that its immigration practices are exacerbating global systemic inequality at the expense of vulnerable populations. As the beneficiary of immigrant talent, the private sector can and should have a voice in helping create an exchange that is both economically beneficial for itself and Canada, and socially beneficial for the immigrants and the origin countries. Businesses can do so by driving corporate and talent strategies that push beyond a short-term, often transactional, focus. While this paper addresses immigration challenges specific to Canada, these challenges—and the opportunities for the private sector to help improve the exchange for all parties involved—are similar and can be applied to many G20 nations with declining fertility rates and ageing populations.

The Challenge: In the past five years, immigration to Canada has significantly expanded, cementing a symbiotic exchange that is generally good for immigrants and necessary for Canada.[1] Indeed, there are few places as favourable for immigrants as Canada, with its good jobs, a welcoming and diverse community and a need for their skills. In return, immigrants help maintain and build Canada’s economic growth. This is existential to Canada, given that over the next ten years, the country will be 100% dependent on immigration for its labour market[2] and population growth[3] due to its falling birth rate and ageing population. Yet, as good and necessary as this exchange is, it’s still unequal and unsustainable as currently structured. Challenges with skills accreditation, labour opportunities and social integration within Canada are fostering immigrant disconnect and poor integration into Canadian society. Furthermore, this movement of immigrants out of their home countries is creating a talent gap that can extend for generations, threatening to leave some origin countries without the necessary intellectual capital needed to create a thriving and growing economy.

Canada’s ability to generate economic activity over the next decade and beyond must come from immigrant labour, in part because the country’s fertility rate has been below the no-migration population replacement level since 1971.[4] Immigrants currently account for up to 90% of Canada’s labour force growth,[5] and in the next five years, immigrants are expected to account for 100% of net labour force growth.[6] They have accounted for between 75% and 80% of population growth since 2016[7] and by 2032, they will account for 100% of Canada’s population growth.[8]

Canada’s immigration growth plan is ambitious, and in 2022, the country allocated CAD$3.99 billion over the next five years for achieving Canada’s immigration plan as well as the efficiency, effectiveness, and integrity of its programs.[9,10] That same year, Canada planned on admitting 432,000 new permanent residents, of which more than 55% were to be economic migrants.[11] And that number is expected to grow to 500,000 per year by 2025, of which 60% will be economic migrants.[12,13,14] Between 2016 and 2021, two-thirds of economic migrants entered through one of the skilled worker programs (34.5%) or the Provincial Nominee Program,[15] a process that is designed to favour skilled and educated individuals. This plan also includes developing a pipeline of talent from the international students studying at Canadian universities, and the program has facilitated an impressive number of study permits. In 2021, there were 445,776 study permit holders coming into the country, many of whom will become permanent residents once their studies are complete.[16]

This level of migration is not new for the country. Canada has been in the top ten countries for international migrants for the last 60 years.[17] This level of migration is, in large part, because Canada is an attractive place for those looking to build a new life. It offers: numerous avenues for immigration—there are 14 different types of federal and provincial immigration pathways designed to encourage a wide variety of skills, individuals and needs; great job opportunities for those looking for specific roles or who are interested in taking advantage of the education to job pathways available; a highly educated population—it has the highest percentage of 25–64 year olds nationally with tertiary education, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD);[18] and a strong and vibrant immigrant community of about 250 different ethnic origins that can serve as a built-in support system to newly arrived immigrants.[19] Canada was also ranked as the most accepting country in the world for immigrants in 2019, according to a Gallup poll.[20]

But immigration is not only beneficial for Canada as the host country. Origin countries also benefit, primarily from remittances sent back by émigrés, and these numbers are not inconsequential. Official remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries were expected to reach nearly US$630 billion in 2022, which is the largest source of external finance for these countries (exceeding official development aid and foreign direct investment) if China is excluded from the calculation.[21] According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, one billion people worldwide are tied to remittances: 200 million migrants as senders and 800 million as recipients (assuming families of four).[22] While the money immigrants send home represents approximately 15% of their take-home pay—with most of it staying in the immigrant’s chosen country—the remittances represent as much as 60% of the income for families back in their home countries. Furthermore, fully half of all remittances are sent to rural areas, where the vast majority of the poorest and most vulnerable people live. In short, this money is a lifeline for families, helping them to afford food, clothing, education and other necessities and building economic resilience.[23] Separately, there is some preliminary evidence suggesting that remittances have a mild positive impact on origin countries’ GDP growth,[24] enhanced trade and foreign direct investment linked to immigrants[25] and enhanced economic opportunities and human capital gain from returning immigrants,[26] though this research is far more limited. Nearly half of all immigrants to Canada in 2021 were from five countries—India, the Philippines, China, Syria and Nigeria[27]—and the benefits of immigration are an important part of the economic strategy for these and other countries, as the following statistics reveal:

- Remittances to India have been increasing since the early 1990s, and the country was estimated to receive US$89 billion in remittances in 2021,[28] accounting for just above 3% of India’s 2021 GDP.[29] India has built a significant infrastructure by which to maximise the benefits of immigration by strengthening ties between the origin country and its diaspora through economic, educational and political avenues. It has also done so by preparing its citizens for immigration and return, including by facilitating travel for immigrants and their families, encouraging trade and commerce through preferential tax structures and incentives, easing foreign currency flow to encourage returning immigrants to set up businesses back in India and encouraging the transfer of skills gained in the destination country through foreign qualification recognition in highly sought-after sectors, such as IT.[30]

