For over two decades, the gender and corruption nexus has been largely addressed based on the gender-biased premise that women would be less tolerant towards and less prone to corruption. As a consequence, significant resources were poured into feminising decision-making, the judiciary and law enforcement, as a quick fix to corrupt practices, and into investigating the social and ethical grounds for such an articulation. This policy brief, by contrast, aims to reframe the whole issue and recast global anti-discrimination efforts according to an evidence-based, transformative approach. Acknowledging the complexity of gender as a concept and bringing an intersectional focus, it tackles gendered forms and impacts of corruption through five actionable policy recommendations.

Challenge

Over the past two decades, a myth has been created around the assumption that women are intrinsically more risk-averse, honest and thus less prone to engage in corrupt practices than men, thereby emphasising alleged psychological and moral differences between men and women (Dollar, Fisman and Gatti 2001). However, the emerging gender and corruption scholarship has shown that honesty and integrity are not inherent to one specific gender (Sung 2003), that the unequal distribution of power and resources restricts women’s opportunities to engage in corruption (Goetz 2007) and that higher levels of corruption occur in countries where social institutions deprive women of their right to actively participate in public life (Chêne & Fagan 2013). Although finer-grained and empirically grounded, this literature has so far largely focused on debunking the original myth, which is especially popular and thus resilient among governments engaged in gendering their anti-corruption agendas. Twenty years later, a new approach to gender and corruption is required, that moves away from the original nexus between gender and corruption, towards acknowledging its multi-layered complexity and potential contribution to fighting corruption more effectively.

Corruption affects the essential principles of democracy and the rule of law (United Nations 2004). It thus undermines the realisation of human rights, especially with regard to the most vulnerable groups, such as women belonging to socially disadvantaged segments of society, as well as ethnic, linguistic, or religious minorities, and LGBTQ+ people. Corruption is thereby further exacerbating intersecting inequalities, especially in lowand middle-income countries (LMIC), where the magnitude of corrupt practices and their consequences is higher (Transparency International 2017). Although corruption is also affecting developed countries, the vast majority of countries ranked beyond 50th position in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (2020) are LMIC, which is also the case for the Global Gender Gap Index published annually by the World Economic Forum. However, existing anti-corruption policies have been largely gender-blind, e.g. insensitive to specific gendered impacts of corruption (Hossain, Nyamu Musembi and Hughes 2015). The main reason is the dominant focus on grand corruption in formulating solutions to the problem. This narrow understanding disregards other types of corruption that directly impact vulnerable groups, thereby contributing to making global anti-corruption efforts less effective (Hossain et al. 2015), since women are still among the first victims of both grand and petty corruption (Fuentes Téllez 2018).

We argue that governments, international organisations and civil society organisations (CSOs) should now engage in reframing the nexus between gender and corruption and recasting their anti-corruption agendas from a gender perspective. This goes with critically reviewing the different aspects of gender and corruption, and with a clear emphasis on the gendered impact of corrupt practices. Formulating evidence-based anti-corruption strategies further requires expanding our understanding of what corruption entails, and acknowledging the complexity of gender as a concept and its intersection with other inequality grounds. These first two steps will enable us to propose actionable policy recommendations with different levels of institutionalisation and involving a variety of stakeholders.

Proposal

REFRAMING GENDER AND CORRUPTION

WOMEN AND VULNERABILITY

Women are exposed to particular vulnerabilities. This does not result from their sex but from a range of social and structural factors. Gendered vulnerabilities originate in complex social hierarchical structures based on normative gender roles. The notion and scope of gendered vulnerability have been expanding over time, in the realm of global challenges such as climate change, the financial crisis and currently the COVID-19 pandemic, all of which proved to have specific impacts on women, especially in LMIC (World Bank 2020). Over-represented among the poorest (Sánchez-Páramo and Munoz-Boudet 2018) due to their unequal access to education and resources, and their lower enrolment in formal and paid employment, women are disproportionately affected by economic crises and subsequent cuts in public spending or policy reforms. The COVID-19 pandemic further evidenced the gendered structure of both paid and domestic work, highlighting women’s contributions to the functioning of our societies as much as their greater exposure to its social and economic consequences (Azcona et al. 2020), notably due to the double burden of work and family responsibilities.

