The funding gap for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is still significant, amounting to US$2.5 trillion annually in developing countries. The COVID-19 pandemic has widened the gap, increasing it to $4.2 trillion annually. Therefore, the Group of 20 (G20) should create an effective blended-finance scheme that is more attractive to stakeholders, especially philanthropic donors. We recommend that the G20 should: (1) adopt and consolidate the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) DAC Blended Finance Principles and Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance; (2) develop an inclusive and attractive framework to increase the participation of philanthropic institutions; (3) promote the transparency and friendly-environment of blended finance; and (4) the F20 should take a lead role in implementing the blended finance scheme for philanthropic institutions, particularly by increasing the participation of local philanthropic institutions.

Challenge

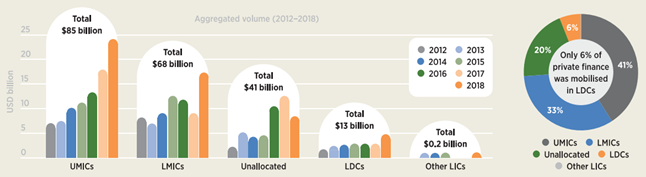

Although blended finance could become a critical step in bridging the funding gap for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), this finance is not well-mobilised. Based on Figure 1, the mobilisation of blended finance in 2012-2018 remained concentrated in upper-middle-income countries and low-middle-income countries, with over US$84 billion (41 percent) and $68 billion (33 percent), respectively (OECD, 2020a). Meanwhile, the least developed countries only received $13.4 billion (6 percent). This situation is caused by the lack of data collection, a common and harmonised framework, product standards and performance measurement regarding blended finance (IDFC, 2019). These challenges have caused difficulties in fulfilling the necessary scale and desired impact to support the achievement of the SDGs. Furthermore, previous reports from the ITF Impact Taskforce (2021) focused more on emerging markets rather than least-developed countries, co-creating this gap in mobilising private finance.

Figure 1. Mobilisation of private finance (based on income group)

Source: OECD, 2020a

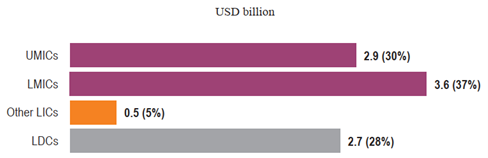

Besides that, the philanthropic flows also mainly target middle-income countries. From Figure 2, we can see that approximately 67 percent of allocable giving was directed to middle-income countries, of which 30 percent went to upper-middle-income countries and 37 percent to lower-middle-income countries. In contrast, only a third of allocable funding targeted least-developed countries (28 percent) and other low-income countries (5 percent). Furthermore, detailed information on philanthropic funding is minimal, either by donor type, use of funds or recipient country and population. This lack of detail is made worse by the lack of a universal definition and framework of data tracking and reporting across countries (Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2020)

Figure 2. Philanthropic giving (based on income group, 2013-2015)

Source: OECD, 2018c

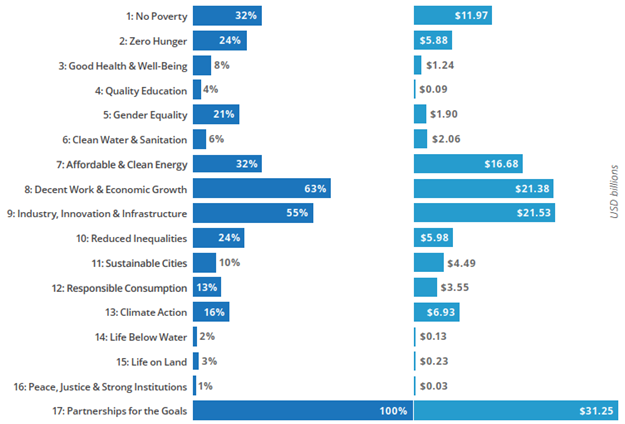

Moreover, between 2013 and 2015, approximately 45 percent of philanthropic funding was not allocated to a specific region, making it hard to track these funds (Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2020). Thus, calculating, reporting and monitoring the actual amount and development of the funding is difficult. Furthermore, the environment for blended finance is still underdeveloped, and it is not enough to attract more philanthropic funding. The transactions and implementation of blended finance also lack accountability and transparency because of insufficient information given to the public. Consequently, blended finance is not equally mobilised in all the SDG sectors. Blended finance is still highly aligned with some goals, such as Goal 17 (Partnerships for the goals) and Goal 8 (Decent work and economic growth). Meanwhile, it is less aligned with Goal 16 (Peace, justice and strong institutions) and Goal 14 (Life below water) (Convergence, 2021).