- Nigeria received nearly US$21 billion in formal remittance flow in 2021—over four times what the next highest remittance-receiving country in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) received[31] that same year, accounting for 4.4% of the country’s GDP.[32] Informal remittance flows are estimated to be about 50% larger than those recorded in formal channels.[33] With its large and growing population and an unemployment rate that increased more than 30% between 2010 and 2020 for Nigerians with secondary and post-secondary education,[34] Nigeria will need 30 million new jobs by 2030 to keep unemployment at current levels.[35] And considerable interest exists among young Nigerians to further their studies in countries such as Canada as a means of attaining postgraduate qualifications.[36] Given this, the international migration of educated individuals serves both as a way of generating remittances for families and the country at large while also easing the substantial labour pressures the country is experiencing.[37] Nigeria has identified the diaspora as an important means for rapid development and is beginning to put in place the policies and infrastructure needed to support this development, including the standup of the Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM), a body set up by the National Assembly “for the purpose of utilising the human capital and material resources of Nigerians in Diaspora towards the overall socio-economic, cultural and political development of Nigeria and for related matters.”[38] There are also other more informal migrant-related organisations, but overall, Nigeria’s interaction with its global diaspora will require a concerted and strategic plan with significant investment in order to achieve the country’s goals around immigration.[39]

But Canada’s current immigration model is sub-optimal, potentially challenging the country’s ability to recruit highly skilled international workers and thereby limiting growth in key industries, which would have a negative impact on the long-term economic growth of the country. The model is tilted in favour of providing benefits to Canada over immigrants and their origin countries. It also creates inefficiencies and gaps for the Canadian economy and diminishes the intellectual core of origin countries’ economic growth and development. The model potentially leaves immigrants disillusioned by the promise of a better life in Canada, which could lead to an erosion of Canada’s reputation as a top destination for immigrants. The following three challenges, in particular, are among the most pernicious:

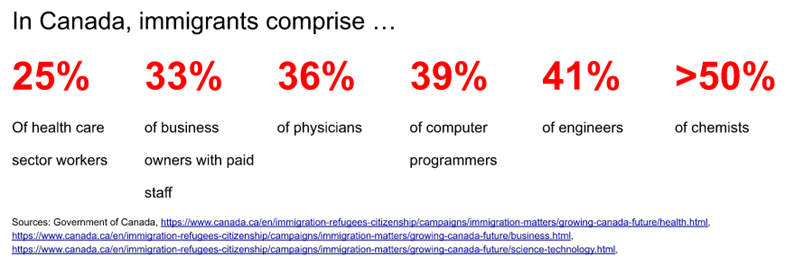

- Underemployment and under-utilisation of immigrants’ skill sets. Economic immigrants in Canada are among the most highly educated cohort. Those aged 25–54 hold 49% of all doctorates in Canada and 40% of the master’s degrees, despite only making up 23% of the population.[40] Yet they often find it difficult, if not impossible, to receive full accreditation in Canada for the training and certifications they possess from their home countries given the number of provincial governments and regulatory bodies with responsibilities in this area. Economic immigrants have higher levels of unemployment and underemployment,[41] and lower wages than Canadian-born citizens. And immigrants only account for 38% of the growth in high-skilled employment, as opposed to 60% for Canadian-born citizens.[42] This “brain abuse” or “brain waste” can lead to increased labour market frictions for those who are unable to take full advantage of the training and skills they spent years acquiring, despite the belief and implied promise they would be fully employed in their fields upon emigrating.[43] Underemployment and unemployment also have some negative effect on the mental health of immigrants, a finding that potentially negates some of the economic benefits of immigrant labour due to lower productivity and the need to access mental health services, though more research is needed to better understand this correlation.[44,45]

- Growing socio-economic divide between immigrants and Canadian-born citizens. This employment gap has led to a wage gap between immigrants and Canadian-born citizens that has been growing steadily for the last 30 years.[46] Immigrants, despite often being more highly trained or educated, make on average 20% lower hourly earnings than Canadian-born workers,[47] according to an RBC Economics study, a difference of as much as CAD$25,000 in annual lost income.[48,49] Economically speaking, closing the gap would add anywhere from CAD$16 billion to CAD$50 billion to Canada’s GDP[50,51] and would have an immediate impact not just on the immigrants and their families in Canada, but also in the origin country as a wage increase would almost certainly lead to an increase in the amounts of the remittances being sent back.[52] While the poverty rates for both immigrants and Canadian-born citizens have declined, with the rates for immigrants dropping at a faster rate than those of Canadian-born citizens, the poverty gap between immigrants and Canadian-born citizens remains stark. In 2016, the poverty rate for immigrants who had arrived within the last five years was 2.5 times higher than for those born in Canada, a gap that diminishes over time but may not fully close.[53] This is particularly true for racialised first- and second-generation immigrants, who make significantly less income than non-racialised immigrants. The gap does appear to significantly lessen during the third generation, but more study is needed.[54] This economic asymmetry sets the basis for potential social polarisation and discontent, and can lower the trust in the institutions responsible for creating immigration policies that emphasise and prioritise immigrants with skills, education and experience.

- Diminishing ability of developing nations to build their economies due to loss of intellectual capital. Without appropriate policy stopgaps, the often-permanent loss of highly skilled individuals to high-income countries can drain origin countries of intellectual capital and institutional investment, a critical foundation for building, stabilising and innovating their economies. Three primary issues account for this loss: brain drain,[55] which, as of 2010, had tripled since 1960 and doubled since 1985 between certain high-income and low- and middle-income countries; hollowing out of the middle class, driven by the fact that highly educated individuals who tend to earn more money in the origin country immigrate at a rate two to three times higher than the rate of lower-skilled workers;[56] and the generational loss of human capital, talent and innovation, a phenomenon that has the potential for happening if immigrants do not return to their country of origin. This does, however, require further study.

The business imperative: The need for sustainable immigration exchange is acute, and businesses sit at the centre of the solution. Historically, the immigration conversation has largely been the domain of federal and provincial governments with the civil sector (NGOs, civil organisations, higher educational institutions, etc.), while the role of businesses has been largely confined to creating jobs and adhering to workplace and industry laws and regulations. But the private sector must now play a more direct and central role—and co-collaborate with the public and civil sectors—as a means of ensuring it has access to the right people, talent and skills to drive innovation, stay globally relevant and lead in its markets. This shift can help create and preserve value for businesses, but only if they put immigration at the centre of their corporate and talent strategies, rather than just as an input to those strategies.