GENDER-BASED CAUSES OF CORRUPTION

While there is a growing consensus on the correlation between increasing levels of women’s involvement in public life and lower levels of corruption, more nuanced research has questioned whether this is a causal relationship. Sung´s (2003) “fairer system” theory argues that the countries where women are more represented in governments, also tend to have more liberal democratic institutions, providing for more effective checks on corruption. A structural understanding of this relationship also demonstrates that, due to their limited access to power, resources and networks, as well as their lower level of agency, women tend to be less involved in corruption. Their actions are shaped by the structural contexts in which they operate. Hence, policymakers have asked the wrong question when analysing what women can do for good governance, instead of tackling the actual challenge of what governments should be doing for women (Goetz 2007). Therefore, a shift from instrumentalising women in the fight against corruption through the feminisation of public agencies, towards a structural and gender-sensitive approach, is necessary.

GENDER-BASED ATTITUDES TOWARDS CORRUPTION

Research has long suggested that there is a difference between women’s and men’s level of tolerance for corruption (Swami, Azfar and Knack 2000). However, it is not conclusive whether this difference can be applied universally, as tied to gender, or if it is a consequence of the cultural, social and political context (Alatas, Cameron, Chaudhuri, Erkal and Gangadharan 2009). A possible explanation is the different social roles of men and women across various cultures and institutional contexts, which play an important role in their individual exposure and level of agency. Tolerance and acceptance of corruption are thus indexed to being exposed to it more frequently in daily life, thereby reflecting societal norms in individual behaviours (Alatas et al. 2019). Hence, gendered power relations, rather than ethical values, seem to be at stake.

GENDER-BASED IMPACT OF CORRUPTION

While scholars have focused closely on the likelihood of men and women engaging in corrupt practices, little attention has been paid to their differential impact on gender, which is threefold. First, the gendered dimension of poverty and the intersection of gender with other inequality grounds increase women’s dependency on public services and subsidies, while decreasing their capacity to access those services or commons (especially basic health and education services), if this entails paying bribes. Consequently, corruption not only works as a tax on the poor, thus undermining efforts to break the cycle of poverty, but also generates additional obstacles for women in accessing public goods and full citizenship (Chêne and Fagan 2013). Second, the greater impact of corruption on women in sectors such as health and education also results from their social role as primary caregivers, by which they are placed more frequently in scenarios for petty corruption (Ferreira et al. 2014; UNDP 2012). Third, women, including the most marginalised, due to intersecting inequalities, are not only regarded as more susceptible to coercion, violence and threats (Hossain and Musembi 2010), but are also especially targeted by specific forms of corruption, such as sextortion or human trafficking. These are largely under-reported as they are not always perceived as corruption, and victims may fear enduring social stigmatisation (Chêne and Fagan 2013). Gendered forms of corruption also extend to LGBTQ+ people, who are disproportionately at risk of being sexually abused (NSVRC 2012).

EXPANDING THE UNDERSTANDING OF CORRUPTION PRACTICES

Corruption is a multi-dimensional concept, as it can occur in various forms and make useof diverse types of currency. Until now, the scope of anti-corruption practices has been largely limited to tackling the notion of grand corruption, which is understood as “corruption that pervades the highest levels of government, engendering major abuses of power” (United Nations 2004). Grand corruption mainly occurs at the state level, when high-level politicians seek and obtain private gains at the expense of society at large, thereby undermining equality and development (Transparency International 2016).

While grand corruption undoubtedly has a gendered impact, through diverting public resources from basic infrastructure and investment in health and education, this focus in fighting against corruption overlooks the major and widespread impact of petty corruption, especially on vulnerable groups. Petty corruption is a form of corruption that occurs in day-to-day life, involving the “exchange of very small amounts of money, and the granting of favours” (United Nation 2004), both in the public and private spheres. It is a key part of corruption, which directly and predominantly impacts women in LMIC, often translating into paying bribes for access to basic health and education services or into sextortion (UN Women and Transparency International 2019).