Figure 3. Proportion of SDGs’ alignment and total financing mobilized towards SDGs (2018-2020)

Source: Convergence, 2021

Furthermore, the SDG’s financial gap has become even worse during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Global Outlook (2020) on Financing for Sustainable Development, developing countries face a $1.7 trillion shortfall in the financing needed to keep them on track with the realisation of the SDGs as governments, investors and other stakeholders grapple with the economic, social and health crisis due to global pandemic (OECD, 2020a). The OECD 2020 report also noted that developing countries experienced a decline of $700 billion in external private finance and a gap of almost $1 trillion in public spending on COVID-19 recovery measures compared with what developed countries spent (OECD, 2020b). This gap occurs because developed countries have greater capacity and capability in the economy, both in borrowing and attracting investors. The decline in private financing felt by developing countries was also caused by decreased foreign direct investment, portfolio investment and remittances sent by migrant workers.

Funding for the SDGs agenda will risk collapsing disproportionately for developing countries. Both COVID-19 and the wider SDGs financial gap could cause a significant reduction in all financial resources for countries experiencing a crisis with severe structural obstacles. These issues will be the main challenges for future development progress. Thus, providing solutions and mechanisms through a more updated blended-financial scheme is crucial to closing the SDGs’ financial gap, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Proposal

Agenda 2030 requires that every person should enjoy the complete package of rights and opportunities promised by the SDGs. In order to achieve the goals while coping with the current challenges, we provide four key proposals to the G20 as follows.

1. Adopting the OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles and Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance

By adopting the OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles, blended finance can be deployed in the most effective way to assess the financial needs for sustainable development. Indeed, these principles have been embedded in international development architecture and recognised as the best practices for blended finance. According to the OECD (2021), blended finance is the strategic use of development finance to mobilise additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries. There are five principles of the OECD DAC Blended Finance; (1) anchor blended finance in a development rationale; (2) design blended finance to increase the mobilisation of commercial finance; (3) tailor blended finance to local contexts; (4) focus on effective partnering for blended finance; (5) monitor blended finance for transparency and results (OECD, 2018c).

The G20 also has referenced these principles in several presidencies. For example, in the G20 Osaka Declaration, world leaders recognised that blended-finance schemes could play a key role in upscaling collective efforts to unlock commercial finance for SDGs. Along with the Osaka declaration, the five OECD principles have also shaped the context and discussion of blended-finance policies aimed at promoting and intensifying best practices among various stakeholders such as the Group of Seven (G7), the World Economic Forum, the European Union and the UN. However, these principles should not be limited as a reference, but the G20 should also adopt and consolidate them into the G20 blended-finance scheme.

The G20 needs to adopt Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance to establish a framework for common values among all stakeholders in achieving SDGs. The Tri Hita Karana Roadmap consists of five shared values and guidelines, emphasising that coordinated action across markets is essential to create effectiveness and efficiency to provide financing and development impacts for realising the SDGs. The five shared values that are important for the Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance are; (1) anchor blended finance in the SDGs; (2) commit to using blended finance to mobilise commercial finance; (3) design blended finance to move towards commercial sustainability; (4) structure blended finance to build inclusive markets; and (5) promote transparency when engaging in blended finance (OECD, n.d).

Address the sector priorities of SDGs within least-developed countries

A “one size fits all” scheme is ineffective in implementing SDGs because each country has unique and different characteristics. For example, in small countries that rely on marine-based industries, the G20 should carry out a “blue blended finance scheme,” including blue carbon schemes, blue bonds or impact funds for ocean-based activities. Meanwhile, the G20 should create a blended-finance scheme that focuses on infrastructure development in landlocked countries.

