The record on digital inclusion is clear: women have been left behind. Within certain economies, cultures, and regions, the digital literacy gender gap prevents women from unlocking better learning opportunities and economic prospects. This policy brief measures the relationship between digital literacy gaps and sociocultural factors. It then describes why digital literacy gaps start forming in childhood and how most digital skilling programmes fail to address the obstacles women face in becoming a part of the digital world. It concludes by pinpointing solutions to these issues and urging the G20 and other countries to address the unique challenges of women’s digital literacy.

Challenge

Women lag behind men in a range of indicators associated with internet access and use. The World Wide Web Foundation found that the digital gender gap had barely improved since 2011 in lower and middle-income countries. According to the report, globally, men are 21 percent more likely to be online than women, a gap that rises to 52 percent in least developed countries. The problem with women’s access to digital resources does not reside in the medium itself but with the social context in which women are located. Factors such as lack of agency, education inequality, and digital spaces being viewed as dangerous and unsafe for women widen the gender digital gap. These barriers intersect across the supply side, demand side, as well as legal and regulatory domains. For instance, costs associated with internet use remain prohibitive across countries for both men and women. Still, women’s relatively lower access to economic resources and independence, and their relative time poverty exacerbate exclusion—particularly for older women, those living in rural areas, and those who are poorer.

Moreover, labour markets and education can further reinforce gender stereotypes about appropriate roles and jobs for women and men. In many contexts, technical and vocational education is seen as primarily a male preserve or is heavily segregated in terms of employment type (e.g., mechanics for males and hairdressing for females).

Many of these factors can be found at the regional level defined within countries and tend to persist over time. For instance, one of the most striking findings identified in the literature is that the historical roots of contemporary regional gender-specific roles (cultural factors) can sometimes be traced back to pre-industrial times, shaped by prevailing social structures (e.g., Alesina et al., 2013; Giuliano, 2018; Sorgner, 2021). Thus, local cultural factors impacting gender equality may persist even when societies transition to a more advanced stage of development.

However, national digital literacy programmes often fail to acknowledge and address these issues. As a result, the gender gap in digital skills and literacy remains a formidable barrier to girls and women benefiting from new economic opportunities, vital information such as health- related advice and guidance, and overall social and public engagement.

Digital literacy and skilling programmes run by countries thus have to be evaluated to determine whether they sufficiently address the unique challenges that women face to become a part of the digital world (Sorgner, 2019). The potential for digital gender equality is greatly enhanced as the world rapidly adopts artificial intelligence for education, technological advancement, and economic productivity. Digital literacy may unlock better learning opportunities, skills development, and economic prospects. The Indonesian presidency has identified Digital Skills

and Digital Literacy as one of the priority issues for the Digital Economy Working Group. Therefore, the complex interplay of socio-cultural factors and constraints around gender roles needs nuanced and coordinated policy responses at the global level.

Proposal

Quantifying the relationship between social norms and the gender gap in digital literacy