The focus of existing anti-corruption policies is thus flawed and gender-blind, and still largely overlooks the fact that, through both grand and petty corruption, access to basic commons is hampered every day for the most vulnerable groups, especially those defined by the intersection of gender with one or more inequality grounds. By reshaping the way corruption is understood, this brief suggests reframing the anti-corruption agenda to tackle uncovered portions of corruption and support them with actionable recommendations for effective gender-sensitive policies.

ACKNOWLEDGING THE COMPLEXITY OF GENDER AND INTERSECTIONALITY

Policy documents and scholarly works on the topic reveal that the terminology “gender and corruption” usually refers primarily to “women and corruption”. As a result, the conceptual distinction between gender as a complex social concept and sex as a biological category is often lost. This leads research and policy recommendations to reproduce gender binarity and stereotypes, by asking if women are the “fairer” sex, while leaving the underlying structure of gendered power relations that shapes corrupt practices unaddressed. Additionally, the category “women” is framed homogeneously, failing to account for multiple forms of discriminations grounded in intersecting inequalities based on e.g. ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, income, age, disability, marital status or nationality. These do not merely add to one another but tend instead to multiply, thus creating situations of greater exposure and vulnerability to corruption.

This narrow framing also fails to acknowledge the full complexity of gender as a concept, which encompasses dimensions such as sexual orientation and gender identity. This is detrimental to a proper articulation of the gender and corruption nexus, as LGBTQ+ individuals suffer specific vulnerabilities. This is especially the case in societies where they benefit from lower levels of legal protection, which increases their risk of exposure to threats, violence and (s)extortion by corrupt officials (UNODC 2020). These are the reasons why we have designed policy recommendations that are responsive and sensitive to the complexity of gender, and explicitly refer to the notion of intersectionality.

RECOMMENDATIONS: LEVERS FOR CHANGE

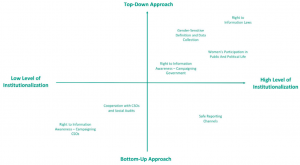

The recommendations formulated in this brief aim to outline an approach that is both bottom-up and top-down, to achieve gender-sensitive anti-corruption agendas through varying levels of institutionalisation. The recommendations are summarised in the figure below.

Fig. 1 Summary of Recommendations

GENDER-SENSITIVE DEFINITION OF CORRUPTION AND DATA COLLECTION

Redefining the Gender and Corruption Nexus Since corruption is usually defined in a narrow, male-centric way excluding gender-specific types of corruption, anti-corruption measures should be redefined to comprehensively understand and tackle its gendered impact:

- Different forms of corruption that have a strong gender dimension (such as sextortion, human trafficking and petty corruption) must be recognised and defined as such by institutions and practitioners. They should constitute a specific focus of any anti-corruption endeavour. This means that state institutions need to ensure that justice systems have the appropriate tools to register, investigate and prosecute these cases, and undergo adequate training to deal with cases of sextortion. Moreover, anti-corruption strategies should specifically target petty corruption linked to the delivery of basic common goods, such as health and education, which disproportionately affects women due to their role as primary caregivers.

- To address the full scope of corruption, gender-sensitive measures should entail a differentiated understanding of gender, thereby referring to structurally unequal power relations between men and women and to relevant aspects such as sexual orientation or gender identity. This will shift the scope towards a less binary and naturalised understanding of gender as a concept.

- Moreover, gender-sensitive anti-corruption measures should address women in their diversity, paying specific attention to mutually reinforcing intersecting inequalities leading to different levels of exposure to corruption.

Ensuring Comprehensive Data Collection

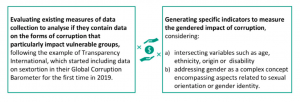

To accurately assess the situation and formulate adequate policy responses to the gender dimension of corruption, differentiated, gender-disaggregated data collection and analysis is necessary, specifically on gendered types of corruption. This would make it possible to identify gender-specific gaps in the current governmental and non-governmental efforts to promote good governance. Thus, new indicators are required to better capture the gender dimension of corruption, as well as more systematic collection and analysis of data on the relationship between gender and corruption.

