Official development assistance (ODA) is critical for closing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) funding gap because its use in blended finance schemes can crowd in other sources of funding. First, a global currency transaction tax (CTT) of 0.005 percent should be imposed to raise US$72 billion in revenue. Second, all Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members should adopt the ODA/gross national income (GNI) differentiated target setting scheme. Third, the DAC should co-opt eight high-income and upper-middle-income G20 countries currently not in the DAC, into the committee. Besides closing the SDG financing gap faced by developing countries, these three recommendations will strengthen the solidarity between rich G20 nations and emerging strong G20 nations to achieve the 17 SDGs.

Challenge

In 1970, the United Nations adopted a resolution that developed countries adopt an ODA target of 0.7 percent of donor GNI to help the developing countries to grow faster (UN, 1970). However, the ODA has averaged at only 0.3 percent of donor GNI in the last decade before 2020. The actual ODA was $161 billion in 2020 versus the target ODA of $349 billion, a shortfall of $188 billion.

ODA plays an important catalytic role in the overall financing to help achieve sustainable development globally. ODA emphasises concessionary funding (since 2018 all ODA is calculated in grant equivalents to recognise the effort of donor countries who provide official aid financing with high levels of subsidies) that can be used in blended finance to crowd-in other sources of financing, in particular environmental, social and government (ESG) guided investment funds and other commercial funds.

These ODA shortfalls have contributed to the widening of the income gap between the poor and rich nations. In 1970, the gross domestic product per capita of the least developed countries (LDCs) was 4.5 percent of that of the developed countries. By 2020, this ratio had fallen significantly to 3 percent. In order to achieve the 17 SDGs that were adopted by the UN in 2015 to give every human on the planet a decent living through access to health, education and basic infrastructure, it is absolutely critical that ODA commitments made by rich countries are achieved and the SDG financing gap is closed.

Proposal

According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the 140 developing countries face an annual SDG financing gap of $2,500 billion in the 2015-2030 period (UNCTAD, 2014). For the 59 low-income developing countries as classified by the International Monetary Fund, Sachs et al. (2018) found an annual SDG funding gap of $400 billion from 2019-2030. Therefore, developing countries, especially the LDCs, desperately need concessionary international financial assistance such as ODA if we are to collectively achieve the SDGs of the 2030 Agenda. This paper focuses on how to raise ODA to close the SDG funding gap in three steps.

The first step is to quickly raise ODA contributions by implementing a worldwide Currency Transactions Tax (CTT). The global currency market is the largest financial market in the world with an annual turnover of around $798 trillion in 2007 and $1,715 trillion in 2019 (BIS, 2019). According to Schmidt (2008), a CTT of 0.005 percent (0.5 bps)[1] would cause a reduction in currency transaction volumes of 14 percent. Based on these parameters, a CTT in 2007 would have raised around $33 billion from major currencies in the world (i.e. $, €, £ and ¥). As annual turnover in the forex markets has increased by 115 percent between 2007 and 2019, a CTT of 0.005 percent – assuming all other behavior remains the same – would raise $72 billion in 2019.

The expected revenue raised of $72 billion can be used to quickly narrow the ODA shortfall of $188 billion. We propose for the ODA funding raised to be attributed based on the place of domicile of developed countries’ citizens and corporate headquarters. For example, CTT raised from JP Morgan globally, will be attributed to the US’ ODA because JP Morgan is a US-headquartered bank. As developing countries do not contribute to the ODA, CTT raised from citizens and corporate headquarters domiciled in developing countries will be withheld and earmarked for SDG projects in its own jurisdiction.

The CTT has advantages over the EU Financial Transaction Tax (EU FTT) first proposed in 2011, which applies a tax on a wide set of financial asset classes (e.g. stocks, bonds, derivatives) transacted in EU member states. There are two reasons why the EU FTT has not been able to secure broad political support. First, the EU FTT was proposed to be applied only in the EU. Therefore, EU member states like the United Kingdom and Sweden opposed the EU FTT for fear that it would erode the competitiveness of their financial sector. We propose a worldwide CTT that will be applied globally, hence the issue of creating an uneven competitive environment does not arise. Second, the EU FTT applies a tax on a wide set of financial asset classes, therefore some EU member states opposed it as it conflicted with local financial priorities. For example, Italy opposed the EU FTT because government bonds were proposed to be taxed, while the Netherlands opposed it because pension funds were proposed to be taxed. The proposed CTT will apply to only one financial instrument (i.e., currencies). Therefore, member states are less likely to object because potential conflicts with local financial priorities are significantly reduced.

