This Policy Brief proposes recommendations to promote greater understanding and consensus around policies that will foster data free flows with trust (DFFT) across borders. It takes up the mandate agreed under the G20 Japanese Presidency in 2019 as set out in the G20 Osaka Leaders Declaration. The Policy Brief recognizes the multi-dimensional nature of the issues and actors involved when discussing DFFT. Suggested actions are aimed at generating greater trust around data flows on the part of individuals and governments. These actions address wide-ranging issues, including trade, regulatory cooperation, personal data privacy protection, and initiatives to increase private sector responsibility and coordinated government action. These should be viewed as complementary and mutually reinforcing recommendations towards meeting the DFFT objective.

Challenge

THE CHALLENGES AROUND DATA GOVERNANCE AT PRESENT ARE NUMEROUS:

· First, there are no agreed multilateral rules governing regulatory aspects to cross-border data flows, and governments have taken very different approaches towards them. The global economy is experiencing a rapid fragmentation of jurisdictions over data governance with numerous regimes that have carved up the world economy into “digital silos”.

· Second, the number of restrictions applied to digital trade is multiplying. The OECD has noted that of the numerous digital trade-related measures enacted over the past decade, more than one-third affect the use, storage and transfer of data. Evenett and Fritz (2021) estimate that a total of 287 new policy measures relating to use, transfer and storage of data were introduced by governments between 2010 and 2020. Many of these measures are restrictions on data flows that create large costs to firms and the world economy (Ferracana and Van der Marel 2018).

· Third, it is not well understood how data is “different” from other aspects of traded goods and service, although we know that data is non-rivalrous, non-depreciable and is currently without standard valuation and typology frameworks. (Aaronson 2018) There are also challenges concerning how the DFFT vision can be implemented beyond a bilateral context, across multiple institutions, regions and stakeholders. The vision has been developed on the issue linkages between openness and trust, but these depend on each relationship, which raises the question as to what the least common denominator of trust will be on a G20 basis.

· Fourth, trade disciplines are not the primary means of building trust. Trade agreements only guarantee an openness that is appropriate to the pre-existing level of trust. Many of the issues impacting upon data flows (privacy, product regulations and standardization on AI, big data, cybersecurity, financial regulations and oversight) lie outside the trade arena but are also critically important to the conduct of trade (IMF, 2021). Existing trade agreements cover only some barriers (performance requirements, data localization) and not others, such as internet shutdowns for political reasons. But these actions clearly undermine market access (Aaronson 2021 forthcoming).

· Fifth, there is a growing imbalance between economies in the world regarding digital technologies. Thanks to a wide dissemination of mobile internet, the “digital divide” between industrialised and developing countries has been transformed into a divide between the producers of online services and the users (Fisher and Streinz 2021).

WHO IS LACKING TRUST IN THE FREE FLOW OF DATA?

Currently, many individuals distrust corporations and governments as they worry personal data may be collected and exploited without their explicit consent. Many oppose international transfer of their personal information to jurisdictions where data protection is weaker, not properly enforced, or where they may lack judicial rights to redress. A December 2020 poll by the Oxford Internet Institute found that 71% of internet users are worried about how their personal data may be collected, analyzed and monetized (Aaronson 2021).

In response, governments attempt to either ‘territorialise’ data by demanding that personal information (or other sensitive data) stays within their jurisdiction by applying their privacy, fiscal and security laws in an extra-territorial manner or by banning cross-border flows of certain personal (or other types of) data. This generates a lack of trust and creates conflicts between governments. Without putting in some systems and processes that can help to establish trust, the number of restrictions around data flows will continue to grow.

However, causes to distrust are multiple. There is no singular path to building trust for all relationships, and therefore this process is much more complex than setting out minimum regulatory standards or agreeing to commitments for trade openness in trade agreements. While rules on data flows are important for ensuring transparency, predictability and stability of the multilateral system, trust around data flows can primarily be achieved indirectly through making progress in two areas.

1. First, at the national level, addressing the issues that are of concern to people online through allowing users to have more agency over how their personal data is collected and used. A user-centric approach, similar to that advocated by Snower and Twomey in a companion Policy Brief in the T20 Task Force 4 and the Government of Japan’s approach to “Society 5.0”, are key to creating trust domestically.

2. Second, at the international level, promoting increased regulatory cooperation between governments in order to reach understandings on interoperable privacy regimes as well as on permissibility or liability for the development and application of new technologies such as AI and behavioral analytics, among other.1 Trust becomes a horizontal issue in a cross-border context.