This should entail:

AWARENESS-RAISING AND RIGHT TO INFORMATION

Women belonging to especially disadvantaged groups (as well as disenfranchised LGBTQ+ individuals) are less likely to report corruption. This isparticularly true for sextortion, due to a pervasive culture of victim-blaming and the fear of stigmatisation. This situation is rooted in women’s more limited political and economic agency and their lower levels of literacy and education (Chêne and Fagan, 2013). These are reported to be major barriers to exerting their right to information (Neuman 2016) and to access justice. Gender biases in its effective enforcement are also believed to undermine the potential of the right to information in tackling corruption (Lindstedt and Naurin 2010). Therefore, state institutions, with the support of relevant CSOs, need to ensure the easy accessibility and public availability of gender-sensitive information on reporting mechanisms and legal rights.

They should:

- Integrate a gender perspective to the accessibility and publication of government information. This includes publishing gender-sensitive information in several languages, as well as through easily understandable visualisations. This should overcome language barriers and enable illiterate people to understand the circumstances and effects of corruption, as well as where to report it.

- Design and implement communication, awareness-raising and education strategies, as well as campaigns on the gendered impact of corruption and gender-specific forms of corruption, not only for policymakers, but also for civil society. Special attention should thereby be paid to women belonging to especially disadvantaged groups or minorities, as well as individuals with diverse gender identities or sexual orientation. The aim of this is to ensure that they know their rights and how to exercise them, thus empowering them to report abuse. Moreover, a smart mix of high-tech and low-tech solutions should be used, considering different levels of digital literacy and access to IT in lowand middle-income countries.

- On a legislative level and based on good practices developed in the field (see box headed “Gender and Access to Information”), governments should review existing right-to-information laws to mainstream gender provisions in terms of awareness-raising, accessibility, reporting mechanisms and data collection about the actual use of such legislation. This would effectively target vulnerable groups’ limited knowledge of their rights, while further enshrining the principle of publicly accessible, transparent information.

INCREASING WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION IN PUBLIC LIFE AND IN ANTI-CORRUPTION DECISION-MAKING

The agenda of bringing more women into power positions as an anti-corruption measure in itself will not tackle the issue of corruption in a transformative way and may even perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes (Hossain et al., 2015). Increasing the participation of women should not be regarded as an anti-corruption strategy, but as a fundamental right. Women are often dependent on policies designed mostly by men to address their specific needs. Generally, increased diversity and representation of different social groups will help in reducing long-established, male-dominated networks and generate more insight for a larger segment of the population, which should encourage governments to:

ENHANCE MULTISTAKEHOLDER COOPERATION WITH CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS (CSOS)

CSOs and, more specifically, women’s grassroots organisations, as well as LGBTQ+ organisations, play a crucial role in mobilising resources to voice the needs and interests of disadvantaged groups due to the perpetuation of strict gender norms. CSOs have often been the driving force in the implementation of reforms regarding gendered types of corruption. For example, the Fundación Mujeres en Igualdad managed to foster transparency in various Argentinian regions by obtaining in-depth information about human trafficking at municipality level (Hossain et al. 2015). This initiative proves how crucial the creation of a participatory horizontal framework for collaboration between CSOs and governments is to advancing the policy response to corruption.

Therefore, state institutions shall:

- Enhance social audits in collaboration with local and regional authorities, thereby enabling citizens or CSOs to review public sector expenditure. This has proven to effectively reduce corruption (EUROsociAL+ 2018). Here, the main innovation would be to allow women CSOs fighting against corruption to review public sector expenditure on anti-corruption plans, with a special focus on auditing areas of corruption from which women suffer most (e.g. public services, such as education and health). The co-design of recommendations between relevant authorities and CSOs could enhance more effective corruption monitoring and improve policy formulation at regional or national level.

- Encourage the creation of formal or informal intersectional and multi-stakeholder working groups, as well as networks that will specifically engage with the relationship between gender and corruption, through the aggregation of data, thedevelopment of policy recommendations and the creation of a participatory environment for women to engage in analysing, preventing and penalising corruption. These networks should involve regional and national authorities in a horizontal way to contribute to the discussion along CSOs. Moreover, these networks should follow an intersectional approach, linking the complex relationship of gender and corruption to social background, ethnicity, age and disabilities, among others, but also to LGBTQ+ rights. In the case of LGBTQ+ individuals, it is crucial for CSOs to take part in reporting the problem of sextortion at country level (Goetz et al. 2008).