Improve the measurement of impact

The G20 should ensure that ex-ante impact assessments and ex-post evaluations of SDGs are undertaken and available to the public. Various impacts of blended finance, especially on poor people, need to be assessed by developing a practical checklist. This has been conducted by the Tri Hita Karana Impact Working Group by providing a set of questions and screening considerations for the ex-ante assessment of the expected impact and the ex-post assessment of the actual impact (OECD, 2021). By doing this, blended finance can be given directly to the projects with the most significant impact on sustainable development.

Establish a post-COVID-19 blended finance scheme

Guided by the five principles of the OECD DAC and Tri Hita Karana Roadmap, the G20 should establish a blended-finance scheme that focuses on post-pandemic recovery. This scheme should prioritise the sector relating to job creation and economic growth of the target countries. The health sector must also be improved to strengthen national health systems. The G20 should ensure that blended finance can support countries, particularly developing countries, to achieve a more inclusive social and economic sustainable development.

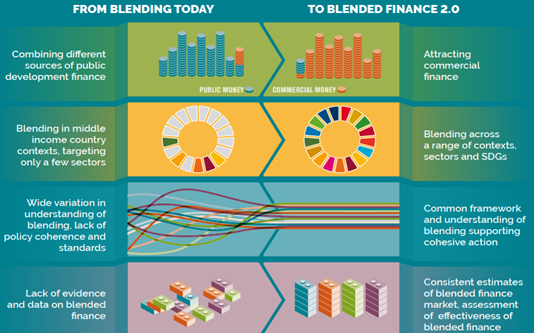

Move towards blended finance 2.0

Blended finance is an approach in the development toolbox focused on increasing SDG financing and filling the financing gap. Therefore, the G20 should improve the system towards blended finance 2.0. According to the OECD (2018b), blended finance 2.0 has four characteristics, namely (1) it begins to attract commercial financing; (2) it blends across a range of contexts and sectors of SDGs; (3) has a common framework and understanding of blending that can support cohesive action; and (4) makes a consistent estimate of the blended finance market and assessment of blended finance effectiveness.

Figure 4. Comparison between blended finance today and blended finance 2.0

Source: OECD, 2018b

2. Developing an inclusive and attractive framework for philanthropic institutions

Institutional philanthropy has a global reach, with more than 260,000 foundations in 39 countries. Foundations’ assets exceed US$1.5 trillion and are heavily concentrated in the United States and Europe. Furthermore, the amount of philanthropic contributions to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is US$31 billion. Cross-border private aid averages US$60 billion and US$70 billion annually (Callias, 2017). Thus, philanthropy is crucial in filling the SDG financial gap. We then bring five proposals to the G20 in order to develop a more inclusive and attractive framework for philanthropic institutions:

Strengthen the enabling environment for philanthropy

Philanthropy often seeks a conducive enabling environment for its funding to become efficient, effective and sustainable. An enabling environment for philanthropy should be created. Thus, it can leverage its potential to better support development. National governments should have an open-door policy for philanthropy to encourage a more connected and accountable philanthropic sector in the country. The G20 should establish a legal status that distinguishes philanthropy from civil society organisations (CSOs) or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). It would be better if each country had a specific philanthropy law. The G20 also should offer favorable tax policies, such as tax incentives, that make countries more attractive for philanthropic funding. However, countries must be careful about anti-money laundering and anti-terrorism regulations because these can indirectly discourage philanthropy.

Employ digital funding solutions

The rapid development of information and communication technology can make SDG funding faster and easier. This utilisation is essential because new digital methods are emerging as one of the key future trends for cross-border philanthropy (Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2020). Therefore, the G20 should advance the usage of crowdfunding platforms, online giving and funding through social media. By advancing these methods, the G20 could provide fast access and effective means for making charitable donations, particularly in international giving and fundraising. If more data on philanthropic giving are available online, philanthropic institutions can also learn the experiences of one another.

Promote transparency and data sharing

To improve its effectiveness, the G20 should provide better data availability on philanthropic funding and activities. Each country can share this data and information through open data networks that everyone including philanthropic institutions can access. The availability of comprehensive data should be considered as part of tracking towards development goals. It can provide insight and the basis for other philanthropic institutions to decide their priority sectors or countries that will be the funding targets. Best practices and innovative work plans should also be shared to empower all development actors, including philanthropic institutions, to achieve the same goal. Furthermore, the G20 should provide a transparent multi-stakeholder mechanism for data gathering and sharing. This mechanism could concretely review the challenges and impacts of SDG implementation.