Between 2018 and 2040, 100% of Canada’s net labour force growth (3.7 million workers) will come from immigrants and they will account for one-third of the country’s economic growth rate between 2018 and 2040.[57] A 2022 Business Council of Canada survey of 80 member companies across 20 industries reported that “employers look to the immigration system to help meet a variety of business needs, from enabling enterprise growth to increasing the diversity of their workforces. Above all, immigration helps them fill positions that would otherwise stay vacant. Of the employers that make direct use of the immigration system, four out of five say they do so to address labour shortages.”[58] And yet, 80% of respondents to the same survey stated that they were having difficulty finding the right skilled workers to grow and compete globally, leading two-thirds of these same respondents to cancel or delay major projects, and leading nearly one-third to relocate work outside of Canada. Six in ten stated they had lost revenue because of their inability to find skilled workers.[59] Since 2021, for example, skills and labour shortages in the manufacturing sector led to sales and contract losses, penalties and the postponement or cancellation of projects totalling CAD$13 billion.[60]

The Canadian tech sector, which is expected to grow 4%[61] – 5.3% in 2022 and 22.4% between 2021 and 2024,[62] is an example of an industry whose growth is vastly outpacing population growth and will depend on a strong, resilient immigration program. Saskatchewan’s tech sector alone has grown 38% since 2010 and yet its population has only grown by 13.6% during that same time.[63],[64] Similarly, Ontario and Quebec’s tech industry output makes up 75% of all the industry output for Canada.[65] Between 2016 and 2021, Toronto had the largest growth in technology talent as measured by jobs added,[66] and Quebec’s tech sector is growing 73% faster than its average economic growth rate (2008–18).[67] And yet, Toronto’s population has only grown 15% and Quebec’s has only grown 11% since 2010.[68,69]

These statistics suggest that, to succeed against these headwinds, Canadian businesses must incorporate immigration as a central component of their corporate and talent strategies. Failure to do so means companies risk losing value and market share if they are unable to hire enough people, acquire the skills they need and ensure they have a pipeline of individuals who can help the company innovate and lead in the market in the future. The following four strategies will be particularly important for companies in Canada to focus on moving forward:

- Bridging the credential divide. Skilled immigrants bring significant value and education to a workplace that can serve as a market differentiator, but they may need support to get their credentials recognised or have their skills meet Canadian standards. Taking a skills-based approach to hiring and promotion within organisations and industries, rather than a job-based approach, can widen the talent base available to a company. Supporting industry recognition of foreign credentials can support bringing in the best and brightest immigrant talent and can help drive innovation within Canada.

- Building a sustainable talent pipeline. Talent pipelines that are agile enough to keep up with technological innovation and that can develop the right people with the right skills at the right time will require that businesses actively create these pipelines over years. Building these pipelines starts by working with educational systems in Canada and in origin countries to ensure that students have the right education and opportunities to learn core competencies and functional skills. Businesses’ role in developing this pipeline can and should extend through university or trade programs and internships, creating a “cradle-to-grave” approach for talent development.

- Supporting accelerated integration. The federal government works alongside civil society organisations as well as the provincial governments to provide support services to help immigrants integrate into Canadian life. The cost is not insignificant—the 2021–22 budget for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) for immigrant settlement (including resettlement) services was nearly CAD$1.7 billion[70,71]—and helps to deliver settlement programs to new immigrants, including employment support and language training. These services are vital to immigrants’ ability to live, work and thrive in a new country, not only for themselves, but also for their families. Businesses that partner with these organisations and programs to provide pro-bono services, knowledge and financial support will directly contribute to growing the pool of talented and qualified individuals who are available to work in highly skilled jobs in their communities, helping the market begin to close the wage gap between immigrants and Canadian-born citizens.

- Investing in origin countries. Funding education and training programs in the origin countries to which immigrant workers have direct ties can help businesses begin to develop a pipeline of workers who are trained and skilled to the specifications of the company. This can include working with employees to directly transfer their skills and knowledge back to their origin country, encouraging immigrant employee entrepreneurship back in their origin country and working through official government and business channels to set up educational programs (e.g. through the origin country’s Ministry of Education), internships and apprentices, developing bilateral ties with companies in the origin countries to support employee exchanges and more.

Recommendations: There are five actions businesses can take to help improve the immigration exchange and make it beneficial for all stakeholders.

- Shift the focus from jobs to skills in hiring, training and educating for high-priority industries and jobs. In a study of “hidden workers” in the United States, United Kingdom and Germany, 88% of business owners said that qualified high-skills candidates who did not meet the exact job criteria were routinely dismissed early in the application process, and the percentage for middle-skills candidates rose to 94%.[72] This is a staggering figure and, if applicable to Canada, suggests that many of these workers are being passed over because their experience does not translate to a Canadian context, not because they are unqualified. Understanding and articulating what skills will be needed to grow and innovate in industries in the future (and not just what jobs people must have held in the past) will be a necessity, particularly as Canada becomes increasingly dependent on foreign workers who almost certainly will be coming with a different set of job experiences. It will also mean that companies will have to build explicit talent strategies that centre around recruiting and hiring foreign workers and that are underpinned by leveraging government programs and working with community-based services organisations focused on settlement services.

- Create certification and work-integrated learning pathways for your business and in your industry. These “learning-to-earning” pathways are roadmaps that outline the skills, training and certifications needed for specific careers and jobs. They clearly outline the spectrum of skills required for job and career progression and will be a vital tool to helping businesses assess the potential for all applicants, foreign- or Canadian-born, to be successful in the role. These pathways can expand the pool of qualified applicants for a job, increasing the diversity of the candidate pool and, potentially, the workforce. They also provide a transparent and defensible means by which immigrants can understand how to acquire the skills they want or use the skills they have, avoiding underemployment and brain waste. By creating these pathways for their organisation, and also for key industries, the private sector can begin to move toward a skills-based, rather than duties-based, approach for hiring and promotion. For multinationals, this can mean working with subsidiaries and affiliates to build pathways that meet Canadian standards, fostering longer-term talent pools and mitigating dependency on a specific country’s labour force. Germany’s MySkills assessment tool provides immigrants without skills certifications the opportunity to demonstrate the skills they have acquired (but for which they do not have formal documentation) in 30 career paths. Through a series of online tests and assessments, immigrants can demonstrate skills competence through a certified, vetted mechanism, providing employers and immigrants with the necessary assurance and support each one needs.