In Peru, the CSO Proética works towards conducting research via data collection to obtain a more accurate picture of the impacts of corruption on women at national level. This data is then used in campaigns through civil society mobilisation (Transparency International, 2019). https://www.proetica.org.pe/

SAFE REPORTING CHANNELS AND COMPLAINTS MECHANISMS

Vulnerable groups, including women and LGBTQ+ individuals, tend to under-report corruption cases (Transparency International 2017). Apart from the reasons mentioned above, this is also due to the lack of available reporting channels, as well as their inappropriate design (Rheinbay and Chêne, 2016). For example, women may be reluctant to complain to males in some contexts or find male-dominated environments unsupportive (Chêne 2013). Therefore, it is necessary to create reliable and confidential reporting mechanisms that enable individuals to report all types of corruption in a culturally sensitive and context-specific way. The reporting mechanisms should be closely linked to the awareness-raising mechanisms recommended before.

To do so, governments shall:

- Support the development and implementation of reporting mechanisms for corruption and ensure their transparency, independence, accountability, accessibility, safety and cultural and gender sensitivity.

- Follow the approach of Transparency International´s Anti-Corruption Advocacy and Legal Advice Center (ALAC) to the gendered impacts of corruption. It operates in 60 countries worldwide. ALAC provides all citizens with a safe and accessible (online, in person and by phone) reporting mechanism, while providing confidential legal advice and support for citizens to know their rights and assert them (Transparency International, n.d.). To adapt it, specific channels could be opened for sectors such as public services or special forms of gender-based corruption, such as sextortion. This would provide gender-specific support and advice to women reporting corruption cases through e.g., women reporting to female legal experts.

- LGBTQ+ persons often do not report corruption cases due to fear of persecution because their identity is left unrecognised in many countries and they are denied their basic rights. Thus, safe reporting channels should be established to support individuals of diverse bodily characteristics or sexual orientation and diverse or plural gender identities in their reporting process.

REFERENCES

Azcona G., A. Bhatt, J. Encarnacion, J. Plazaola-Castaño, P. Seck, S. Staab, and L. Turquet, From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women, 2020 https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5142

Chêne M. and C. Fagan, “Gender, equality and corruption: What are the linkages?”, Transparency International, Policy Brief 1, 2014 https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/policy-position-01-2014-gender-equality-and-corruption-what-arethe-linkage

Chêne M., “Good practice in community complaints mechanisms”, Transparency International, 2013 https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/helpdesk/good-practices-in-community-complaints-mechanisms

Dollar D., R. Fisman, and R. Gatti, Are Women Really the Fairer Sex? Corruption and Women in Government, World Bank Working Paper Series no. 4, 2001 https://www.agora-parl.org/sites/default/files/agora-documents/gender_and_corruption_0.pdf

EUROsociAL+, ONU Mujeres, C20 Argenti na, Transparency International, Recomendaciones noticia género y ARG_EN, 2018 https://www.eurosocial.eu/files/2018-05/2018_04_02_RECOMENDACIONES_noticia%20genero%20y%20corrupcion_ARG_es_EN.pdf

Feigenblatt H., “Breaking the silence around sextortion: The links between power, sex and corruption”, Transparency International, 2020 https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2020_Report_BreakingSilenceAroundSextortion_English.pdf

Ferreira D., G. Berthin, N. Bernabeu, S. Liborio, M.A. Velasco Rodriguez, and V. Cid, Gender and corruption in Latin America: Is there a Link?, New York, UN Development Programme (UNDP), 2014

Forest M., “Derecho de Acceso a la Información e Igualdad de Género. Una reflexión desde Europa”, HERRAMIENTAS EUROSOCIAL, no. 13, 2019 https://eurosocial.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Herramientas_13.pdf

Fuentes Téllez A., The Link Between Corruption and Gender Inequality: A Heavy Burden for Development and Democracy, Wilson Center, 2018 https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/the-link-between-corruption-and-gender-inequality-heavy-burden-for-development-and