Below are five recommendations focused on building trust around the collection, use and cross border flows of personal data that should serve to enhance trust on the part of individuals about the use of their data as well as between governments with different data governance systems.

Proposal

Regional certification schemes governing cross-border flows of personal data in APEC and the EU should be opened up to outside countries and multilateralised, with the prospect of moving towards interoperability in the future.

Development of a common and universal privacy charter should be initiated by the G20 so as to facilitate development of future interoperable mechanisms.

There exists a broad range of legislation, principles and guidelines at the national, regional and multilateral levels that has been developed over the past more than two decades to deal with personal data protection and international data flows. National and regional divergence in approaches mean that firms are faced with differing compliance requirements in different jurisdictions, a situation that restricts trade and increases both costs and uncertainty around data flows.

Exclusive regional transfer mechanisms governing cross-border flows of personal data have been developed by APEC economies in the form of the APEC Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) and by the EU under the framework of its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). APEC’s CBPR is a certification-based method based on accountability where businesses (rather than governments) are trusted to transfer personal data based on their proof of ability to comply with privacy requirements. The EU GDPR approach is one based on overarching principles, under which personal data may be transferred out of the EU to another jurisdiction only if and when that jurisdiction is deemed to be “adequate” in meeting specified conditions for the treatment of this data. Together, the economies from these two regional groupings represent three-fourths of world trade (28% of world trade in goods and services for the EU and 47% for APEC in 2020) and encompass nearly all of the major traders in the global economy.

Given the economic importance of these two groupings, it would be beneficial to open up these systems for wider participation as a step towards encouraging long-term harmonization of the underlying privacy rules. Both regional schemes should allow any country who wishes to apply to be a part of its respective system if they objectively meet the criteria. There is no practical or legal reason why a non-APEC nation could not be a part of the CBPR system. While full interoperability between these two regional mechanisms is considered infeasible by many at the moment, these approaches are not necessarily conflicting, and some countries (such as Japan and Korea) have been able to meet the requirements of both systems.

Elaboration of a “common and universal privacy charter” based on common principles and elements would be useful to facilitate future interoperability between these two and other regions. Progress towards an understanding on interoperability that can help serve as the basis for operationalizing the “data free flow with trust” is needed as quickly as possible.

Action: The G20 should request members of APEC and the EU to open up or “multilateralise” their regional certification schemes governing cross-border flows of personal data to outside countries.

Members of the G20 should decide if they wish to engage in conversation about a Universal Privacy Charter.

Negotiations within the WTO JSI E-commerce initiative should be concluded expeditiously, but should also include endeavour or “soft law” provisions on regulatory issues that will promote trust between governments around data flows.

Binding trade rules by themselves to ensure the cross-border flow of data will not by themselves directly create trust. However, they can be an important contribution to creating trust, by subjecting signatory governments to disciplines which forbids them from imposing regulations that are arbitrarily discriminating

The WTO is the central institution in establishing an updated set of global trade rules to underpin the digital economy. Services regulations rarely make a distinction between foreign and domestic entities but instead discriminate on the basis of their non-national origin (non-national treatment). This is particularly true for online services that, unlike traditional services, are spawned with a global reach. As the internet is multilateral by default, diverging regional and national rules could lead to balkanization rather than globalization. An agreement among the 86 WTO members currently participating in the JSI E-commerce negotiations would constitute the largest number of countries signing onto a trade agreement covering the digital economy and would be an important step towards reducing the risk of such balkanization.

There are many issues for which binding disciplines are being sought, including the guarantee of cross-border data flows, the recognition of digital or e-signatures, authentication, prevention of spam (unsolicited personal communications), the validity of electronic contracts, online consumer protection and the prohibition of data localization requirements, among others. Binding rules aim to limit restrictions or discrimination to occasions and objectives that are legitimate and genuine in order to make digital trade and data flows more stable and predictable (Drake-Brockman et al. 2020).