- Co-create skills-centred curricula and courses with governments and educational institutions. Businesses can work with governments and educational institutions, both in Canada and in origin countries, to help fund schools, create curricula and courses that teach the technical and soft skills that employers will need in the future and provide needed technologies. Such partnerships ensure that businesses have a steady pipeline of qualified graduates, regardless of their origin country, and help strengthen ties between the two countries. Additional “add-on” programs could then be provided to support the education and skilling training, including creating a direct line to jobs in Canada to get post-educational on-the-job training, providing students in origin countries with skills and educational training that is recognised in Canada and giving Canadian businesses primary access to students who have the skills and education they need to be successful in Canada. Internships and co-op placements with explicit integration (e.g. language, soft skills) and credential acquisition are essential elements. Language training is one such program that is particularly important to implement as poor or sub-par language skills have been one of the clearest determinants of lower wages and underemployment.[73] According to one study in the United States, 25% of underemployed immigrants are potentially capable of being fully employed with some modest levels of employment-specific language training.[74] Technical training, such as software development and coding, are other examples. This type of co-operation is seen in the Skills Mobility Partnerships (SMPs) that have been set up between some European countries and origin countries as a sustainable means of skills development and mobility that creates a “quadruple-win” for the origin and host countries, the immigrants and the private sector. SMPs generally have five components to them: formalised state co-operation, multi-stakeholder involvement, training, skills recognition and mobility/migration.

- Rethink the incentives package. Expanding incentives for current and future employees is a differentiator. Interest-free loans or grants for credentials or advanced learning, access to subsidised language training and facilitated support (e.g. the Atlantic Immigration Program) will all differentiate businesses as a prospective employer and increase the success of employees while reducing onerous costs to students and experienced immigrants.

- Participate in or help stand up national and provincial “skills marketplaces.” Canadian businesses can help participate in virtual skills and jobs marketplaces that match up skills-learning opportunities with individuals seeking those skills in a way that is more flexible and efficient than what currently exists. Reminiscent of an electronic job board paired with a learning pathway, these marketplaces showcase opportunities for immigrants, from free digital courses to internships and jobs within Canada or with Canadian businesses operating in the origin country. A large part of the success of this type of “skills marketplace” will come from the private sector working with federal and provincial authorities to expedite the stand up of a Trusted Employer Program, as laid out in the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada mandate letter from the Prime Minister,[75] to expedite the hiring of temporary foreign workers by simplifying the renewals of permits, decreasing current processing times and setting up employer hotlines. The Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia is a prime example of this type of provincially based program that offers free services, including language and cultural training, job matching, access to community resources and more. The Rural and Northern Immigrant Pilot program is another such provincial program.

- Increase the number of internships, co-ops and mentorships. Immigrants are frequently required to have Canadian work experience in order to find a job in Canada yet cannot get a job without having former experience. Internships and co-ops provide a way to overcome this barrier and provide immigrants with easily recognizable experience in later credential assessments by other employers. The federal government currently offers the Federal Internship for Newcomers Program, but this is offered to a small number of immigrants and is limited to roles in the public sector. A similar program could be initiated to pair private sector employers with new immigrants or university students looking for roles, especially if done through an existing immigration career support service such as BC JobConnect or Windmill Microlending.

2. Create and fast-track foreign certification accreditation bodies and processes. Canada announced in early December 2022 a call for proposals to help create a credential-recognition program for internationally educated health-care professionals, citing the shortage of health-care workers in the country.[76] This is an excellent, and sorely needed, step that creates a rigorous, transparent and defendable process for skills certification and credential transfer/recognition. And this step will go a long way toward addressing the massive loss of intellectual capital to both the origin country (from the emigration) and Canada (from the inability to work in their field because of lack of recognised credentials), particularly in high-skill fields. The redistribution of doctors from Nigeria to Canada is a particularly pointed example of this. Canada has noted a four-fold increase in doctors from Nigeria practising in Canada,[77] while Nigeria’s doctor-to-patient ratio is 4:10,000, vastly under the World Health Organization’s recommended ratio of 1:600.[78]

Businesses should (and do) play a role in improving the current plan in the following five ways: pushing to expand this accreditation program (quickly) to other critical national industries, including technology; ensuring that businesses are helping create the accreditation standards for their industries and reimaging credential requirements in STEM sectors; pushing for the accreditation standards to be nationally recognised, rather than provincially recognised; working with Canadian and origin country educational institutions and regulatory bodies to “future proof” credentials in anticipation of immigration to Canada; and providing support for migrants to study for and take accreditation exams. This should happen, in large part, by working through existing channels with the provinces, territories and regulatory bodies—one of the mandates set forth in the Prime Minister’s mandate letter to the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.[79]

It would also be beneficial to align these new international accreditation standards with the governments of the countries from which most of the highly skilled professionals come, both early on and during the accreditation development process, if possible. By aligning with foreign governments, Canada has the opportunity to work with them to prepare their highly skilled workforce for international certification by creating training and education curricula for certain career paths, working with foreign testing boards to ensure appropriate testing and certification standards are being met and more.

- Create module-style accreditation bridging programs. Bridging programs test immigrants’ theoretical and practical field knowledge and other job-specific abilities and are an important component of international accreditation. Modules are developed in blocks so the level of skill can be accurately assessed by employers and accreditation bodies and so immigrants need to take only what is necessary to be brought to Canadian standards, avoiding duplication and high costs. Such programs are beneficial for both skilled and unskilled worker accreditation. For skilled workers, the program can prioritise technical skills accreditation for jobs in the in-demand sectors, where the program, which consists of accreditation testing and entry-to-practice requirements development, is paid for jointly by the federal and provincial governments and their employers. For unskilled workers, this system assists immigrants in gaining in-demand trade skills via apprenticeships as well as soft skills including language training and cultural acclimation to assist them in their integration into Canadian workplaces more quickly and evenly. Federal and provincial governments, employers and civil society organisations can support the cost of this training. Examples of such bridging programs already in place include The University of Toronto’s International Pharmacy Graduate program, the Bridge to Canadian Nursing program and the Ontario Bridge Training program (cross-industry).