Improve collaboration and partnership

Governments must consider philanthropic institutions as partners, not only a source of additional SDG funding. Thus, the G20 should allow deeper and sustainable collaboration between governments and philanthropic institutions. This collaboration must go beyond sharing information and good practice to establish a common strategy, unifying resources and decision-making. Furthermore, the G20 also should create dedicated philanthropic dialogue platforms between governments and philanthropic institutions, such as the Kenya Philanthropy Platform. These platforms can provide a more stable and sustainable basis for ongoing cooperation between the parties. The G20 also can take an example from the Convergence Partnership to create new standards for transformational philanthropic practices and engagement at regional and national levels.

Utilise the potential of diaspora philanthropy

Diaspora philanthropy can potentially increase the development of origin countries, destination countries and migrants. According to Espinosa (2015), a migration-development nexus has emerged as a new form of development aid that is triggered by three global trends, namely (1) the professionalisation of international labour migration; (2) the ballooning of private remittances; and (3) the decline of official development aid. Thus, the G20 should create an agenda or programme that engages migrants in related countries. A programme of action could be formed to make migrants a pivotal force in providing new development aid. The British Asian Trust can be taken as an excellent example due to its successful experience in delivering high-quality programmes in South Asia by applying a social-finance approach. One interesting task this diaspora-led international development organisation carries out is using blended finance to fund maternal, neonatal and child health care in Bangladesh.

3. Creating a friendly environment for local philanthropic institutions

Local philanthropy is a source of technical knowledge that cultivates a broader range of relations with local development parties. It plays a vital role in various countries. Local philanthropic flows represent a significant part of total philanthropic flows, such as 83 percent in Turkey, 60 percent in Mexico, and 35 percent in China (OECD, 2018). Indeed, the Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy and Give India already exist as the leaders in this field. However, they only focus on South Asia, especially Pakistan and India. Therefore, the G20 should enlarge the focus on several countries with significant local philanthropic flows, such as Turkey, Mexico and China. We then recommend the following actions be carried out by the G20.

Mapping the SDG ecosystem

The G20 should provide a better understanding of the SDGs to the local philanthropic institutions. This can be conducted by mapping the SDG ecosystem in the country or region. The map should contain the key government bodies involved in the SDGs, the method of coordination, relevant national or international policies, and information on the philanthropic institutions that have already participated in this region. This would help philanthropic institutions understand and navigate the SDG system in the country or region. It also could identify the relevant entry points for the engagement or the prioritised sectors that can be targets for funding.

In mapping the SDG ecosystem, the G20 can refer to the OECD Action Plan on the SDGs, which has four areas for action, namely (1) applying an SDG lens to the OECD’s strategies and policy tools; (2) leveraging OECD data to help analyze progress in the SDGs’ implementation; (3) upgrading the OECD’s support for integrated planning and policy-making at the country level, and providing a space for governments to share experiences about the SDGs; and (4) reflecting on the SDGs’ implication for OECD external relations (OECD, 2015).

Engaging local stakeholders

The G20 should improve collaboration space between philanthropic institutions and local stakeholders. This will provide more opportunities for them to develop strong ties and relations with individual districts or provinces within countries. Local philanthropic institutions, then, could participate more deeply in guiding local authorities towards achieving the SDGs in a particular region. Thus, in the beginning, the G20 should introduce philanthropic institutions and their importance of local stakeholders becoming more familiar with them.

Create local 2030 goals

First and foremost, the G20 should identify the most pressing challenges within a local region in a country. Using trusted data sources provided by governments, the G20 should identify the SDGs most relevant to local communities’ needs. This would enable the development of local goals or targets inappropriate to the 2030 Agenda. The number of local targets should not be excessive because fewer targets will ensure that the SDGs are contextualised and understood by the philanthropic institutions.