Goetz A.M., H. Cueva-Beteta, R. Eddon, J. Sandler, and M. Doraid, Progress of the world’s women 2008/2009 – Who answers women, UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), 2008 https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2008/1/progress-of-the-world-s-women-2008-2009-who-answers-to-women

Goetz A.M., “Political cleaners: Women as the new anti-corruption force?”, Development and Change, vol. 38, no. 1, 2007, pp. 87-105

He S., “Fairer Sex or Fairer System? Gender and Corruption Revisited”, Social Forces, vol. 82, no. 2, 2003 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i278742

Hossain N., C.N. Musembi, and J. Hughes, Corruption, Accountability and Gender: Understanding the Connections, UN Development Programme (UNDP) and UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), 17 December 2015 https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Corruption-accountability-and-gender.pdf

Lindstedt C. and D. Naurin, “Transparency is not Enough: Making Transparency Effective in Reducing Corruption”, Political Science Review, vol 31, no. 3, 2010, pp. 301-22 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258142264_Transparency_Is_Not_Enough_Making_Transparency_Effective_in_Reducing_Corruption

National Sexual Violence Resource Center, Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, Sexual Violence & People who identify as LGBTQ, Research Brief, 2012

Neuman L., “The Right of Access to Information: Exploring Gender Inequities”, Institute of Development Studies, IDSBulletin, vol. 47, no. 1, 2016, pp. 83-98 https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/38/html

Rheinbay J. and M. Chêne, Gender and corruption topic guide. Compiled by the Anti-Corruption Helpdesk, Berlin

Transparency International, 2016 https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/topic-guides/Topic-guide-gender-corruption-Final-2016.pdf

Sánchez-Páramo C. and A.M. Munoz-Boudet, “No, 70% of the world’s poor aren’t women, but that doesn’t mean poverty isn’t sexist”, World Bank Blogs, 8 March 2018 https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/no-70-world-s-poor-aren-t-women-doesn-t-mean-poverty-isn-t-sexist

Swami A., O. Azfar, and S. Knack, Gender and Corruption, IRIS Centre Working Paper no. 232, 2000 https://web.williams.edu/Economics/wp/Swamy_gender.pdf

Transparency and Legal Advice Services (ALACs)” (n.d.) https://www.transparency.org/en/alacs

Transparency International, “Global Corruption Barometer results”, Results for Africa, 2017 https://www.transparency.org/en/gcb/global/global-corruption-barometer-2017

Transparency International, “What is Grand Corruption and how can we stop it?”, 21 September 2016 https://www.transparency.org/en/news/what-is-grand-corruption-and-how-can-we-stop-it

Transparency International, “Women and corruption in Latin America & the Caribbean”, 23 September 2019 https://www.transparency.org/en/news/women-and-corruption-GCB

UN Development Programme (UNDP), Seeing beyond the state: Grassroots women’s perspectives on corruption and anti-corruption, New York, UNDP and Huairou Commission, October 2012 https://www.undp.org/publications/seeing-beyond-state-grassroots-womens-perspectives-corruption-and-anti-corruption

UN Women and Transparency International, End gendered corruption in Latin America and The Caribbean with coordinated action, September 2019 https://lac.unwomen.org/en/noticias-y-eventos/articulos/2019/09/press-release—el-impacto-de-la-corrupcion-en-las-mujeres

UNODC, Mainstreaming gender in corruption projects/programmes, Gender Brief for UNODC Staff, (n.d.) https://www.unodc.org/documents/Gender/Thematic_Gender_Briefs_English/Corruption_brief_23_03_2020.pdf

United Nations (UN), “Corruption Defined”, in UN, Handbook on Practical Anti-Corruption Measures for Prosecutors and Investigators, September 2004, p. 23-30 https://www.unodc.org/pdf/corruption/publications_handbook_prosecutors.pdf

Vivi A., L. Cameron, A. Chaudhuri, N. Erkal, and L. Gangadharan, “Gender, Culture, and Corruption: Insights from an Experimental Analysis”, Southern Economic Journal, vol. 75, no. 3, 2009, pp. 663-80 https://www.jstor.org/stable/i27751404

World Bank, Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune, 2020 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34496/9781464816024.pdf