3. Reimagine how circular migration and remittance support work. Circular migration—immigrants’ regular travel between their chosen and origin country—is an important means by which immigrants can share the skills and expertise they have gained, as well as strengthen ties and serve as unofficial “ambassadors” with their home country. When they return home, particularly for an extended period of time, the transfer of knowledge and money that occurs can help replenish the origin country’s intellectual and economic capital. In other words, the immigration model becomes additive as it becomes “brain circulation,”[80] rather than brain drain. This regular migration also potentially creates pathways for foreign direct investment into the origin country by businesses and greater trade among the origin and receiving countries.

- Establish programs or incentives for employed immigrants to return to their origin country for extended periods of time. Creating opportunities for immigrants to return home regularly to teach, support the opening of a new branch of the business in that country, do pro-bono skills training or other activities helps establish the transfer of knowledge, skills and money gained while in Canada back to their home country. These types of activities are also beneficial to the company or organisation by helping to establish or grow footholds in other global markets, establishing a presence and building trust within those local communities. They can also encourage wider-scale foreign direct investment in, and trade with, the origin country.

- Encourage the establishment of bilateral labour migration agreements (BLMAs or BLAs) between the Canadian federal and provincial governments and origin countries to oversee policies directly related to safe immigration between Canada and primary origin countries. This can include establishing bilateral preferential labour agreements, fair labour practice transparency solutions, setting up labour attachés in Nigerian embassies and consulates and more.[81] Canada has set up several of these BLMAs, including between the Government of Manitoba and the Philippines, and the Government of Canada and Honduras, and these can be used by other provincial governments as templates for more BLMAs.[82]

4. Provide social support to diasporas and immigrant communities in Canada. Support to new immigrants such as childcare, transportation services, medical and dental healthcare and more is currently the purview of the diaspora communities and provincial governments. Yet this type of support is critical to helping immigrants enter and integrate into the workforce. Private-sector support for these activities, such as providing daycare benefits, language training, creating an office within human resources that could support newly arrived immigrant employees with integration support, providing social and cultural mentors to employees newly arrived from their origin country and other similar examples, would allow immigrants and their families to better take advantage of job and training opportunities that are available.

5. Encourage immigrant entrepreneurship in Canada. Immigrants in Canada are more likely to start their own business or be self-employed, or own a privately incorporated business that provides jobs for others, than native born Canadians,[83,84] though research suggests that some immigrants who are self-employed in Canada have done so in part because of a lack of suitable paying jobs.[85] However, young immigrants in particular often have the penchant, drive and the skills needed to create early stage businesses that could bring diversity in skills, services and products to Canada. In Nigeria, for example, entrepreneurs form the backbone of the Nigerian economy: 50% of Nigeria’s GDP comes from micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), make up 85% of the total employment in the country and are found in all sectors of the economy, while 67% of all entrepreneurs are between the ages of 18 and 35.[86] Creating a more robust infrastructure to specifically and easily support young immigrant entrepreneurs could create more diverse, vibrant sectors and bring a wealth of additional skills to Canada. While there is a specific immigration entryway for entrepreneurs in Canada (the start-up visa), this requires immigrant entrepreneurs to have acquired a minimum of CAD$200,000 in venture capital funding ahead of applying and being able to enter Canada. There is a need in the community for entrepreneurial financial and educational support to those who are early on in the process of creating and establishing their own business venture and who do not have access to the venture capital or angel funds that more established ideas or businesses have. This presents an opportunity for companies to partner with local civil sector organisations to provide small loans to potential immigrant entrepreneurs already within Canada, particularly those in STEM fields, helping to build a grassroots network of small startups and innovation companies that could help drive Canada’s leadership in any number of tech or science fields. One notable example of such a program is the Chamber of Commerce in Bogotá, Colombia which provides training and support for Venezuelan refugees through its Productive Migration program. Since 2019, the program has benefited more than 160 micro and small enterprises, of which 69% increased their sales, 10% maintained them and 73% accessed the financial system to improve their business.

Conclusion: Canada has a unique opportunity to address one of the world’s most pressing issues: the skills and talent mismatch that is occurring between countries with ageing populations that need skills and talent, and those countries that are facing a burgeoning labour and skills overage, but don’t have enough jobs. Doing so fairly for all stakeholders involved can help lead to a rebalancing of current global inequity, allowing countries to gain the skills they need without it coming at the expense of origin countries and immigrants themselves. But this can only happen if businesses work alongside governments and civil society organisations. The private sector is the stakeholder best suited to identifying what jobs will be needed to grow industries in the future, the skills needed for those jobs and the appropriate education, training and certifications needed. Businesses will be the ones providing jobs, skills and training to current and prospective employees and, potentially, can also provide foreign direct investment to build educational and job pipelines in the origin countries. The future of equitable immigration exchange—the driver for economic growth and industrial innovation in Canada—sits squarely in the laps of businesses.