Finally, the CTT can be implemented globally because all currency transactions worldwide are recorded at the gross level using the SWIFT messaging system. Furthermore, the execution of the 0.005 percent CTT can be implemented automatically and electronically because all foreign exchange settlement systems, whether on-shore or off-shore, require an account with the central bank that issues the currency. Moreover, the Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) Bank, launched in 2002, now settles more than half of all foreign exchange transactions with the remainder being processed by the central bank’s national real-time gross settlements (RTGS). Both of these systems allow a one-to-one correspondence between foreign exchange payments and their originating trades (i.e. payment for payment) (McCulloch and Pacillo, 2011). Hence, the entire global CTT can be implemented under the coordination of central banks around the world, CLS and SWIFT. Therefore, we recommend that the central banks in the G20 commit to developing an implementation plan for a worldwide CTT together with CLS and SWIFT, which can be endorsed for implementation by the Leaders at the G20 in India in 2023.

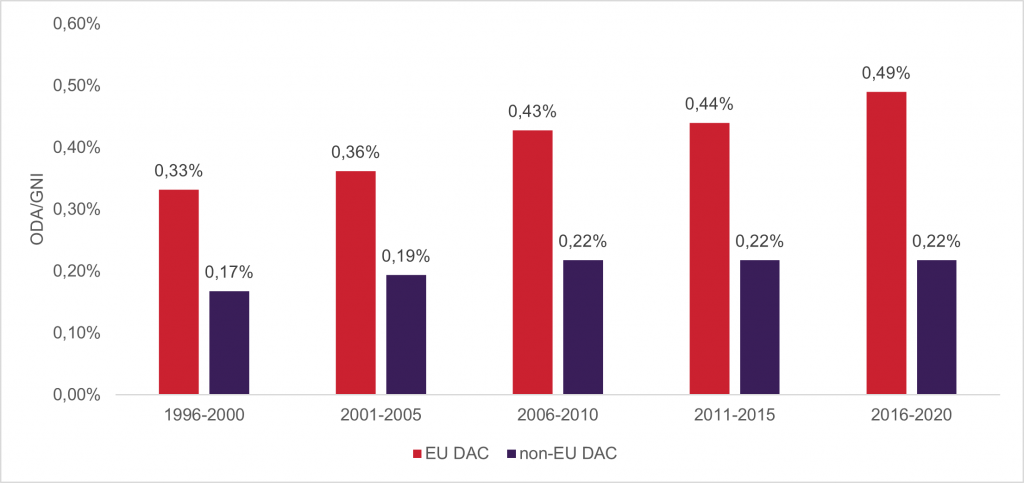

The first step would raise around $72 billion, which can be used to quickly narrow the ODA shortfall, but this will not be sufficient to achieve the aspired ODA target of 0.7 percent of GNI. Therefore, a second step to raise the ODA is required over the longer term, which is to put in place the institutional arrangements to set ODA targets in a differentiated manner and monitor the delivery of funds against the targets. This intervention was implemented by the EU in 2002 and was observed to enable the EU to outperform non-EU DAC countries in delivering their ODA commitments over the past two decades. From Figure 1, it can be observed that ODA contributions by EU countries measured by ODA/GNI have increased by 0.16 percent from 1996-2000 to 2016-2020, while ODA/GNI of non-EU DAC countries (predominantly the US, Japan, Canada) increased only by 0.05 percent over the same period (European Council, 2021).

Figure 1: Average ODA/GNI for EU and non-EU DAC countries over the past two decades

The EU’s willingness to contribute a larger share of its national income to the ODA could be attributed to the EU’s institutional arrangements to set ODA targets in a differentiated manner and monitor the delivery of funds against the targets. In 2002, the European Council meeting in Barcelona affirmed that EU member states should reach the 0.7 percent target (European Council, 2002). In 2015, to reflect actual funding performance and commitment to the 2030 Agenda, the EU affirmed its commitment to achieving the 0.7 percent target by 2030. For member states which joined the EU after 2002, they commit to a target of 0.33 percent. To further take into consideration LDCs who are falling further behind in achieving the SDGs, the EU member states collectively target 0.15-0.2 percent of ODA/GNI in the short term and 0.2 percent by 2030 (European Council, 2015). To govern the performance of member states against targets, each member’s performance has been presented to the European Council annually since 2010 (European Council, 2021).

Recognising the effectiveness of the institutional arrangements made by the EU to create a conducive reporting and governance environment to encourage an increase in ODA/GNI contributions, we urge the G20 leaders to request the OECD Secretariat and the DAC to put in place similar institutional arrangements for all DAC members (Full list of DAC members is presented in Appendix 1). All DAC members are requested to have a target of 0.7 percent by 2030, and give priority to LDCs by setting a sub-target of 0.2 percent for LDCs by 2030. Consistent with the EU commitments and the principle of joint but differentiated responsibility, EU member states that joined the EU after 2002 (Hungary, Slovenia, Poland, Slovak Republic, Czech Republic), commit to a target of 0.33 percent.