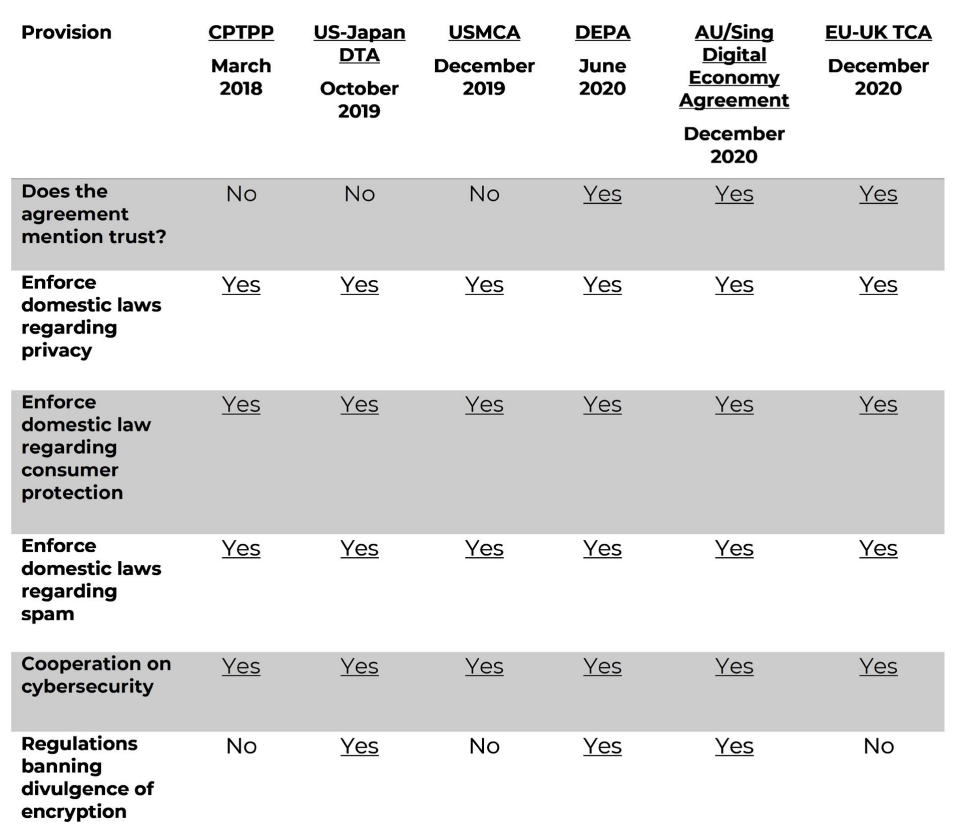

However, the creation of trust between governments would also importantly need to be addressed through parallel discussions on regulatory cooperation between national regulators. The WTO JSI E-commerce agreement could build upon progress in digital trade agreements, namely the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA), the AustraliaSingapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA), as well as the CPTPP, the USMCA, the US-Japan DTA and in recent EU FTAs, all of whose members agree to carry out regulatory cooperation on digital trade issues. Three recent trade agreements explicitly mention the objective of creating trust around data flows and digital trade. The table in the Annex canvasses provisions in the latest trade agreements that address privacy and consumer protection.

Action: The G20 should advocate that WTO members who are negotiating the JSI E-commerce agreement incorporate elements promoting parallel, non-binding regulatory consultations and cooperation to ensure that national regulators interact with each other on the operation of their privacy laws as well as on a wide range of other issues involved in digital trade that may not be codified in binding rules.

Schemes for giving users greater agency over their data and for sharing the value of data such as the creation of a “privacy marketplace” or “data trusts” should be advanced in order to generate trust with regards to the way firms treat data from individuals they collect and process.

Schemes can be envisaged that would allow for different ways in which personal data is used than is currently happening, to ensure a more equitable sharing of the value of data between firms and individuals, while respecting the conditions of privacy. One way of doing this would be through the creation of a “privacy marketplace” where firms could trade consumer data but individuals would retain centralized control and specify in advance how their information can be treated. Firms could be required to compensate users who allow their data to be used in surveys and other activities.

“Data trusts” are an alternative to a privacy marketplace where users can manage their data but without the necessity of giving consent to every firm involved in every transaction, allowing for a trusted third party to streamline the complex web of data management responsibilities. This gives individuals the assurance that their data will be collected, processed and used in a way that was agreed upon prior to entry into the arrangement. Commercial firms would only be able to access a data trust according to the agreed rules and with the oversight of an appointed and neutral third-party authority.

The EU has made an early attempt to regulate (and to localize) these novel ways of data-sharing through its Digital Governance Act of 2020. It is also encouraging a national private-public “data trust”. Many similar attempts to both create and regulate national data trusts should follow in due course.

Questions of who would create and run these data utilities and on what basis for profit or for the public good are challenging and will need to be defined. An issue of concern is the need for government regulation of data trust schemes so as to ensure that firms do not hoard data, reducing its economic usefulness. The cross-border dimensions of these entities also warrant a discussion on their legal standing in the light of existing commitments under trade law, as some of the attempts to promote local data trusts may not be consistent with existing trade commitments.