Footnotes

[1] Statista, “Number of immigrants in Canada from 2000-2022.” Statista Research Department, 25 October 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/443063/number-of-immigrants-in-canada/

[2] The Conference Board of Canada. “Why is immigration important to Canada?.” 8 June 2020, https://www.conferenceboard.ca/focus-areas/immigration/why-is-immigration-important-to-canada

[3] Government of Canada. “An Immigration Plan to Grow the Economy.” 1 November 2022,

[4] Thevenot, Shelby. “Canada sees record-low fertility rates same year as record-breaking immigration levels.” CIC News, 2 November 2020, https://www.cicnews.com/2020/11/canada-sees-record-low-fertility-rates-same-year-as-record-breaking-immigration-levels-1116180.html#gs.qpm2sg

[5] Government of Canada. “CIMM – Economic Immigration Pathways – March 10, 2021.” https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/committees/cimm-mar-10-2021/cimm-economic-immigration-pathways-mar-10-2021.html

[6] The Conference Board of Canada. “Why is immigration important to Canada?.” 8 June 2020, https://www.conferenceboard.ca/focus-areas/immigration/why-is-immigration-important-to-canada

[7] Government of Canada. “CIMM – Economic Immigration Pathways – March 10, 2021.” https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/committees/cimm-mar-10-2021/cimm-economic-immigration-pathways-mar-10-2021.html

[8] Government of Canada. “An Immigration Plan to Grow the Economy.” 1 November 2022,

[9] PwC Canada. “2022 Federal Budget Analysis.” https://www.pwc.com/ca/en/services/tax/budgets/2022/federal-budget-analysis.html

[10] Government of Canada. “CIMM-Budget 2022-May 12,2022.” https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/committees/cimm-may-12-2022/budget-2022.html

[11] This report focuses on economic migrants and university students who are eligible to work in Canada post graduation. For the purposes of this analysis alone, economic migrants are defined as those who are moving to Canada for economic reasons and who are following the prescribed process for immigration.

[12] Government of Canada. “Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2022-2024 Immigration Levels Plan.” 14 February 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/notices/supplementary-immigration-levels-2022-2024.html

[13] Government of Canada. “Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan.” 1 November 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/notices/supplementary-immigration-levels-2023-2025.html.

[14] Robitaille, Edana and El-Assal, Kareem. “Canada to welcome 500,000 new immigrants in 2025.” 7 November 2022, https://www.cicnews.com/2022/11/canada-immigration-levels-plan-2023-2025-1131587.html

[15] Statistics Canada. “Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians.” 26 October 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm

[16] Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. “2022 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.” Page 19, https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/publications-manuals/annual-report-2022-en.pdf

[17] International Migration Institute. “Top 25 Destinations for International Migrants.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/top-25-destinations-international-migrants

[18] OECD. “Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators.” OECD Publishing, Paris, 2022, pg. 42, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en

[19] Caleb, Marine. “Immigrant Diasporas in Canada.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2 February 2022, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/immigrant-diasporas-in-canada

[20] Esipova, Neli; Ray, Julie; and Tsabutashvili, Dato. “Canada No. 1 for Migrants, U.S. in Sixth Place.” 23 September 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/320669/canada-migrants-sixth-place.aspx

[21] Broom, David. “Migrant workers sent home almost $800 billion in 2022. Which countries are the biggest recipients?” World Economic Forum, Centre for the New Economy and Society, 2 February 2023, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/remittances-money-world-bank/

[22] International Fund for Agricultural Development. “12 reasons why remittances are important.” 15 June 2022, https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/-/12-reasons-why-remittances-are-important

[23] Ibid.

[24] Francois, John Nana; Ahmad, Nazneen; Keinsley, Andrew; and Nti-Addae, Akwasi. “Remittances Increase GDP with Potential Differential Impacts Across Countries.” World Bank blog, 16 April 2022, https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/remittances-increase-gdp-potential-differential-impacts-across-countries

[25]Koczan, Zsoka; Peri, Giovanni; Pinat, Magali; and Rozhkov, Dmitriy. “The Impact of International Migration on Inclusive Growth: A Review.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper, Institute for Capacity Development, March 2021, pg. 22, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2021/English/wpiea2021088-print-pdf.ashx (download link)

[26]Wahba, J. “Who benefits from return migration to developing countries?” IZA World of Labor 2021: 123 doi: 10.15185/izawol.123.v2, https://wol.iza.org/articles/who-benefits-from-return-migration-to-developing-countries/long

[27] Statistics Canada. “Nearly one in five recent immigrants were born in India, the highest proportion from a single place of birth since 1971.” Last modified 26 October 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/g-a005-eng.htm

[28] World Bank data. “Personal remittances received – (current US$) – India.” Data accessed 18 January 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.CD.DT?end=2021&locations=IN&start=1990

[29] World Bank data. “GDP (Current US$) – India.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=IN

[30] Balaji, Aishu. “Elite return immigration and development in India.” London School of Economics blog, 28 August 2018, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2018/08/28/elite-return-migration-and-development-in-india/

[31] Ratha, Dilip; Eung Ju Kim; Sonia Plaza; Elliott J Riordan; Vandana Chandra; and William Shaw. 2022. “Migration and Development Brief 37: Remittances Brave Global Headwinds. Special Focus: Climate Migration.” November 2022, pg. 53, KNOMAD-World Bank, Washington, DC. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/migration-and-development-brief-37-remittances-brave-global-headwinds-special-focus-climate-migration-november-2022-enarruzh

[32] World Bank data. “Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Nigeria.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=NG

[33] Ratha, Dilip. “Remittances: funds for the folks back home.” International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/76-remittances.htm

[34] Samik Adhikari, Sarang Chaudhary, and Nkechi Linda Ekeator. 2021. “Of Roads Less Travelled: Assessing the Potential of Economic Migration to Provide Overseas Jobs for Nigeria’s Youth.” World Bank, Washington, DC. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO, pg. 4, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/727521626087761384/pdf/Of-Roads-Less-Traveled-Assessing-the-Potential-of-Economic-Migration-to-Provide-Overseas-Jobs-for-Nigeria-s-Youth.pdf

[35] Adhikari, Samik and Dempster, Helen. “Using regularized labor migration to promote Nigeria’s development aims.” World Bank Blog, 23 October 2019, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/using-regularized-labor-migration-promote-nigerias-development-aims

[36] “Nigeria Market Sentiments and Study Motivations Report 2022.” https://viveafrica.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/NIGERIA-MARKET-SENTIMENTS-AND-STUDY-MOTIVATIONS-REPORT-2022-1.pdf