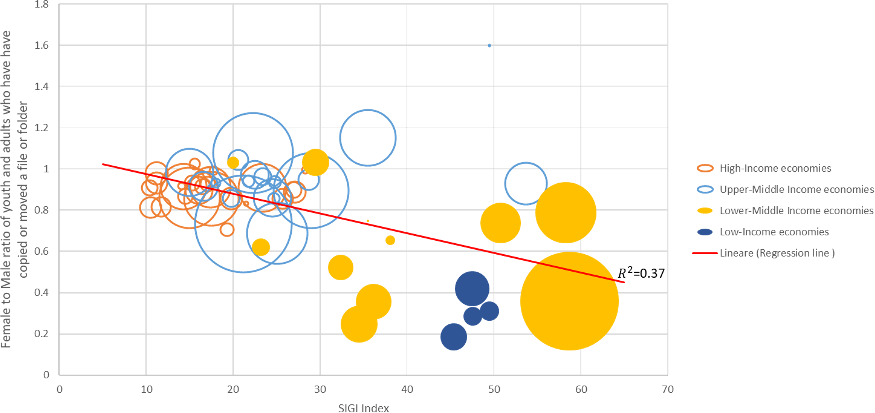

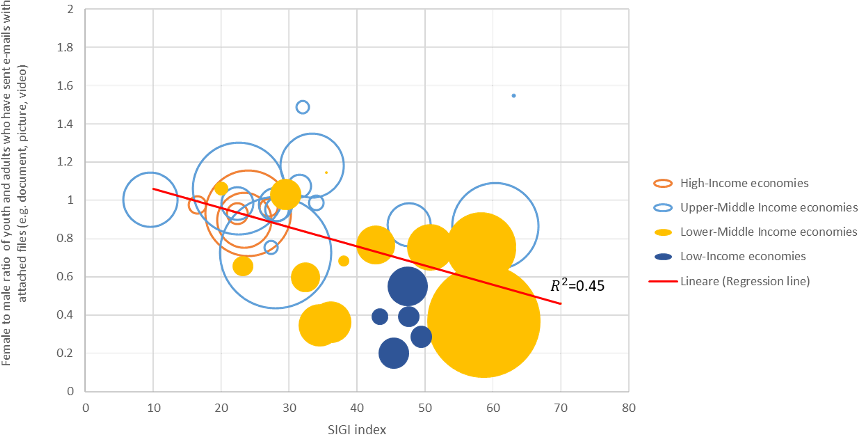

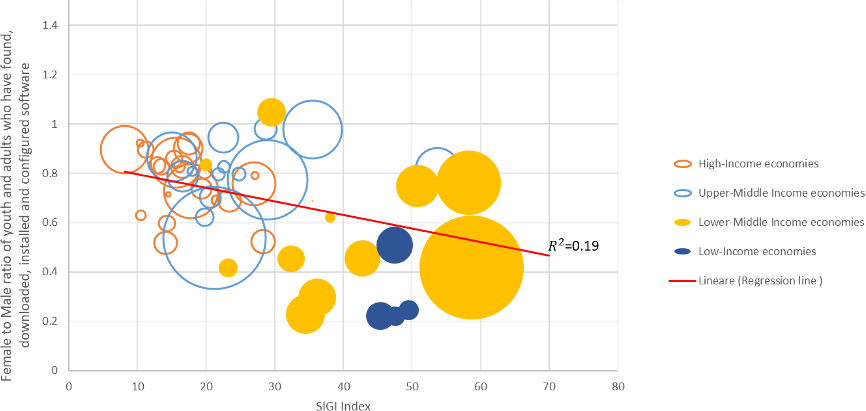

To outline the relationship between gendered social norms and gender gap in digital literacy, we have plotted the correlation between a series of indicators from Target 4.4.1 of SDG 4 on Quality Education—which measures the proportion of youth and adults with different information and communications technology (ICT) skills—and the Social Institution and Gender Index (SIGI). The SIGI is a cross-country indicator that measures the impact of social and cultural norms on women’s empowerment. The aggregate result is an index that ranges from 0 (=inclusive social and cultural norms) to 1 (=very restrictive social and cultural norms), which quantifies the level of discrimination experienced by women in every stage of their lives.

The graphs below show the correlation between selected indicators from Target 4.4.1 and the SIGI. To fit the regression line, we weighted each country for the population size (represented by the size of the bubbles) to limit the distortion of possible outliers. To quantify the gender gap in digital literacy, we used the female to male ratio obtained by dividing the percentage of women with a particular ICT skill by the percentage of men with the same skill.

For the analysis, we selected three indicators representative of the digital skills of a population that we have ranked from the most basic to the most advanced:

- Proportion of youth and adults who have copied or moved a file or folder (%).

- Proportion of youth and adults who have sent e-mails with attached files (e.g., document, picture, video).