Assuming that all DAC members achieve the 0.7 percent ODA/GNI target, annual DAC flows will reach around $349 billion. This is still short of the annual $400 billion needed by low-income developing countries to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Therefore, as the third step to close this gap, we propose that the DAC coopt eight high-income and upper-middle-income[2] G20 countries currently not in the DAC, namely Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Turkey, into the DAC. Consistent with the EU, newly coopted DAC members would be allowed to set targets along the principle of joint but differentiated responsibility. As an immediate practical next step to facilitate the cooption of high-income and upper-middle-income G20 countries not in the DAC into the DAC and to encourage all G20 countries not in the DAC (this would include G20 countries that have not reached and surpassed the upper-middle-income threshold like India and Indonesia) to voluntarily adopt a grant equivalent method to account for official aid financing, we propose for the OECD Secretariat and the OECD Development Center to conduct capacity building for all non-DAC G20 countries on an ODA grant equivalent reporting method.

The advantages of the third proposal are threefold. First, in 2020 the combined GNI of the eight high-income and upper-middle-income G20 countries currently not in the DAC was around $20 trillion. Assuming the joint but differentiated responsibility principle, and an ODA/GNI target of 0.33 percent is applied, this would raise around $69 billion of additional ODA funding, thus increasing the total ODA funding to over $400 billion, enabling the SDG financing gap to low income developing countries to be closed. With enough crowding-in effects through blended finance instruments, the $2.5 trillion SDG funding gap for all developing countries could also be closed. Second, this third step facilitates an increasing amount of development aid funded by non-DAC members to be accounted for under the DAC grant equivalent method, to recognise official aid financing that has a high level of subsidy. Finally, this third step creates global solidarity within the G20 and amongst stakeholders across the world to achieve the SDGs, leaving no one behind and protecting our planet for future generations. This is because rich countries and blocs like the US and the EU, and strong emerging G20 countries like China and Russia are invited to work together to channel the necessary resources and design effective aid interventions under the DAC framework to achieve the global aspiration of the SDGs by 2030.

References

BIS. Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019, Bank for International Settlements, Basle, 2019

European Council, Barcelona European Council, Presidency Conclusions, 15-16 March 2002, para 13 page 5, https://ec.europa.eu/invest-in-research/pdf/download_en/barcelona_european_council.pdf

European Council, A New Global Partnership for Poverty Eradication and Sustainable Development after 2015, 9241/15, 26 May 2015, para 32-34 page 11-12, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9241-2015-INIT/en/pdf

European Council, Annual Report 2021 to the European Council on the EU Development Aid Targets, 9549/21, 14 June 2021, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9549-2021-INIT/en/pdf

European Union Financial Transaction Tax, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_financial_transaction_tax

McCulloch, N. and Pacillo, G., 2011. The Tobin tax: a review of the evidence. IDS Research Reports, 2011

Schmidt R., The Currency Transaction Tax: Rate and Revenue Estimates, Hong Kong: United Nations University Press, 2008

World Bank, World Development Indicators 2022. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

UN General Assembly, Resolution on International Development Strategy for the Second United Nations Development Decade, (R2626 (XXV)), 24 October 1970, para. 43, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/348/91/IMG/NR034891.pdf?OpenElement

UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2014: Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan. United Nations Publication, New York and Geneva, 2014

UNCTAD, UNCTADStat, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx

Appendix

Appendix 1: List of 30 DAC countries and their ODA as a percentage of GNI in 2020

| Country | ODA/GNI in 2020 (%) |

| Sweden | 1.139 |

| Norway | 1.109 |

| Luxembourg | 1.025 |

| Denmark | 0.730 |

| Germany | 0.727 |

| United Kingdom | 0.698 |

| Netherlands | 0.592 |

| France | 0.532 |

| Switzerland | 0.482 |

| Finland | 0.468 |

| Belgium | 0.467 |

| Canada | 0.310 |

| Japan | 0.310 |

| Ireland | 0.306 |

| Austria | 0.296 |

| New Zealand | 0.270 |

| Iceland | 0.269 |

| Hungary | 0.267 |

| Spain | 0.235 |

| Italy | 0.220 |

| Australia | 0.191 |

| Greece | 0.176 |

| Slovenia | 0.172 |

| Portugal | 0.171 |

| United States | 0.165 |

| Poland | 0.139 |

| Slovak Republic | 0.137 |

| Republic of Korea | 0.137 |

| Czech Republic | 0.130 |

- It should be noted that the one-way average spread (i.e. bid and mid-point; mid-point and ask) for the $ with other major currencies (i.e. €, £ and ¥) is around 0.015 percent, therefore the CTT will result in a post-tax one-way spread of 0.020 percent. ↑

- Classified according to the World Bank for 2020, consistent with DAC’s approach in classifying countries for the 2022 and 2023 ODA flows period. ↑