[37]Adhikari, Samik; Sarang Chaudhary; and Nkechi Linda Ekeator. 2021. “Of Roads Less Travelled: Assessing the Potential of Economic Migration to Provide Overseas Jobs for Nigeria’s Youth.” World Bank, Washington, DC. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO, pg. 4, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/727521626087761384/pdf/Of-Roads-Less-Traveled-Assessing-the-Potential-of-Economic-Migration-to-Provide-Overseas-Jobs-for-Nigeria-s-Youth.pdf

[38] Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NIDCOM). About Nigerians in Diaspora Commission, https://nidcom.gov.ng/about-nidcom/#1559379826255-ad301c80-6e77

[39] Federal Republic of Nigeria. “National Diaspora Policy 2021.” International Organisation for Migration, p. 16, https://nidcom.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NATIONAL-DIASPORA-POLICY-2021.pdf

[40] Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council. “Immigrant employment facts and figures.” https://triec.ca/about-us/focus-on-immigrant-employment/

[41] Talati, Shlok. “Unemployment numbers still the worst for recent immigrants.” 10 February 2023, New Canadian Media, https://newcanadianmedia.ca/unemployment-numbers-still-the-worst-for-recent-immigrants-despite-being-skilled-workers/#:~:text=Even%20at%20a%20time%20of,Ontario%20having%20the%20highest%20disparity.

[42] Hou, Feng; Lu Yao; and Schimmele, Christoph. “Recent Trends in Over-education by Immigration Status.” Statistics Canada, Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, 11F0019M No. 436, 13 December 2019,

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2019024-eng.htm

[43] Bauder, Harald. “‘Brain abuse’ or the devaluation of immigrant labor in Canada.” Antipode, November 2003, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229747500_Brain_Abuse_or_the_Devaluation_of_Immigrant_Labour_in_Canada. DOI: 10.1046/j.1467-8330.2003.00346.x

[44] Dinc, Yilmaz. “Mental Health of Newcomers: Revisiting the Influence of Work.” Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council, 10 October 2018, https://triec.ca/mental-health-of-newcomers-revisiting-the-influence-of-work/

[45] Salami, Dr. Bukola et al. “Non-Immigrants in Canada: Evidence from the Canadian Health Measures Survey and Service Provider Interviews in Alberta.” 4 April 2017, https://policywise.com/wp-content/uploads/resources/2017/04/2017-04APR-27-Scientific-Report-15SM-SalamiHegadoren.pdf

[46] RBC Economics. “Untapped Potential: Canada Needs to Close Its Immigrant Wage Gap.” 18 September 2019,

https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/untapped-potential-canada-needs-to-close-its-immigrant-wage-gap/

[47] While immigrants generally make less than their Canadian-born counterparts, there are differences in how big the wage gap is with business, finance, and management occupations having significantly smaller wage gaps than occupations in manufacturing, trades, transportation and agriculture. Natural and applied sciences was the one industry studied where there does not appear to be an immigrant wage gap. Agopsowicz, Andrew; Billy-Ochieng, Rannella. “Untapped Potential: Canada needs to close its immigrant wage gap.” https://www.rbccm.com/assets/rbccm/docs/news/2019/untapped-potential.pdf

[48] The Conference Board of Canada. “Immigrant Wage Gap.” April 2017, https://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/provincial/society/immigrant-gap.aspx

[49] Young, Rebekah. “Highly educated newcomers in Canada.” Scotiabank, 25 August 2022, https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.insights-views.immigration-skills-mismatch–august-25–2022-.html

[50] RBC Economics. “Untapped Potential: Canada Needs to Close Its Immigrant Wage Gap.” 18 September 2019,

https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/untapped-potential-canada-needs-to-close-its-immigrant-wage-gap/

[51] Young, Rebekah. “Highly educated newcomers in Canada.” Scotiabank, 25 August 2022, https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.insights-views.immigration-skills-mismatch–august-25–2022-.html

[52] The calculated increase in total remittance for an immigrant working in Ontario and earning the Canadian median 2018 wage of $31,900, if they got a 10% increase and continued to send a 15% remittance to their home country, is $355 per year (or 9%). Statistics Canada “Longitudinal Immigration Database: Immigrants’ income trajectories during the initial years since admission.” 6 December 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/211206/dq211206b-eng.htm, EES Financial, “Personal Income Tax Calculator,” 2022 https://www.ees-financial.com/img/uploads/Tax-Take-Home-Pay-Calculator-for-2022.htm

[53] Statistics Canada. “Disaggregated trends in poverty from the 2021 Census of Population.” 9 November 2022, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021009/98-200-X2021009-eng.cfm

[54] Block, Sheila; Galabuzi, Grace-Edward; and Tranjan, Ricardo. “Canada’s Colour Coded Income Inequality.” December 2019, pp. 14-15,https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2019/12/Canada’s%20Colour%20Coded%20Income%20Inequality.pdf

[55] For the purposes of this report, “brain drain” is defined as the “international transfer of human capital resources…mainly from the migration of highly educated individuals from developing to developed countries.”This definition comes from Docquier, F. “The brain drain from developing countries.” IZA World of Labor, 2014: 31 doi: 10.15185/izawol.31, https://wol.iza.org/articles/brain-drain-from-developing-countries/long#:~:text=Motivation,from%20developing%20to%20developed%20countries

[56] Koczan, Zsoka; Peri, Giovanni; Pinat, Magali; and Rozhkov, Dmitriy. “The Impact of International Migration on Inclusive Growth: A Review.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper, Institute for Capacity Development, March 2021, pg. 22, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2021/English/wpiea2021088-print-pdf.ashx

[57] The Conference Board of Canada. “Can’t go it alone: Immigration is key to Canada’s growth strategy.” May 2019, https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/immigration-will-shape-the-trajectory-of-canada-s-economy-822094581.html

[58] Business Council of Canada. “Canada’s immigration advantage

[59] A survey of major employers.” 24 June 2022, https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/report/canadas-immigration-advantage/

[1] Open letter from Goldy Hyder, President and CEO, Business Council of Canada, to the Honourable Sean Fraser, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, regarding the Government of Canada’s Immigration Levels Plan for 2023-2025, 14 October 2022, https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/publication/boosting-economic-immigration-to-tackle-labour-and-skill-shortages/