- Proportion of youth and adults who have found, downloaded, installed, and configured software (%).

Even with some variability, most countries for all the selected indicators display a female to male ratio below 1, highlighting that women generally have lower digital skills than men. Interestingly, all the selected indicators highlight a negative correlation (ranging from a figure of 0.19 to a stunning 0.45) between the female to male ratio and the SIGI index: the higher is the level of discriminatory social norms (SIGI index close to 1), the lower is the Female to Male ratio (the percentage of women with a specific ICT skill is lower than the percentage of men).

The income levels of the countries included in the analysis appear highly predictive of discriminatory social norms and the gender divide in digital literacy. High-Income economies have more inclusive social norms (SIGI index closer to 0) and consequently have a higher female-to-male ratio (smaller gender divide) compared to Lower-Middle Income and Low-Income

economies. For the more basic skills (copy or move a file or folder, send e-mails with attached file), the High-Income economies approach a ratio equal to 1 (perfect parity). In contrast, even the most technologically developed countries lag behind in the more advanced skills (downloading, installing, and configuring software). This distinction does not appear very neat for the Lower-Middle Income and Low-Income economies, highlighting a similar gender divide in basic and advanced skills.

Age dimensions of the digital literacy gender gap

Addressing the gender gap in digital skills requires investing early in girls’ access to digital resources and STEM education (World Bank, 2021), and strengthening the digital environment that children can access safely and widely, in line with their evolving capacities across ages. While two-thirds of the world’s school-age children do not have fixed internet connection in their homes (UNICEF Office of Research, 2022), the growth of mobile subscriptions has meant many children have access to digital resources via their phones.

Disaggregated data for children’s access to digital technology is hard to come by, with most data aggregated at the household level. Within a household, a child’s access is further shaped by the extent of parental control and the sharing of devices with other siblings or household members. Data from a recent survey (UNICEF Office of Research, 2022) with over 5,000 children aged 12- 17 years in five countries of Eastern and Southern reveal barriers faced particularly by younger children, rural children, and girls. Across all countries, girls were less likely to report being internet users than boys. In particular, and across all countries, girls were more likely than boys to report being prevented from access to the internet by parents and, to a lesser extent, teachers.

Social control of girls’ digital access is dependent on the wider social norms that construct degrees of mobility and independence for girls and women. The decision to purchase a phone, as well as which handset to purchase, is often not independently made by women but by husbands or other male authority figures (GSMA, 2015); furthermore, there are often barriers to recharging credit if it entails going to a shop to do so. Mobility constraints are likely to be more experienced by girls than women, especially adolescent girls. A particular concern in more socially conservative societies is the freedom that having phones may grant girls to pursue romantic interests outside of the framework of marriage—often more based on perception or fear than actual occurrence.

Digital literacy programmes’ common flaws

Having established a gender gap in digital skills, especially in developing and low-income countries, and its early-age origin, we now bring focus to the role of digital literacy programmes in addressing this wedge. Digital skills are not usually a part of school curriculums, limiting the capabilities of the marginalised to effectively and equally participate in the digital world. This usually includes women and girls.

This section seeks to analyse digital literacy programmes through the lens of gender. The goal is to assess whether they are designed to address cultural and social constraints that women experience or if they lead to further systematic discrimination and unequal outcomes for women in the digital ecosystem. We present an analysis of digital literacy programs across countries (refer to Table 1) to illustrate varying approaches adopted by governments to build digital skills.

We find that at least several countries have gender focus built into their digital literacy initiative, though none, barring the EU, place official targets or actually track progress.