Action: The G20 should encourage relevant institutions to develop the details for data utilities/trusts that would give individuals legal assurance and trust over how their personal data is used.

The “notice and consent” model should be re-designed to create better defined ways to ensure that people have meaningful “agency” over their data so as to generate trust in how they are used.

There is a broad consensus that the “Notice and Consent” procedure relied upon by many countries to guarantee individuals the right to make choices with respect to the use of their personal data is not working well. The requirement for individuals to make informed choices through ticking small boxes on a one-off basis relies upon their time and ability to both read and understand the complex legal text involved, neither of which is usually present. It also relies on the individual believing that his /her data is actually going to be “private” after clicking the box, which is in fact not the case.

More generally, the “Notice and Consent” system was designed primarily for a world of e-commerce and is not adequate for real privacy protection in a world where data on individuals are collected through a myriad of online behaviors and sensory devices, on websites, within mobile apps and “smart” products. Cisco estimates that globally there will be over 27 billion Internet-connected or networked devices in 2021, up from 17 billion in 2016. The “Notice and Consent” procedure is static and unable to handle the complexity of these numerous data-sharing relationships that individuals enter into on a daily basis. What is needed is a broader concept of agency, or individual privacy, combined with a system that works well in the modern context where so much of our daily lives are defined by online behavior. Alternatives to the existing “Notice and Consent” should be technology-neutral and ethically grounded (WEF 2020C).

Action: The G20 should encourage the development of alternatives to the existing “Notice and Consent” on the basis of multi-stakeholder participation, including experts in technology and human behavior.

“Guidelines for Business Conduct toward Data Flows” should be developed in order for trust to be created with respect to the behavior of multinational enterprises.

The private sector at present has only a few guidelines to follow for its conduct with respect to data flows, the collection and use of private information and the activities it carries out on digital platforms. A useful step in generating trust toward the behavior of private firms would be the development of “Guidelines for Business Conduct towards Data Flows” similar to the “OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises” that were first agreed in 1976 and updated in 2011. These Guidelines set out principles for responsible business conduct in a global context consistent with applicable laws and internationally recognised standards, as well as implementation procedures for putting them into practice.

This proposed companion set of business guidelines for data flows would define the parameters for actions the private sector should follow with regard to the treatment of personal data, transparency obligations and accountability practices. The Guidelines would be open for any country wishing to join them. Such an effort would create greater trust through instilling corporate social responsibility around data flows.

Thought would need to be given to who would monitor the application of these Guidelines on the part of firms. Options could include a G20 body (through the proposed Data Governance Board in the recommendation below) or the OECD.

Action: The G20 should take on the responsibility of developing “Guidelines for Business Conduct towards Data Flows” to complement the OECD Guidelines for the Conduct of Multinational Enterprises. Work on this should be initiated under the new proposed Data Governance Board.

A “Data Governance Board” should be created within the G20 framework to bring coherence to the discussion of data flows and the development and application of new digital technologies.

The consideration of issues relevant to data flows and data governance is currently spread across a variety of organizations. Greater coherence should be brought to efforts to address data flows together with the wide range of digital and new technology issues so as to give more focus and visibility to dispersed work streams.

It is time to coordinate the discussion of data flows and data governance within a “Data Governance Board” created under the G20 framework.2 Such a Board would gather regulatory agencies from the G20 countries to develop greater understanding on data-relevant issues ranging from the alignment of AI frameworks to cyber security and the interoperability of privacy frameworks for data flows. It would ensure that ethical questions around new technologies are incorporated into these discussions and resulting recommendations.

Discussions in the proposed Data Governance Board would call upon the expertise of organizations that are carrying out substantive work on data flows and digital issues, including the WTO, APEC, the OECD, the World Economic Forum, the IEEE and others, to bring current knowledge and relevant work into one place for discussion, drawing upon multi-stakeholder participation as appropriate.

Action: The G20 should create a “Data Governance Board” to begin functioning in 2022 and require this new body to provide a report annually on progress achieved in implementing the G20 “Data Free Flows with Trust” mandate.

APPENDIX

PROVISIONS IN RECENT TRADE AGREEMENTS ADDRESSING PRIVACY FOR PERSONAL DATA AND CONSUMER PROTECTION

Table by A. Kraskewicz with S. Aaronson. Source: From Trade to Trust: A Different Approach to the Free Flow of Data across Borders, forthcoming CIGI, August 2021.