[60] Saba, Rose. “Canada’s economy lost nearly $13B due to labor shortage, new report shows.” The Canadian Press, 25 October 2022, https://globalnews.ca/news/9224124/canada-labour-shortage-economy-loss/

[61] Sharma, Amit. “Outlook for Canada’s Economy and Technology Markets in 2022.” IDC Canada, 10 January 2022, https://www.idc.com/ca/blog/detail?id=58375938b792eed16515

[62] “Tech Industry Outlook: What’s next for the technology sector in Canada.” BDC, January 2022, pg. 7, https://www.bdc.ca/globalassets/digizuite/34010-tech-industry-outlook-study-2022.pdf?utm_campaign=AUTO-TO-ST_TechOutlook2022-EN&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua

[63] Government of Canada. “Recruiting global tech talent to support businesses.” 30 August 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/campaigns/immigration-matters/stories/vendasta-recruiting-global-tech-talent-support-businesses-saskatoon-saskatchewan.html

[64] Statistics Canada. “Population estimates on July 1 by age and sex.” Reference period used was 2010–22. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.9&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2010&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20100101%2C20220101

[65] BDC. “Technology Industry Outlook: how changes in the economy affect Canada’s tech sector.” January 2021, pg. 4, https://www.bdc.ca/globalassets/digizuite/28336-st-outlookmfg-e2010-2.pdf?utm_campaign=Tech-Industry-Outlook-2020–download–EN&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Eloqua

[66]“Scoring Tech Talent 2022.” CBRE Research, July 2022, pg. 12, https://cbre.vo.llnwd.net/grgservices/secure/2022-Scoring-Tech-Talent.pdf?e=1681929552&h=4be7c1027c99466327369e1fa432fa02

67] Numana. “Key Figures from Quebec’s Tech Industry.” https://numana.tech/en/industry/

[68] Macrotrends, “Toronto, Canada Metro Area Population 1950-2023.” Last accessed 16 April 2023, https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/20402/toronto/population

[69] Macrotrends, “Quebec, Canada Metro Area Population 1950-2023.” Last accessed 16 April 2023, https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/20390/quebec/population

[70] El-Assal, Kareem. “IRCC’s immigrant settlement funding by province/territory for 2021-22.” CIC News, 4 October 2021, https://www.cicnews.com/2021/10/irccs-immigrant-settlement-funding-by-province-territory-for-2021-2022-1019306.html#gs.pztrl9

[71] This figure includes money allocated for provinces, territories and service providers. It also includes separate funding for Quebec, other IRCC initiatives and settlement funding.

[72] Fuller, Joseph B.; Raman, Manjari; Sage-Gavin, Eva; and Hines, Kristen. “Hidden Workers: Untapped Talent.” September 2021, p. 3, https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/research/hiddenworkers09032021.pdf

[73] The Conference Board of Canada. “Immigrant Wage Gap.” April 2017, https://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/provincial/society/immigrant-gap.aspx

[74] Batalova Jeanne and Fix, Michael. “Leaving money on the table: The persistence of brain waste among college-educated immigrants.” The Migration Policy Institute, June 2021, pg. 10, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/mpi-brain-waste-analysis-june2021-final.pdf

[75] Office of the Prime Minister, Canada. “Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Mandate Letter.” 16 December 2021, https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2021/12/16/minister-immigration-refugees-and-citizenship-mandate-letter

[76] Government of Canada, “Government of Canada launches call for proposals to help internationally educated professionals work in Canadian healthcare.” 5 December 2022,

[77] Adepoju, Paul. “Nigeria’s medical brain drain.” Devex, 20 November 2018, https://www.devex.com/news/nigeria-s-medical-brain-drain-93837

[78] Fatunmole, Marcus. “Four doctors to 10,000 population, Nigeria’s highest in two decades – Data.” International Centre for Investigative Reporting, 17 March 2022, https://www.icirnigeria.org/four-doctors-to-10000-population-nigerias-highest-in-two-decades-data/

[79] Office of the Prime Minister, Canada. “Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Mandate Letter.” 16 December 2021, https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2021/12/16/minister-immigration-refugees-and-citizenship-mandate-letter

[80] United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. “Defining and Measuring Circular Migration.” 20 January 2016, https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/bur/2016/February/14-Add1_Circular_migration.pdf

[81] Adhikari, Samik; Sarang Chaudhary; and Nkechi Linda Ekeator. 2021. “Of Roads Less Travelled: Assessing the Potential of Economic Migration to Provide Overseas Jobs for Nigeria’s Youth.” World Bank, Washington, DC. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO, pg. 14, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/727521626087761384/pdf/Of-Roads-Less-Traveled-Assessing-the-Potential-of-Economic-Migration-to-Provide-Overseas-Jobs-for-Nigeria-s-Youth.pdf

[82] United Nations Network on Migration, “Guidance on Bilateral Labour Migration Agreements.” February 2022, https://migrationnetwork.un.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl416/files/resources_files/blma_guidance_final.pdf

[83] Singer, Colin R. “Immigrants Start More Businesses And Refugees Are More Loyal Employees, Studies Reveal.” 3 August 2022, https://www.immigration.ca/immigrants-start-more-businesses-and-refugees-are-more-loyal-employees-studies-reveal/

[84] Statistics Canada, “Immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada: Highlights from recent studies.” 22 September 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/36-28-0001/2021009/article/00001-eng.pdf?st=iHsDwAng

[85] Picot, Garnett and Ostrovsky, Yuri. “Immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada: Highlights from recent studies.” 22 September 2021,

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2021009/article/00001-eng.htm

[86] Adeyemi, Adenike; Nwaokolo, Amaka; Erumebor, Wilson; Obele, Gospel; Agunloye, Oyebola; and Henry, Godwin. “State of entrepreneurship in Nigeria, The Fate Foundation, November 2021.” The Fate Foundation, 28 October 2021, https://fatefoundation.org/download/2021soe/