Table 1.

| Country | National digital literacy policy | Objective of the Programme | Women listed as target beneficiaries | Official targets for women | Gender disaggregated data collected (to track progress) |

| India | Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta. Abhiyaan (PMGDISHA) | To make one person in every eligible rural family digitally literate. | Yes | No | No |

| Indonesia | Makin Cakap Digital | To accelerate digital transformation, build knowledge and public awareness, and develop digital skills. | No | No | No |

| Republic of Korea | Baeumnara | To provide e- learning to major underserved groups including the elderly, the disabled, housewives, and low-income earners. | Yes | No | No |

| Saudi Arabia | Attaa Digital | To spread digital literacy and awareness | Yes | No | No |

| Kenya | DigiSchool: The Digital Literacy Programme | Integrate use of digital technologies in learning | No | No | No |

| Canada | The Digital Literacy Exchange program | Encourage participation of underrepresented groups in the digital economy by investing in initiatives that provide them with necessary digital tools, access, and skills development opportunities. | No | No | No |

| European Union | Digital Education Action Plan (2021-2027) | Prioritise fostering the development of a high-performing digital education ecosystem and enhancing digital skills and competencies for the digital transformation | Yes (Action 13) | Yes | Yes |

The assessment of these literacy programmes highlights four key challenges:

- Most digital literacy programmes fail to address women’s social and cultural challenges, especially in developing countries. The lack of agency, paternalistic attitudes, and controlled access to online spaces limit the ability of women to engage meaningfully in the digital ecosystem. But only a few programmes take into account this problem. The Internet Saathi program launched by the Tata Trust for rural women in India provides an excellent model for addressing this challenge where digitally trained women train other women, contributing to a growing network of digitally skilled women in rural areas.

- The design of digital literacy programmes fails to define specific targets to reduce the gender gap. While India’s PMGDISHA states that women candidates will be given preference, it has no gender-specific targets. Such literacy initiatives can widen the gender gap in digital adoption and use. Indeed, the eligible households can nominate one person from their family to enroll in this programme, and for reasons described in this policy brief, families tend to appoint their sons rather than daughters. Specifying targets, as placed by the EU for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) education of female students, have resulted in a progressive change in the education and employment of women. Similarly, the Republic of Korea placed focus on the training of working women, who were forced to operate from home during the Covid-19 outbreak to fulfil care responsibilities. Targeted and monitored initiatives yield better outcomes than loose statements on a desired objective.

- Digital literacy programmes, as highlighted above, fail to address the systemic gender gap in education and consequently digital literacy. Several countries have tried to integrate digital skills in the K-12 education curriculum. Saudi Arabia has recognised digital literacy as a “basic skill” alongside numeracy and literacy under its Human Capability Development Program Delivery Plan under vision 2030. Kenya’s Digital Literacy Programme is also a major undertaking that seeks to integrate ICTs across all levels of education in a phased manner. However, gender biases—in society, within families, by instructors and policy makers—continue to act as obstacles, preventing women from accessing or completing formal education, which also spill into a lack of digital skills.

- Digital literacy programmes are often inadequate in providing a complete understanding of online experiences. Meaningful engagement in the digital world is much more than watching video content or exchanging messages on social media. Most digital literacy programmes are limited in what they offer and mostly comprise training to operate devices, exchange emails, access e-government services, and pay digitally. Crucial elements of online safety, cyber security, and privacy are beyond the scope of these literacy programmes. Indonesia’s Makin Cakap Digital is a good example of a programme that holds widespread interactive digital literacy classes centred around Safe and Ethical Digital Media, Digital Media Proficiency, and Digital Media Culture.

Policy Recommendations

Create a safer online space for women

The internet being viewed as an unsafe space for girls and women leads to limiting factors such as lack of agency and lack of or limited and controlled access to online spaces. Digital literacy programmes should be designed to feature crucial issues such as online safety and privacy and include women-centric content such as resources on reproductive health and information regarding recourse from cybercrimes. This will equip women with the knowledge and digital skills to navigate the online space and will contribute to creating a safer online environment for them. Involving women in education and training at the grassroots level also helps alleviate certain hesitations stemming from social and cultural biases.