4. Getting the F20 to take a lead role

The Foundations Platform F20 is a network of more than 70 foundations and philanthropic organisations that calling for transnational action to achieve sustainable development. As a critical platform for philanthropic organisations within the G20, the F20 should lead in implementing the blended finance scheme for philanthropic institutions. This group should improve the participation of local philanthropic institutions in SDGs funding, not merely focusing on international collaboration. Therefore, by adding local collaboration to its main agenda, the F20 can become a catalyst to attract more local philanthropic organisations to SDGs funding. We then recommend three follow-up actions that the F20 should conduct.

Promote local collaboration

The F20 tends to focus on international collaboration, whereas local collaboration has barely a mention. However, engaging local society or stakeholders is an essential step towards achieving the 2030 Agenda. In this case, the G20 should learn from the Network of Foundations Working for Development (netWFD) and the SDG Philanthropy Platform because they have created and facilitated dialogue between philanthropic institutions, governments and local stakeholders (OECD, 2018). The dialogue could establish a multi-stakeholder partnership that focuses more on the local level. Furthermore, the F20 should be positioning itself as a vital partner in the discussion about localisation or localising SDGs, what sectors should be prioritised, and how to improve the partnership to create better outcomes.

Create specific guidelines for local engagement

To ensure that local engagement and collaboration run effectively, the F20 should create specific guidelines that contain principles, management and other relevant concepts. In this case, the F20 should take the netFWD Guidelines for Effective Philanthropic Engagement as an example. The Guidelines contain three pillars: dialogue, data and information sharing, and partnership that focuses on the country level (OECD, 2018). By referencing this, the F20 should promote mutual trust, recognition and connection between governments and philanthropic institutions at the local level. Besides that, to encourage local communities to participate in the SDGs, the F20 should increase solidarity by cherishing the values including empathy, peace, and tolerance within the society.

Global challenges, local solutions

There is a need to create innovative approaches to improve SDG funding and cope with local challenges. The F20 should learn from the Academy of Development of Philanthropy in Poland, which launched the Global Challenges Local Solutions Fund in July 2016. The Fund has proposed distributing grants, making annual grants linked to the SDGs and seeking support from local philanthropic institutions or foundations throughout Europe (Ross and Spruill, 2018). By referencing this Fund, the F20 should focus on financial inclusion and seek financial support from local philanthropic institutions within the G20 members or other parts of the world. It is the task of the F20 to collaborate with the G20 members directly and not to depend on the bureaucracy of the G20, making it more flexible while emphasising the global nature of the approaches and highlighting the local solutions.

References

Convergence, The State of Blended Finance 2021, 2021,

IDFC, Blended Finance: A Brief Overview, October 2019, pp. 18-19,

Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Global Philanthropy Tracker 2020, Indianapolis, 2020, pp. 24-43,

ITF Impact Taskforce, Time to deliver: mobilising private capital at scale for people and planet, 2021.

Karoline M. Callias, Heather Grady, and Karina Grosheva, “Philanthropy’s contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals in emerging countries,” in European Research Network on Philanthropy 8th International Conference, Copenhagen, July (2017), 4-22.

Natalie Ross and Vikki Spruill, Local Leadership, Global Impact: Community Foundations and the Sustainable Development Goals, 2018, pp. 1-29.

OECD, Better Policies for 2030: An OECD Action Plan on the Sustainable Development Goals, New York, 2015, pp. 4-9.

OECD, Blended Finance Can Help Bridge the Investment Gap for the SDGs, but Requires a Common Framework, Paris, 2018a, pp.1,

OECD, Blended Finance Guidance, Paris, 2021, pp.3,

OECD, Blended Finance in the Least Developed Countries 2020: Supporting A Resilient COVID-19 Recovery, Paris, 2020a, Ch. 1 & 2,

OECD, COVID-19 Crisis Threatens Sustainable Development Goals financing, Paris, 2020b, pp.1,

OECD, Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2021, Paris, 2020c, pp. 25-28,

OECD, Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, Paris, 2018b, pp. 15-17,

OECD, The Development Dimension: Private Philanthropy for Development, Paris, 2018c, Ch. 2 & 4,

OECD, Tri Hita Karana Roadmap for Blended Finance, Paris, n.d, pp. 1,

Shirlita A. Espinosa, “Diaspora Philanthropy: The Making of a New Development Aid?”, in Migration and Development (2015), pp. 1-17.