Ending rural hunger by 2030 is feasible through scaled-up, data-driven efforts: We propose an evidence-based, coordinated approach to ending rural hunger, prioritizing countries with high needs, good policies and low levels of resources per capita.

Challenge

Ending hunger is the second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). Reflecting hunger’s multi-dimensional nature, the goal has four country-specific targets to be achieved by 2030: (i) end undernourishment, (ii) end malnutrition, (iii) double agricultural productivity of small-scale producers, and (iv) ensure sustainable and resilient agricultural practices. For each target, with the exception of sustainability, there have been improvements over the past decade, but at a speed that still leaves too many countries and the global aggregate missing the mark by a wide margin by 2030. For example, nearly 800 million people in the world are estimated to be undernourished today. A business-as usual scenario would see this number only fall to around 500 million people by 2030, and still leave at least 54 countries1 -track for eliminating hunger by that year – substantial progress, but nowhere near the SDG objective of essentially zero. Roughly three-quarters of today’s undernourished people live in developing countries’ rural areas, so the challenge, therefore, is to implement programs at scale that will transform the rural space. This requires changes in how the international community prioritizes and allocates its financial resources.

Proposal

Ending hunger in rural areas requires an evidence-based framework for targeting transformational change in many regions’ local food and agricultural systems. This is about more than growing enough food — it is about demand for as well as supply; quality as well as quantity; an adequate diet today and assurance of one tomorrow. The Food and Agriculture Organization calculates that about half the world’s hungry people are smallholder farmer families and 20 percent are landless families dependent on farming. Therefore, food security requires a particular focus on the needs of small-scale farms, including the special challenges faced by women farmers. Today there are about 500 million small farms, and they provide livelihoods for up to 2.5 billion rural people. Much of the march to end hunger will be determined by what happens on these farms. For at least 40 years, global political commitment to food and nutrition security has fallen short of the task, as have the associated reforms of policies and public investments. Attention has tended to wax and wane alongside trends in food prices. When prices spike upward, politicians come forward with new promises and commitments. But when prices subside, urgency is lost and attention dissipates. There has been too little long-term strategy or accountability. Our recommendation is to organize and target support around national, evidence-based programs for ensuring universal food and nutrition security by 2030. These programs can follow a straightforward three-part logic focused on needs, policies and resources (see Figure 1).

The first part is to examine available data to identify the nature of local needs and priorities. For example, in some places the focus should be on agricultural productivity, while in others it should be on nutrition or access to food. The second part is to identify policy constraints that impede advancement in these areas. Our research suggests that better policies are an important determinant of food and nutrition security, even after accounting for region and income levels. The third part is to identify key investments that might be needed, either directly into agricultural support systems – for example in the construction of agricultural science and extension services; or indirectly toward the inputs that support agricultural markets, like rural roads, rural electrification, seeds, soil nutrients, and access to rural finance; or via support to households through rural safety nets. Again, research suggests that public investments do have an impact on food and nutrition security.

The international community can support these national efforts in four ways.

First, all countries can help make sure global food markets are more integrated and less distorted. There is some good news in this regard. Subsidies given by developed countries to their own farmers, and the associated trade restrictions that protect them from imports, have for the most part fallen substantially. While still high in too many cases, these subsidies and border tariffs and non-tariff barriers are at their lowest level in a generation. The recent agreement in Nairobi on the elimination of agricultural export subsidies marks another step in the right direction2.

For their part, developing countries have also reversed previously long-held anti-agricultural biases in their development strategies. More balanced and inclusive growth is likely to benefit both farm and off-farm rural development. In some instances, specific parts of the market need strengthening. For example, Africa has few commodity exchanges to help with real-time price discovery. The markets for improved seeds and for fertilizers also need strengthening.

One exciting recent development toward correcting underlying market failures is the growing feasibility of commercially viable insurance products for farmers. Farming is inherently risky, leading many to adopt lowest-risk rather than highest-return farming strategies. More efficient risk-sharing could be transformational. Government-level risk instruments like the African Risk Capacity mechanism can also help to mitigate the effects of wide-spread disasters3.

As a general rule, small-scale farmers and women farmers deserve special focus throughout all efforts aiming at market enhancement. Small-holders would benefit from greater political voice, better ability to access government programs targeted to large agribusiness interests, and inclusion in commercial supply chains. Women farmers may need targeted delivery to access extension and rural financial services, as well as legal reform to grant them property rights.

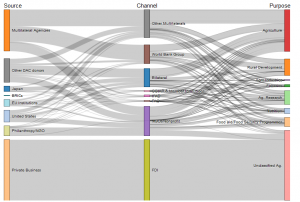

Second, the international community could invest more and better resources for global food and nutrition security, and do so with greater efficacy per dollar. We have recently made a first attempt to map the pathways of relevant international financing flowing to developing countries (Figure 2).

(Total flows equal $28.6 billion in constant $2013)

While grant-based investments for food and nutrition security (FNS) increased substantially after the food price spikes of 2007/2008, they have stagnated for the last six years in real terms. Significant foreign resources for rural development are also being made available in the form of non-concessional lending by development finance institutions, south-south cooperation and commercial foreign direct investments but these resources, too, are not rising in real terms, leaving significant unfilled financing gaps.

There is considerable scope to make FNS aid more effective. The highest value-for-money will come from targeting countries where the needs are large, where there is a supportive policy environment and a committed government, but where investable resources into the rural area are in short supply. High impact projects and programs can also be prioritized within countries. For examples, our research has highlighted the limited amount of aid going towards nutrition, despite considerable evidence documenting the high social returns to improved nutrition. Aid volatility is also a major problem to be addressed, since it has the potential to lead to a 20% reduction in effectiveness. FNS resources need to be committed as long-term and predictable sources of investment.

Third, the international community can do more to invest in agricultural research, extension, and evidence, especially in developing countries themselves. This includes research for neglected tropical crops, for helping to make existing crops more resilient to climate change (droughts and floods), and for adapting recommendations to suit local conditions and improve uptake. There remains considerable scope for improving yields, especially of staple crops, which forms one of the surest pathways to ending hunger for the most vulnerable households. There are also too many areas where the underlying evidence remains weak. For example, there is no data for small-holder agricultural yields, despite the SDG2 target to double small-holder yields by 2030. Similarly, there is no reliable evidence on the size of food loss and waste. Building the relevant data systems will be crucial to inform evidence-based policies, resource allocations, and accountability.

Fourth, the international community can institute outcome-oriented cooperation across relevant organizations and initiatives. Many platforms and partnerships have emerged recently to tackle these issues of markets, resources and science. A number of high-level multilateral initiatives have also been announced at major meetings of the UN, G-20, G-7, and African Union. If properly scaled and sustained, these could signify the start of long-term international leadership guiding the end of hunger. But they need to focus clearly on outcomes. Fortunately, there are a number of prominent national examples to draw from, such as in Brazil and Ethiopia, illustrating how political leadership can play a crucial role in fighting hunger.

Bringing these strands together will require a systematic commitment to review and follow-up, based on the best available evidence. The “Ending Rural Hunger” project and online database offers one tool for assembling information on country needs, policies and resources in food and nutrition security. It provides a one-stop platform for comparative evidence. We recommend that leaders across the world make use of this or other tools to construct their FNS strategies in an informed and sustained manner. Doing so can help ensure SDG 2 is achieved within 15 years.

References

- John McArthur / Krista Rasmussen:

How close to zero? Assessing the world’s extreme poverty-related trajectories for 2030 - Heinz Strubenhoff:

The WTO’s decision to end agricultural export subsidies is good news for farmers and consumers - African Risk Capacity

More Information