Create a database on children’s access to and use of digital resources, with a regional focus

A major gap to overcome as a priority is data and evidence that capture digital engagement across the life course. For instance, there is barely any reliable population-based data on children’s access to and use of digital resources, disaggregated by geography, gender, and

household wealth. Addressing gender gaps between women and men is unlikely to be reversed at a fast enough scale if robust foundations for a healthy digital environment are not built during childhood and adolescence in age-appropriate formats. Moreover, gender-disaggregated data should be made available at the level of regions defined within countries rather than at the level of countries. This will allow for a better understanding of the regional differences in gender equality, their determinants, and the developments over time. In this way, it will be possible to establish a monitoring system to detect changes in the situation of gender equality and to undertake corrective actions in a timely manner, if necessary.

Leverage partnerships with the private sector and non-government organisations to design and implement digital literacy programmes

Involving the community, especially other women, in the transfer of skills helps address socio- cultural barriers and allows women to engage with society and unlock economic opportunities. Several examples, including the Canadian Digital Literacy Exchange Program and the Internet Saathi model in India, were able to actively create these partnerships to successfully address the challenges listed above.

Adopt Gender Specific Targets and Monitoring Progress

While digital literacy programmes often recognise women as beneficiaries, they fail to set gender-specific targets. Coupled with the lack of gender-disaggregated data collection, these programmes’ impact cannot be sufficiently evaluated. Given the strong persistence of regional gender-specific roles over time, it is unlikely that short-term measures, particularly if they do not account for local conditions, will successfully promote gender equality. Digital literacy programmes must be designed with gender-specific targets and mandates to track their progress, allowing policymakers to assess their implementation and develop appropriate responses.

Initiatives to promote gender equality, including educational programmes in digital literacy, should entail a location-based approach

The determinants of gender equality are at least partly defined at a rather narrow level of regions defined within countries rather than at a broad level of nations. However, the existing initiatives to promote gender equality often disregard regional variations in the determinants of gender equality. While promoting gender equality is a global objective, it can best be achieved by considering local factors that might impact gender equality.

References

Alesina, A., P. Giuliano, and N. Nunn (2013): On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 469-530.

Alliance for Affordable Internet, World Wide Web Foundation (2021): The Costs of Exclusion: Economic Consequences of the Digital Gender Gap, https://webfoundation.org/docs/2021/10/CoE-Report-English.pdf

Amanta, F., and N.F. Azzahra (2021): Promoting Digital Literacy Skill for Students through Improved School Curriculum, Policy Brief No. 11, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351342692_Promoting_Digital_Literacy_Skill_f or_Students_through_Improved_School_Curriculum

Chetty, K., J. Josie, G. Nozibele, U. Aneja, and V. Mishra (2017): Bridging the Digital Divide: Skills For The New Age, in G20 Insights, Last updated 10 December 2020, https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/bridging-digital-divide-skills-new-age/

Giuliano, P. (2018): Gender: A Historical Perspective. In Averett, S.L., L.M. Argys, and S.D. Hoffman (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.29

ITU (2020): Bringing the digital revolution to all primary schools in Kenya, https://www.itu.int/hub/2020/05/bringing-the-digital-revolution-to-all-primary- schools-in-kenya/

Lee, I., H. Jeung, and H. Kwon (2007): The Korea Agency for Digital Opportunity & Promotion’s e-Learning Initiatives to Bridge the Digital Divide in South Korea, International Journal for Educational Media and Technology in Volume 1, Issue 1 (2007) p. 35-47, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ijemt/1/1/1_35/_pdf/-char/en

Mishra, V., (2017): Gendering the G20: Empowering women in the digital age, https://www.orfonline.org/research/gendering-g20-empowering-women-in-the-digital- age/

Ogolla, K. (2018): Digital Literacy Programme in Kenya; Developing IT Skills in Children to align them to the Digital World and Changing Nature of Work-Briefing Note, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/967221540488971590- 0050022018/original/KennedyOgolaEntryDigitalLiteracyKenya.pdf