NOTES

1 A major step towards increased regulatory cooperation was taken at the G7 meeting of Digital and Technology Ministers (April 2021) when they agreed to create a Roadmap for Cooperation on Data Free Flow with Trust. The Roadmap sets out a plan for joint action between the G7 countries in four cross-cutting areas relevant to data flows, namely: data localization; regulatory cooperation; government access to data; and data sharing. https://www.g8.utoronto.ca/ict/2021-annex_2-roadmap.html

2 This proposed new Data and Technology Governance Board would have a broader and more representative participation of governments under the G20 framework than the new Trade and Technology Council created at the G7 Summit on 15 June 2021 by EU and US leaders, although some of its scope would be similar. The latter is to serve as a forum for the coordination of approaches to key global trade, economic, and technology issues (Press Release, European Commission, 2021). Five of the 10 Working Groups to be established will address issues related to digital technologies, including on technology standards cooperation and on data governance and technology platforms.

REFERENCES

Aaronson S.A., Data is Different: Why the World Needs a New Approach to Governing Cross-border Data Flows, CIGI Papers No 197, November 2018 https://www2.gwu.edu/~iiep/assets/docs/papers/2018WP/AaronsonIIEP2018-10.pdf

Aaronson S.A., From Trade to Trust: A Different Approach to the Free Flow of Data across Borders, forthcoming CIGI Papers, forthcoming August 2021

Aaronson S.A., How Nations Can Build Online Trust through Trade, Barrons commentary, May 2021 https://www.barrons.com/articles/how-nations-can-build-online-trust-through-trade-51620139281

APEC Privacy Framework, 2015 https://cbprs.blob.core.windows.net/files/2015%20APEC%20Privacy%20Framework.pdf

APEC Cross Border Privacy Rules System https://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/Fact-Sheets/What-is-the-CrossBorder-Privacy-Rules-System

Carrière-Swallow Y. and V. Haksar, Let’s Build a Better Data Economy, IMF Finance and Development: How to Build a Better Data Economy, March 2021 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2021/03/pdf/how-to-build-a-better-data-economy-carriere.pdf

Drake-Brockman J. et al., Impact of Digital Technologies and the Fourth Industrial Revolution on Trade in Services, THINK 20 Policy Brief, 2020 https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/impact-of-digital-technologies-and-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-on-trade-in-services/

European Commission Press Release, EUUS launch Trade and Technology Council to lead values-based global digital transformation, June 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_2990

European Union Commission, Principles of the GDPR https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/rules-business-and-organisations/principles-gdpr_en

Evenett S. and J. Fritz, “Mapping Policies affecting Digital Trade”, in I. Borchert and L.A. Winters, Addressing Impediments to Digital Trade, Vox EU CEPR online volume, April 2021 https://voxeu.org/content/addressing-impediments-digital-trade

Ferracana M.F. and E. van der Marel, The Cost of Data Protectionism, ECIPE, 2018 https://ecipe.org/blog/the-cost-of-data-protectionism/

Fisher A. and T. Streintz, Confronting Data Inequality, Institute for International Law and Justice Working Paper, April 2021 https://www.iilj.org/publications/confronting-data-inequality/fisher-streinz-confronting-data-inequality-iilj-working-paper-2021_1/

Government of Canada, Digital Public, Digital Content Governance and Data Trusts – Diversity of Content in the Digital Age, 2020 https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/diversity-content-digital-age/digital-content-governance-data-trust.html

Kimura F. et al., The Digital Economy for Economic Development: Free Flow of Data and Supporting Policies, THINK 20 Policy Brief, 2019 https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-digital-economy-economic-development/

World Economic Forum A, It’s Time to Redefine how Data is Governed, Controlled and Shared: Here’s How, January 2020 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/future-of-data-protect-and-regulation/

World Economic Forum B, Beyond Trust: Why We need a Paradigm Shift in Data Sharing, January 2020 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/new-paradigm-data-sharing

World Economic Forum C, Redesigning Data Privacy: Re-imagining Notice and Consent for human-technology interaction, July 2020 https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Redesigning_Data_Privacy_Report_2020.pdf

World Economic Forum D, A Roadmap for Cross-Border Data Flows: Future-Proofing Readiness and Cooperation in the New Data Economy, White Paper, June 2020 https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_A_Roadmap_for_Cross_Border_Data_Flows_2020.pdf