OECD (2018): Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate, https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf

OECD (2018): G20 Toolkit for Measuring the Digital Economy, https://www.oecd.org/g20/summits/buenos-aires/G20-Toolkit-for-measuring-digital- economy.pdf

OECD (2018): Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality, https://www.oecd.org/gender/governance/toolkit/toolkit-for-mainstreaming-and- implementing-gender-equality.pdf

Sorgner, A., G. Mayne, J. Mariscal, and U. Aneja (2018): Bridging the Gender Digital Gap, in G20 Insights, Last updated 10 December 2020, https://www.g20- insights.org/policy_briefs/bridging-the-gender-digital-gap/

Sorgner, A. (2019): The Impacts of New Digital Technologies on Gender Equality in Developing Countries. Background paper prepared for the Industrial Development Report 2020. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

Sorgner, A. (2021): Gender and Industrialization: Developments and Trends in the Context of Developing Countries. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 14160.

UNESCO (2018): A Global Framework of Reference on Digital Literacy Skills for Indicator 4.4.2, Information Paper No. 51, (UIS/2018/ICT/IP/51), https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip51-global- framework-reference-digital-literacy-skills-2018-en.pdf

UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition (2019): I’d blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416.page=1

UNICEF (2021): What we know about the gender digital divide for girls: A literature review https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/8311/file/What%20we%20know%20about%20the%20 gender%20digital%20divide%20for%20girls:%20A%20literature%20review.pdf

World Wide Web Foundation (2020.a): Women’s Rights Online Digital Gender Gap Audit Scorecards – Global Summary, https://webfoundation.org/docs/2016/09/WRO-Gender- Report-Card_Overview.pdf

World Wide Web Foundation (2020.b): Women’s Rights Online: closing the digital gender gap for a more equal world, https://webfoundation.org/docs/2020/10/Womens-Rights-Online- Report-1.pdf

Data

The data drawn from the target 4.4.1 are not harmonized both in terms of countries covered (to see the countries covered for each outcome variable please see the appendix) and time frame. We have thus included for each country the latest available figure which does not necessarily match with the year in which the SIGI was released (2019). However, the decision to pair these observations relies on the assumption that social norms are deeply rooted in the fabric of society and do not change overnight.

The authors have taken the suggestion made by the Secretariat in high consideration for improving the policy brief. Grouping the countries by level of digitalization rather than by level of income could make the analysis more insightful. The gender digital literacy gap (y axis in our policy brief) would be probably more influenced by the level of digitalization of a country rather than by its level of economic development. We can think that countries with low income but highly digitalized economies (e.g., India, Philippines…) would share similar features with the high developed countries (both technologically and economically) when considering the gender digital literacy gap.

However, there does not exist an index that captures the level of digitalization for all the countries in the world. The only available index is the World Digital Competitiveness Ranking that ranks 64 countries based on the capacity and readiness of economies to adopt and explore digital technologies for economic and social transformation. Nonetheless, it is interesting to notice (Figure 1) that the level of economic development of a country seems to be a good predictor of its level of digitalization. Apart from some notable exceptions (e.g., Luxemburg with the highest GDP per capita and ranked 22nd in the World Digital Competitiveness Ranking) the countries with the highest GDP per capita are also the best performer in the World Digital Competitiveness Ranking. Being digitalization and economic development highly correlated, it is thus possible that the criterion of grouping would not probably change the results of the analysis.

Figure 1: relationship between level of economic development and digitalization level

Furthermore, if the level of digitalization could provide a more in-depth interpretation of the gender digital literacy gap it probably would not be able to predict the restrictiveness of the gender social norms (x axis in our policy brief) as for the level of economic development.

For all these reasons the authors have decided to continue using the income level as criterion of grouping for the graphs in the first section of the policy brief.

References Digital Literacy Programmes

Canada, The Digital Literacy Exchange program, https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/digital-literacy- exchange-program/en

European Union, Digital Education Action Plan (2021-2027), https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/about/digital-education-action- plan

India, Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta. Abhiyaan (PMGDISHA), https://www.pmgdisha.in/

Indonesia, Makin Cakap Digital, https://aptika.kominfo.go.id/2021/05/peluncuran-literasi-digital- indonesia-makin-cakap-digital/

Indonesia, Makin Cakap Digital, https://diskominfotik.riau.go.id/2021/11/23/kominfo-ajak- masyarakat-indonesia-makin-cakap-digital-melalui-literasi-digital-netizen-fair-2021/

Indonesia, Makin Cakap Digital, https://indonesiabaik.id/index.php/infografis/makin-cakap- digital-makin-maju

Kenya, DigiSchool: The Digital Literacy Programme, https://ict.go.ke/digital-literacy- programmedlp/

Republic of Korea, Baeumnara, https://www.estudy.or.kr/estudy3.0/kor/index.asp Saudi Arabia, Attaa Digital, https://attaa.sa/library/?category_id=6

Saudi Arabia, Attaa Digital, https://www.mcit.gov.sa/en/womens-empowerment

Saudi Arabia, Attaa Digital, https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/careaboutyou/digitalinclusion

Saudi Arabia, Human Capability Development Program Delivery Plan, https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/hcdp/

Appendix

| Figure number | Variable on the y axis | Variable on the x axis | Number of countries included | Countries included |

| Figure 1 | Proportion of youth and adults who have copied or moved a file or folder (%) | SIGI (2019) | 61 | Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Brazil; Bulgaria; Cambodia; Central African Republic; Chad; Colombia; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; Georgia; Germany; Ghana; Greece; Hong Kong SAR, China; Hungary; Iran, Islamic Rep.; Iraq; Ireland; Jamaica; Kazakhstan; Kiribati; Korea, Rep.;Lao PDR; Latvia; Lesotho; Lithuania; Madagascar; Malta; Mexico; Mongolia; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; North Macedonia; Norway; Pakistan; Peru; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Russian Federation; Serbia; Sierra Leone; Singapore; Slovak Republic; Spain; Sweden; Thailand; Togo; Tonga;Turkey;United Kingdom; Zimbabwe |

| Figure 2 | Proportion of youth and adults who have sent e-mails with attached files (e.g. document, picture, video) (%). | SIGI (2019) | 36 | Azerbaijan; Belarus; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Brazil; Cambodia; Central African Republic; Chad; Colombia; Côte d’Ivoire; Georgia; Ghana; Hong Kong SAR, China; Iran, Islamic Rep.; Jamaica; Japan; Kazakhstan; Kiribati; Korea, Rep.; Lao PDR; Lesotho; Madagascar; Mexico; Mongolia; Morocco; Nepal; Pakistan; Peru; Romania; Russian Federation; Sierra Leone; Singapore; Slovak Republic; Thailand; Togo; Tonga; Zimbabwe. |

| Figure 3 | Proportion of youth and adults who have found, downloaded, installed and configured software (%). | SIGI (2019) | 59 | Austria; Albania; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Brazil; Cambodia; Central African Republic; Chad; Colombia; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; Georgia; Ghana; Greece; Hong Kong SAR, China; Iran, Islamic Rep.; Iraq; Italy; Kazakhstan; Kiribati; Korea, Rep.; Lao PDR; Latvia; Lesotho; Lithuania; Madagascar; Malta; Mexico; Mongolia; Morocco; Nepal; |

| Netherlands; North Macedonia; Norway; Pakistan; Palestine; Poland; Portugal; Romania, Serbia, Sierra Leone; Singapore; Slovak Republic; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Thailand; Togo; Tonga; United Kingdom; Zimbabwe |